This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

In an issue devoted to stories of censorship and other acts of cowardice and things hidden, I want to add a story about courage in the face of art.

I’ve been making part of my living as a sort of playwright-for-hire, creating performance pieces out of oral histories for communities. The pieces begin as humanities projects or economic development projects or projects undertaken because somebody needs people to talk cooperatively with one another, and this looks like a good way to get them started.

What I create are not plays in the traditional sense. They are more like patchwork quilts of stories which community people, not professional actors, play back for the community in public performances. Room is made for whoever wants to participate. That is often stage-struck children. Sometimes people have to be begged to participate, usually adults who already have plenty to do.

The process begins with whoever can be roped into using a tape recorder and going to their relatives and neighbors to collect oral histories. This may be the most important part because people have to listen to each other.

As a writer of performance pieces, I am not looking for the same things historians want when they gather oral histories. I need stories of things that have happened to people, and I want the best raconteurs on tape, not necessarily the folks with the most accurate memories. Sometimes they are the same people but not always, and in truth, not often.

My nightmare in this process is when oral history takers are given a list of questions to follow. The last project of that nature had about 1000 pages of oral histories from 75 or so people with two stories — count them, two — in the whole collection. All the rest was answers to questions designed to gather opinions, not stories. It is very hard to write a play out of opinion.

The collected oral histories are transcribed, and the transcriptions come to me. I choose stories I can make some kind of whole with. I don’t always follow a single story line through the play, though I have done that. I might follow a theme — the work of a place, for example. An emotional path can be the organizational backbone, or a character I keep coming back to. The structure varies every time I do a new piece. I also play loose and free as a writer with the stuff in the oral histories. I’m not inclined to ruin a good story by sticking to facts; truth is, most people seem to like it when I add some salt to the meat.

My main job as a writer is giving these past tense narrative stories some dramatic value so they become interesting on-stage. I use every trick I know or can think up, then I carry the script back to the community, and we produce it. I am currently working on my 10th show with two more to come in the next six months. I’m doing women’s stories in East Tennessee (the Hidden Heroines project) and single room occupancy hotel stories for Scrap Metal project in Chicago.

And so we come to Colquitt and to courage.

The most successful of these endeavors is an economic development project called Swamp Gravy in the town of Colquitt, Georgia.

Swamp Gravy is named after a dish made with whatever is on hand — tomatoes, peppers, onions, rice — to accompany fried fish. Colquitt is a small town (about 3,000) in the piney woods of southwest Georgia. The economy is agricultural — cotton, soybeans, and peanuts, and if you’re not farming, you are doing something related. There is not much else to do. You can buy all the brides’ magazines a human could want, and the current House Beautiful and Southern Living at the grocery store in Colquitt, but it is 20 miles to a Kmart and a Newsweek or an Atlantic. A good bit further — 120 miles — to a Mother Jones or a Southern Exposure. There is a video rental store, but the closest movie house is also a drive away. Swamp Gravy is literally the only show in town. It runs 30 to 40 nights a year downtown in a renovated old cotton warehouse that seats about 200 but has room for another hundred standing. Swamp Gravy often plays to 300 people per night.

These folks are currently collecting oral histories for their sixth show. We keep changing the show in Colquitt because most of the Swamp Gravy audience comes once or twice a year to see it, and we try to give them something that is (in part) new once a year.

Swamp Gravy was part of the Cultural Olympiad (a rather exclusive list of recommended cultural events in the South to see while in the country for the Olympics) and about the time this issue of Southern Exposure gets to your mailbox, Swamp Gravy will play an invitational evening at the Kennedy Center in Washington. They’ve made national media several times, and Jimmy and Rosalyn Carter came to see the play last summer. Sometimes all this seems almost like magic, but it has been hard, politically savvy work by the folks in Colquitt.

I am the hired playwright, and worse, I am imported, i.e., I am not from Colquitt. This is not fashionable in the politics of art these days. Communities are supposed to grow their own. Using an imported artist is a little like using nondairy creamer or instant coffee: it will do, but only if you don’t have the real thing, and everyone will wonder about your upbringing. Not being from Colquitt made me suspect there, too. A person actually asked me why on earth would I want to come to Colquitt if I wasn’t trying to rip them off. My first trip there, I wondered the same thing. Our relations have improved. Five plays and five years later, I’ve earned a measure of trust, and nobody local is clamoring to take over the playwright’s job. So, suspect though I still am, it is for being an artist at all, and not for being from somewhere else. I live with this suspect artist stuff in my neighborhood at home.

We had done two or three shows, I forget which, when the story I want to tell comes up. The early oral histories were bland — people had no notion of what we were trying to do with their stories and no faith that we would do them any sort of justice. As the community liked what we did, collecting stories got a little easier, and then, almost like a dare, there came a hard story from a woman who had shot and killed her abusive husband after 14 years of being married to him. I felt we had to honor it somehow. It represented a new level of trust from that community. We’d done something right, or that story would not have been told for our ears, so I wrote it up.

The first responses were predictable: “We can’t do that story. It’s too awful.” “We can’t say anything bad about Colquitt. People won’t like it. They won’t come back.” “We cannot tell a story like this in public.” What you can and should read is, “I’m scared of whatever level of opprobrium this brings down on my head.”

It was not an ungrounded fear. It would have been left there, the piece omitted from the play, but for a cast member who stood up in rehearsal and said, “This sort of thing does happen here. This story came in the oral histories. We should at least try it.” So try it they did. Sure enough, they got some letters of protest from the churches in town about including this material in a “family show,” and a few of their audience protested and swore they wouldn’t come back, but what I think of as the brown dress story is now one of the strongest and most requested stories in the Swamp Gravy collection. They used it last year to raise money ($23,000) for a women’s center in Albany, Georgia.

If you are thinking, “But this is such old hat, wife abuse, the women-in-jeopardy made-for-TV movies,” if you are thinking something like that, you do not know how hard it can be to tell real stories, out loud in front of real people in places where the tradition of silence in such matters is so very, very strong.

We did not want this story to point to any particular ethnic or racial community so the director of Swamp Gravy, Dr. Richard Geer, gave it to a black woman and a white woman to tell at the same time. It was a good idea. So, this is one story, but it has two tellers.

The Brown Dress

(An officer is taking notes, a deposition.)

BOTH: He bought me a brown dress

WOMAN ONE: It was a house dress kind of thing,

WOMAN TWO: cheap and flimsy and too big for me, and it was my Easter dress.

WOMAN ONE: He dressed like a peacock,

WOMAN TWO: hundred dollar suits, and good shirts and shoes. He wore

WOMAN ONE: three shirts a day, and he wanted them blue-white,

WOMAN TWO: starched and ironed,

WOMAN ONE: and I spent my Saturdays on them,

WOMAN TWO: twenty-one a week. Not to mention mine and the children’s clothes. I was washing shirts

WOMAN ONE: when he come in with this dress.

WOMAN TWO: I wouldn’t have worn it to teach school.

WOMAN ONE: I didn’t.

WOMAN TWO: It is still hanging in my closet.

WOMAN ONE: I wore it once.

BOTH: Easter Sunday.

WOMAN TWO: But I didn’t say a word about it. I was supposed to be

WOMAN ONE: thankful for it.

WOMAN TWO: He told me I

WOMAN ONE: better act thankful for it

BOTH: even if I wasn’t.

WOMAN ONE: (Slowly) Looking at it made me cry, not just the dress, but the threat of it. And his sisters

WOMAN TWO: out prowling the road for footprints

WOMAN ONE: to see if I’d walked anywhere when he wasn’t there. Every day,

WOMAN TWO: they’d get out on the road and look and see if my footprints were there.

WOMAN ONE: Sometimes they were. We had a car,

WOMAN TWO: but if me and the children weren’t ready when he thought we ought to be, WOMAN ONE: he’d drive away and leave us

BOTH: and there was hell to pay

WOMAN TWO: if we weren’t there on time.

BOTH: He and I worked in the same place,

WOMAN ONE: and the children went to school there.

BOTH: We went to the same church,

WOMAN TWO: but I can’t tell you how often we walked and he didn’t.

WOMAN ONE: And them sisters, they’d say,

WOMAN TWO: “She’s been out

WOMAN ONE: “she’s been out

WOMAN TWO: “she’s been out.

BOTH: walking, brother.”

WOMAN ONE: And then, he’d want to know where I’d been.

WOMAN TWO: To church. On Easter Sunday

BOTH: in a trashy brown dress.

WOMAN ONE: So it wasn’t just the dress.

OFFICER: Get to the night in question, please.

WOMAN ONE: There are 14 years of nights in question,

WOMAN TWO: almost all in which he did something to me or the children,

WOMAN ONE: and one

WOMAN TWO: in which I did something

WOMAN ONE: to him. Now, I know what you’re wanting me to say, and I’m getting to it, but I’m not going to say it without saying some of this other stuff first, and what I really want to know is why you’ve not been here before now.

WOMAN TWO: Cause I’m black, and what happens in this neighborhood is not something you worry much about? ’Cause this time it is a man been hit

WOMAN ONE: and not a woman?

OFFICER: I got a call, ma’am.

WOMAN ONE: I know you did. I’m the one that called you. I don’t care if you don’t write down about the brown dress, but write this down.

BOTH: He beat us, all of us.

WOMAN ONE: His sisters saw that, too, but they didn’t worry about that.

WOMAN TWO: They were here,

BOTH: both of them,

WOMAN ONE: the nights all three of my children were born, and they’d look at those babies when they came out of my body and try to decide whether or not they looked like him.

WOMAN TWO: They were his,

BOTH: all of them. (Pause) He beat me the night the third one was born because they didn’t think she looked like him. And he beat her. Not that night, but as she grew. She’s nine years old, and she has scars all over her back where her clothes cover them and you can’t see them.

WOMAN ONE: He was careful about that. I’ve got scars

WOMAN TWO: on my back, too.

BOTH: We all do. And then he takes a deacon’s job in church. And he’s principal at the school. WOMAN ONE: A fine man,

WOMAN TWO: a real role model for his community. He beat

WOMAN ONE: everything that could be hurt by beating

WOMAN TWO: except those sisters of his.

WOMAN ONE: Now, did you write that down?

OFFICER: Victim allegedly beat wife and children. (Woman One jerks the tail of her blouse from her skirt and holds it up to show the man her back.)

OFFICER: Jesus, woman, looks like you’ve been worked over with a bullwhip.

WOMAN ONE: I have been. Victim BEAT his wife and children. Mark out allegedly.

OFFICER: It’s just legal language. (Woman One dresses)

WOMAN TWO: Mark it out.

OFFICER: It’s out. (He writes something else.)

WOMAN TWO: He kept a gun in his coat pocket.

WOMAN ONE: Loaded.

WOMAN TWO: A .38.

WOMAN ONE: And a shotgun in the house.

WOMAN TWO: Also loaded. And he came in, he took his coat off —

WOMAN ONE: it was hot —

WOMAN TWO: and for no reason I know — he hauled the youngest into our room. I could hear her screaming.

WOMAN ONE: And I don’t know why it was this day and not some time before, but I said to myself, “enough is enough”

WOMAN TWO: Enough is enough. I didn’t see his coat, I figured he still had the .38 in his pocket,

WOMAN ONE: I figured.

WOMAN TWO: and I thought I might die, but I’ve thought that before, and I didn’t. I walked into our room,

WOMAN ONE: I figured

WOMAN TWO: and pointed the shotgun at him and told him to

WOMAN ONE: quit!

WOMAN TWO: or I’d shoot him,

WOMAN ONE: and he came after me.

WOMAN TWO: He felt his pockets for the gun,

WOMAN ONE: for the gun

WOMAN TWO: and I ran into the yard. I was yelling for help when he came out the door . . . WOMAN ONE: (Softly, intensely, fast) I don’t care if you don’t write down about the brown dress, but write this down. He beat us, all of us. His sisters saw that, too, but they didn’t worry about that. They were here, both of them, the nights all three of my children were born, and they’d look at those babies when they came out of my body and try to decide whether or not they looked like him. They were his, all of them. He beat me the night the third one was born because they didn’t think she looked like him. And he beat her. Not that night, but as she grew. She’s nine years old, and she has scars all over her back, scars all over her back, scars all over her back.

WOMAN TWO: (Precisely and slowly) And he had his coat in his hand and he was reaching for the gun in the pocket of it, and I pointed the shotgun at him and pulled the trigger,

BOTH: and he fell on the porch and died.

WOMAN TWO: I killed him.

WOMAN ONE: There are the words you’re looking for. Write them down.

WOMAN TWO: Read me what you’ve written.

WOMAN ONE: I am an English teacher.

OFFICER: Brown dress.

WOMAN TWO: Cross out brown dress.

WOMAN ONE: It is not a complete sentence.

OFFICER: Suspect states victim beat her and the children. Suspect states another beating of youngest child was in process. Suspect states she had reason to believe victim was armed. Suspect states she tried to halt beating. Suspect states she shot victim in self defense.

WOMAN TWO: And that’s it?

WOMAN ONE: That’s all you wrote of what I told you?

OFFICER: That’s what I need.

BOTH: (they turn to each other) But it is not the story.

(Officer exits)

WOMAN TWO: I am not proud of this story,

BOTH: not proud

WOMAN ONE: of what I did,

WOMAN TWO: I did,

WOMAN ONE: but I would do it again tomorrow if I had to,

WOMAN TWO: and my regret,

WOMAN ONE: if I have one,

BOTH: is that I did not do it sooner.

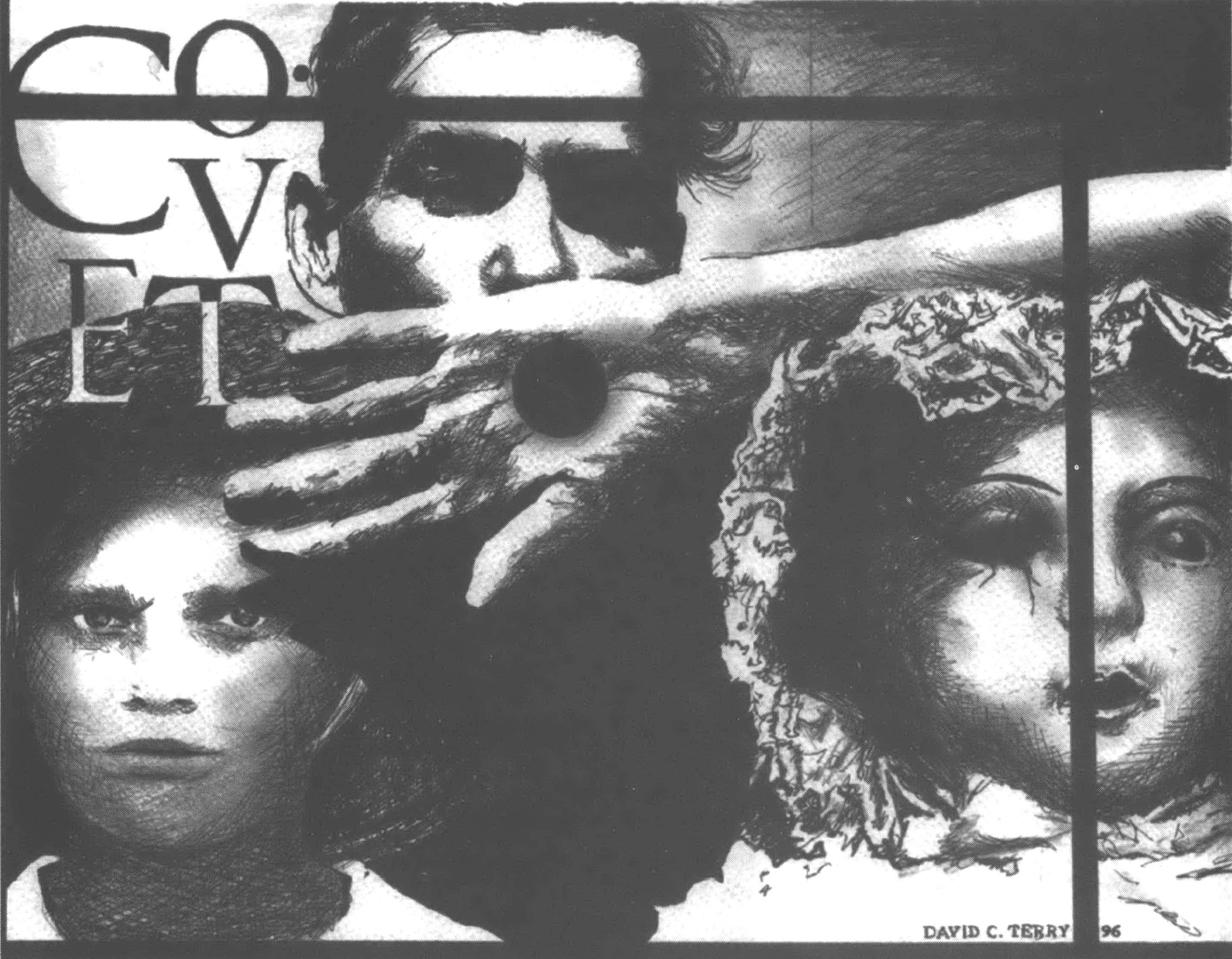

The second piece is similar in how hard it is, but the story shows another fold in community and community involvement: After we did “Brown Dress,” two stories of childhood sexual abuse came in with the new oral histories. They both came in anonymously. They probably came because we had done right by the brown dress story, and I chose one that I could make fit in the new play. That play was called The Gospel Truth — Swampers wanted to do a show about faith, trials of faith, and coming to faith. I was using snatches of a 10 Commandments’ sermon by a locally famous preacher, and coming out of each of the commandments with a story that either kept or broke that commandment. This was the story that broke “Thou Shalt Not Covet.”

I carried the piece in to rehearsal, and I warned people it was hard. There was a long minute of silence after we read it the first time — the sort of silence that is so hard on playwrights’ stomachs — and finally, a cast member said “Jo, you can’t say ‘sex’ and you can’t say ‘breast.’”

“I beg your pardon?”

“You cannot say those words on-stage here. This is a piece we probably have to do like we had to do the brown dress story, but you can’t say ‘breast’ and you can’t say ‘sex.’”

“Well,” I asked, “can I just cut those words?” And that’s literally what we did. It makes the piece even harder in performance, but the courage is in the telling of the story and not in the words used. This piece has a deacon in it, too. I am not trying to pick on deacons, though they do seem to show up a lot. The deacons were unchanged details from the oral histories. I wrote this as if it were an encounter/conversation between a woman and her younger self that takes place at a funeral. Again, in performance, we did not want this to point to anyone in particular, so Director Richard Geer divided it between a number of women, older and younger. It can be played by as few as two or as many as 12. It works best with four, five, or six. It does need the older/ younger division in places.

Covet

— I was five. What can you covet when you are five? Your older sister’s new shoes?

— But you had new shoes, too, new used shoes, shoes she had outgrown, but new to you. And you had no need of fancy shoes, so stop worrying it.

— I had work to do.

— Everybody had work to do.

— I had to carry water to the animals.

— Are you going to pass his house again?

— I carried a bucket at a time, because I was not big enough to carry two buckets,

— and I had to pass by his house to do it.

— And what did he covet?

— I don’t care.

— You do so care, you care very much.

— I’m glad he is dead.

— I know.

— I hate funerals.

— I know.

— I am always back at his funeral, and I am 10 years old, and the minute I am let out of this church, out from behind my mother’s skirt, my mother who doesn’t know anything, I will run like a banshee and scream and play with the others. There is no greater joy for any of us than this death, and this day is our . . .

— Redemption? Do you dare say redemption?

— No, I wish it was, but it isn’t.

— It is just a release,

— No more.

— Is it a sin to be so glad he is dead?

— I can’t help it if it is.

— You have to stand here anyway.

— You all have to stand here. He was a deacon.

— Everybody in the church comes to his funeral.

— So I look at

— Sara,

— Alice,

— Jane

— and Morgan, a girl named Morgan.

— Do they look back?

— No. But they know I’m looking at them,

— And they know I am one of them.

— Each of us knows the other is one of us.

— How would they know?

— They suspect like I suspect, they know like I know.

— We each saw the other coming out of his house.

— It was a shack, it wasn’t a house. You could smell it, the unwashed clothes, unchanged bedding, and too many times he just went in the yard when he was too lazy to get to the outhouse.

— “A good man has fallen on hard times.”

— Daddy said that.

— Daddy didn’t know any better.

— I think sometimes about people who punish themselves somehow really bad because they are sinners.

— Are you one of them?

— I think I am.

— Was he?

— He had money. I mean, he had quarters when he wanted them.

— But he lived in such squalor. Why else, except to punish himself, would he live with such filth?

— What did he covet?

— He would watch me when I passed his house.

— He said.

— “Come here, little girl.”

— No. Don’t say that ever again.

— “Come over here, little girl. I’ve got a present for you.”

— A present.

— I would very much like to have a present.

— So you wanted a present. Your first present was a doll with an eye poked out.

— But that was OK.— I could find a pretty rock to go in the eye hole.

— Except I remember where he said he wanted to touch me before he gave it to me.

— Your (gestures to her breast)?

— I had a child’s body. I was five years old.

— And I prided myself on how fast I could run.

— I had a tooth missing and white chicken fuzz for hair, but he told me I was pretty.

— He wanted to touch a child.

— My second present was a quarter.

— A quarter was an awfully lot of money.

— I had never had a quarter of my own before.

— I coveted the quarter.

— And his hand was not pleasant, but it was a sort of caress, it didn’t hurt . . .

— He hurt Sara. She had to pass his house, too.

— I saw her coming out and she was crying. (as the man) Come here. I’m lonely.

— He gave her quarters, too,

— she wanted the quarters just like I did.

— A quarter was so much money then.

— What did he covet?

— Why do you keep asking that?

— I don’t care.

— He was a pervert. He hurt Jane, too. I don’t know about Alice and Morgan.

— You think you are free because he is dead?

— I want this funeral to be over.

— I want to run like a banshee in the yard with

— Sara

— and Alice

— and Jane

— and Morgan,

— and look at one another in the eyes and know he is not in that house anymore.

— (as the man) Come here. You are so pretty, little girl. So pretty, you have white hair.

— What’s wrong with wanting a quarter?

— My mother never told me a word about . . . anything until after I got my period,

— and when it came, I thought I was wounded, maybe dying, and all she said was it was natural but that

— you mustn’t let any boys touch you.

— but the dispenser of quarters wasn’t a boy.

— And by the time he started doing the things that hurt my body,

— I was guilty, too, guilty of the pleasure of quarters if not of the acts themselves,

— and I didn’t know how to say no anymore.

— (as the man) “Here, girlie, you’re big enough now to climb up here and sit on my lap.”

— Please. Stop it.

— It will be 40 years before you can tell this story even to yourself.

— I want to run like a banshee.

— Forty years before you can stand at anyone’s funeral,

— even someone you love,

— without reliving his.

— I want to look Sara and Alice and Jane and Morgan in the eyes and know he isn’t there,

— Forty years before you begin to wonder what happened to

— Sara

— and Alice

— and Jane

— and Morgan

— and wonder if they ever spoke to anyone, and if they are afraid of funerals.

— I want to look them in the eyes, and know we do not have to fear passing by that house ever again.

— Forty years before you can say to yourself why you were so fearful, so careful, for your own children.

— I want to run.

— I want to go outside and run.

— I am so fast when I run, it is very hard to see me.

— Forty years in the wilderness.

The courage here? Aside from the community doing this story, the woman whose story it is performed in it. What she says of the experience is that she had been afraid of her abuser for 40 years, dead or not, even in her dreams she was afraid, all she had to do was think of him and the fear poured over her again and made her knees weak and her stomach nauseous. Telling the story has taken the power out of him. I tell her it is hers now, that power, or it could be. I say it as a joke, sort of, and she laughs. She does not seem comfortable with the idea of having power at all, but she has changed for telling that story. You can see it in how easily she meets your eyes now with her own, and she is taking back some power from somewhere whether she wants it, or intends it, or not.

Oh, hallelujah. I knew there was heart in this work.

People, communities, whatever living entity it is that wants courage, are changed by finding even a small measure of it, like the capacity to tell real stories out loud. It is what makes arts so wondrous and so very dangerous all in the same breath.

Tags

Jo Carson

Poet, playwright, and author Jo Carson is Southern Exposure’s fiction editor. (1995)