Community Newspapers

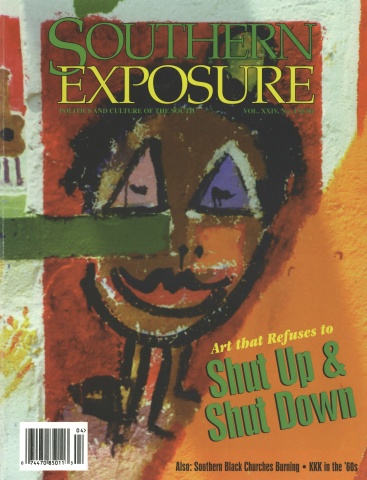

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 4, "Art that Refuses to Shut Up & Shut Down." Find more from that issue here.

Because most daily, mainstream Southern papers depend on profits and must be careful not to alienate advertisers, it falls to community newspapers to cover issues shunned by bigger media enterprises.

Such papers have a long and distinguished history. The Manumission Intelligencer, the South’s first abolitionist paper, began publishing in Jonesborough, Tennessee, in 1819 for six subscribers. The Anvil, an underground paper in Durham, North Carolina, dogged politicians in the ’60s and ’70s. The Plow, published in Southwest Virginia in the 1970s, offered a place for Appalachians to work out their own destiny.

Today, most Southern towns of any size have publications covering women’s issues, gay men and lesbians, the black community, environmental issues, politics and social issues, and entertainment. Profits and fame aren’t the factors that move people to get involved in producing these papers. Southern Exposure talked with a few of the people involved with some of the dozens of small community papers across the South specifically dedicated to social change.

The nonprofit Point in Columbia, South Carolina, is a typical community newspaper. The free 16-page tabloid, which is distributed across the state, focuses on South Carolina politics and carries some local advertising.

The paper began as a weekly in 1990, but the pace was too fast and the work too much for the small staff. They revamped the paper as a monthly. Restructuring didn’t make it that much easier. Becci Robbins, the 35-year-old editor of Point, said that even today the paper is struggling.

Robbins has no regrets. Before her six years at Point, she put out a magazine and newsletters at the South Carolina Bar Association. Though she picked up the “nuts and bolts” of publishing there, she soon felt repressed and stifled, she said recently. When she came to Point, she did an article on an AIDS service organization, and fulfilled activist longings which had lain dormant all her life. “I owe something back to the community,” she said.

The paper supports local and state progressive politics and culture, and tries to foster local talent by publishing local writers. Like most community papers, writers work for free, but the contributors do not go unrewarded. Point “provides a stage for people to perform on.” The monthly also provides a forum for “dissatisfied citizens” whose voices are not always heard in bigger news organs, said Robbins.

The more investigative articles in Point deal with issues that bigger papers either can’t or won’t touch. A recent article examined how politicians can become addicted to polls, tailoring their platforms to the latest results—not to issues important to their constituents.

Point should not be pigeonholed as a left-wing publication, said its editor. “Point tries to peel it all back and go beyond partisanship.” The paper encourages activism with a “Do Something!” section, which is “a bulletin board for political and social activist groups to post upcoming events.”

The Prism—an all-volunteer, monthly out of Durham, Raleigh and Chapel Hill, North Carolina—is unabashedly leftwing. A group formed to start The Prism seven years ago “because no paper in this area provided a forum for political analysis, opinion and news beyond isolated items,” said David Kirsh, an editor and distribution coordinator. He and his wife, Mia Kirsh, who works on production and is treasurer of the not-for-profit corporation that runs the paper, joined a dozen others including some members of the Orange County Greens to start a publication that would be written by people in the community, especially those who are underrepresented in other media.

As Jeff Saviano, another editor, put it, “We hope to forge stronger and stronger links between all types of leaders and members in grassroots community activism but that task is difficult because there are no easy models to copy from—in fact, we believe we’re trying something new.”

“Over our seven years, I think we have succeeded in publishing many diverse voices that previously had no way to communicate,” said Mia Kirsh.

Getting the paper off the ground took time. “It was very painful. Every aspect of the paper had to be hashed out for days and days. It took about nine months to get it off the ground, about like having a baby,” said Kirsh. “In fact, I was pregnant at the time and gave birth to my daughter after the first issue came out,” she added.

The labor paid off. Many policies decided in the beginning are still in place. “We decided we’d never have more than 20 percent of the space devoted to advertising so that we’d have lots of print. We decided that none of the staff could personally subsidize the paper so that no one would have undue influence.” It’s worked out so that approximately 70 percent of the paper’s income comes from advertising with the rest made up of donations. The paper is free at racks in the area, but it can be ordered by mail. Because there is an all-volunteer staff, costs remain low. The approximately $500 to print 6,500 copies of each issue is usually the only expense.

It takes “around a dozen with a core group of around four of us” to do all the editing, production, and distribution, said Mia Kirsh, who is also Southern Exposure’s designer.

The paper covers a range of issues. David Kirsh explained, “There has always been some tension in creating a balance between our desire to cover local issues and the ease with which we can get people to write on national and international issues. But we try to point out the interconnectedness of the issues—between the local and the not-so-local, between the attacks on the social safety net and declining real wages, between the media circus around O.J. Simpson and the promotion of Nazi race science.” The Prism has covered health reform and welfare reform. There was a series called “Belly of the Beast” written by a 20-year veteran of the Green Berets and the Army who exposed the true aims of U.S. foreign policy. And the paper recently did a two-part investigative piece on homelessness in Durham.

A regular column, “Eye on the Media,” offers local and national media criticism. “Ask Kropotkin” is a sardonic political advice column. The paper has also featured columns reviewing books for children and on products made by progressive companies.

The people who put together The Prism have other jobs and fit their newspaper effort into hectic evenings and weekends.

Moon, a free bi-weekly newsmagazine in the Gainesville, Florida, area has served for the past six years as a watchdog, exposing the dark side of politics in the northern Florida city. Writer and publishing board member Colin Whitworth, 31, a former reporter for a daily newspaper in central Florida, said the inspiration for founding the paper along with four other writers disillusioned with big-paper politics, was “a distaste for mainstream journalism.” The bigger papers are afraid to pursue stories that would alienate commercial interests. Moon, by contrast, tries to be a vehicle for information important to the community. “[We try] to lend a hand in helping people in seeing how things work so they can decide what to do,” Whitworth said.

A report last year on campaign contributions to city and state government candidates and officials showed the strong economic influence builders and contractors exerted on local government. This work caught the eye of The Gainesville Sun, and they published a report on campaign contributions shortly afterwards. “We made them look bad because we did something they wouldn’t think of doing,” Whitworth said.

Another community newspaper which takes its social responsibility seriously is The Trumpet of Conscience, an 11-year-old free quarterly newsletter with four to eight pages for Durham, North Carolina, and the surrounding area.

The founder and publisher of The Trumpet of Conscience, Sam Reed, is an 88-year-old activist who organized unemployed workers during the Depression and helped union workers in the electrical, steel, auto, and mining industries in the ’50s and ’60s in Pittsburgh. Reed, who is also an army veteran of World War II, has been involved in the Durham political scene for 23 years.

“The whole starting point of The Trumpet of Conscience was the legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr., “ said Reed. Mainstream media are restrained by commercial interests, “the power structure, those that own 80 percent of the wealth of the country and make up 2 percent of the population,” he said.

The Trumpet of Conscience tries to combine the variety of mainstream press with the purpose and mission of activist groups. Reed pointed out that voter education must precede voter registration. “If the voters don’t read, don’t reason, you can register everybody in the city, and this isn’t enough.”

The Trumpet also sponsors events that recognize and bring together community activists. At a Labor Day program this year, union workers and friends discussed a voter education plan for the November 5th election, “with a focus upon labor issues and the economic well-being of the forgotten majority.”

In addition to reaching people at the grassroots level, Reed listed among his 4,000 readers “all four floors” of city hall, the chair of the board of education in Durham, and the chancellor of North Carolina Central University. The newsletter also goes to state politicians, local libraries, bookstores, bakeries, and the major universities in the area. The Trumpet, Reed says, “tries to follow the teachings of Martin Luther King, Jr.—organize to fight for opportunities, organize to fight injustice. We are part of the struggle for centuries of the common people against oppression,” he said. “The Trumpet of Conscience doesn’t solve all their problems. . . . We try to be an example of the importance of bringing people together. Without that, you can’t fight drugs, discrimination, or corruption.”

Tags

Eric Goldman

Eric Goldman recently received a master’s degree in English from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and worked as a Southern Exposure intern. (1996)