This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

On August 4, 1994, at just past 2:15 a.m. in the northern Tennessee town of Clarksville near the Kentucky border, the sound of breaking glass shattered the tranquility of the early morning hour. A Molotov cocktail — a bottle of gasoline with a burning rag stuffed in the top — crashed through the window of James and Wilma Johnson’s home, setting the house on fire. Seconds later gunshots rang out. A bullet passed inches from the window to the room where the Johnsons’ young daughter Stephanie slept. As the family tried to escape, a group of young white men belonging to a neo-Nazi group called the Aryan Faction drove back and forth in front of the house taunting them. Finally the assailants fled, but not before leaving a note in the family’s mail box. “Dear Johnson, AF wants you to leave our white community. You Coons! Coon hunting season is open.” The note was signed “AF.”

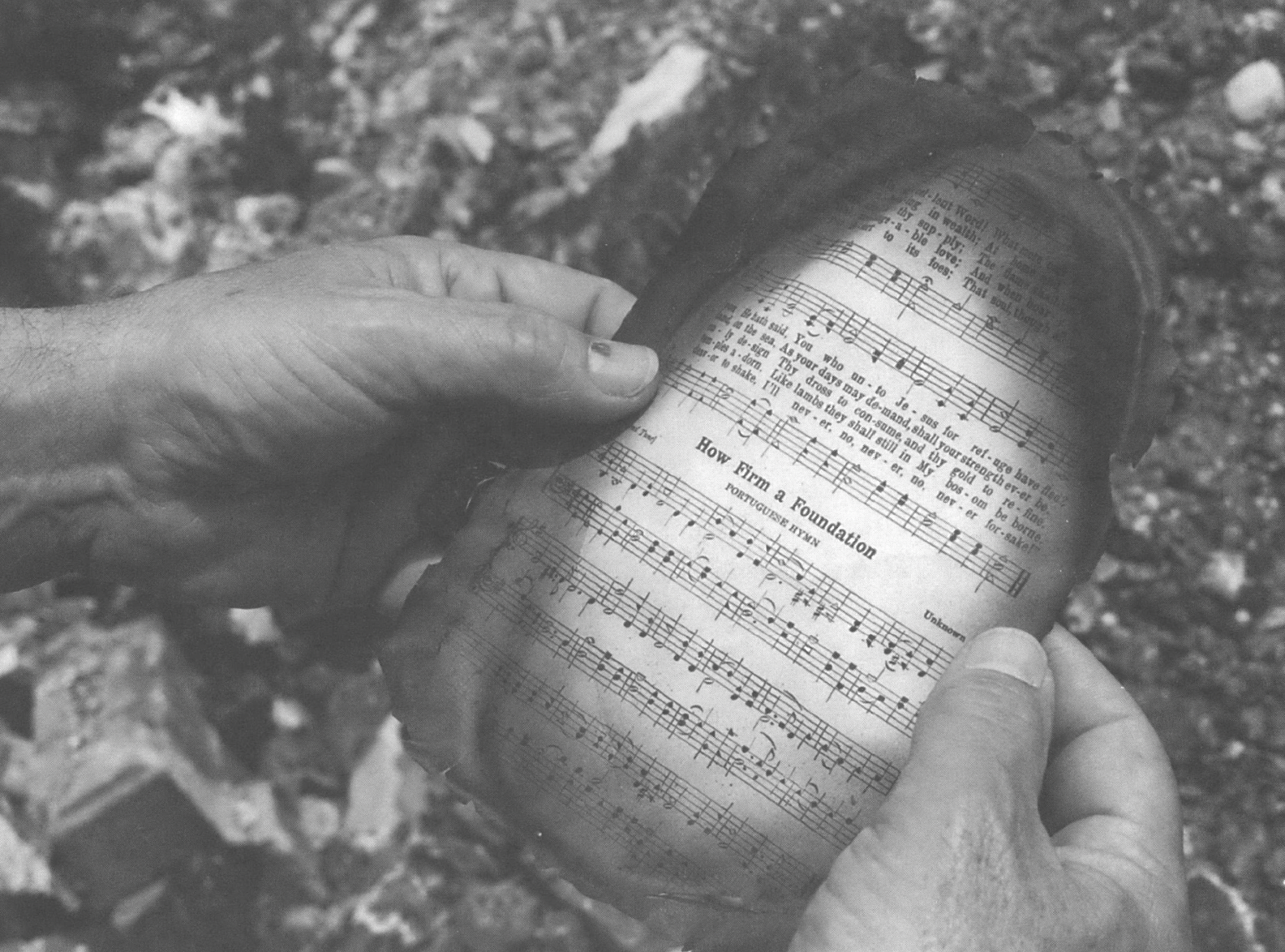

The next day a firebomb destroyed a black church in the community, the Greater Missionary Baptist Church. Investigators did not catch the culprits, but they suspected the Faction because street signs in the area bore the same racist graffiti that the group would later use in other attacks.

Nine days later the Aryan Faction attacked another black family in the same neighborhood. The group broke into the home of William Ewing and Georgia O’Hara. They shattered the couple’s fish tank with a shotgun blast, smashed family pictures, and ransacked the residence. They also stole personal items and set the house on fire with Molotov cocktails. A spokesman for the group then called the local newspaper and took credit for the arson. He told the paper the organization “wanted all niggers out of Montgomery County” and threatened to kill black residents.

In the early hours of August 18, two group members burned the Clarksville Benevolent Lodge No. 210, a meeting place and community center since the 1880s. They spray painted a barbecue pit behind the burned building with racist graffiti. “AF strikes again!” the graffiti read. “Niggers leave or die.”

Members of the group eventually were caught and convicted for the attack on the black residence and lodge though not for the church destruction. But even with the perpetrators behind bars, the attacks in Clarksville terrified black communities across the South. Their fears were well-founded. Within a year, many had experienced similar arson attacks on their churches. According to the FBI and other federal and state law enforcement agencies that comprise the National Church Arson Task Force, fires damaged or destroyed 230 churches in the 21 months following the Clarksville bombings. In the South, more than half of the arsons involved black churches — even though African-American congregations comprise only a fifth of churches in the region. Eighty percent of those arrested for the fires were white.

Law enforcement officials, while admitting that some of the arsons have been inspired by racial hatred, attribute most of the burning of black churches to teen vandals, drunks, and copycat arsonists inspired by news accounts of the fires. Widely cited articles in the New Yorker, Wall Street Journal, and Associated Press also dismissed the epidemic of black-church burnings as exaggerated. They downplayed racism as the fuel behind the fires, emphasizing that some of the arsonists were black parishioners or mentally disturbed individuals. By most estimates, less than one percent of the crimes have been committed by white supremacists.

But the rush by investigators to rule out racial hatred as a cause of the church burnings highlights the fundamental failure of the investigations themselves. Federal and state officials have no way of knowing what role racism played in sparking the blazes for a very simple reason: They haven’t looked. A six-month investigation by Southern Exposure shows that most Southern states do not keep a record of church burnings by race of the congregations. Those that do often fail to share the little information they have with other law enforcement agencies. Local officials fail to investigate adequately many of the fires. Some investigations target church members themselves as suspects, even when evidence points in a different direction.

“In many of these cases, they have no idea who’s burning these churches,” says Rose Sanders, co-founder of the National Voting Rights Museum in Selma, Alabama. “How do they know it’s not racism if they are not looking?”

The slipshod approach to the arson investigation has outraged many in the black community who vividly recall the cross burnings and church bombings of the 1960s. “It’s like we can never move past this type of thing,” says Jo Anna Bland, also with the National Voting Rights Museum. “We’re always fighting the same old racism.”

Bland and other black leaders say the narrow focus on whether white supremacist groups are behind the church fires has blinded authorities to the volatile mix of racial hatred and extreme poverty that serve as a backdrop to the blazes. For many black Southerners, little separates the burning of black churches from other recent attacks on African Americans. In Mississippi, more than 40 black men died in mysterious hangings in jails over a two-year period during the early 1990s. In North Carolina, white soldiers with neo-Nazi ties killed a black couple in Fayetteville a year ago. In Tennessee, the home of a black bus driver in Chattanooga was set ablaze shortly after he filed a complaint of employment discrimination. In South Carolina, a group of white men fired several shots into a crowd of blacks following a rally to keep the Confederate flag flying above the statehouse. In Florida, a group of white teens went on an arson spree and then planned to dress in Disney costumes and shoot blacks. And across the South, more than 20 people were arrested for more than 30 cross burnings last year alone.

“There is no doubt in my mind that there is a connection between these incidents,” says Jim Evans, a Mississippi state representative and president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. “The connection is a deep-seated hatred of blacks reinforced by a climate that makes it O.K. to go out and do these things.”

Who’s Counting?

The pattern of fires at Southern black churches did not come to light until the Center for Democratic Renewal, an Atlanta-based watchdog group, drew national attention to the arsons in 1995. President Clinton responded by forming a federal task force to investigate the blazes, but authorities charged with solving the crimes have consistently failed to document the most basic information of all — the race of parishioners whose churches have been attacked.

Data for the past six years collected from agencies in 12 Southern states where churches have been burned reveal a dearth of reliable information. Although most states do track the total number of church fires, six states keep no information by race — Texas, Arkansas, Kentucky, Virginia, Louisiana, and Florida. Georgia lists some, but not all, of its church arsons by race of the congregations.

To make matters worse, information is not always shared among the agencies that track church fires. Some states do not require local fire departments to report arsons. In Virginia, for example, reporting fire incidents to the state Department of Fire Programs (DFP), the agency that gathers information on arson and other fires, is not mandated by law, says Marion Long, information systems manager at the DFP. According to Long, the DFP gathers information on only 55 percent of all fires in the state each year.

Even when information is collected, it is not always comprehensive. A review of data available at the state and local levels reveals some glaring inconsistencies. In Mississippi, two churches that burned in 1992 as part of a well-publicized arson spree are not listed on the state fire marshal’s report on church fires. In North Carolina, two churches burned in the early ’90s, but these fires do not appear on the list compiled by the State Bureau of Investigation.

“We were lucky to get the data that we have,” says Special Agent in Charge Mike Robinson. “The data are just not kept in one place where you can get your hands on them, and not all fires are actually reported. Anyone in North Carolina can investigate a church fire, but they don’t always report it to us or the fire marshal’s office. So there might be some churches that we miss in our count.”

Accurate data are equally hard to come by at the national level. “If you look at the way data have been kept over the years, you wouldn’t find a difference in the way we classify a bam or a church,” says a spokesperson for the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF). “All you would find is that we investigated an arson.”

The most comprehensive list of fires is kept by the National Fire Protection Association, a Massachusetts-based group that has been widely cited as an authority on the recent outbreak of church arsons. According to the group, the number of church fires nationwide fell steadily from more than 1,420 in 1980 to about 520 in 1994, the last year data were available. But the statistics are misleading. The NFPA, by its own admission, records only between one third and one half of all fires each year — and none of the information is collected by race of the victims.

The NFPA bases its numbers on information provided by the National Fire Incident Report System (NFIRS), which is run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. But because the system is voluntary, only 14,000 of the 30,000 fire departments nationwide bother to report. Some fire departments, especially in the South, shun the system out of an aversion to big government and unfunded mandates. Many volunteer and smaller departments are unable to participate, given the sophisticated coding and data systems required by the system. And fire departments that do report don’t always do so on a consistent basis.

To fill in gaps, the NFPA conducts its own surveys. Fire departments serving large populations generally respond, but smaller departments seldom do. According to the NFPA, less than 25 percent of departments serving 2,500 to 5,000 people participate in the surveys — omitting data from precisely the kind of small communities and rural areas where many black churches have burned.

The lack of complete and reliable information has clearly resulted in the underreporting of arsons at Southern black churches — which in turn prevents authorities from considering the extent to which racial hatred serves as a motive for the crimes. Even the NFPA recognizes that its data has been misused to downplay the role of racism. “People have made a lot of comments using our data,” says David Katter of the association. “We have not made any comments concerning the arsons at black churches concerning the motivation. We just collect the information.”

No Heat, No Light

Inconsistent and inaccurate information is not the only thing hampering investigations into the church fires. Many congregations at burned churches also question the way the probes have been conducted. Investigators have repeatedly neglected important evidence, failed to follow up on leads, and harassed members of the congregations whose churches have been attacked.

In South Carolina, authorities originally told the Reverend Terrace Mackey of Greelyville that the fire at his church was an accident. Later investigators determined that the fire was indeed arson, and that at least one of the men who set the blaze was a member of the Klan. In Arkansas, officials told Reverend Spencer Brown that an electric water heater caused a fire at his church in 1995. The only problem, says Brown, is that the heater was not hooked up at the time. Brown reported the information to the state fire marshal, who promised to pass the information on to the FBI and the ATF. So far, Brown says, neither agency has responded.

Next door in Mississippi, just one federal agent is assigned to work on possible civil rights violations involving 14 black church fires in the state. According to Hal Nielson, a spokesman for the FBI in Jackson, the bureau conducts no systematic investigation of white hate groups in the area to determine if they have any connection with the arsons. “It would not be fair to say that we should go out and question members of these groups every time a church burned in the area,” Nielson says.

Officials have shown no such reluctance to interrogate members of burned churches. “In many cases church members themselves have been questioned about the fires, even when there is clear evidence of racial motivation.” says Rose Johnson of the Center for Democratic Renewal.

When the Inner City Baptist Church in Knoxville, Tennessee, was firebombed last January, officials found the racial slurs “Die Niggers” and “Die Nigger Lovers” painted on the walls. The associate pastor, football star Reggie White, had received phone threats, and local police discovered a letter from the “Skinheads for White Justice” threatening violence. But instead of tracking down white supremacists in the area, local and federal investigators questioned all 400 members of the congregation about their whereabouts during the fire, gave many of the parishioners lie-detector tests, and subpoenaed church financial records. The minister of the church, Reverend David Upton, was questioned at least 10 times in connection with the fire.

Members of black churches destroyed in other Southern states have also been targeted as suspects. The congregation of a black church burned in Selma, Alabama, had to hire an attorney after investigators subpoenaed church records and began questioning church members at their jobs — even though the fire had been ruled accidental. When the Little Zion Baptist Church and Mt. Zoar in Greene County, Alabama, burned last January, officials suggested that black teenagers were responsible for the blaze.

“It was a real disgrace to suggest that perhaps they’d bum down their own churches,” says the Reverend James Carter, an assistant pastor at Little Zion and a former county commissioner. “In this community, our churches are as sacred as our parents. I cannot see a bunch of black teenagers going out and burning churches for fun.”

“A Solid Citizen”

Perhaps no one embodies this pattern of targeting the victims better than James Ingram, who is coordinating the investigation of church fires in Mississippi. As director of public safety for the state, Ingram downplays the seriousness of the recent attacks. “We haven’t had the same problem with church fires here in Mississippi that other states have had,” he insists.

On the surface, Ingram seems to have the perfect credentials for investigating hate crimes. As head of the FBI in the state during the 1960s, he investigated the burnings of several black churches — as well as the murders of civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman. Many say that the heroic FBI agent portrayed in the Hollywood movie Mississippi Burning was based on Ingram.

But Ingram has a little-known history of working to undermine black citizens in Mississippi. At the same time that he was supposedly investigating racially motivated attacks during the ’60s, Ingram also served in the FBI Division Five “Racial Intelligence” Section which carried out the notorious counterintelligence program known as COINTELPRO. The purpose of the program, according to a 1967 memo by then-FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, was to “disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize black nationalist hate-type organizations.” The program targeted black leaders such as Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokely Carmichael, Elijah Mohammed of the Nation of Islam, and the Black Panther Party.

After details from COINTELPRO were released, Ingram was sued for violating the civil rights of Muhammed Kenyatta, a student activist at Tougaloo College. Ingram and two other FBI agents forged a letter to Kenyatta from a student group threatening him with physical harm if he set foot on campus. The forgers spelled out their intent in an FBI document obtained under the Freedom of Information Act: “It is hoped that this letter if approved and forwarded to [Kenyatta] will give him the impression that he has been discredited at Tougaloo College and is no longer welcome there.” The document concluded: “It may possibly also cause him to leave Mississippi.”

Kenyatta received the forged letter a few days after someone fired shots into his car. He left Mississippi shortly afterward.

Ingram offers no apologies for his role in the counterintelligence program. “I was an employee of the FBI for more than 30 years, and during that time there were certain duties that we were asked and instructed to do,” he says. “And one was the counterintelligence program. But that’s long past history. But at the same time, ask any individual in Mississippi, and certainly the black community, and you’ll find that Jim Ingram has been a solid citizen to them.”

Black leaders disagree. “Did you ask him to identify any black leaders he had a good relationship with in the state of Mississippi?” asks Obie Clark of the NAACP in Meridian. “I don’t know who he’s talking about.”

Others point to Ingram’s poor record of investigating crimes in the black community. Until the 1993 conviction of three white teens, no one had ever been convicted of burning a church in the state of Mississippi. “Ask Mr. Ingram how many church fires he solved in the ’60s,” says Charles Tisdale, publisher of the weekly black newspaper The Jackson Advocate. “I don’t trust him to find anything.”

Protest by Proxy

Despite the shoddy work by investigators, evidence of racial motivation has emerged in a number of attacks on black churches. A review of arrests from federal and state records over the past six years shows that at least 30 arsonists charged with burning black houses of worship were driven by racial hatred.

John David Knowlton, a 57-year-old small engine repairman, was arrested in July for burning the Evangelist Temple Church of God in Christ, a black church in Marianna, Florida. Knowlton, who had lived next door to the church for eight years, filed a complaint in 1993 claiming that members “beat drums late into the night.” A prosecutor refused to press charges, and court records show that the minister agreed to muffle the drums “so that the music wouldn’t disturb Knowlton.” Although Knowlton claimed no knowledge of the church fire, several eyewitnesses saw him leaving the church with a gas can shortly before the blaze. Police later found racial slurs — including the word “Nigga” — scrawled on the walls of Knowlton’s former home. One of Knowlton’s children later told investigators a member of the family had previously talked about the Evangelist Temple, saying, “The place should have burned down.”

In other cases, attacks on black churches have been orchestrated by white hate groups. In the Greelyville, South Carolina, incident, police charged four men in 1995 with burning the Mount Zion A.M.E. Church as well as the Macedonian Baptist Church in Bloomville. Police said one of the men carried a card in his pocket identifying him as a member of the Christian Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

Although some blame a conspiracy of white hate groups for the fires at black churches, those who have studied the crimes say the real culprit may be more elusive — and far more dangerous. “I wish it were only a few hardened hate mongers,” says Dr. Jack Levin, director of the Program for the Study of Violence and Social Conflict at Northeastern University and co-author of Hate Crimes: The Rising Tide of Bigotry and Bloodshed. “We’d have a particular enemy to go after.”

Levin says that law enforcement officials won’t find racism as the root cause of the black church fires if they use the convictions of white supremacists as their barometer. Research conducted by Levin and co-author Jack McDevitt shows that members of organized groups commit less than one percent of hate crimes. Most are committed by “thrill offenders” — criminals often dismissed by police as just kids causing trouble.

But according to Levin, the real motivations are rooted in widespread racism and economic insecurity. Levin, who has prepared profiles of church burning suspects for several law enforcement agencies, says his initial review suggests that the “overwhelming majority of the arsons can be blamed on young, mostly white men.” Some of the perpetrators have certainly been exposed to racial hatred, says Levin, but most are probably motivated by resentment over their bleak economic future. Blacks are targets because they “stand in for the real enemy.” When these young people who aren’t doing well see affirmative action or attention to the underclass, they feel quite ignored,” Levin says. The burning of black churches is “protest by proxy.”

Racial hatred also plays a role in the so-called “copycat crimes,” says Levin. Those who mimic acts of violence motivated by hatred are themselves inspired by that hatred. “They are participating in a second-generation hate crime.”

Heeding the Message

The findings by Levin are echoed in the history of black communities across the South. “That’s why these skinhead groups are rising,” says Reggie White, associate pastor of the church that burned earlier this year in Knoxville, Tennessee. “Those racist attitudes are still out there, and too often we’ve forgotten our history. We don’t want to think about lynchings; we don’t think about the burning churches.”

The role of racism in sparking the church fires is also confirmed by the results of a three-month study released in October by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, the federal agency charged with promoting voting rights and equal opportunity in housing, education, and employment. The commission found racism rampant in the states where the black church burnings occurred.

“It’s depressing,” says Melvin Jenkins, director of the commission’s central region, which includes much of the South. “I think the fires were simply a message, even if some are not racially motivated. It was a message that we need to discuss race-honestly, particularly in those Southern states.”

Joel Williamson, a humanities professor at the University of North Carolina and a scholar of Southern history and violence, sees an even broader message in the church burnings. “It’s a sign to the controlling elites that something is wrong,” he says. “Downsizing, growing disparities between rich and poor, the burnings, and other attacks are a shot across the bow — a warning. It’s amazing that no one has been killed.”

So far, though, authorities have failed to heed the message. Even when law enforcement officials arrest a suspect in a church burning, they often fail to consider racism as a motive. “Many take the viewpoint that you have the person in jail, so why look for another motive for the crime?” says Barron Lankster, a district attorney in Demopolis, Alabama. “In the South a suspect would almost have to say, ‘I did this because the person was black’ before people would believe it’s a hate crime.”

The tendency of authorities to downplay racism as a motive makes it unlikely that many of the arsonists will ever be caught — and even more unlikely that those who are apprehended will ever be prosecuted. National figures show that only 15 percent of all arson cases actually end in arrest. Most of those are inside jobs. According to federal data, only 5 percent of ATF cases referred to the Justice Department are for arsons. And only 5 percent of all civil rights cases are ever prosecuted by the Justice Department.

Although black leaders who have called attention to the crimes have been blamed for sparking further violence, groups like the Center for Democratic Renewal have vowed to keep the pressure on federal officials to take action. The best hope, they insist, lies in increased public scrutiny and pushing for tougher penalties and enforcement of laws for burning houses of worship.

“That’s the most that we can hope for,” says Noah Chandler of the CDR. “Unfortunately, hatred will always be with us. But we have to send a strong message to people who practice this type of behavior that this will not be tolerated.”

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.