Swinging the Vote

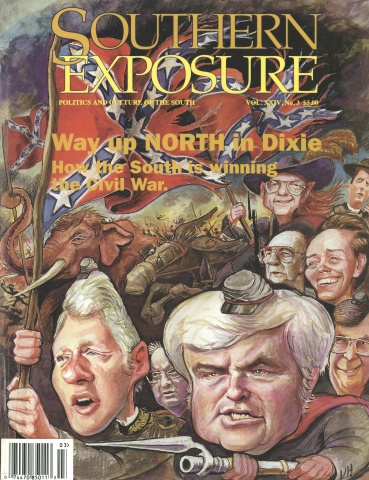

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 3, "Way Up North in Dixie." Find more from that issue here.

In recent years, the once-Democratic state of Texas has been growing conservative — so much so that President Bill Clinton almost decided to cut it out of his 1996 campaign strategy, conceding the state already lost to Republican challenger Bob Dole. But that was before Victor Morales entered the scene.

Morales teaches government at Poteet High School in Mesquite, Texas, a small town outside Dallas. After the 1994 election, he became alarmed by growing anti-Latino rhetoric and the passage of California’s Proposition 187, an initiative denying public services to illegal immigrants. When presidential hopeful Senator Phil Gramm (R-Texas) also spoke out against affirmative action, bilingual education, and Mexican immigrants, Morales decided he would challenge Gramm.

A political outsider, Morales received no support from the Democratic Party or most Latino elected officials. His campaign was considered almost comical. But Morales, whom Texas political analysts claimed owed his support to voter confusion between him and Texas Attorney General Dan Morales, offered more than just a familiar last name. For many Texas voters, his position as a Washington outsider was attractive. For Texas Latinos, his candidacy also offered a rare opportunity to gain new, high-level representation in Congress.

In a true grassroots campaign, Morales logged over 60,000 miles in his pickup. On March 12, 1996, he shocked the Texas political establishment by earning a runoff berth against Congressman John Bryant (D-Texas).

Said Morales, “Interviewing the analysts, over and over they’d say the same thing: ‘Obviously it’s the Dan Morales name recognition,’ and I’d think, ‘What about the sweat, what about my driving city after city, what about me hustling to get on the media in every town that there was — what about that?’”

On April 9, 1996, after the runoff results revealed Morales the narrow victor, no one could blame confusion any longer. Latino voters had provided the swing vote.

Post-election analysis showed that Bryant had carried more counties and more general regions of the state than Morales. But Morales won south and west Texas, areas with large Latino populations and high voter turnout in the primary. Morales had provided an incentive to go to the polls. In November his name will appear on the ballot just below the presidential nominees.

Andy Hernandez, Democratic National Committee Latino Voter Outreach director, has not ignored the Morales factor. “We hope to build off the Victor Morales campaign,” says Hernandez. “Victor will definitely get Latinos to the polls. He offers a sharp contrast to Gramm. He can only help the president and hurt Gramm.”

The Republican strategy in Texas is simply to hold the line. “I’ll be happy if I can keep my base of 30 to 35 percent Latino support,” says Frank Alvarez, director of Hispanic media outreach for the Texas Republican Party, which plans to host a Hispanic Republican Leadership Summit Conference in September. He’s confident he can hold the line. Minimizing the show of support for Morales, Alvarez said the political newcomer poses no threat to Gramm and will only garner “the normal share of Hispanic votes.”

Politics Latino Style: Texas and Florida

Look at Latino voters in Texas and Florida, and you’ll see a reverse image. While roughly 70 percent of Latino voters in Texas support the Democratic party and 30 percent favor the Republicans, Latinos in Florida favor the Republican party by 70 percent and the Democrats by 30 percent. In both states, the Latino vote could be critical.

Democratic Latinos in Conservative Texas

Once known as a “yellow dog” state (suggesting Texans were such staunch Democrats they would vote for a yellow dog if it appeared on the Democratic slate), Texas has seen an overall conservative shift in recent years. The last Democratic presidential candidate to win Texas was Jimmy Carter in 1976. In 1994, Governor Ann Richards, who enjoyed enormous approval ratings, was defeated by Republican George Bush Jr.

Yet even while the state swings towards the right, Latino voters, 90 percent of whom are Mexican Americans, have remained loyal to the Democratic party. Although Richards lost to Bush in 1994, she received 76 percent of the Latino vote, according to an exit poll by the Southwest Voter Registration Institute. In 1992, Bill Clinton barely lost Texas to George Bush Sr., but he won 71 percent of the Latino vote in the state.

Republican Latinos in Florida

In Florida, a state he also lost narrowly to Bush, Clinton received just 31 percent of the Latino vote — more than was expected. Though the Latino population in Florida is more mixed than in Texas, Cuban Americans, staunchly conservative voters, make up 43 percent. American foreign policy toward Cuba has traditionally kept Cuban American voters loyal to the Republican party.

Swinging Latino Voters

In the past, common perception has depicted Latinos as a small minority with the power in some districts to provide the margin of victory or defeat but without much inclination to exercise their power. The popular misconception is that Latinos don’t vote. But Latinos do vote, says Joseph Torres of Hispanic Magazine — if they’re registered. Although 18.6 million Latinos are eligible to vote, only 5 million are registered. However, most of those registered voters — 82.5 percent — voted in 1992, according to post-election surveys by the United States Census Bureau.

In the presidential election, four of the key states needed for victory contain strong Latino populations. Among them are Texas and Florida (California and New York are the other two), with a total of 57 electoral votes, a sizable chunk of the 270 electoral votes needed to win. The projected population of voting-age Latinos in 1996, according to the Census Bureau, is 3.7 million in Texas and 1.4 million in Florida. In Texas, Latino voters will make up 27 percent of the vote in the 1996 election. Latinos who are eligible to vote in Florida will comprise 13 percent of the state’s population by November. Only 43.6 percent of the 877,000 voting-age Latinos in Florida are registered. Latino voters are the clear majority in Dade County and make up a significant percentage in Orange and Broward counties. If Texas and Florida face close races, the Latino vote could decide the outcome.

— Valerie Menard

Florida — Casting Castro Aside?

There will be no Victor Morales in Florida, but the incentive for Cuban American voters, who make up the largest Latino population in Florida, is American foreign policy in Cuba.

Cuban American voters have voted conservatively since the first mass immigration to the United States in 1959. The reason, said Peter E. Carr, a Cuban refugee and publisher of “The Cuban Index Genealogical Database,” is the single focus on independence and democracy for Cuba. The Democratic Party is perceived as soft on Cuba, whereas the Republican Party has stood hard against any diplomatic relations with the government of Fidel Castro. While Latinos in Texas consistently support the Democratic Party, Latinos in Florida consistently support the Republican Party.

“Cuban Americans have a very long memory, and we still equate Democrats with communist sympathizing,” Carr said. Newer citizens bring recent memories of Cuba that continue the pattern. “New immigrants may seem less vocal, but they have just emerged from an oppressive government, and for the first two to three years, will act as if they’re still in Cuba. This is a similar pattern for all Cuban immigrants,” he said. Second and third generation Cuban Americans also want to see Cuban liberation, if only to visit the country their elders remember.

Clinton moved in the wrong direction mid-term — as far as Cuban-Americans were concerned — when he began to consider easing sanctions against Cuba. In October 1995 he announced that he intended to modify the U.S. embargo on Cuba by relaxing curbs on travel and financial transactions with the island. For anti-Castro Cubans, who wish to travel freely only in a Cuba not led by Castro, maintaining a stranglehold is the key strategy for removing Cuba’s leader.

Clinton also agreed to limit the number of Cuban refugees admitted each year to 20,000. The President refused entry to a mass of Cuban immigrants, forcing them and Haitian refugees to camp for over a year at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. Considered political exiles, Cuban refugees had never been refused entrance to the United States. The President’s action ended a 35-year policy toward Cuban refugees.

However, Clinton seemed to re-establish himself recently with Cuban American voters after taking a harsh stance against Cuba when two civilian planes were shot down by a Cuban MiG-29 fighter jet, killing four Cuban Americans. Operated by a Miami-based exile group, Brothers to the Rescue, the planes regularly flew reconnaissance to search for Cuban rafters. The incident elicited a sharp response from the President: he signed the Helms-Burton Act, which includes some of the toughest sanctions ever declared against Cuba and any person, business, or nation that does business with the country. Cuban-American perceptions of the Democratic party may be shifting.

“Of all the Democratic presidents, Clinton has been the hardest line against Castro, and that may help him do even better with Cuban voters than he did in 1992,” said Carr.

Some Cuban American voters, satisfied that the president has taken a firm enough stance against Cuba, may not vote at all. Though Latino voting rates in Florida were high in the late ’80s, levels dropped in the early ’90s, a trend that may continue in 1996.

Meanwhile other Latino issues, such as immigration, English-only versus bilingual education, and affirmative action may bring Florida’s other Latino voters — Puerto Ricans, Mexican Americans, and Central and South Americans make up a combined 56 percent of Florida’s Latino population — to the polls in new numbers. Republicans, Carr said, have been openly aggressive in their battles with Democrats on these issues. Many Latinos, including Cubans, have looked to Clinton and Democrats in Congress to save programs they support, such as bilingual education, and soften the blow on issues like immigration.

“We hope to see how these issues play out,” said the Democrats’ Hispanic Voter Outreach director Andy Hernandez. Like Carr, he believes that Republican stances against important Latino issues will bring a greater response from Puerto Rican and Mexican American voters in Florida and also will sway some Cubans towards the Democratic party.

Republicans believe they still hold the positions most important in attracting Cuban-American voters. According to Bob Sparks, director of communications with the Florida State Republican Party, the key is to maintain Cuban-American support for the party by implementing a broad-based conservative agenda, focusing on issues including cutting taxes.

Although Bob Dole has taken a hard line on immigration issues, Sparks takes a less staunch approach, acknowledging that in states like Florida and Texas, where the Latino population is large, elected officials must recognize the needs of their constituents. “Representatives Diaz-Balart (R-Florida) and Ross- Lehtinen (R-Florida) have not voted consistently with fellow Republicans on issues like immigration and official English, but we understand that. If they didn’t vote in a way that respects their constituency, they wouldn’t be doing their jobs,” Sparks said.

Because of Latinos’ consistent voting patterns, both parties plan to maintain their usual strategies for the two states: the Democrats hope to hold their 30 percent Latino vote in Florida, and the Republicans hope to hold their 30 percent in Texas. Nevertheless, the Democratic Party seems poised for gains this year. With Victor Morales on the ballot, Texas Latinos will probably go to the polls in greater numbers than they have in the past. But help for Democrats also may come in Florida. Cuban-American voters don’t appear adamantly opposed to the President, and spurred by anti-Latino rhetoric in the Republican Congress, other Latino voters may turn out to vote in record numbers.

Tags

Valerie Menard

Valerie Menard is managing editor of La Prensa, a bilingual weekly in Austin, Texas. (1994)

Valerie Menard is associate editor of Hispanic Magazine in Austin, Texas. (1996)