This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 3, "Way Up North in Dixie." Find more from that issue here.

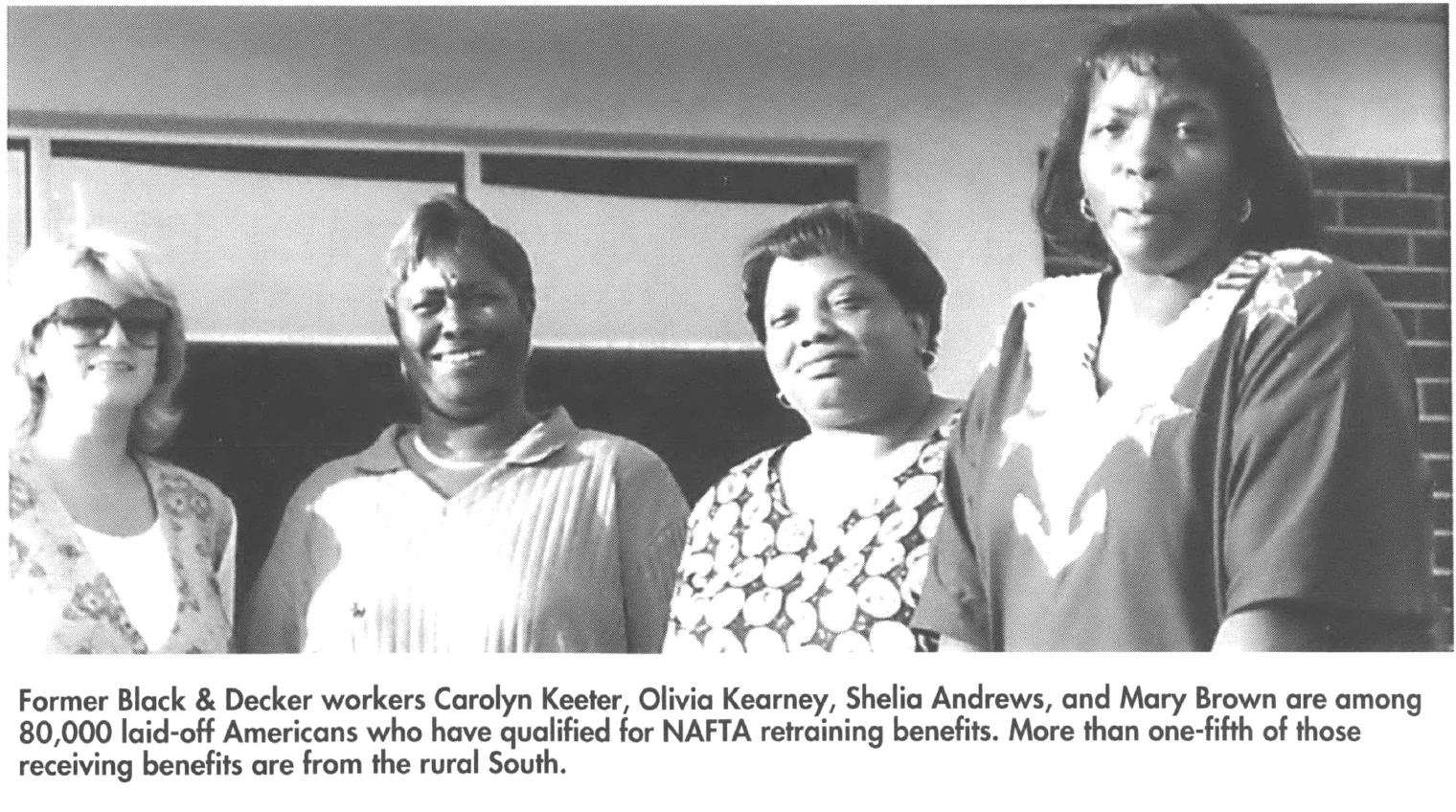

Olivia Kearney worked at the Black & Decker plant in Tarboro, a small town in eastern North Carolina, from the day it opened in 1971 to the day it closed last December. She and 800 other employees were laid off when the power-tool maker decided to shift production to Mexico after passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement, better known as NAFTA.

“It was sad, of course,” recalls Kearney, who spent half of her 48 years working for Black & Decker. “But I’m just not good at sitting around.”

Instead of feeling sorry for herself after the shutdown, Kearney contacted the U.S. Department of Labor and learned about job retraining and extended unemployment benefits available to workers laid off as a result of NAFTA. “I called up Washington myself, and it’s a good thing I did,” she says. Kearney and some coworkers organized a petition, and everyone at the Tarboro factory qualified for the federal retraining program. Kearney studied industrial maintenance and quickly landed a new job that pays as well as Black & Decker.

The story, it seems, has a happy ending. Black & Decker, by slashing labor costs, has better equipped itself to take on the challenges of a competitive global economy. Kearney, by taking advantage of federal job training, has repositioned herself more competitively in the global labor force. Even Tarboro, a community of 11,000, appears to be thriving. Well-preserved Victorian homes line the neatly groomed town common, and local merchants continue to sell their wares along the four-block stretch of Main Street as they have for half a century.

Yet beneath the quaint facade are signs of the deep scars left by the Black & Decker shutdown. Unemployment is up by a third. Tax revenues needed to pay for schools and social services are down. And a few storefronts along Main Street are boarded up, an ominous indication of things to come.

“Everyone understands this is a shared loss of the whole community,” says Town Manager Joe Durham.

As NAFTA enters its fourth year, that loss is increasingly being shared throughout the U.S. economy. Layoffs related to the trade pact are accelerating throughout rural America, especially in the South. Rural workers comprise only 21 percent of the U.S. workforce, yet they have suffered 46 percent of NAFTA-related job losses. Of the rural layoffs, 42 percent occurred in the South.

Why has the rural South been so hard hit? What kind of toll are plant closings taking on rural communities? The answers lie beyond the bounds of Washington and Wall Street, in towns like Tarboro. Like scientists charting the blast of an atomic bomb, economists tracing the impact of NAFTA must work from the epicenter of the explosion outward.

Ground Zero

Olivia Kearney actually started working for Black & Decker before the company opened its factory in Tarboro. To lure the well-known power-tool maker to Edgecombe County, officials built a training center for the firm to use as a production site for six months while the new factory was under construction. When the plant finally opened, it became the largest employer in town.

Workers say the company led them to believe their jobs were secure. In 1991, Black & Decker initiated a high-tech training program boldly named “Tarboro 2000.” Kearney signed up and spent seven months learning how to use robotics to produce electrical chargers for hand-held tools. “They made it seem like we were one big family,” she recalls. “We just had to jump on the bandwagon, and we’d all ride into the next century together.”

The ride proved shorter than Black & Decker had promised. While the company was promoting its plans for Tarboro, it was also lobbying heavily for NAFTA. Black & Decker promised it would not ship American jobs to Mexico if the trade agreement passed. A few weeks before Congress voted on the trade pact in 1993, company spokeswoman Barbara Lucas told a reporter, “We’re not going to move jobs in or out of the U.S.”

But that is exactly what Black & Decker did in Edgecombe County. The company insists it shipped jobs from its Tarboro factory to other towns in the United States. According to a report by the Department of Labor, however, the Tarboro 2000 program ended prematurely because Black & Decker shifted production to Mexico. The finding was supported by internal company memos obtained by workers and by reports from Tarboro employees who were sent to Mexicali, Mexico, to install equipment from the North Carolina plant.

The appeal of Mexico is clear. Hourly production wages at the Tarboro plant ranged from $8 to $16. By contrast, factory wages in Mexico average $1.37. In effect, NAFTA gave companies extra incentive for producing in Mexico by lowering investment and tariff barriers, thus making it more profitable to export goods to the U.S. market. In 1995 alone, American companies built 600 new factories in Mexico. Many other U.S. firms were hurt by increased imports from Mexico.

Kearney and her former Black & Decker co-workers are among nearly 80,000 laid-off Americans who have qualified for NAFTA retraining benefits (only a small fraction of the total NAFTA job loss, since many workers do not know about the program or do not meet its narrow qualifications). About 15,000 of those workers — nearly a fifth of those receiving benefits — are from the rural South.

Why has the region been so hard hit? The answer lies in the same reasons why many companies moved south in the first place — to take advantage of cheaper land and labor than they could find in urban areas, and to evade unions concentrated in Northern cities. For runaway shops like Black & Decker, the move to Mexico was just another step in the pursuit of ever cheaper labor.

Asked if anyone had ever tried to organize a union at the Tarboro plant, Kearney and three of her co-workers burst out laughing. Whenever talk of organizing came up, they say, plant managers threatened, “If you want to make us close, organize a union.”

Mary Brown, a 17-year veteran of Black & Decker, says the strategy of intimidation worked. “But the funny thing is that we might still have our jobs if we had unionized,” she says. “Someone in management told us the company really wanted to close their Canadian plants, but the unions there have a contract that demands three years of severance. It was cheaper to lay us off because we only got a week for every year we worked.”

Indeed, the Tarboro plant closing shows up as a big positive on the Black & Decker balance sheet. According to a company report, the shutdown helped reduce annual operating expenses by $60 million — in a year of record sales and profits.

Saving Jobs and Towns

Although NAFTA has given companies wide latitude to abandon workers and communities, there are a variety of efforts underway that could protect towns like Tarboro from the whims of globetrotting corporations like Black & Decker.

1. Attach Strings to Tax Breaks. To entice Black & Decker to Tarboro, the county gave the company a brand-new training center — no strings attached. Since training, tax breaks, and other subsidies are an investment by taxpayers, some communities are beginning to demand something in return. Santa Clara County in California now has a law that requires firms applying for tax breaks to create jobs that pay at least $10 an hour, with benefits, and to keep those jobs in the county. If the company reneges, it must repay the full value of the tax subsidy.

2. Require Companies to Negotiate. In certain European countries, companies planning a plant closing must sit down with workers and government officials to explore ways to avoid the shutdown. Olivia Kearney, the laid-off Black & Decker employee, says many of her co-workers would have offered to take a pay cut or make other changes to keep their jobs. Even if the company had rejected their offers, Kearney says, the workers would have appreciated the opportunity to make their case.

3. Promote Community Ownership. The Black & Decker plant in Tarboro remains empty, a tremendous waste of a facility that cost $3 million when it was built in 1971. In some communities, workers, citizens groups, or local governments have bought plants and kept them operating. By preventing the ripple effects of a shutdown, communities can benefit even if a plant just breaks even. Local ownership also ensures a higher level of concern for community interests.

Some states allow local governments to use the power of “eminent domain” to take over plants about to be closed, as long as the seizure serves a public purpose and the owners receive “just compensation.” Pressured by the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America, the city of New Bedford, Massachusetts, threatened to take over a plant owned by Gulf and Western. In response, the company agreed to sell the plant to another firm that kept the plant open for seven years.

4. Enforce Stronger Labor Rights. Unfortunately, no matter how hard communities work to retain jobs, corporations will continue to move overseas as long as a massive wage gap exists between the United States and underdeveloped countries. Mexican workers who try to organize and press for higher wages commonly face being fired and blacklisted.

To prevent such unfair labor practices and level the playing field between American and Mexican workers, labor unions and others demanded that NAFTA include provisions to punish violators with trade sanctions. But the labor agreement attached to NAFTA is weak, and the process for filing complaints is prohibitively bureaucratic. Only four were filed during NAFTA’s first two years, and none has resulted in improvements for workers. However, citizens groups remain committed to fighting for stronger enforcement mechanisms to protect labor rights in future trade agreements.

Consumers play an important role in defending worker rights. Last fall, citizens held demonstrations outside Gap clothing stores to protest labor violations at plants run by company contractors in El Salvador and Honduras. In response, Gap agreed to allow independent monitoring of its overseas plants.

Local governments can also wield power over corporations. The most successful example is the sanctions movement against apartheid, which mobilized hundreds of municipalities to stop supporting firms that did business in South Africa. Governments could use the same approach to punish labor rights violators, halting investments and contracts with companies shipping jobs overseas.

— Sarah Anderson

“A Part of Themselves”

But creating a balance sheet that accounts for the true cost of NAFTA requires going beyond the bottom line of companies like Black & Decker. A full reckoning would start with the expense of unemployment insurance and retraining for laid-off workers. Over the long term, it would also include the costs of families forced to relocate to find work, and the drop in income levels for those unable to find jobs that pay as well as Black & Decker.

The Black & Decker closing was the largest of three major layoffs in Edgecombe County last year that drove the unemployment rate to 10.7 percent, almost double the national average. As in many small towns, job opportunities in and around Tarboro are scarce. Studies show that rural residents have a harder time finding new jobs at comparable pay than their urban counterparts.

The Tarboro workforce at Black & Decker was three-quarters African American and two-thirds female. Both groups have been especially hard hit by NAFTA, primarily because they are employed in large numbers in the apparel and electronics industries, which have suffered the most NAFTA-related layoffs. In addition, a study by the Joint Center on Political and Economic Studies indicates that dislocated African Americans are more likely than whites to take substantial pay cuts in their new jobs. The gap between the races is particularly wide in rural areas, where the poverty rate among African Americans is 40 percent, almost three times that of rural whites and a third higher than the rate among urban African Americans.

Rural communities like Tarboro are often held together by support networks of extended families. But the Black & Decker layoff has strained this safety net by hitting entire families in one blow. Olivia Kearney, for example, has a son, two sisters-in-law, a niece, and a nephew who also worked for Black & Decker.

The plant closing also exacted a devastating psychological toll on workers. Average seniority at Black & Decker was 10 years. Fifty employees had worked at the factory for 25 years.

For older workers, the layoff “was almost like experiencing a death in the family,” says Cyndi Phelps, a counselor with the local Employment Security Commission. “It was like losing a part of themselves.”

Phelps urged workers to enroll in job training immediately so their unemployment benefits would last until they completed the program. But many of the workers were simply too traumatized to move on so quickly. Six months after the layoff, only 180 of the 800 Black & Decker workers had signed up for training. An even smaller number had found employment.

Many workers worry that they will be forced to leave the town in which they have spent their entire lives. Although Labor Secretary Robert Reich describes mobility as the key to success in today’s economy, the pressure to relocate is devastating for many rural residents.

“Before I starve, I will move,” says Mary Brown. “But until I get to that point, I’m not leaving. My roots are here. I just love old Tarboro.”

Temps and Mammograms

The ripple effect of the plant closing has extended outward from workers like Mary Brown to the rest of the community. The next to feel the effects were merchants and suppliers who did business with Black & Decker. Although Brown was the only person in her family employed directly by the company, her father runs a taxi and delivery service that depended on the company for at least 10 percent of its business. His is one of a large number of firms forced to scramble to make up for the Black & Decker closing.

One of the hardest hit was Megaforce, an employment agency that supplied Black & Decker with low-paid temporary workers. Helping Black & Decker develop a more “flexible” workforce of contract employees had been Megaforce’s bread and butter for the past decade. Last year, the agency supplied Black & Decker with about 600 workers, many of whom had been “temps” with the company for as long as six years.

Another firm hurt by the plant closing was Service America, which ran the employee cafeteria at Black & Decker and catered special corporate events. All over town are banks, rug cleaners, a warehouse, mechanics, office supply stores, and a host of other small businesses that relied on the tool maker for much of their income.

On Main Street, shopkeepers are tight-lipped about their potential losses. Jeanette Jones, who owns a TV and appliance store with her husband, admits that they “might have felt the pinch a bit,” but hopes that there won’t be any more negative publicity about the layoffs.

“We’ve had so much bad news that people are scared even if it’s not their own plant,” Jones says. “They’re nervous about making purchases.”

Community organizations that will lose donations from Black & Decker are too numerous to list. The company sponsored car races, softball and basketball teams, the March of Dimes, Special Olympics, and a Christmas drive for needy families. When Olivia Kearney’s son was raising money for the high school band, Black & Decker bought $200 worth of oranges from him and gave them to the poor. Likewise, when the local volunteer group Women With a Vision needed door prizes, its members knew where to turn.

The local hospital is also suffering from the layoffs. Under the Black & Decker health plan, workers who got sick had to go to Heritage Hospital. Now, many are unable to afford health care. The company offered a Women’s Wellness program that provided free Pap smears and mammograms. Without coverage, many women in Tarboro must forego such preventive care to meet basic family expenses.

The health of the town itself is also threatened. According to Town Manager Joe Durham, Tarboro will lose about $250,000 in annual property tax revenues as a result of the plant closing —1.5 percent of what the town collects. Figuring in lost revenues from payroll taxes and sales receipts, plus increased expenses for various social services, one county commissioner predicted that the Black & Decker layoffs could drive up the local tax rate by as much as 12 percent in 1997.

Memory Book

It is clearly impossible to measure all the costs associated with a layoff like the one that hit Tarboro. Yet even a cursory look at one town raises serious questions about whether NAFTA is living up to its promise to increase U.S. competitiveness. The key question, it would seem, is “competitive for whom?”

Last spring, IBP Corporation picked Tarboro as a competitive site for one of its hog slaughterhouses. Known for its high injury and illness rates and relatively low pay, the meat-packing giant tends to locate in economically depressed areas. Although the county eventually rejected the project because of the high cost of treating hog waste from the processing plant, a majority of commissioners were otherwise supportive of the bid, pointing out the desperate need for jobs and tax revenues.

Tarboro leaders are realistic about an economy in which most new jobs are less than desirable. While few are as grueling as slaughterhouse work, most new jobs are part-time, temporary, or low-paying positions in the service sector. Thus, the pro-NAFTA promise that retraining will improve the lives of workers rings hollow. Even dislocated workers who do find satisfactory new employment are unlikely to come through the experience unscathed.

Six months after her last day on the job, Kearney’s bedroom is still decorated with a half-dozen framed certificates of achievement from Black & Decker. Her son, Philuster Jr., laid off by Black & Decker after 11 years, remains unemployed and lives at home. Her husband, Philuster Sr., has worked nearly 30 years at a local textile plant, but Kearney knows that textile companies are leaving the United States in droves to take advantage of lower wages overseas.

On a night out at the Red Lobster in Rocky Mount, 30 miles from Tarboro, Kearney reminisces with former co-workers Mary Brown and Shelia Andrews about their combined 54 years at Black & Decker. Kearney, in a fuchsia pantsuit and gold jewelry, and Brown and Andrews, also well-dressed with fresh manicures, hardly look the part of down-on-their-luck blue-collar workers. The women even manage to laugh about the day Black & Decker announced the layoff.

“They had security guards posted at all the entrances because they thought there was going to be a riot,” says Kearney, her eyes twinkling with amusement. “Then this man from corporate headquarters got up there. He was like a stranger in the night — we’d never seen him before.”

“He had a bullet-proof vest on!” adds Brown. “I really think he did! They were just so sure it was going to be a mess.”

Andrews nods. “The funny thing was that after the man read the piece of paper about the shutdown, everybody just went back to work. It was so quiet. I mean, I was thinking that somebody would have lost it, but they didn’t.”

When the women describe the company’s lavish farewell banquet, however, their tone turns bitter. The company invited employees and their families, gave away prizes, and videotaped the event as a memento. Kearney and other workers received a memory book dedicated to employees for “consistently making the Black & Decker Tarboro plant the #l plant.”

“That’s what they were really good at — making you believe it was a family-oriented company,” Kearney says. “But I guess we know better now. You don’t kick your family out into the street.”

Tags

Sarah Anderson

Sarah Anderson is a fellow and Karen Harris is a research assistant at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. Anderson co-edited a 50-page report entitled NAFTA’s First Two Years: The Myths and the Realities, published by IPS in March. (1996)

Karen Harris

Sarah Anderson is a fellow and Karen Harris is a research assistant at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. (1996)