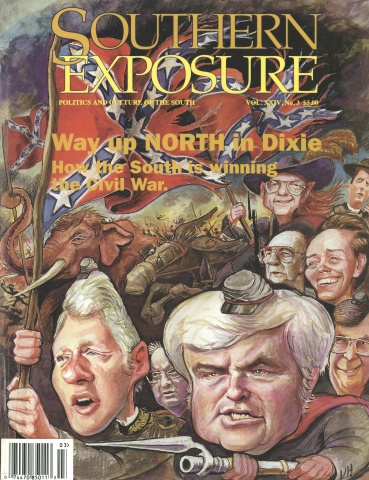

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 3, "Way Up North in Dixie." Find more from that issue here.

Grocery stores in Dekalb County, Georgia, kicked us off the property for soliciting, though we “sold” only voter registration information. One person who took our union flyer asked if we were communists. Another accepted the flier graciously, then threw it in the trash.

Police in Eatonton, Georgia, accused two black Union Summer activists of having guns and frisked them. The officers looked at the activists’ Chicago and New York driver’s licenses with suspicion. The organizers were simply passing out union information to nursing home employees.

A veteran organizer and I gave union fliers to employees outside a paper bag company at 10:50 p.m. — just before the shift change. As cars pulled up to the plant’s gate to drop off and pick up workers, five police cars pulled up. An officer looked at the two of us with our fliers and asked the security guard, “This is the big crowd?” He asked us if the 30-some people entering and leaving the plant were with us. “No, they work here,” we said.

We were watched by the management of the bag company at our Valdosta, Georgia, hotel. Our car was tailed by supervisors from another company. Employers at the targeted Georgia War Veterans Home in Milledgeville passed out papers rebutting our handouts, and nursing home workers in Valdosta found anti-union literature in their pay envelopes.

Welcome to Union Summer.

While others crossed two times zones to fly into the Atlanta airport to participate in Union Summer, I spent an hour and a half driving down I-75 South from Chattanooga, Tennessee. Just a few years ago in high school I had come to Atlanta for concerts or movies that weren’t mainstream enough to play in my hometown. I never saw the Atlanta where people could not afford to drive 117 miles for a show.

After I graduated I went to school in New York City where I learned about civil rights struggles of the past. I had grown up amidst the movement but largely ignorant of it. In my insular background, Atlanta had meant nothing more than good shopping. Now I wondered if I could put up a good fight.

Then I met the 37 other Union Summer activists in my group and had another concern. They came from 16 states mostly outside the South. Could I deal with their criticisms of my region? Though I might agree with their views, I retained a weird combination of pride and anger about the South. It’s like relatives. I don’t choose them. I don’t always like them. But I love them. And I don’t want to hear about their too-obvious flaws from anyone outside the family.

Yet, it was hard to think about trying to change my own home. It was easier to protest in the face of the New York Police Department in riot gear as they handcuffed eight students and smashed another’s face in — as I did at a demonstration against New York City budget cuts — than it was to tell someone in my home community that he’s racist, sexist, or homophobic. But no amount of growth in New York will do much good if I can’t apply it at home.

Out of the 15 Union Summer sites nationally, I participated in the South as a test. Could I act on beliefs that I hadn’t had the nerve to assert here before?

Most of the members of my group were, like me, 22-year-old college students; half were black, and most came from the East, though three were from Portland, Oregon. There was Amity Hough, who went to school in Michigan and volunteered at the Olympics after her Union Summer stint. Sattara Lenz was a student organizer from Brooklyn College I had first seen at a rally in Chinatown last spring. Wes Stitt from Annapolis, Maryland, was a member of his college’s Juggling Socialists Club. Matt D’Amico studied the philosophy of “aesthetic realism” at Baruch College in Manhattan, and Bachir Dussek was a poet and informed conspiracy theorist from the Bronx. Will Kopp, a North Carolinian who went to Brooklyn College, and I went to the same summer camp. Hope Neighbor from Portland joined the Peace Corps and was headed to Cameroon. Andy Lee Davis formed a labor caucus in the Arkansas Young Democrats and taught us the hog call. Patrice Nelson from Chicago planned to teach English overseas in the fall, and Maria Amado studied the working conditions on banana plantations at her home in Panama.

As students well used to paper cuts, we were prepared for the job of leafletting. We handed out fliers for a town hall meeting about the need for higher wages. We gave out union information and authorization cards that would allow the union to represent the worker. We distributed Georgia primary election notices and signs: “Privatize — and we will organize.”

We gave out our paper, cards, and posters as people came off the graveyard shift, when they went on at 3:00 and 11:00 pm, and when the 9-to-5 crowd headed for the subway. We stuck our literature in screen doors of homes and under the windshields of cars. We passed, posted, and waved our signs at Macon, Savannah, and Atlanta rallies, at Dekalb County churches on Sunday, and in front of Walmarts, Kmarts, and Krogers on Saturdays.

As we pushed for better working conditions for factory and hospital workers during our three weeks as organizers, we asked each other, “What about our long hours?” We joked about worker’s comp for the paper cuts.

We arrived June 9, exactly one month before Georgia’s primary elections. For us this meant loading 18 to 20 deep in a 16-passenger van to “walk the walk” with “Get out the Vote” fliers.

Since the Georgia 11th congressional district, dominated by African-American voters from west Atlanta to Savannah, had been struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court (along with districts in North Carolina and Texas), we were encouraging voting in an historic election. We met United States Representative Cynthia McKinney (D), who won her seat four years ago in the 65 percent black 11th District but ran this summer in the 35 percent black 4th District that encompasses one and a quarter counties in metro Atlanta. The 30 percent didn’t move — the district lines did. She did win the primary, and now she faces a stiff challenge in November.

It remained to be seen whether a white majority would elect a black woman, McKinney said. Her re-election would be an important reassertion of the voice of working people, women, and people of color in spite of the Supreme Court ruling, she said.

On weekends we generally leafletted in Atlanta and then took to rural Georgia. Nineteen of us worked with the United Food and Commercial Union (UFCW) Local 1996 and the other 18 with the Georgia State Employees Union (GSEU).

My work with the UFCW over the three-week internship consisted mainly of leafletting as we started new campaigns at poultry plants in Gainesville, Georgia, and nursing homes in Albany and Union Point, Georgia, among others. Despite employer intimidation, a majority of workers took information, took more for their coworkers, and asked, “What took y’all so long?” One man saw the word “union” and not 10 feet from the plant’s gate completed the response card with his name and address. He checked “yes” to the question, “Would you like to be on the organizing committee?” That same day, our leafletting flurry outside a bag manufacturer in Valdosta got the attention of workers at a concrete company down the street who came over for information.

Despite positive reactions, it was disappointing to catch the organizing campaign at such an early stage. Our counterparts with the Georgia State Employees Union embarked on work that seemed more urgent. To save money, the state of Georgia contracted a private firm to run the War Veterans Home, a division of Central State Hospital, one of the largest employers in the town of Milledgeville. The company, Privatrend, agreed to retain only 30 percent of the workforce. They said they would consider hiring back the other 70 percent of the workers on a part-time basis with a minimum $9,000 cut in pay.

On July 1, just one day after we were to complete our Union Summer session, state jobs would fall into private hands. The union wanted to sign a majority of workers before Privatrend took over so that those losing their lucrative state jobs would have leverage with the private company. In the second week of June, the Union Summer activists started the legwork with all that was available to them — a five-year-old list of employees’ names and addresses. They divided up the list and took to the back roads, often receiving sketchy directions — “turn yonder and go up a ways.” They urged workers to sign a petition for union representation and to get involved in organizing themselves.

One Union Summer group of three or four with GSEU reported that they were pursued by ABC News crews. They arrived at homes to find workers out on their front porches, but after five minutes of camera set-up just to film the activists’ trip to the front door, not surprisingly, no one appeared to be home.

By June 27, after talking to workers at home and outside of work and organizing demonstrations and fish fries, the participants had helped to sign up 80 percent of the War Veterans Home employees. With a letter in hand demanding union recognition, the 18 Union Summer activists accompanied Georgia State Employees Union organizers and members to the offices of Privatrend, the soon-to-be managers of the state’s War Veterans Home.

One of the Union Summer participants, Carol Roth, said that employers’ anti-union actions discussed in our training sessions became real to her when Privatrend personnel pushed away letter bearer Tyrone Freeman. Privatrend staff warned each other not to touch the letter.

The new managers called security on the GSEU group. Terrica Redfield, who went home after Union Summer ready to organize poultry workers in her hometown of McComb, Mississippi, said that “security couldn’t do anything, because we weren’t doing anything” save handing over a letter. Though new to Georgia, another Union Summer participant, E’an Todd, felt like the jobs lost at the Veteran Home were just the start and that, in fact, all 10,000 at the Central State Hospital were at stake. He believed that the union campaign was “key to how things are going to go in [the state’s] politics.” After the three weeks of Union Summer had passed, E’an took to sleeping at the GSEU office to see the struggle through, though a job awaited him at home in Portland.

Carol Roth, Al Loise, and Beth MacBlane were prepared to return to Atlanta from their homes in Virginia and New York to continue helping with the GSEU campaign. Another two Union Summer participants postponed return trips home to Florida and stayed in Atlanta to see the outcome of the union’s appeal to the National Labor Relations Board. Several others from Arkansas to Queens stayed on with the textile workers’ union UNITE! They started undercover research at targeted companies where they will work for slightly above minimum wage while organizing their co-workers for higher pay.

Other Union Summer activists I talked to showed equal investment in their work. Amanda Johnson, a fiction writer, said that she started on the United Steel Workers of America’s corporate campaign against Bridgestone/Firestone in Nashville, Tennessee, saying, “I’m not going to be an organizer.” She went on to organize a prayer breakfast with Nashville clergy with only two weeks to get out invitations and make calls. She pinned down a caterer the day before the event. She hoped to enlist the religious community to present the names of 500 locked out employees at the Bridgestone/Firestone corporate headquarters during a massive demonstration in July.

In Georgia’s first Union Summer wave, we started with 37 people and ended with 34. Nationally, there were 1,500 Union Summer participants and more than 3,000 applicants. At some points it was a “logistical nightmare,” according to Andy Levin, the program’s director. Despite this, he told me mid-summer that it was “going great, and the only question now is how to keep Union Summer people involved.” If our group in Atlanta or activists in Nashville are any example, that’s one problem he doesn’t have to worry about.

Tags

Meridith Helton

Meridith Helton goes to Sarah Lawrence and lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She was a Southern Exposure summer intern. (1996)