This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

When she was a little girl, Deborah Compton-Holt used to attend civil rights marches and meetings with her father in her home town of Greensboro, North Carolina. Most of those adventures have faded into hazy memory — except one. “I remember when Martin Luther King came to Greensboro because everybody was so in awe with him,” she says. “This man could speak and captivate even children.” That day, her father, an engineer for Burlington Industries, joined King at a downtown sit-in to protest legalized segregation, and the two men went to jail together.

The Comptons didn’t know King personally, but they, like many of their neighbors, considered him part of their family. “He was closer to you than some of your relatives,” she says. “The day he passed, our whole neighborhood — you could hear a pin drop. Everybody was stunned.”

As King’s birthday approached this year, almost three decades after his assassination, Compton-Holt found herself thinking about her father’s brief connection to the civil rights leader. She knew her co-workers at the Kmart distribution center in Greensboro planned to commemorate the holiday with a large civil disobedience. Kmart pays the mostly minority workers at the facility sharply lower wages — almost $5 an hour less — than it does at a dozen other distribution centers with whiter work forces. To protest the disparity, the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees (UNITE) was staging a non-violent demonstration at a local Kmart store.

Compton-Holt, a devout Baptist with vibrant eyes and a broad, motherly smile, had participated in some legal protests before. But she had to give extra thought to breaking the law. “I used to make hasty decisions in my younger days,” she says. “Now I’m into spiritual decisions. I try to let God make the decision for me.”

So she prayed. She fasted. She raised the issue at a family dinner. “My mom and I did a lot of talking about the civil rights movement, and that brought up a lot of memories of my dad,” she says. She thought about how poverty has plagued so many African Americans, tearing even working families apart. “I thought if we had not stopped fighting and struggling, we wouldn’t be in the shape we’re in now. It just put everything in perspective for me.”

On King’s birthday, the 44-year-old merchandise packer slipped a “Don’t Shop at Kmart” T-shirt over her sweater, caravaned with co-workers to the Kmart store, and marched with about 200 others into the parking lot — until they were standing face-to-face with a platoon of police in riot gear. The store’s manager came out and told the protesters to get off the property. A police officer warned, “Those who do not leave will be arrested.” As planned, most of the group retreated. But Compton-Holt stood there, thinking of her father.

“It just brought back all those memories,” she says. “There were a lot of tears, but they weren’t tears of sadness. It was tears of ‘We’re doing this again.’”

She didn’t move. “There was no turning around. We just joined hands and prayed.” As they worshipped, police arrested 39 protesters and led them into a van, where they sang “Victory Is Mine” and “We Shall Overcome” all the way to jail. Except for the birth of her son, Compton-Holt says, it was the proudest event of her life.

There’s a lot of pride in Greensboro these days. It energizes the UNITE union hall, an industrial brick building one block off a major freeway. It draws people to the Faith Community Church, with a congregation that ministers to the poor in a gritty downtown neighborhood. It permeates the suburban Quaker campus of Guilford College. It electrifies the Kmart parking-lot protests that have become more common than blue-light specials.

Working together, Compton-Holt and other blue-collar workers have joined forces with students, ministers, church members, and social-change activists to forge a workplace campaign that draws on the historic connections between the labor and civil rights movements. They’ve turned a run-of-the-mill union protest into a community-wide struggle — a battle not just for higher wages and better working conditions, but for a new set of values that place human dignity above corporate growth.

The Kmart protest offers “the possibility of our leading the nation to a whole new sense of how we define community,” says the Reverend William Wright, pastor of Greensboro’s New Zion Missionary Baptist Church. “Is community defined by its citizens, or is community defined by corporations that come in and set up little Mexicos in our cities?”

Just as Greensboro activists sparked the civil rights movement with a sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in 1960, the new model for union activism emerging at Kmart could soon spread well beyond North Carolina. The AFL-CIO has launched its “Union Summer” — a $1 million campaign that deploys student activists to organize non-union plants in Atlanta, Charleston, Miami, New Orleans and 14 other cities. Greensboro demonstrates how a union can draw on its strength as an integral part of a community rather than allow itself to be isolated as an “outside force.”

“There’s a growing awareness within unions,” says Ben Hensler, a field representative for UNITE, “that if we’re going to be able to take on — and win — fights with companies like Kmart, we’ve got to be allied with the communities that are affected by the policies of these corporations.”

Incentives for Abuse

When Kmart announced its plans to build a hard-goods distribution center in Greensboro in 1992, expectations ran high among both local officials and workers. As the sponsor of the Greater Greensboro Open (GGO) golf tournament, the corporation had a stellar reputation in town — and the prospect of 500 new blue-collar jobs looked good. The city, county, and state offered $1 million of incentives, including sewer lines and road improvements. Job applicants lined up at the doors of the sprawling flat-roofed center, a building 35 football fields long, separated by barbed-wire fence from a predominantly black East Side neighborhood.

“I knew Kmart was a big corporation, and I knew they sponsored the GGO, and I’d shopped in their stores,” recalls Dave Blum, a 53-year-old merchandise packer. “I figured they’d probably be a good company to work for. I figured there’d be a future there.”

But as soon as the facility opened, Blum and his co-workers realized that any future there would be grim. On the shop floor, where workers package merchandise for shipment to Kmart stores in five Southern states, temperatures ran as high as 100 degrees. Bathrooms didn’t work. Breaks were rare, and workers were fired for the smallest infractions.

But worst of all were the attitudes of supervisors, many of them white managers imported from other Kmart facilities. According to employees, the standard management style consisted of ridiculing and shouting at workers. Female employees say managers routinely spied on them, followed them to the restroom, and made lewd comments.

“I’ve seen women cry taking abuse — but people needed the work,” says 48-year-old Governor Spencer, a lanky former postal worker hired by Kmart shortly after the center opened. When Spencer talked with the managers about the working environment, he says they replied, “You see these applications on the table? You don’t like it? Someone will take your place.”

Kmart flatly denies there were any problems with working conditions or harassment, but refuses to discuss specifics. But discontent was so widespread — and reports of sexual and racial harassment so legion — that workers began looking for a union to represent them. They settled on UNITE, which represented some of their relatives in the nearby Cone Mills textile plant.

Kmart fought the organizing drive, but its anti-labor efforts were a spectacular failure. By a two-to-one margin, the workers welcomed the union. Even organizers were stunned. “It was amazing,” says Ben Hensler of UNITE. “You never see a margin like that when the place is that new.”

Only after the union did some research, however, did the workers learn how bad their situation really was. UNITE discovered that Kmart paid its Greensboro workers dramatically less than their counterparts at every other distribution center in the country. The top hourly wage in Greensboro was $8.50, compared to a national average of $13.10 at a dozen other Kmart centers from Morrisville, Pennsylvania, to Ontario, California. In Newnan, Georgia, where the cost of living is below Greensboro’s, Kmart pays up to $14.

Kmart offers a simple reason: Low wages are the norm in Greensboro. “When the company opened the distribution center, it surveyed wage rates. They determined what the wages will be based on that,” says Kmart spokeswoman Mary Lorencz. “You can talk to people in the market who say they can live on that wage.”

But workers and their allies have a different explanation. At all but one of the other Kmart distribution centers, the majority of the hourly workforce is white. At Greensboro, minority employees make up two-thirds of the workforce. The wage disparity, say workers, comes from out-and-out discrimination.

After the union victory, UNITE and Kmart sat down to negotiate a contract. Lorencz says Kmart has been “negotiating in good faith.” The union accused the company of stalling. When it became clear that bargaining was going nowhere, workers decided it was time to go public.

In the Rough

The opening shot was the boldest. In April of 1994, the workers decided to crash the Kmart Greater Greensboro Open, a nationally televised tournament. “We had been telling Kmart, ‘If you don’t treat us right, we’re gonna pay you a visit at the GGO,’” says UNITE organizer Anthony Romano, a young Harvard-educated Southerner who came to Greensboro to organize Kmart workers. “And we’re a union that always follows through.”

So the workers dressed in polo shirts and blended in with the rest of the fans at the Forest Oaks Country Club — until 2 o’clock sharp. Suddenly, 60 workers stormed the 10th fairway, sat in concentric circles, locked arms, and started chanting. Police handcuffed the protesters and hauled them away, to the cheers of tournament spectators. “Club them like baby seals!” shouted one man.

The protest garnered plenty of media attention, but no progress in contract negotiations. After the standoff had dragged on for two years, workers appealed to their ministers at church — and Greensboro’s clergy listened. “These are our members,” explains the Reverend Wright, who heads a black ministerial alliance called the Pulpit Forum.

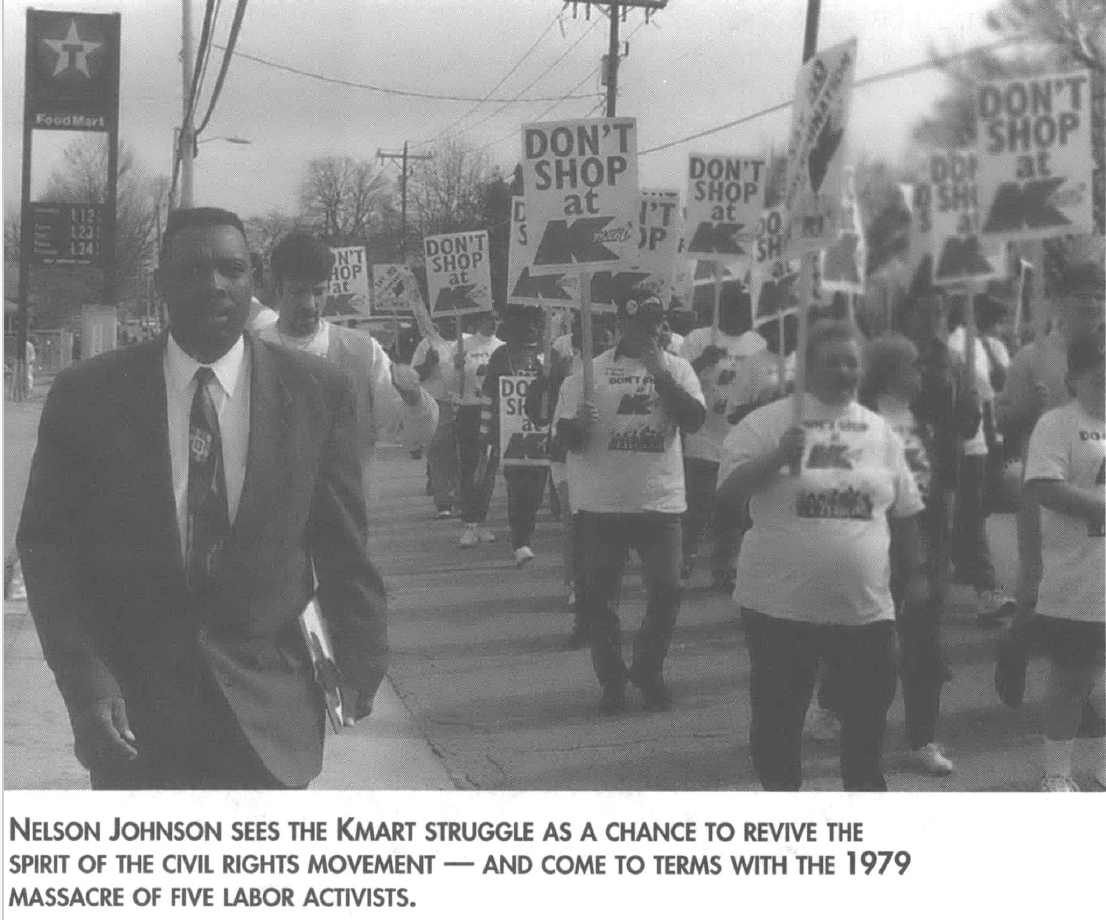

The ministers made two important contributions to the fight. First, they encouraged workers to think of their demand for pay equity as a campaign for civil rights. “All of it is connected by a struggle for justice,” says the Reverend Nelson Johnson, a community activist since his student days at North Carolina A&T University. “The struggle for racial justice and the struggle for economic justice are so closely intertwined. Was the struggle against slavery an economic struggle or a race struggle? Obviously both.”

Linking the labor and civil rights struggles is a time-honored idea. When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, he was visiting Memphis to support striking black sanitation workers. But these days, few activists make the connection. “There’s a big hesitancy on the part of unions to present things in that language, because they’re afraid of a backlash from their white members,” says Kim Moody, director of the monthly publication Labor Notes.

But many white workers at Kmart understood that any discrimination against the predominantly minority workforce hurts whites, too. “What affects one affects the other,” says Dave Blum. “My black union brothers make the same thing I do. We’re both held down.”

The ministers also revived the tactic of civil disobedience from the civil rights era. “People were ground down by these large corporate entities,” says Johnson, a soft-spoken man with striking blue coronas ringing his brown eyes. “We wanted to claim this fully as a legitimate struggle of this community. And if it required presenting our bodies as a living sacrifice, that’s a small price to pay to engage in turning this trend around.”

So last December, eight ministers held the first in a series of illegal protests, occupying a Kmart parking lot until they were arrested and jailed.

Their civil disobedience sparked a blaze of community support. White pastors, progressive activists, students, and elderly church members all vowed to lay their bodies on the line. Thirty-nine people were arrested at a January civil disobedience; in February, the number was 50. Ten thousand people signed a petition protesting working conditions at Kmart’s distribution center. The local NAACP turned down a $10,000 check from Kmart, earmarked for crime prevention and tutoring, saying the money could taint the organization’s support for the workers.

The widening demonstrations attracted many Greensboro residents, old and young alike, who had never participated in political protest. For Brittany Boden, a Guilford College senior, the Kmart struggle marked a “transformation from feeling silly as a student. There’s so much nourishment from this experience.” Mary Crawford, a retired textile worker, joined the protests after stumbling across a jailhouse essay by Martin Luther King Jr. “I began to cry,” she says, “and I knew I had to go. I know what it means to do good work and not get paid for it.”

Prayer and Planning

In a spartan room at Faith Community Church, 40 people sit in two concentric circles of folding chairs. A portrait of Frederick Douglass, the abolitionist leader, presides over a roomful of blacks and whites, students and septuagenarians, workers and community members, praying together.

“We thank you for the privilege of being a part of this struggle,” says the Reverend Greg Fleaden, pastor at Shiloh Baptist Church. A periodic call of “yes!” comes from the circle. “Thank you for the Kmart workers that take a stand at great risk. Give them the strength that they need. In Jesus’ name we pray.”

Then, as prayer gives way to planning, everyone turns to Deborah Compton-Holt. She’s wearing a brown suede jacket over her “Don’t Shop at Kmart” T-shirt, along with a red and black UNITE baseball cap. “Things are still kind of stagnant in the plant,” she says. “The company has put on a lot more pressure. Some people have quit.” She reports a “small victory”: a 50-cent-an-hour pay raise. But she and co-worker Calvin Miller make it clear that a half-dollar isn’t enough. “We’re going to have to escalate our pressure and take it beyond the boundaries of North Carolina,” Miller says. There’s talk of future protests and court appearances. But Nelson Johnson, standing in the back of the room, wants to make sure that the group doesn’t get bogged down in logistics. “We really need to talk about the tremendous victories we’ve won already,” he says. “I think what’s happening in Greensboro is awesome. The first piece of evidence is in this room tonight.”

Then his voice grows more preacherly. “The workers at Kmart distribution center are no longer separated from the community. We are all coming together, young and old, black and white. I think that’s a victory.” The room breaks into applause. “Check this victory out: The NAACP sent back 10,000 big ones!” By now the church is rocking, the clapping growing excited. “When poor folks and broke folks send money back — that’s a victory.”

From inside the circle come the words, “Praise Him!”

Finally, the pastor describes a meeting he had with the Greensboro Chamber of Commerce, in which the business leaders agreed to a set of principles to guide the city’s economic growth. They included decent wages, freedom from discrimination, programs to retrain workers, and sustainable development. “The head of AT&T and Lorillard came down and sat down and we’ve been in conversation ever since,” Johnson says. “That to me is revolutionary.”

The meeting slides back into logistics for a while. But before it ends in a prayer circle, Johnson gives voice to the feeling that permeates the night: sheer gratitude for being in this room with dozens of other people struggling for a just community.

“We’re in no ways tired yet,” he says. “To have walked away from our brothers and sisters at Kmart would have denied us this moment.”

Pacifism and Violence

For Nelson Johnson, such a moment has been long in coming. The 53-year-old pastor has survived two defining episodes in Greensboro’s history — episodes that set the stage for the Kmart battle.

The first was the civil rights movement, which placed Greensboro in the national spotlight. In February 1960, four black freshmen at North Carolina A&T University staged a sit-in at the lunch counter of the downtown Woolworth’s. By the end of the year, 96,000 students around the country performed similar acts of resistance. Johnson continued the tradition a few years later as an A&T student leader; in 1966 he was arrested for refusing to leave a whites-only restaurant called the Apple Cellar.

Johnson says Greensboro’s civil rights history continues to provide inspiration — not only to him, but to many in the Kmart struggle. “Woolworth’s represented the community standing up against injustice,” he says. “The churches and citizens here and the workers at Kmart are affected by this history and tradition, and it has meaning when you call it up again. It’s certainly something that you can get strength from.”

The second defining event was the 1979 assassination of five anti-racist demonstrators by members of the Ku Klux Klan and the Nazi Party. The victims were members of the Communist Workers Party (CWP), an organization of young activists who had tried to take over three inactive textile union locals.

On the morning of November 3, as the CWP assembled for an anti-Klan march at the Morningside Homes public housing project, nine carloads of white supremacists wheeled into the area. The crowd began chanting, “Death to the Klan!” The Klansmen and Nazis got out of their cars. A fight broke out. The supremacists grabbed their rifles, pistols, and shotguns. Eighty-eight seconds later, five demonstrators lay dead or mortally wounded.

Although the murders were captured by television cameras, an all-white jury acquitted the Klansmen and Nazis. A federal trial ended in one guilty plea and several acquittals.

Only one member of the CWP’s top leadership survived the shooting: Nelson Johnson. During the melee, a white supremacist rushed him with a knife and stabbed him in both forearms. Police arrested Johnson and charged him with inciting a riot.

The Klan-Nazi shootings cast an immediate and lasting chill over labor organizing in Greensboro. The massacre deeply divided progressives, some of whom didn’t want to be seen as supporting communists or the unions they tried to revive. Workplace organizing fell almost to zero — and businesses took advantage of the lull.

“The shootings had such a chilling effect on labor relations in Greensboro,” says Joe Groves, who coordinates the Peace and Conflict Studies Program at Guilford College, “that for years we have been getting companies like Kmart who feel like they can safely come in and offer low wages, because labor was thoroughly intimidated in 1979. And they were right.”

The Kmart protest brought activists back together — and forced them to confront what had happened that autumn day. “Kmart was an opportunity,” Johnson says, “for the hurt and pain of ’79 to get expressed.”

Beyond Greensboro

In a cavernous cinder-block meeting room, a gospel choir rouses hundreds of men and women to their feet. They wave their arms, clap their hands, and sing along to an updated version of “Down by the Riverside.” People pour into the room, fresh off buses and vans from Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Red, white and blue helium balloons hover above folding chairs.

On this spring day, Kmart workers have taken their struggle on the road, staging simultaneous protests in seven cities to kick off a national boycott of the retail chain. At the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers union hall in downtown Atlanta, the crowd cheers feverishly for justice in Greensboro. They’re getting psyched up for the day’s big event: Georgia’s largest civil disobedience since the 1960s.

The Reverend James Orange, one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s closest lieutenants, gives the invocation. “Go with us,” he prays, “as you went with Daniel. Go with us as you went with Jeremiah. And bring us back safe and sound.”

But it’s William Wright who really stokes the crowd. He starts softly, but his voice grows more forceful with each sentence. “You can’t kill what God wants alive,” the Greensboro minister says. “If I go back to jail, it’s all right. I believe it’s a good day to go back to jail today.”

Two hours later, at a shopping center in the upscale Buckhead neighborhood, 1,000 protesters converge around a pickup truck parked in front of a Kmart store. A phalanx of police officers blocks the entrance. Two Kmart managers in blue suits stand with them, one wearing dark glasses and the other holding a General Electric video camera. A thicket of “Don’t Shop at Kmart” signs rises about the heads of the protesters. The crowd chants.

The moment of the civil disobedience approaches. Nelson Johnson climbs onto the truck bed and encourages listeners to revive the spirit of the civil rights movement. “We have been walking around for 35 years, and we are shaking off the dust that has accumulated on us,” he tells the crowd. “God bless you, and let us move forward. Victory is ours!”

And then, with the choir again singing a piercing rendition of “Victory Is Mine,” Johnson and Wright and 39 others march right past the line of police officers, through Kmart’s double doors. One thousand voices chant, “Shut them down! Shut them down!” The ministers sit silently between the inner and outer doors, praying, until the police arrest them and take them away.

The last word of the afternoon comes from Deborah Compton-Holt. She too stands on the truck bed, microphone in hand, sounding much like the civil rights activists her father used to take her to hear when she was a child.

“Praise God, everybody. Praise God,” she tells the crowd. “As long as God stands on my side, we will win this war.”

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)