Not Whistling Dixie

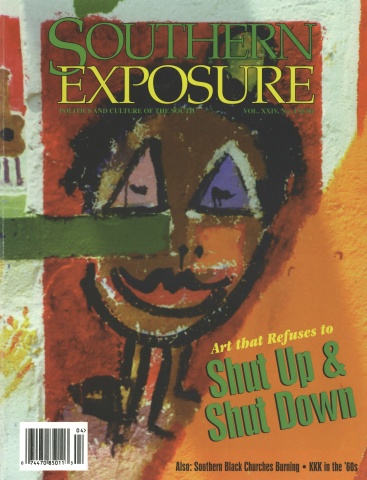

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

“We see despair in the political activist who doggedly goes on and on, turning in the ashes of the same burnt out rhetoric, the same gestures, all imagination spent. Despair, when not the response to absolute physical and moral defeat, is, like war, the failure of the imagination.” — Adrienne Rich, What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics, 1993

Singing, stories, poems, pictures, plays — can any of them lead to social change? Meridith Helton asked Southern Exposure section editors Nayo Watkins (“Voices”) and John O’Neal (“Junebug”), both social activist/artists, to comment.

Nayo Watkins

“The role of art in social change . . . it can be a vehicle to allow people to experience something that takes them to another level or that gives them a reflection of themselves or their world in a way that they see new depth and new meanings.

“Much of what I know being called art for social change is really about personal transformation as opposed to community action. Now, personal transformation has to come about before the action. Or it comes about in the context of community action. But I think most of what is passing for art for social change is . . . someone dances with an elderly person and suddenly has a new understanding of ageism. Someone is in a play or sees a play about AIDS and has a new awakening. Well I don’t call that social change, frankly. I think the social change comes in terms of, ‘So what?’ ‘What then?’

“I’m often at a loss to find examples on how it actually brings about social change. One of the things that comes to my mind is from the 1960s and the role that song played in the dispelling of fear. I have heard the story of McComb, Mississippi, where [there was] a little tiny jailhouse that was really only supposed to hold a few people. They had [civil rights] people stacked in there, and people started singing, and their singing was so forceful, so hopeful, so uncompromised, so fearless, that the jailer was the one who was afraid.

“The empowerment that happens when you know you are challenging a force and overcoming a negative force, that’s an empowerment that I think is real important.

“So often the artist, even the artist who is well meaning, doesn’t get a chance to do some substantial work. And even when they do the emphasis gets put on the end product, whereas what I think is important is this whole process.”

John O’Neal

“Well, without art and culture, the struggle for change gets to be pretty dull, dry, and unforgiving. You know, it may be necessary, but it sure ain’t no fun. And people burn out. The thing that comes to mind is what ol’ Mao used to say: ‘The content of art is politics, and the form of politics is art.’ They are essential to each other. We don’t make art with nothing to say.

“[But] the arts [have] rarely emerged as the central focus for people [in the civil rights movement]. The Freedom Singers, which Bernice [Johnson Reagon] was a part of and the Free Southern Theater, which I was a part of are the only instruments that emerged from the movement where art was the main thing that we did.

“The people who made up the [civil rights] movement were no more appreciative of the role and the function of the arts than average.

“I’d be hard-pressed to make the connection between Andy Young, Marion Barry, and myself. I can’t quite figure it out. We’re doing different things. And yet, we were all strong in that movement. I mean, the politics are no more accountable to the community than the artists are. The only thing that keeps us accountable in any way that’s realistic is the conscience of the person involved. As important as conscience is, it’s not a viable political mechanism.

“We have a problem in the culture, American culture. It’s a pragmatic culture, and people are inclined towards . . . the means that are justified by ends. They will look at the answer in the back of the book rather than solve the problem. That characteristic was no less evident in the people in the civil rights movement than in others. Only when the answer in the back of the book didn’t work, [did we turn to art]. It wasn’t a change in theory. We were just forced by circumstance to be a little more creative.

“What is absent is a broad consciousness among us about what we’re doing and how what we do is related to each other. And I think the movement is going to have to come into focus to make those kinds of connections. And certainly art will be able to play a role in there.

“I think the arts can be a force, but a public instrument is no better than the base upon which it stands. Our movement is pretty small right now. The need for it is great, but the extent to which we are capable of mobilizing people and resources is pretty small, and this despite the fact that some extraordinary things are going on in local communities and some neighborhoods.

“I think that our job, as cultural workers, is to try to study those things [history] and learn from them ourselves and present them in ways that people can have access to the information.

“Working with real people, and talking to the realities of their efforts to make their lives, to make the audience and the community that creates the audience the center of the work. And to aim at a community that is not defined by its exception to the rest of us but is at the heart of our effort to make the whole world a better place to be. . . . [We should ask instead] What is the broad historical problem here that captures and makes it difficult for all of us to live? And how do we make a more just, more humane society that will nurture us all. If we don’t get to that question, then we’re just, as they say, whistling Dixie.”

“Art, I am convinced (as indeed have been many scientists like Pascal and Einstein), is at least as necessary as the sciences in grasping reality if we are ever to effect the change we seek in our long struggle to be human.” — Jean Caiani, Resist, July/August 1996

Tags

Meridith Helton

Meridith Helton goes to Sarah Lawrence and lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She was a Southern Exposure summer intern. (1996)