This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

Southern clay couldn’t grow a lot of crops, but it grew generations of potters. From Native Americans centuries past who made vessels for food storage and ritual to Southerners who today create forms that sell for hundreds of dollars as pieces of art, pottery is a strong South tradition.

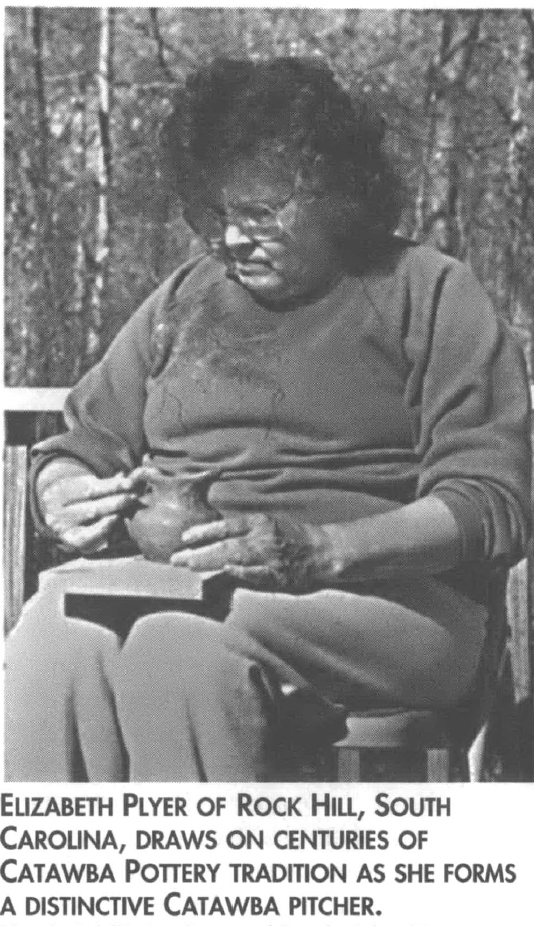

Catawba Indians in South Carolina have used pottery for ceremony, storage, and to make a living for the past 4,500 years. “We’ve been around since long before Columbus. Pottery used to put food on the table when Europeans first came and bought the pieces,” says Wenonah Haire, Executive Director of the Catawba Cultural Preservation Project in Rock Hill, South Carolina. “Catawba pottery has never ceased being made traditionally.”

Master Catawba potters still dig their clay from the ground, build their pieces by hand using the coil method, smooth the pieces with Catawba River smoothing stones passed down from potter to potter, and burn the pots in pits or fireplaces. The result is a pot or animal figure with the look of polished wood.

Although Catawba master potters won’t share many of their secrets with outsiders, the Cultural Preservation Project wants to make sure the tradition doesn’t die out as their language did. The Project has started classes, only open to Catawbas, to teach pottery. Haire says the program attracts some young people, but also older women who learned the skills as girls but couldn’t continue because they had to go work in the mills to make money. Now they have more time to re-learn the traditional pottery methods. “It’s in the blood,” says Haire.

Pottery making also thrived along the Texas border where Mexicans brought their skills north. Although Africans imported pottery traditions, including face vessels and jugs with double spouts, few slaves were allowed to practice the craft formally. Thus, there are relatively few African-American potters today. European groups like the Moravians started making pottery in the 1750s in North Carolina, where their traditions are still strong.

“Southern pottery is still very traditional in the way it’s made,” says Charles Zug III, professor of folklore at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and author of Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina. “Families still have control of the business. Pottery hasn’t become industrialized as in the North, and the region is blessed with an abundance of clay.” As potters in the North were replaced with assembly lines and factory-produced wares, Southern pottery in the clay-rich Piedmont areas remained a family affair. Potters passed on traditional salt glazes, wood-fired kiln techniques, and vessel shapes through the generations.

“The shapes and forms of Southern pottery — like whiskey jugs, pie plates, and pickling crocks — are very distinctive,” says Ben Owen, whose family has been creating pottery since the mid 1700s in Seagrove, North Carolina. His grandfather was the first to take up the craft full-time as a means of making a living, and he was the principal potter in the area known as Jugtown for 36 years. At age nine or 10, Owen took up pottery and kept the family tradition alive. He says that in earlier times, pieces were used for food storage and bartering. Now pottery is art for collectors. “Customers come in and buy my teapots just to look at,” he says, “but I encourage them to make use of them — all my pieces are functional, too.”

The area around Owen’s hometown of Seagrove in Piedmont North Carolina has become a kind of pottery mecca in the South, hosting dozens of potters and attracting craftsfolk and collectors from all over the world. Recently, a citizen group including Zug, potters, and community residents worked to create the North Carolina Pottery Center. Through a combination of public and private funding, the group has raised money to draw up plans and buy land. The center is slated to open in a couple of years.

The group has been pleased with the support it’s gotten: “We’re excited to have the opportunity to open a museum and education center to teach about and display this rich tradition,” says Zug.

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)