This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 3, "Way Up North in Dixie." Find more from that issue here.

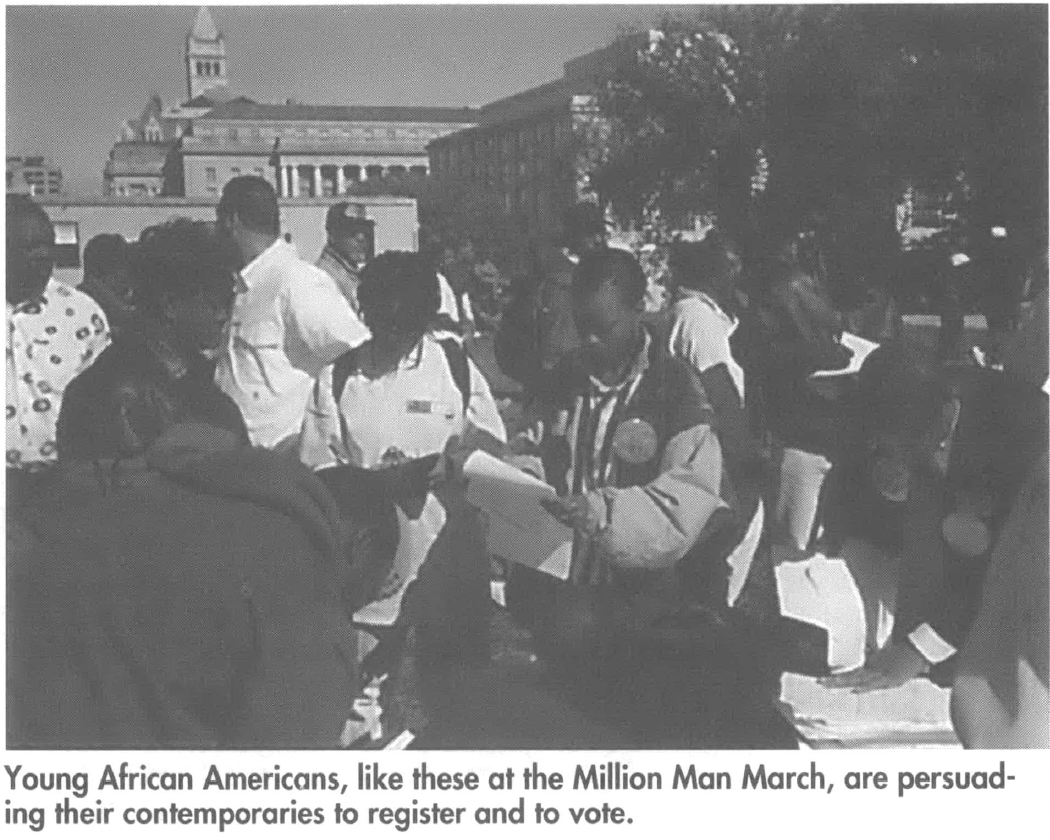

Dennis Rogers, national director of Black Youth Vote, has never met Jolynn Brooks of Common Agenda. Nancy Ware’s Reclaim Our Youth Project probably doesn’t work with Rhamelle Green of the Zulu Nation in New York City. But it doesn’t matter — they’re all working together. They plan to get 1.2 million young African Americans to the polls this November — twice the number of those who voted in 1992.

The problem is that most of the people that Rogers and his colleagues are trying to attract are not interested in the political process — or in voting. Of four million eligible African Americans between the ages of 18 and 24 nationwide, only 638,000 showed up at the polls in 1992. That’s lower than any other group in any age category. Only 14 percent of black men between 18 and 24 voted, and black women of the same age only did a little better at 19 percent. Older people can be counted on to vote—black women between the ages of 55 to 65 had a higher turnout, at 73 percent of their registered numbers. But the young stay away in droves, especially young blacks.

Although apathy plays a part, most voting rights activists and community leaders say the reasons for not voting go deeper. Young adults sense that the corruption and conservatism of government officials runs so deep that any hope for positive change is stifled. “Elections are bought and sold, candidates are manipulated, and young people can see that,” says Jolynn Brooks, national director of Common Agenda Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based federal budget analysis organization.

Many young people aren’t aware of the power that lies within the political process, and they don’t recognize the impact it has on their lives. “Most people see themselves as isolated from that picture, or any other big picture, for that matter,” said Zulu Nation spokeswoman Rhamelle Green. “These days, people are too afraid to even talk to their neighbors. They would rather try to solve their problems on their own.”

Nancy Ware, executive director of Citizenship Education Fund’s Reclaim Our Youth Project in Washington, D.C., agrees with Green and looks beyond. “Too many young adults don’t even know who their political representatives are,” said Ware. “It’s not just apathy, because there are so many who are eager to make their communities better. They just don’t know the process or its value. When they do, they become charged and they act on it.”

Some young African Americans around the South have gotten charged and are recruiting more voters around the region. Dennis Rogers of Black Youth Vote, a division of the National Coalition of Black Voter Participation, registered 15,000 young adults at Atlanta’s Freedomfest last spring. Formerly known as Freaknik, the annual spring break event is generally attended by thousands of black college students. Although in past years Atlanta residents have seen the student event as pandemonium, this year the National Coalition, the Freedomfest Committee, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and other youth and Southern groups worked together to present cultural and entertainment activities for vacationing students. And they challenged thousands of college students to become part of the political process.

The Black Student Leadership Network (BSLN) in Washington, D.C., has a plan to bring voter registration to campus computers: when students register for classes, they register to vote. “We want voting to be incorporated into the system,” explains Darriel Hoy, BSLN Southern regional field director in Durham, North Carolina. “We have 11 HBCUs [historic black colleges and universities] and over 20,000 black students in North Carolina,” said the 24-year-old Duke University graduate. “That’s a potentially strong influence over our politics.”

BSLN is also training student leaders at summer “Freedom Schools” around the country to get new registrants souped up about voting. “The whole idea is to get people to take the strategies back to school this fall,” Hoy said. “It’s so important to get young people thinking about the political process and how it affects them.” Freedom Schools train more than 200 high school and college leaders in leadership and activism. “We are going to create a buzz on campuses,” Hoy said. “We’ll be on school PA systems, on bulletin boards at concerts and parties, on radio stations — we’ll even develop student discounts to events if they can produce their voter registration cards at the door.”

The National Coalition for Black Voter Participation, a 20-year-old organization with a membership of more than 70 groups, is trying to make the National Voter Registration Act a reality. Under the terms of the act, (also referred to as the “Motor Voter” bill) which President Clinton signed in 1993, people can register to vote when they apply for a driver’s license. “Too many state legislatures are ignoring the principles of the act,” said executive director James Ferguson. “We are in the process of looking at those states and developing litigation against them.”

Ferguson and other members of the coalition see lost potential because of poor implementation of the act, which was supposed to go into effect this year. Just to show it means business, the coalition, working with its affiliated organizations, filed suit in July against Maryland Democratic Governor Parris Glendening for not complying with the Motor Voter bill. “We want to pressure these states into complying with the law,” Ferguson said. “And with the support of our member organizations, we intend to win.”

The Youth Task Force in Atlanta and 21st Century Leadership in Selma, Alabama, plan to run young people in future local and state elections as part of their Black Youth Agenda: Countdown 2000. The agenda was developed by more than 600 young people from across the nation who met in Selma last year to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act and the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery. According to Angela Brown of the Youth Task Force, young people will be organizing to address problems affecting them. “The goal of running young people for office is not to win, but to be able to have a voice in the political process,” said Brown.

Although these efforts are attracting young voters, those who are working to get out the vote agree that young people need to realize that

they can make a difference on issues directly affecting them, including proposed cuts in student loans and other college financial aid and teen curfews. Until these potential voters understand the political process, their turnout at the polls will be low. “It’s going to be a long, educational process,” Ware said, “but I know we’re up to it.”

Tags

Raoul Dennis

Raoul Dennis is a freelance writer in Washington, D.C. (1996)