This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 3, "Way Up North in Dixie." Find more from that issue here.

Picture me composing this essay.

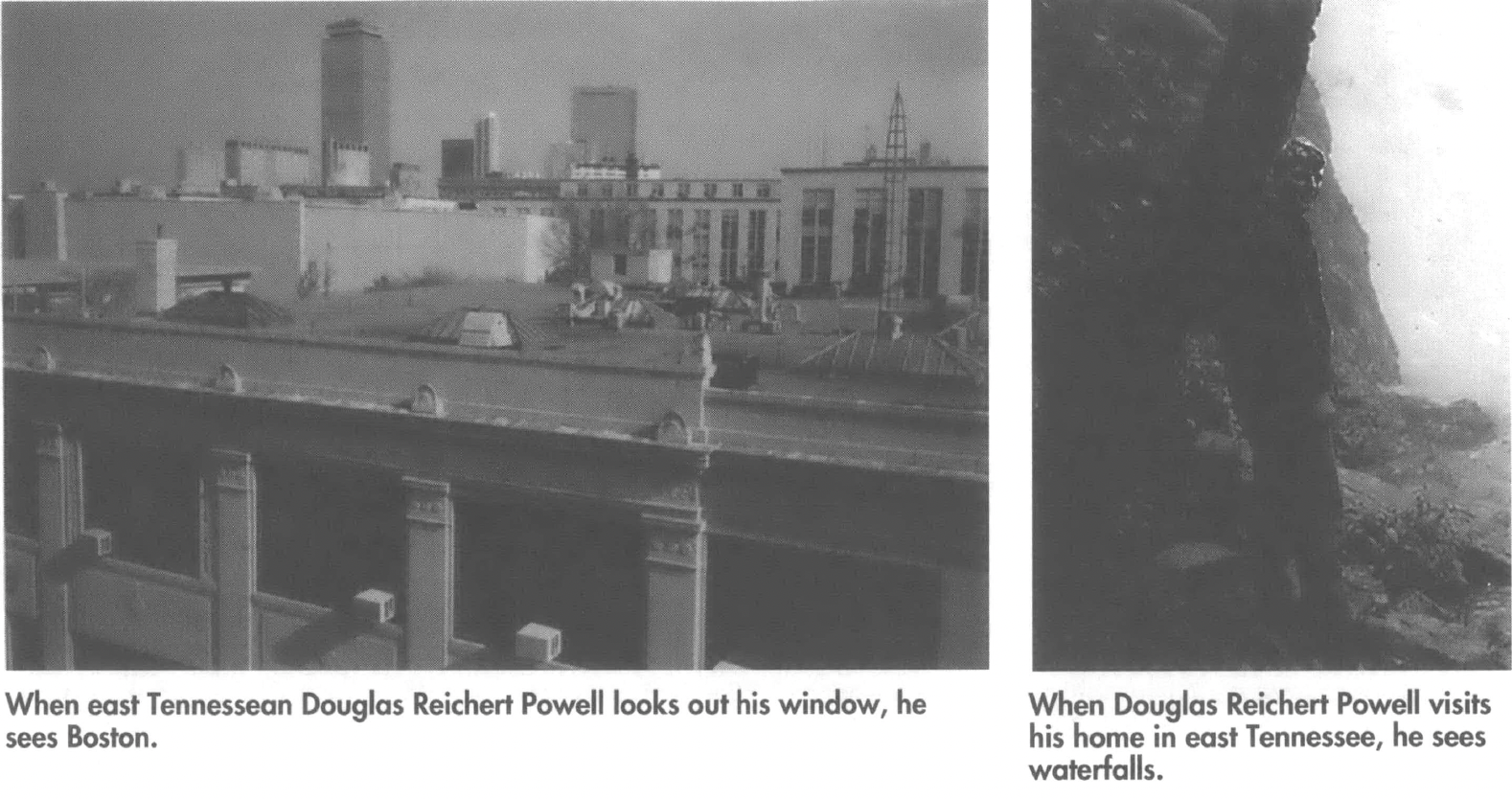

I am sitting at a desk, facing a computer screen, wearing a flannel shirt and a baseball cap. Behind me, a window frames a slice of the Boston skyline, the Prudential and John Hancock towers dominating the landscape. On the wall above me a series of maps is folded, thumb-tacked, and taped together to become one map of part of east Tennessee, including the Johnson City, Jonesborough, Unicoi, Erwin, Elizabethton, and Iron Mountain Gap quadrangles mapped by the U.S. Geographical Survey.

What’s wrong with this picture?

You might say I shouldn’t have my cap on indoors. Or you might say it’s odd to be writing about Appalachia in central Boston. That second remark is more to the point here. It raises the question of where Appalachia is, exactly. Clearly, it’s not out among the tall buildings, but how do we know that? How do we know what Appalachia is not? And even if we recognize the landscape as Not Appalachia, we still have to answer the question, where is Appalachia? Is it on the map? Is it in me?

For most of the people I know around Boston, the answer would be that Appalachia is in me. For most of them, I am their only experience of Appalachia, so I represent an entire region — people, practices, landscape, and all. Appalachia is in me in the same sense that Israel as a nation includes the Diaspora. And when people remark on my Southern-ness, I often correct them: “Appalachian, actually.” I invariably add that I’m from east Tennessee.

The place from which I emerged is with me still. Origins play a major part in my sense of self; the past shapes my definition of the present. Appalachia moves with me among the tall buildings and has a foothold in an overpriced apartment a few blocks from Fenway Park — an apartment that costs more than the entire house and 40 acres where I lived before moving here from a small black dot in the upper-righthand corner of the Erwin quadrangle in east Tennessee.

However, I’m not willing to commit to the concept of Appalachia as some kind of metaphysical quality. My affiliation with Appalachia has more to do with a conscious, willful set of actions — not to mention an element of artifice — especially in this setting where “Appalachian-ness” is a foreign, almost exotic trait. Appalachia is something I can do, like wear a ball cap or say “fixin’ to” and it’s acts I’m conscious of performing. In fact, last Halloween all I did was put on something I might have worn on any given day on that 40-acre farm: camouflage pants, a flannel shirt, and a cap with a chain saw logo. I billed this as my native dress. This is a performance model of Appalachia.

Or you might say that I’m not in Appalachia at all. Appalachia is a place, a geographical reality on the map. Sure, Appalachia is in me, but I’m not in Appalachia. This geographical model postulates a very different model of cultural identity, tying the region exclusively to the land. It suggests that it’s futile to ruminate over what, exactly, region is. A region is a place, and a place is a body of land. Either you are in it, or you’re not.

I have a bias toward the performance model because I’m not “in” Appalachia, and I’d like to preserve something of that identity for all kinds of reasons, not all of which are clear even to myself. Still, when pushed to the logical extreme, both models have problems that point toward a larger underlying difficulty in trying to create any closed cultural model.

You Can’t Get There from Here

The performance model, that Appalachia is something you do, is illustrated by Stephen Greenblatt in his introduction to Marvelous Possessions. On his first night in Bali in 1986, Greenblatt saw a light in the communal pavilion, which was where his anthropological reading had taught him the Balinese gathered in the evening:

“I drew near and discovered that the light came from a television set that the villagers, squatting or sitting cross-legged, were intent on watching. Conquering my disappointment, I accepted the gestured invitation to climb onto the platform and see the show: on the communal VCR, they were watching a tape of an elaborate temple ceremony.”

This scenario — highly reminiscent of the popular stereotype of the hillbilly shack with the satellite dish out back — illustrates a problem with the idea of culture as a stable and inherited set of beliefs and practices. One feels that the Balinese should be watching the ceremony in person and that the VCR and television pollute “real” Balinese culture. This view places inordinate emphasis on preserving “authentic” ways, suggesting that inherited practices should occur only along sanctioned and existing lines.

Greenblatt writes: “I think it is important to resist what we may call an a priori ideological determinism, that is, [the view] that particular modes of representation are inherently and necessarily bound to a given culture or class or belief system.” Greenblatt casts his discussion in terms of ideology. An approach to Appalachian culture that defines the region as a set of practices or designates a particular practice as the exclusive domain of a people is highly questionable. Such a methodology can be easily co-opted into the service of racist or otherwise discriminatory politics. Moreover, even done with the best of intentions, the argument about authenticity is fraught with dangers. If decisions are to be made as to what is authentic and what is not, who is entitled to make such decisions?

Greenblatt based his expectations of Balinese culture in part on academic writing. At first, he felt that it was the culture, not the studies, that needed correcting when his experience ran up against his expectations. This disjuncture limits the possibility for expansion, assimilation, and transformation of a culture even as the viewer attempts (or pretends) to protect, privilege, or honor the culture. The defense of “authentic” cultural practices includes a potential paternalism that denies the constant dynamics of transformation, instead nostalgically valuing “old ways.”

Museums physically manifest this approach to culture. The museum is the grammar of the metalanguage of colonialism. In Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Benedict Anderson discusses the ways in which colonialists in southeast Asia systematically “reconstructed” ancient cultural sites — Angkor Wat in Kampuchea, Borobudur in Indonesia — draining them of their cultural value. It’s not difficult to see these same processes at work in the Great Smoky Mountains, giving us, for example, the meticulously authentic but now almost empty — save for tourists — Cades Cove.

In Appalachia, Anderson’s archeology assumes the form of the living history museum, which is a subclass of the theme park. Colonial archeologists subverted Native Americans’ connections to their heritage by subjecting it to scientific scrutiny and then reconstructing it in ways that placed it irretrievably distant in history. So, too, heritage parks and preservation efforts sever contemporary Appalachia from its past.

Historic theme parks sunder us from an organic harmony, and they reconstruct history in strangely alienating terms. This lost order survives only in the form of commodities, in marketable wares that have replaced the complex dynamic of lived experience. Anderson calls this “logoization,” the conversion of culture into uncomplicated emblems: unpeopled postcards of Angkor Wat that allege to be the experience of Kampuchea. Similarly, in The Culture of Nature, Alexander Wilson catalogues the “hillbilly gewgaws” in Gatlinburg, Tennessee: “carved wood figurines, plastic flowers, Dolly Parton T-shirts, whiskey-still charm bracelets, Christian inspirational plaques, and fake folk medicines.” The character of any logo, writes Anderson, is distinguished by “its emptiness, contextlessness, visual memorableness, and infinite reproducibility.”

Mapped by TVA

When one nails down exactly what artifacts are at the heart of a culture, one is ready for the trip from Cades Cove to Dollywood. Ultimately these sanctuaries of “authenticity” are of the same genus if not the same species as industrial parks, shopping centers, and suburbs.

The emphasis that theme parks place on the geographical aspect of a culture points to the problem with the commonsense approach of defining a region as land with physical boundaries. It may seem simpler to say that culture is tied to a place, but the implications of this geographical model fragment fairly quickly, just as happened with the model of defining culture in terms of practices.

In his Death and Dying in Central Appalachia: Changing Attitudes and Practices, James Crissman suggests the fluctuating nature of a geographical conception of Appalachia. But it’s surprising that Crissman then comfortably and fairly arbitrarily defines Central Appalachia as “the Appalachian sections of Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, Kentucky (including the northeastern and southeastern part extending into the foothills), and the entire state of West Virginia.” Granted, Crissman’s aim is to document funerary practices, not define the region. Still, the way he draws the map is another example of a deterministic approach to culture.

As Benedict Anderson observes, if the museum objectifies cultural practice, the map objectifies the space a culture occupies. A Tennessee-shaped magnet from any of the many Dollywood gift shops illustrates how easily the state’s outline lends itself to logoization. The cartographic definition of region is like the colonialist museum, not by distancing but by denying the past. Maps exist in an eternal present. Even when the traveler’s experience of the landscape is at odds with the depiction, maps contain within themselves an argument for their own completeness and accuracy.

Indeed, geography and cartography historically reflect political positions, all the while denying the alliance through scientific or legalistic rhetoric. To use a map is to acquiesce to its authority, as if maps were transparent windows, authorless anomalies in the textual universe. Yet behind this illusion lies immense authorial power: the power to write the very face of the earth.

The maps on my wall show the many layers of authorship these artifacts involve. These wonderfully detailed maps have been of great use to me not only as an outdoorsman on my native ground but also as an evocation, far from home, of the places I love to spend my time: Laurel Falls, Red Fork Falls, Big Rock, Zep Spot. Above all, however, these are government maps, and they are almost eerie in their detached, omnipotent gaze that converts the very contours of the land into data.

The way a map “looks” at the land necessarily depopulates it. In their pretense to timelessness, maps are methodologically incapable of accounting for the movements, activities, and lived experiences of real people. All that remains are opaque representations of cultures, black dots that stand in for complicated lives.

In this context, “U.S. Geological Survey” written on the map has an unsettling and regimented ring to it. What’s more, as the fine print notes, these particular quadrangles were “Mapped by the Tennessee Valley Authority.” It is oddly appropriate that the government agency that arguably has had the greatest role in rewriting not only the contours of the culture but the shape of the landscape itself is the agency that has the authorial and authoritative task of describing the land.

The ways in which the TVA has gone about representing its “beneficiaries” bear closer scrutiny. The methods suggest that the operations of government on the American interior are potentially as insidious as the colonial conquests of cultures outside our national borders. This can be seen in the series of photographs commissioned by the agency of homesteads on reservation sites, seemingly designed to show their squalor (a potent version of “authenticity”), or in pro-government propaganda such as former TVA official Arthur Morgan’s book The Making of the TVA, which includes some of these very photographs.

My maps, though, seem to resonate most deeply with a distant, depersonalized view of Appalachia, a view TVA uses to harness the region’s resources into a modern power grid. In her poem “The Map,” Elizabeth Bishop writes that “mapped waters are more quiet than the land is.” Her remark captures the irony of those cool, uniformly blue expanses on, say, the Boone Dam or Watauga Dam quadrangles. Beneath those waters dammed by the TVA are homesteads and graveyards and trails and valleys and hills that the map will not admit as a past or present reality.

Identity Crisis

Ultimately, maps and heritage museums work in roughly the same way. In their quest to contain culture in an artificial, finite zone, they make it available for unethical uses: stereotyping, exploitation, commodification. But like any culture, Appalachian culture is infinitely more complex than any model could possibly take into account. It is with some pride that I look at the county-by-county map in the front cover of Paul Salstrom’s Appalachia’s Path to Dependency to discover that, as a native of Washington County, Tennessee, I am from “Older Appalachia.” Is this the solution to my identity crisis? But what would Salstrom think if he knew that there, in the heart of Older Appalachia, I grew up in a notably un-rustic neighborhood of university professors known informally as Scholar Holler? Or that my experience of Appalachia centers on a medium-sized city, that the only times I’ve been around looms or churns or bull-tongue plows were in heritage museums and the households of collectors? Is my experience of the region I claim as my birthplace rendered inauthentic by my place within the culture?

Here at last the performance and geographic models of culture lock in conflict. It’s not me or my culture that’s gone wrong, been conquered, disappeared — it’s that all the available models of the culture I grew up in are too static to take into account the changes wrought in Appalachia over the years. What’s more, there never has been a time of Edenic exemption from the processes of cultural change and evolution in Appalachia or in any region, no moment of cultural purity. As the British scholar Raymond Williams notes in The Country and the City, every generation mourns the recent demise of the pastoral ideal and the disappearance of the older, simpler ways.

Indeed, warning bells of potential manipulation and intellectual peril should sound whenever representations of a culture seem to validate in absolute terms the clear outlines of its existence. To the extent that the academic field of Appalachian studies attempts to intervene on behalf of Appalachian culture, whatever it may be, and to benefit the lives of these people, whoever and wherever they are, the map and the heritage museum and the paradigms they represent are a Scylla and Charybdis. To be a vital space for public discussion, Appalachian studies must, I believe, avoid a narrow conception of its objects or locations of study. Instead, it might open lines of dialogue with other cultures and other criticisms. For all that is wonderfully unique about the region, much can be shared with the experiences of other culture — Indonesia and Cambodia, for example. Much can be gamed from alliances with other socially and politically conscious areas of cultural studies.

It might seem ironic that despite all these misgivings about attempting to contain culture, nonetheless I use the word “culture” throughout this essay. There is a regional culture, and we are in it now, and I am in it in the picture of myself that opens this essay. The regional culture, the Appalachia that I espouse, is historic but dynamic throughout its history, open to incursions and excursions, living in the present but cognizant of potential futures and the range of versions of the past.

Culture is the result, not the source of, our discussions and experiences of region, and our memories and articulations of those memories, and our plans and concerns about what is to come. Culture is inheritance, but it is also frays in patterns of inheritance, the intrusion of the new and the systematic distortion of the old. To be Appalachian is to participate, whether on location or from afar, in the acts, words, deeds, and landscapes of our ongoing debate over who are the “Appalachians.” The region exists, securely, as long as the debate goes on.

Tags

Douglas Reichert Powell

Douglas Reichert Powell is a doctoral student in English at Northeastern University. He also attended Washington and Lee University (BA, 1990) and East Tennessee State University (M.A, 1992) and is associate editor of the anthology, Appalachia Inside Out (University of Tennessee Press, 1995). (1996)