This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 3, "Way Up North in Dixie." Find more from that issue here.

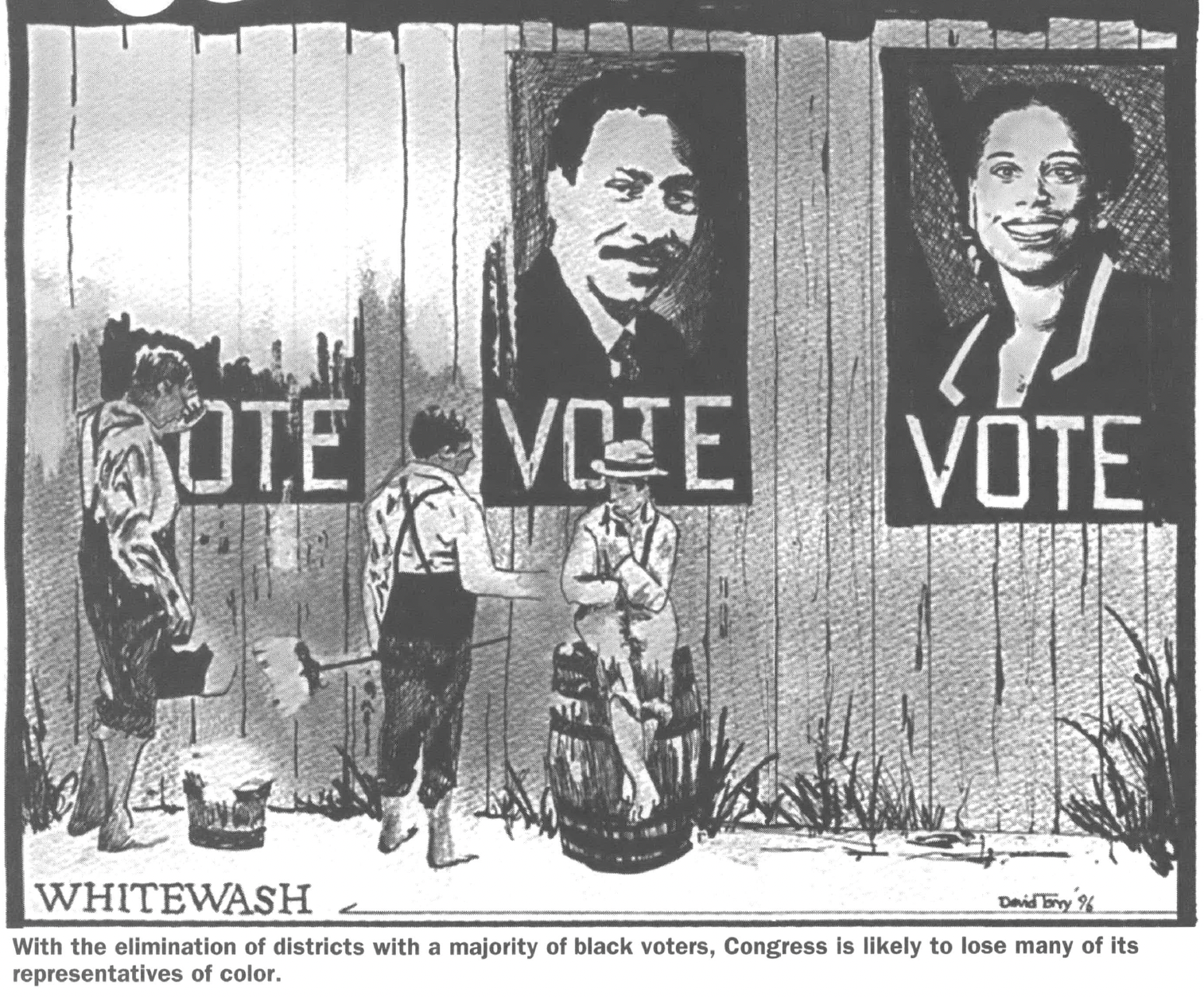

This November, if the U.S. House of Representatives becomes a whiter institution, some of the responsibility will belong to a small group of conservative political activists based in Houston. Since 1993, the Campaign for a Color-Blind America has been successfully challenging voting districts created to increase minority representation in Congress and state legislatures.

The Campaign was formed in the wake of Shaw v. Reno, the 1993 North Carolina case in which the U.S. Supreme Court rejected as “bizarre” the lines drawn for the majority black 12th district of Democratic Representative Melvin Watt. His district snakes from Charlotte to Durham, in some places only the width of Interstate 85. To comply with an amendment to the Voting Rights Act, state legislatures created 10 new “majority-minority” congressional districts in the South — districts with a majority of minority voters — after the 1990 census. The number of African American congressional representatives jumped from five to 17 after the 1992 elections.

After the Shaw v. Reno ruling overturned North Carolina’s 12th congressional district, several Houston-area Republicans filed similar lawsuits contesting Texas congressional districts. The federal court threw out three majority-minority districts in Texas, and the fledgling Campaign for a Color-Blind America had won its first major battle. On appeal of the case, Vera v. Bush, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Texas lower court decision in Vera v. Richards.

This November in Louisiana, Georgia (which also had its districts overturned this year), and Texas, minority incumbents are fighting for their political lives in districts redrawn after similar lawsuits. North Carolina’s 12th district will be redrawn for the 1998 election. Similar cases are pending in Virginia, New York, and other states.

Damned Ironies

In Texas, Edward Blum, chairman of the Campaign for a Color-Blind America, is among the group of Republican plaintiffs who negotiated with the state for a new Texas congressional map. “But you’d think that I had dropped some kind of a biological weapon on the Texas delegation in D.C.,” said Blum.

The Campaign, a legal defense and educational foundation, is dedicated to eliminating racial distinctions in American political life — whether those distinctions are used to empower or disempower particular groups of citizens, said Blum. He describes the Campaign as “a loose, ad hoc group of primarily legal scholars, social scientists, and people who’ve been active in the civil rights movement that communicate with one another about issues of racial gerrymandering.”

Blum, who is white, said that contesting the consideration of race in drawing district lines carries on the tradition of the civil rights movement. “You cannot classify people by race and segregate people by race for something beneficial,” he said. “You have defeated — this is my philosophy — you have defeated the entire depth of the civil rights movement.”

Blum seems unfazed that representatives of that movement almost universally disagree with him. Houston attorney Charles Drayden, for example, who has fought Blum’s organization in court on behalf of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, is skeptical of Blum’s claim to a civil rights rationale for his attack on majority-minority districts. “I don’t think Edward Blum is a person who’s qualified to carry on that struggle,” said Drayden. “He hasn’t solicited the assistance or any of the ideas of any of the people who might have suffered from those kinds of distinctions in the past, but he has decided that he and his cohorts [in the Campaign] are the only ones who have any kind of ideas as to what is right when redressing racial distinctions in American politics. I think that is a very arrogant notion.”

Blum’s notions, arrogant or otherwise, are gaining credibility in one important place — U.S. courts have been increasingly sympathetic to arguments that considerations of race in redistricting are legally suspect, if not inherently unconstitutional.

In Texas, for example, the 1994 Campaign lawsuit charged that 24 Texas districts had been created through illegal racial gerrymandering. The three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court ruled in favor of Blum and his fellow plaintiffs, but only in reference to three majority-minority districts: Blum’s own 18th district and two others, Houston’s 29th and the Dallas-area 30th. The court ruled that the three districts “were scientifically designed to muster a minimum percentage of the favored minority or ethnic group; minority numbers are virtually all that mattered in the shape of those districts. Those districts consequently bear the odious imprint of racial apartheid, and districts that intermesh with them are necessarily racially tainted.”

In a 5 to 4 decision in June, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the district court decision, ordering the Texas districts to be redrawn because race had been the “predominant” factor in defining the district boundaries.

For most minority advocates, the accusation of “racial apartheid” by the lower court judges (three Republican appointees) was particularly insulting. Laughlin McDonald, director of the Voting Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union, told the National Law Journal, “Anyone who knows what apartheid is could never confuse racial redistricting with apartheid. To suggest that this is what racial redistricting is all about is dishonest.”

But to Blum and his group, racial gerrymandering, however benignly intended, is a form of apartheid, and he reiterates his belief that “the use of race or ethnicity or religion in our public life is inherently immoral. That’s the base that I was taught, and that’s the base that I believe, and that’s the base the NAACP used, leading up to Brown v. Board of Education. That the Constitution is colorblind is our dedicated belief.”

Blum, who said his parents were active in the civil rights movement, is fond of citing the late Supreme Court justice and civil rights pioneer Thurgood Marshall in defense of his “color-blind” argument. But at Houston’s Thurgood Marshall School of Law, there is considerable skepticism about Blum’s claim to Marshall’s civil rights mantle. Professor Carroll Robinson of the Houston Lawyer’s Association, a group of African-American attorneys, finds Blum’s claim to a civil rights heritage “damned ironic.

“It’s ironic,” said Robinson, “that majority white districts, congressional districts, all these years, have never been viewed as a violation of the Equal Protection Rights of African Americans, Hispanics, or Asians, and all of a sudden, the court and some minute group of whites, have suddenly found the need to say that the privilege they’ve enjoyed all these years is somehow being ripped from their clutches — simply because now we’re being given the chance to elect representatives of our own choice.”

Fine Cuts

Blum said the seed for his organization came from his own failed 1992 congressional campaign against African-American incumbent Craig Washington. With little support from the Texas Republican party, which, Blum said, didn’t want to waste resources on a “black district” like the 18th, he spent $100,000 of his own money, and he and his wife ran a door-to-door campaign. Walking throughout the widely scattered district neighborhoods, he said, he discovered the “racial gerrymandering” that would inspire his personal crusade. Confusing district lines, he said, far too often cut through neighborhoods, along streets, or between tract homes and apartment houses — and, to Blum, the visible distinction was race. “The cuts were so fine,” he said, “that they often split the streets down the middle.”

Defenders of the district lines insist that apparent racial distinctions also often indicate traditional party preferences, which is considered a legitimate factor in drawing boundaries, but Blum remains unpersuaded. He said his run against Representative Washington was motivated by political idealism, and that Washington was so “universally disliked” that Blum found much support for his quixotic campaign.

“I spent a year of my life and $100,000 of my own money,” said Blum, “knowing that if I had won that election, it would have been the show-stopper congressional election of the decade: ‘White Jewish conservative defeats black liberal incumbent in wildly Democratic district.’ You’ve got to have a big streak of idealism to do that.”

Idealism was not quite enough. Washington defeated Blum handily, although Blum’s 33 percent of the vote was a full 11 percent better than President George Bush garnered. In the 1994 congressional election, Washington lost to another African-American candidate, Houston city councilwoman Sheila Jackson Lee.

Blum said it was also his idealism, and that of six other Texas Republicans, that motivated his lawsuit against Texas districts following the 1993 Supreme Court decision rejecting North Carolina’s majority-minority districts. Blum gathered potential plaintiffs for a Texas challenge and asked William Bradford Reynolds, formerly of the Reagan Justice Department, to take the case. Reynolds asked for a $200,000 retainer, “an enormous percentage of my net worth,” said Blum, who makes his living selling municipal bonds. Blum decided to follow the “civil rights model” and recruited like-minded attorneys to work pro bono.

He asked the experts. Duke University law professor Robinson Everett had argued Shaw v. Reno before the U.S. Supreme Court. Louisiana attorney Paul Hurd had argued similar challenges in Louisiana and Florida. Blum recruited them and Houstonians Ted Hirtz, Doug Markham, and others. They volunteered most of their time and expenses in the expectation that should they win, their fees would be paid by the governmental defendants in each jurisdiction. That, said Blum, is what he meant when he told a reporter that the Campaign was willing to invest “a million to a million-and-a-half dollars” in any lawsuit in which it chose to take part. His comment was published widely.

Blum said the group’s expenses thus far have largely been confined to smaller, short-term matters — costs directly out of pocket, such as document duplication or travel — and that he has generally paid them himself. “We have spent a little bit of money. It wouldn’t buy you a new car,” he said.

“The question came,” Blum said, “how much did these lawsuits cost? OK — the lawsuits, every congressional redistricting lawsuit I know of argued through the Supreme Court — has cost the state well over a million dollars. Everybody reads this and thinks, ‘Adolph Coors [of the Coors Beer family] and all the right-wing cranks have sent millions of dollars to defeat these districts.’ That’s not true; that’s not at all the case. We have been able to raise $25 to $30,000. That’s all public information: legal fees, travel expenses, some of these outstanding bills. All [the cases] have been argued pro bono and contingency.” Contingency means that attorneys would collect fees from the states if they successfully argue their cases against redistricting. The fees can range from a half million to a million dollars, according to New Journal and Guide in Norfolk, Virginia.

The fees have benefited Campaign for a Color-Blind America board members, including Charles Bullock and Ronald Weber, who collect fees for serving as expert witnesses in redistricting cases. Both have set up consulting firms to provide experts for attorneys fighting redistricting. Another board member, Daniel Troy, has collected attorney’s fees from the state of Texas for the Vera v. Bush case (see sidebar).

Nonpartisan

After the victory in Vera v. Richards, Blum began receiving nationwide inquiries and requests for help. The Campaign was incorporated as a nonprofit legal foundation and has provided networking for legal assistance and information to groups from New York to Hawaii. He and his wife, Lark Blum, run the organization out of their Houston home, primarily by recruiting lawyers and expert witnesses to share information and provide assistance to groups challenging voting districts.

Despite his own background in Republican party politics and the presence on the board of directors of Republican partisans Linda Chavez (see sidebar), director of the Equal Employment and Opportunity Commission in the Reagan administration, and Paul Weyrich of the rightwing Free Congress Foundation and National Empowerment Television, Blum said the Campaign is non-partisan. He said that the Campaign has upset Republican politicians as often as Democrats because Republicans under George Bush’s presidency championed majority-minority districts. Both parties’ attitudes on the issue are “cynical and disingenuous,” said Blum.

Blum is not alone in his assessment. Some Republicans, especially in North Carolina and Georgia, have argued that while the 1994 redistricted elections resulted in doubling the number of minority representatives in Congress, they also helped Republican candidates win elections in neighboring “bleached-out” districts. Sociologist Chandler Davidson of Rice University said that some liberal Democrats have loudly criticized the redistricting for the same reason — that it results in the election of more minority members, but at the cost of leaving them politically isolated.

Davidson said that given recent history, returning to supposedly color-blind methods is unrealistic and mistaken. “There is a trade-off,” Davidson said. “Given how difficult it is for blacks to win elections from majority white constituencies, you’ve got a choice between not drawing districts in which blacks can win anymore, and, on the other hand, increasing the numbers of Democrats in Congress, if only by a few seats. Admittedly, that’s a difficult trade-off. Yet it’s rather presumptuous, or rather flippant, for people to say, ‘Well, it’s obvious that we ought to have fewer blacks.’

“The most strident in criticizing these districts nowadays are white Democrats, liberals and moderates, who say either up front or between the lines, ‘Look, whites can represent blacks at least as well as blacks can themselves and maybe better. And in any case it’s going to increase the numbers of Democratic votes, and that’s more important than having a black face in Congress.’”

North Carolina Democrat Melvin Watt, whose 12th district was ordered redrawn by the Supreme Court, emphatically rejects the argument that majority-minority districts isolate black voters and elect more Republicans. “It’s an erroneous argument,” said Watt, “In North Carolina, that [racial redistricting] should have created a substantial Republican shift in 1992. It didn’t happen. We went from seven Democrats to eight in 1992.”

When the dramatic Republican shift came, Watt said, it was in the 1994 election, and it occurred also in states not subject to racial redistricting. “In Washington state, there are no minority districts, and it had the most dramatic shift toward Republicans of any state in the union. The truth of the matter is that the black community gets blamed for a lot of stuff that we don’t have a damn thing to do with.”

Watt said that in any case, black voters are not necessarily better represented by white Democrats. “It’s all based on the proposition that the minority community is better off in an ‘influence’ district than in selecting the representative of its choice,” he said. “Look at some of the districts in the South, where historically there have been 30 percent to 40 percent minority districts, and the representatives have been some of the most aggressive in arguing against civil rights legislation — doing things that are directly contrary to the interests of the minority community. Mike Parker, who’s from Mississippi, is one of the most conservative members of the Democratic Caucus. Between 36 percent and 40 percent of his district is black. Where in the hell is the influence?” (Parker switched to the Republican Party.)

Edward Blum, however, said that racial gerrymandering has aggravated racial polarization, and that if white representatives had more minority constituents, they would be more responsive to minority interests. He also said that his Campaign is not a threat to minorities. He pointed to his parents’ involvement in the civil rights movement and his own background as a University of Texas student activist in the 1960s, where he co-chaired a student group that pressured the administration to increase minority enrollment. He said he became disillusioned with liberal solutions to American political and economic problems.

Back to ’54

Blum, 44, looked back at his 20-year-old self, who fought for affirmative action, and said that while he now supports minority recruitment, he wouldn’t “suspend the rules” to encourage greater enrollment of minority students. In a letter to the Houston Chronicle, Blum derided African-American State Senator Rodney Ellis, a successful Houston lawyer and investment counselor, for defending affirmative action. Blum wrote that Ellis’ “privileged” daughter, Nicole, shouldn’t expect special preference over poorer but “better qualified” white students.

Asked about Blum’s version of affirmative action, Ellis was blunt. “I think his argument is ridiculous,” he said. “He’s either very naive or very insensitive. In either case, he’s a very dangerous man, because in racial matters, he wants to take us back to 1954. Either he doesn’t know American history, or he doesn’t care.”

Ellis said that a return to “color-blind” districting will result in an inevitable decrease in the number of minority representatives, although the effect might not be apparent immediately. “I’ve got a record and a war chest, so I could survive,” said Ellis. “But a new black candidate, without an established reputation or funding, could not succeed.”

Democratic Representative Eddie Bernice Johnson of Dallas echoed Ellis’ comments. Her 30th district will also be redrawn as a result of Blum’s lawsuit. “This [color-blind argument] is just a smokescreen,” Johnson said. “This is a part of the racist reaction to overturn affirmative action in general. Minorities were never elected until we had minority districts.”

Blum said the elections of minority politicians in white majority areas — notably Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk and a few others in local Texas elections — were evidence that “bloc voting” by race is no longer a crucial concern for redistricting.

But Chandler Davidson cites recent studies that indicate that a preponderance of evidence is on the other side. “The increase in the number of black legislators in 11 Southern states,” said Davidson, “is due almost entirely to the fact that under pressure from the Justice Department, the state legislatures between the early 1970s and the late 1980s simply increased the number of majority black districts in those legislatures. And I just think that’s very powerful evidence that people tend to overlook.”

Heir-ogance?

Perhaps Blum’s most controversial claim is his insistence that he and his Campaign are the true heirs of the civil rights movement, of the people who risked their lives and livelihoods to defend the rights of people of color to live free of racial segregation, to vote, and to take full part in public and political institutions. Blum passionately insisted that the historical civil rights groups like the NAACP and LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens), which he calls “professional racial advocacy groups,” have turned away from the vision of a color-blind America because it was just too difficult, while he and his group remain undaunted. “They have capitulated — I will not capitulate,” he said. “That color-blind ideal is worth fighting my entire life for, and I’m not going to say, after seven years, or 10 years, or 20 years, ‘Gee, it doesn’t seem to be working right; therefore, let’s come up with some new doctrine of civil rights.’ I reject that outright.”

Asked why, despite these proclaimed convictions, virtually no civil rights activists support him and his Campaign, Blum pointed to U.S. Representative John Lewis of Georgia, recently profiled in The New Republic. Lewis, wrote reporter Sean Wilentz, “worries that black majority electoral districts will ensnare blacks in separate enclaves, the exact opposite of what the civil rights movement intended.”

Lewis said Wilentz’s characterization was inaccurate. He said that the Campaign’s claim to a civil rights legacy is illegitimate. “I would like to see the day come when race would not be a factor,” Lewis said, “but that day is not here yet. So you’ve got to have majority-minority districts.” For Lewis, there is bitter irony in the claim of opponents to affirmative action that they are carrying on the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., even while they are attempting to undo the central legislative reforms brought about by the civil rights movement. “They love to [quote King] about people not being judged by the color of their skins but by the content of their character,” said Lewis. “That is the ideal, but we’re not there yet. We have not arrived at the ideal of an interracial democracy.”

In the absence of that ideal, said Lewis, it is hypocritical to attempt to defeat the legal weapons designed to move toward equality. Lewis minced no words about the most recent court decisions. “The Supreme Court,” he said, “is gutting the heart and soul of the Voting Rights Act.”

Since the courts are no longer acting as “sympathetic referees” in the struggle for civil rights, the only effective response will be at the ballot box, Lewis said. “If the Voting Rights Act or the Civil Rights Act were before this Congress, they would not pass. If anything, this Congress would repeal them. We need to mobilize people to maximize the use of the vote, to get people elected who are going to be sympathetic to the Voting Rights Act, and an administration that will have an opportunity to change the court.”

NAACP attorney Charles Drayden said that supporters of minority rights must look beyond the courtroom to fight their battles. “I’m not sure a legalistic strategy is the best thing. By removing those districts, you will also remove a whole group of ideas that will simply not show up on the floor of the House of Representatives or in the Senate,” he said.

“A color-blind America will result in an America in which everyone sounds the same, and everyone will have to articulate the same points of view in order to get elected.” said Drayden. “I have real concerns with whether the mission of the Campaign for a Color-Blind America is a noble one, or if it’s really an attempt to make sure that certain ideas simply aren’t expressed in the legislative arena.”

Tags

Michael King

Michael King is associate editor of The Texas Observer. Research assistants were Katy Adams and Carol Stall. Funding and additional research were provided by the Investigative Action Fund of the Institute for Southern Studies, the publisher of Southern Exposure. (1996)