The Rock Garden

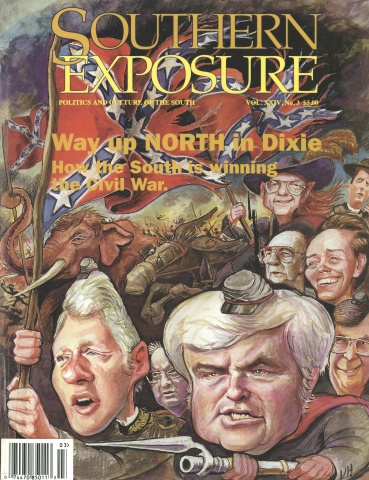

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 3, "Way Up North in Dixie." Find more from that issue here.

My grandmother kills her dogs when she tires of them. She won’t give them away, not even when the vet has found homes. She tells him: “I give my dogs ice water and ice cream in the summertime. I feed them from my plate — pork roast and gravy, cornbread, and butter beans from the garden. They’re used to the best. Nobody will give them as much.” Then she has the vet put them to sleep. Colored Penny died this way, a hunting dog too shy to kill anything herself. And Charlie, whom I called Snake because of the evil look in his varicolored eyes — one blue and one brown. When I visited he’d stalk me, then nip at my calves till I bled. There were more dogs. Leila, my father’s mother, talks of Tuff Enuff, Tiger, and Brandy — but I never met them. They died before I came to the state where my parents were raised. Before I truly knew my family’s families.

I was born in Florida, after my parents fled their small, poor Louisiana towns. They met at the college nearest their homes, my father the first in his family to attend, my mother preceded by her elder sister and followed by her younger. Mother was a senior when my father was a freshman, he having done a stint in the Navy to earn money for school. My father told me the story of their first date a dozen times when I was a child, amending or embellishing as I grew, teaching me what school did not: that history changes with time.

He told me when he arrived on campus some of his fraternity brothers spoke of Ruthie Cook, the “fast” girl who had made the rounds among his new friends. Later, when he was introduced to my mother in the student union, he recognized her name. He asked her out. Come Saturday he rumbled up to her parents’ small house in his sleek black Impala. I imagine my mother’s flush as she spied through the curtains. She was the quiet, bespectacled sister; the one who, nose deep in a book, never heard the call to meals. Her dates were few and with boys who misknotted their ties, knocked heirlooms off the mantel, spoke haltingly of rainfall, soybeans, their various ailments, and family curses.

You would imagine these boys would suit my shy, serious-minded mother, but what no one knew was how as a teen she would creep from the room where her sisters lay sleeping and pore over scandalous novels like Forever Amber and Peyton Place, how in church she would leaf through the Song of Solomon, lingering on phrases like “You have ravished my heart,” “My beloved is like a young stag,” “Your lips drip as the honeycomb.” How she would steal away to the corner store and buy not a cherry limeade but a dime cobalt bottle of Evening in Paris, slipping the scent behind her knees and on the webs of skin between her fingers before school. Or how she memorized the words to “dirty” songs like “Little Pretty One” and “Annie Had a Baby,” humming them softly, daringly, at dinner.

What my mother knows as my father strides up the driveway is that he is worldly; he has flown around the globe on the Navy’s planes. She’s heard that he’s a drinker, a party boy, that he has a tattoo of a little red devil on his bicep. This information, his slick ducktail, and his “shaggy-dog” shoes tell her that he is dangerous, and one ankle wobbles as she hurries to answer his knock.

The way he tells it, my father knew within five minutes that my mother was the “wrong” Ruthie Cook: they would marry in eight short months. Though he didn’t know it yet, my father was tiring of the party life. Often he thought of his advanced age (twenty-five) and his poor grades, and a different kind of restlessness sneaked over him. Soon he would quit the fraternity, make weekly visits to the library where my mother worked, and have her recommend books, which he pretended to read. He would take her to the movies and trail tiny kisses from her fingertips to her shoulder. He would implore her to write his papers, grovel flamboyantly, pretend she had slain him until she agreed. He would sweep her off her sensible feet.

But now they are on their first date, talking stiltedly in the Impala, and they have no place to go. My father intended to find a secluded place to park and let my mother take it from there, but that plan has dissolved under her bright, breathless quizzing (“Do you like to twist?” “This car goes pretty fast, huh?” “Have you ever read Ben Hur?”). It is dead winter, which, in Louisiana, doesn’t mean much, but this winter has been unusual — bitter cold, interminably gray, and there has been a rare and fearsome snowstorm the night before my parents’ date. Driving along the poorly shoveled streets, snow heaped on either side, another idea comes to my father. He suggests they cruise the overpass.

This is not quite as sorry an effort at entertainment as it sounds. The new interstate is a source of excitement in a town with no drive-in, no skating rink, where splitting a malt at the Dairy Dreem is romantic and a trip to Woolworth’s is to die for. The interstate is the world come knocking. It is big town. It is glitz. My mother straightens. “They finished?” she asks. “Just today,” my father says. “So I hear.”

In fact, the overpass wasn’t yet complete — but you’d never know it to look at it. In his telling, my father always pauses here, making me squirm. I itch to take over, tell it for him, add my own details. For I am there, in the seat between them, seeing the clear sieve of sky through the windshield. You would never know, looking at that soft, somnolent dusk, of the previous day’s blast. You’d never imagine that it had forged a brittle bridge of ice over the gap in the road.

My mother is laughing at my father’s jokes as he drives. The heater has made the car cozy, and she adjusts her cat’s-eye glasses, the better to see his perfectly pomaded hair, his crisp checkered shirt, his rolled jeans exposing just the right length of white sock. So charmed is she that she forgets to look up as they climb the ramp, accelerate, and cut a path into air. She is fixed on his shoes as they fall.

It is fully dark when they crawl from the wreckage. The overpass was in fact nearly complete, and they’ve missed the water by a hair. My mother shoves blood and bangs from her eyes as they stagger up the riverbank and weave their way to the nearest porchlight. This is the early ’60s: a time when people open their doors to strangers, when ambulances come quickly — and soon my parents are at the hospital, stitched up and swabbed clean and given shots to sleep. Today, a tiny ridge of flesh cleaves my mother’s right eyebrow, the vestige of her injuries.

“From then on it was all over,” my father tells me. “I’d scarred up your mother so no one else would take her.”

I have looped away from my grandmother, but now I return. And I do return to her every month, making the drive from Baton Rouge to her trailer at the lake. Five hours. A long trip, even risky on the narrow, rutted roads jostling with cane hailers, cotton trucks, pickups that burn oil at forty. I return guessing, as I drive, what will have changed. Sometimes she’ll have new spectacles, sometimes new plants. Once a gleaming pine rocker and a mobile — balsa owls circling placidly at the ceiling. Another visit and the coffee table has been set with her ceramic birds — cardinals, jays, owls, all spaced around a low, wide-lipped bowl. “You see,” she says, splaying her hands at the arrangement. “They come to drink.” Sometimes the change is a dog.

Each visit is strange, full of subtle pressures and hints, food I’m forced to eat much of, Star Search, Christian platitudes, and a dozen small services I’m slated to perform. Sometimes I’ll put up a shower curtain, repot a plant, help pack a box of persimmons from her tree to send my father. But mostly I order items from catalogs — a coal scuttle to hold her magazines, new placemats for fall, a deluxe salad shooter — adding tax and shipping, writing out her check. I make calls to 800 numbers, discovering why the things she ordered without me haven’t come. I scan video catalogs and make recommendations. This was harder in the beginning, when I tried to improve her (“This one is dark, yet uplifting. Are you familiar with film noir?”). Now I know to choose films with small children, dogs or horses (no cats), musical numbers, or men hunting or fishing. We will watch these without comment after Star Search — she rocking calmly, me sobbing helplessly over Old Yeller’s death. Then we are ready for bed. She turns to me: “Want some Advil? Want some Tylenol? Want some Bayer? Want some Excedrin?” After I pop aspirin to please her, we retire. But tonight there is another change. As I head to the spacious side room with the double bed, her sewing machine, and quilting frame, she stops me: “I’ve put you in the other one.” She indicates the closet stuffed with a single bed, the guest room guests never sleep in, the crypt she has claimed every other time I’ve come. As I crawl onto the narrow mattress, I am suddenly unsure. Does this mean that now, at last, she sees me as family? That there’s no need to put on the dog? Or am I again unspecial, unworthy of the best her trailer has to offer? My sleep is troubled, and I wake often to the slow, regular sawing of her snores: I have remembered what is always at the back of my mind when I come — that my grandmother has never loved me.

My mother told me more about my grandmother when I was a teen. She said when my sister was born, Leila came to visit and held Amanda and fed Amanda and rocked Amanda. And when I was born Leila came to visit and held Amanda and fed Amanda and rocked Amanda. Memories from early visits to my grandmother’s house in town came back to me — Leila and Amanda disappearing for hours at a time, returning with bags full of face creams and scented shell-soaps, perfumes and mud masks and those glowing lustrous bath beads. I remember wandering into my sister’s room back at our own house and discovering in her suitcase an owl necklace with glittering emerald eyes, a charm bracelet with little dogs dangling from the chain, a huge faux-amethyst ring that opened like the ones on TV that held poison, only this gem concealed a tiny watch.

During one visit to my grandmother’s they came back from a secret shopping trip with a greasepaint kit, and my sister decided we would be clowns. Leila wielded the paintbrush, and Amanda became a grinning, cherry-cheeked jester. I was given a frowny face, and teardrops fell from my triangular eyes. That afternoon I ran away in the grocery store parking lot, hid between cars, sprinted from row to row while my parents and grandmother circled in the Chevy, calling for me.

After such tantrums my father consoled me in careful ways. “Your grandmother is an odd woman,” he would say. “She has her own way of showing you her love.”

Now my mother asks, “Why do you go see her? She’s never cared about you.” Her question triggers an image of Leila’s old house, the house of my childhood — an inconspicuous brick single story. But in my mind it exudes mystery and glamour. Perhaps it was simply the alien spaces to explore, strange objects to ogle, but as a girl I was devoted to its every detail. In the carport the Cokes were kept in a fridge that Leila opened with a tiny silver key. The frosty bottles fit coldly in our hands like statuettes. Against the wall leaned a dolly over which my sister and I fought bitterly. Usually, because she was older and bigger, she got to play the Sears serviceman, and calling “Hey, delivery! Clear the way! Coming through!” she pushed the dolly up and down the driveway as I, the major appliance, perched stiffly on its jutting metal foot.

In my grandmother’s kitchen a nut dispenser with a little drawer parceled out exotics like cashews, pistachios, and filberts. Caches of mints and candied almonds were secreted throughout the house, mounded temptingly in a porcelain teacup, a little dish into which a hand-painted doe dipped her head. But the piece I returned to was my grandmother’s oil lamp. Gaudy and gold, the size of a stovepipe hat, it perched atop her taboret. This miniature Greek temple was lit by four small bulbs, artfully concealed. Venus posed coyly within its network of tiny wires, down which slipped hundreds of illuminated droplets of mineral oil: the goddess caught in a cloudburst, her tunic clinging to her curves. I thought it beautiful. Wondrous. Of course I wasn’t to touch it; not because it was expensive — the truth — but because, Leila told me, I would urinate unceasingly if I got so much as a drop of oil on my hand. Terrified, I hovered before the lamp each vacation, drawn to its ornateness, its threat. And once, just once, I extended a pinkie into that classical rainstorm, my breathing shallow, my muscles clenched. I waited, a tiny dome of oil trembling on my fingertip, for my punishment. There was nothing, of course, but still I never dared it again. More than to touch it, I wanted to keep the lamp special, dangerous. I wanted to believe my grandmother’s lie.

So when my mother asks, “Why do you go to see her?” I think of how Leila always says she loves me before I hang up the phone, before I drive away at visit’s end. I think about the lamp, and I wonder that each time I make that five-hour trip with shreds of cane and cotton flying off the trucks ahead I am extending a finger to test the truth of my grandmother’s words. I wonder, too, if I want to know it. Or whether I return, month after month, because I want to believe the powerful lie of her love.

In the spartan guest-room bed, listening to the sound of her sleep, I try to guess my grandmother’s thoughts. I imagine her watching as I pull up to the gate and guide my car down the winding drive. The sourdough bread she baked is cooling. Potpourri is simmering on the stove and the bedsheets are fresh and tucked tightly under the mattress. Now she is ready for my arrival. Now she can rest. Yet watching through her eyes as I pull up to the trailer, I feel the imperfection of the moment. I see that the wrong grandchild has returned to her: the sad clown.

I was twenty-four when I learned that my grandfather had killed himself. He died when I was two, and I accepted his loss unquestioningly through my youth, like that of my baby teeth, or my playmates across the street who moved away. I never knew him. He was mentioned rarely, and then with a forced brightness I mistook for cheer.

But at twenty-four, on my parents’ boat during a school vacation, I asked, “Dad, what did Juban die of?” My father stares into the water. My mother, behind him, is warning me with her hands. Finally, my father speaks. “He died of a hard time.”

Juban was a carpenter. At twenty he wed his young love — a farmgirl of sixteen — and built a house for her in the town of Minden. He worked hard at construction and gave her first a boy child, then the finer things: a two-carat diamond ring, a mahogany bedroom set, a fancy oil lamp with Venus posing in a summer storm.

My father had married and moved away by the time the arthritis set in. Soon Juban couldn’t make a fist, and Leila had to wedge forks between his fingers so he could feed himself. She took a job — her first — in the bakery at the Piggly Wiggly while Juban stayed home, eating Bufferin, running scalding water over his hands, trying again to curl his thumb around his hammer.

One morning Leila’s phone rings at work: “Better come quick,” a man says, and the line goes dead. She calls home: no answer. The voice on the phone was her husband’s.

The mystery to me now is not my grandfather’s suicide. He was a good man, a hard worker, shamed beyond bearing by his uselessness, by his failure to provide, by his hands’ unthinkable betrayal. But the abyss stretching between my life and my grandmother’s begins the morning she arrives home from work, having left a tray of unfilled eclairs on the counter. I wonder, as she steps from her car, if she replays her small cruelties in her head, resentment manifest in her staring too pointedly at his fingers, in giving him her shoulder in their bed. For there were certain expectations, I am sure. A horsehair settee, a Hummel or two, a second set of china whose pattern faded in her mind as Juban groaned more often in his sleep. I wonder because I still remember sprinting through that A&P parking lot, my greasepaint tears coming to life on my face. When I tired, at last, and let the car catch me, I faced my Leila tremblingly in the backseat. She cuffed me, as though in play, on the shoulder, but her eyes were aglint with her anger. “You dumb bunny, “she said.

Small cruelties, yes. But all of this — every unloving word or glance, every preferential act, every gift presented my sister on the sly — all this falls away when I turn to that unimaginable morning. I can’t begin to enter the mind of the woman who sheds her past life like a skin as she walks toward the rock garden behind her house. By now the neighbors are gathered, having heard the shot. A dark space yawns open in the yard. In it lies the next moment of my grandmother’s life, the next day, the next year. All the years unformed, unconceived of in her head. I see her standing in the rock garden — the one, I know now, she and Juban spent weekends creating from the stones he unearthed at the construction sites. Great chunks of granite they heaved up onto his truck. I remember it rife with cacti, mother-in-law’s tongue, bromeliads growing gorgeously from cracks in the rocks. The place was peopled with dwarves, knee-high ceramic characters who rolled on their backs or held their bellies in glee, who read upon a mushroom or bent to inspect a ladybug. This is the enchanted garden of my childhood. A very different place from the one my grandmother enters in my third year of life, confronting the hole of her future. She leans against a dwarf that hides its eyes, and it dawns on her that Juban chose the spot with care; she’ll merely have to spray off the stones with the hose. She puts her hands to her mouth and tastes icing.

Now Leila lives in a rattletrap trailer surrounded by sturdy, useful objects, not the delicate ornaments, the graceful, spindly-legged furniture of her previous home. These treasures are in my father’s basement now — in keeping, I was told in a sibling spat when I was ten, for my sister. Leila told her so.

This mattered to me then: the beautiful things, my sister’s triumph. But in college I began to see more clearly, as my sister did when it became clear that she was the only one receiving monthly care packages: boxes brimming with bars of Camay, tubes of Crest, Secret stick deodorants (including one partially used by my grandmother before being tucked in the packing). Carefully my sister would count out equal portions and send me “my half.” Soon, though, I began to scorn her gifts, and when Amanda insisted on sending them, I passed out soap and toothpaste to the girls on my hall — a Robin Hood of good hygiene, enemy of tooth decay.

I was six and banished to my room, awaiting my father’s evening arrival; he was to deal me my punishment. I had taken off my clothes for the neighborhood boys. Twice. And I had twice been found out. The first time I was talked to; now I would be whipped. It was the worst spanking I would ever receive, and as evening approached I began to suspect this. Smaller infractions were met on the spot by my mother with a willow switch — I picked my own from the tree in the yard. But my father was the wielder of a leather belt that he cracked as he came down the hall, the man I waited for in my room, growing wild with the thought of oncoming pain as the hours inched by.

His van drew up to the house at sunset, and I watched from my window as he trudged up the walk. There was muttering from below — my mother sealing my fate. And footfalls — passing my door heavily, leading into the big bedroom down the hall. The next sound I heard was a crack, leather on leather, and in my head the brown loop of my father’s lash doubled in size. He entered the room quietly, still in his suit, the belt draped loosely against his slacks. I was not fooled for a moment by his calm, kindly tone as he spoke of trust, some promise I’d made, how I’d brought more pain to him than he can possibly cause me. I was near blind with terror by the end of his speech. I knew from disobedience past that pleading wouldn’t work, but there had to be a way I could stop the proceeding.

I dropped my pants, laid myself stiffly across his legs, and as he raised his arm, it came to me.

“Dad?” I queried, my voice high and desperate.

“Yes, Nicola.” The arm lowered. He paused, perhaps to hear my apology, to hear me issue another promise, this time one I really really meant.

“If my nose starts to bleed, will you stop?”

Another pause. This was something he hadn’t anticipated, and I felt a pinprick of hope. “Nicola, your nose is not going to bleed,” he assured me.

“Oh,” I said.

He raised the belt once more.

“Dad?”

Now he was exasperated. “Yes, Nicola.”

“But if it does, will you stop?” It was a last-ditch effort, and this time I got the response I wanted.

“All right, Nicola,” he growled, primed now for my punishment. “If your nose starts to bleed, I’ll stop.”

When he raised the belt again, the beating commenced. Though I smarted for days afterward, at the time I hardly felt it. I had balled my hands into fists and begun to pound myself in the face.

The point of the anecdote is merely a certain early perverseness, which extends, in my muddy thinking, to my dealings with my grandmother even now. In college I took my revenge by doling out freely the soap she meant for my sister — slipping bars like boxed chocolates up against dorm-room doors, leaving a fragrant, skin-softening offertory in each of the communal shower stalls. Now I grow trickier yet: I return to her, grow devoted and ever more familiar with her past and person. I return to take her plants out of the greenhouse in the spring, to do her Christmas shopping in the fall. I return to observe the small changes in and about the trailer: a water cooler installed next to the stove, above the sink a clock fashioned from a rolling pin, and two new dogs, Yorkies, who lunge at my face when I sit and fight me in the morning for my jeans.

I return to prove I’m unlike her — kinder, more generous. I return to show her she was wrong about me all along. But whatever the reason for my making another, and yet another trip up that narrow, rutted highway, it’s clear to me that my life became entangled with hers from the first realization that I had somehow missed her love. I once asked my father, after a newly embellished retelling of my parents’ first date, if he would have seen my mother again had they not crashed. His answer was a flat no. But in the course of that short fall to the riverbank, his future and my mother’s were changed. And I see that my grandmother changed mine all those years ago with that slender grease paint brush — that in denying me affection, she drew me closer than her love ever could. And sometimes what comes to mind as I look about the trailer are the things that haven’t changed. The walls display a dozen pictures of my sister. A blond, dimpled child grinning under a huge, floppy hat. A leggy teen with bad glasses posed gawkily before a waterfall. The graduate, one hand on her mortarboard as she hoists a bottle of champagne to her lips. And the bride, eyes dark and depthless as she gazes, not at the camera, but at a rose she lifts to her cheek. There are no pictures of me. And I wonder as we talk of family and Leila sighs and says once again of my sister, “she is just something special,” if in returning to her month after month, year after year, I am simply compounding my grandmother’s early hurt. Suddenly, I am reminded of that long-ago evening I spent across my father’s knees, and I hear again his belt whistling through the air between blows. I received a double punishment that night — one delivered by my father and one I administered myself. He was right: my nose never bled.

Leila married again some ten years after Juban’s death. She met her new husband, Vernon, in church. He courted her by inviting her along on fishing trips, teaching her to play Solitaire, letting her iron his shirts. Now, sitting over our steaming coffee, she tells me, “I knew it was a mistake the minute I said, ‘I do.’” They are mortal enemies, she and Vernon. But he has an Army pension, and she cleans the trailer and tends the garden, so they stay together in separate rooms, not speaking.

Most visits she won’t let me eat with him. “Let’s wait,” she says, “till that old goat goes to bed.” She heats a can of Beanie Weenies in the microwave, peels a slice of Sunbeam from the loaf for him to sop up the oily orange sauce, and cuts a raw green onion. All this she drops on a dirty paper plate — the one he ate from the day before and the day before that. This is Leila’s revenge for his complaint of her wastefulness: she is ever throwing “perfectly good” things away. After he has finished his meal and shambled back to his room, Leila wipes his warped orange plate with a paper towel and stores it under the sink. “Sometimes,” she says, “I could just maul his head.” I choke on my soda, and she interprets this as a rebuke. “I ask the Lord to forgive me when I say things like that,” she says. “And I think he does.”

Then she pulls our feast from the oven: eye of round, black-eyed peas, cole slaw, corn salad, and her made-from-scratch cornbread. Tomorrow, if she feels God is watching, she will give Vernon our leftovers. If God sleeps, they’ll be fed to the dogs.

Vernon will read his Bible while I’m there, hunch over it all afternoon in his chair at the edge of the carport, smoking his pipe. Sometimes he’ll shoot a squirrel out of the pear tree, or knock the fruit from the bowed branches to prevent them from breaking. Before the stroke, he’d have three scotch-and-waters before noon. Before the stroke, he’d be fishing. Now he’s afraid to go out on the water alone.

Leila wouldn’t let me visit after it happened. “It’s too bad here,” was all she’d say. Later, after his recovery, she told me how bad. Out of his head, he wouldn’t sit still, and she followed him around the trailer, plucking plates and lamps from his hands before he would hurl them at the walls. I mention this month, which is sunken and flappy, like a punctured tire. “He kept throwing his durn dentures away,” she says. “I dug them out of the trash a hundred times. Then I got tired and let them stay there. He’s trying to get the Army to pay for new teeth.”

As she speaks she fishes twelve white raisins from a jar full of gin and lines them up like a corps of cadets on the napkin before her. Then she eats them one by one. These are her miracle cure. Last year she couldn’t walk twenty yards, couldn’t quilt or lift a frying pan above her waist. She had physical therapy twice a week and cortisone shots in her joints, to no avail. Then a friend from church revealed the secret of the raisins — twelve each morning, only the white kind, only gin — and now she moves easily, stooping to hide the jar behind the washer so Vernon won’t drink the juice. “He found it once,” Leila tells me, “and left the raisins high and dry. I didn’t have to look to know it. He was nasty as a crow all day.” I leave this last remark a mystery, for Vernon is sweet to me in his way, presenting me with gifts each visit: a rusty bottle opener for my keychain, the Old Salt’s Book of Poetry (from which he recites a few bouncing couplets), a saltine-sized New Testament passed out in his Sunday school, a jug of antifreeze. I ask Leila whether his children ever visit. She flicks out her tongue and withdraws it, snake-quick. “They won’t mess with that old fool,” she says.

“Why not?” I ask.

She looks at me piercingly. “Well, he’s had nine wives.”

I choke, I cough, I wheeze to cover the incredulous laugh that has caught in my throat. “That can’t possibly be true!” I exclaim at last.

“Well, you know he was in the Army,” she says in a tone that means this explains everything. Then she backtracks, worried perhaps that she has gone too far. “Now don’t tell anybody what I said,” she warns me, “because I am ashamed of that.”

This is how I know she has lied. But by now it doesn’t matter: I am delighted, completely taken with her. Her guile has its benefits, and my constant surprise is one of these. Her deception is a flute song, and I am charmed. I will return and return again, if only to discover how she will change her story. Next time he could be a quintuplet, a Nazi war prisoner, a royalty dethroned. I want to be witness to all this incarnations. And to hers.

Leila’s father was the son of an Irish immigrant. He was fire-haired, small-boned, and feisty. He could tear you apart with his tongue. My father grins when he speaks of his Grandpa Selden: “He was the cock of the walk, lord and king, and he’d as soon spit as look at you.”

Once, when my father was on leave from the Navy, Leila drove him to her parents’ for Sunday supper. The whole family was gathered, as was the custom on Sundays — twenty-odd farm people milling around the yard along with sun-dark kids wearing blunt, sewing-scissor haircuts. Presiding over all was Selden, strutting from group to group, half the size of his sons but with twice their stature, back-slapping or rocking on his heels or raising a finger as though to test the air — all the while holding forth in his high, tinny voice.

When he reached my father he grew silent, eyeing him from loafers to crewcut, a twist of his lips signaling distaste. His gaze had fixed on my father’s chin. Grown lazy on his leave, my father hadn’t shaved. Selden puffed up like a blowfish, his temples pulsing, his shoulders growing sharp as he filled his chest with air. “See you’ve got some baby hair,” he said, calmly fingering his own day’s growth.

My father, full of brash, military confidence, accepted the challenge. “It’ll take your skin off,” he said.

In a trice the two faced off, digging their heels into the ground and shaking the kinks out of their arms. There was an instant of dead staring. Then they lunged, locking arms, and slapped their cheeks together and began to scrub furiously — chin against chin. The family looked on as the seconds drew out, the one sound the sandpaper rasp of whiskers at war. At last Selden flung himself from my father’s grasp, his jaw the color of flame. “That’s no beard, that’s barbed wire!” he pronounced, stalking off to cool his face in a rainbarrel. My father grins madly when he recounts his triumph. He calls this the happiest day of his life.

In the evenings Leila and I tour the yard. It is cool then, and ducks have come up from the water to beg for the corn that rains from our pockets. Bald cypresses spear into the sky, made gauzy by mantillas of Spanish moss, and dense islets of water hyacinths pool at their feet as though a cloak had slipped from their shoulders. Hummingbirds brush by our shoulders. There are dozens of them, and a score of ruby feeders sway in the trees. In midsummer Leila will fill them every day, and as I draw close to the pepper tree, the soft, electric sound of their wings will come to my ear. The sun lowers over the lake. Leila clutches my arm as we walk so as not to stumble in the lessening light, and I am suddenly aware of her stiff walk, her dimming eyes, and my taut shoulder under the mottled crab of her hand. And I know that this too is part of it — the reason I return. That in some sense a contest is being waged, one whose stakes are the past. It is one I must feel I am winning, or I would not keep coming back. But it is not triumph I feel as we wander past the rock garden, transported stone by stone from the house in town years ago. It’s a certain expectancy that holds me here now. And I think again of the lesson in my parents’ first date: history changes with time. I think of my grandmother’s dogs. I believe she truly loved them. And here lies possibility: if she can end a love, it follows that she can begin one. The expectancy that someday I will roll down that drive and the change that I see will be me.

Tags

Nicola Mason

Nicola Mason is assistant editor of The Southern Review and has fiction forthcoming in New Virginia Review. (1996)