Nickels and Dimes: The Child Support Crisis

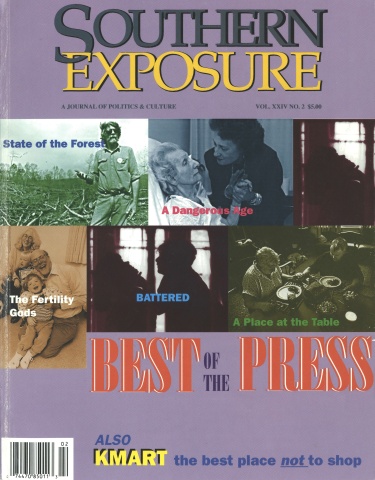

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

This five-part series appeared at a time when many people newly elected or re-elected to office in North Carolina and elsewhere were talking about taking steps to get people off welfare. With his stories of the fractured child support collection system in Buncombe County, North Carolina, Mark Barrett helped direct some of the lawmakers’ energy in a different direction. The articles showed that, in many cases, child support could go to people who are now receiving government assistance to get by.

Coincidentally or not, a few days after legislators received reprints of the series and an accompanying editorial, state lawmakers pushed through legislation that had been languishing in the North Carolina General Assembly. The new laws provide much-needed assistance in the state’s child support collection efforts.

ASHEVILLE, N.C. — According to her mother, 11-year-old Allison Elizabeth Hines got her name from her father.

And that’s about it.

Since Elizabeth was born in April 1984, taxpayers have spent little more than $10,000 to help her mother, Almeanor “Mimi” Hines, feed and clothe her.

The man Mimi Hines says is Elizabeth’s father, Tommie Lee Allison Jr., apparently hasn’t paid a dime.

North Carolina’s child support enforcement system has tried twice to make Allison contribute to the cost of raising Elizabeth and failed both times.

Unfortunately for millions of children and millions of taxpayers across the country, that’s nothing unusual.

When the U.S. Census Bureau studied the 10 million women who lived with a child under 21 but not with the child’s father in 1989, it found that only 2.5 million were receiving child support from the child’s father and receiving everything they were due.

Another 1.2 million got part of what they were due, and the remaining 6.3 million got the same thing that Mimi Hines has gotten to raise Elizabeth.

Nothing.

Talk all you want about welfare and the American family — and the folks in Washington and Raleigh have been talking plenty lately — but at least in terms of the raw numbers of people affected, welfare is small potatoes when compared to child support.

“The failure of absent parents, mainly fathers, to pay child support is a national scandal, one thing that has huge consequences for taxpayers, governments, mothers, and most important, children,” U.S. Senator Joseph Lieberman (D-Conn) wrote recently.

As divorce and single parenthood have risen over the past 20 years, child support enforcement programs have the potential to directly affect almost 18 percent of the population as either an absent parent, custodial parent, or child — nearly 40 million people in 1990.

And that figure is rising quickly. Experts on the family now estimate that half of all children born in 1994 and beyond will live in a single parent home — or some other arrangement — at some point by the time they turn 18.

The nationwide child-support enforcement system now seeks to collect on behalf of parents on welfare or any parent who pays a small fee. But when Congress authorized the creation of the system in 1975, the sole idea was to make absent parents pay the costs of raising their children so taxpayers wouldn’t have to pay through welfare.

An 11.9 percent rate of success probably wasn’t what lawmakers had in mind.

Of the $20.2 billion in Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) the nation spent on families eligible for child support in the federal fiscal year ending in September 1993, the child support enforcement system was only able to recover $2.4 billion from the children’s absent parents.

A Buck a Day Mimi

Hines isn’t looking for billions — tens and twenties would help a lot, thank you.

But first, someone has to find her children’s fathers.

Hines has raised three children at her modest home in West Asheville. Of their three different fathers, only one has made any child support payments, Hines says.

Uncle Sam has been a lot more helpful. Hines said she went on welfare shortly after having her oldest son, Dran, now 18. She received AFDC payments until she started making enough money as a housekeeper to get off the program last May, she says.

Taking public money isn’t something she is proud of, she says, but it seemed like the best way to raise her children.

“It was embarrassing to me to tell (the kids), ‘We’re on welfare, and we can’t do no better,’” she said. “I blame myself. I should have handled myself a bit different.”

But, Hines said, welfare allowed her to stay at home to take care of her kids.

“I wanted to be here for them,” she said. That decision has paid off, she says. Unlike some of their peers, Hines’ children have stayed in school and stayed out of trouble, she said.

Just the same, life would have been a lot easier had she gotten more money from her children’s fathers, she said.

Dran’s father, James Burgin, 51, of Asheville, is apparently the only one of the three who has remained in the area. He is also the only one who has made child support payments.

And those payments, court records show, have come only sporadically, after Burgin was repeatedly hauled into court under threat of jail.

Dran was 7, according to records, before his father made more than $500 in payments in any one year.

Child support workers “said they didn’t know his whereabouts, and he was right up the street,” Hines said. “We would see him just about every day.”

From 1987 through 1992, Burgin made a total of $2,282 in child support payments. That’s $380 a year, or $31.70 a month. Much of the money represented tax refunds or unemployment payments that the government intercepted before they reached Burgin.

And Burgin, who has been making regular payments for the last year-and-a half, is the success story.

There is no record that Hines ever received anything from the father of her second child, Margaret, 16.

That leaves Tommie Allison.

Nobody Home

People like Allison don’t even show up in many of the statistics. No judge has ever established that they are the fathers or how much they should be paying. Child support offices can’t enforce debts that haven’t been legally established.

Allison Elizabeth Hines was born April 4, 1984. That December, the Buncombe child support office filed suit against Tommie Allison on Hines’ behalf through the courts in Summit County, Ohio.

Authorities in Ohio served Allison with a copy of the lawsuit demanding support, but when he got to court, he denied that he was the father.

Hines says that in her case, a blood test was never performed.

“They told me that because he was out of state, they couldn’t do that,” she said.

Ken Camby, who is now head of the Buncombe child support office, said it appears from his office’s files that child support workers should have filed a legal action to establish that Allison was the father before they filed a lawsuit seeking support.

The case closed for a time, but the office filed suit again against Tommie Allison in February 1993, again alleging that he is Elizabeth’s father.

A sheriff’s deputy in Ohio returned that lawsuit undelivered. Allison had moved, court records say.

The Citizen-Times obtained in March a current street address for a Tommie Lee Allison in Cincinnati from records maintained by the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Camby said his office’s records indicate several unsuccessful attempts have been made to find Allison since 1993. “We do try, believe it or not.”

Hines has a hard time believing that the authorities can’t locate Allison and force him to pay.

“You’re trying to tell me that someone who lives in the United States, with all the computer records . . . you can’t find him?” she said.

The System

Penny Porter relied for years on the efforts of the Buncombe County Child Support Office to track down her ex-husband and make him pay support.

But workers told her time and again that they couldn’t find Britt Shenkman after he skipped town in 1982, already owing more than $26,000 in past due support and alimony.

So when Porter joined a group for custodial parents called the Association for Children for Enforcement of Support (ACES) 10 years later, she only included an extra $5 for its “parent locator” service as an afterthought.

In eight days, an envelope containing five recent addresses for Shenkman was in the mailbox at Porter’s Arden home.

In about three months, $71,700 in past due child support and alimony payments was sitting in Porter’s bank account. Her son was 21 years old.

Most custodial parents don’t collect large payments all at once as Porter did.

But in one important aspect, her story is all too typical of those millions of parents seeking help raising their children — the system failed her.

Things Fall Apart

The nation’s child support enforcement system is burdened with rapidly growing numbers of cases; technology, laws and a work force that have not kept up; and a job that probably wouldn’t be easy no matter how well prepared the system was to do it: making people who are often hundreds of miles away pay money to a former lover or spouse.

The federal government requires states to operate offices to help custodial parents locate absent parents, get court orders requiring parents to pay, and keep the payments coming. Parents who receive AFDC are required to use the offices’ services, and the offices will help other parents needing support who pay a small fee.

While the child support enforcement system nationally added about 9,700 workers from 1989 to 1993 — a 27.6 percent increase — the number of cases in the system grew by 5.2 million, a 44 percent increase.

That works out to 382 cases per person employed by the system nationwide. But because many of those employees are either supervisors or clerical workers, it is not unusual for an individual case worker to be responsible for 600 to 1,000 cases or more.

North Carolina has traditionally been somewhat better staffed than the nation as a whole, with 373 cases per employee (including supervisors and secretaries). Even so, figures from early 1994 showed that the typical child support case worker had 685 cases to contend with. With that caseload, a worker would have to work for more than four months before he had spent one hour for every case he is responsible for.

Anger over child support enforcement has turned the words “deadbeat dad” into a national catch-phrase. But that anger has not always been turned quickly into action.

“The legal system is a very slowly changing institution,” said Buncombe County District Court Judge Gary Cash. “We proceed in certain respects as we have for years and years.”

All by Myself

Penny Porter says she went on welfare for two weeks in the mid-1970s, shortly after Congress authorized the child support program, for the sole purpose of enlisting the help of the Buncombe County office.

During all this time, Porter said she asked nicely for help and was told everyone was doing the best they could.

The letter [from ACES] changed all that. ACES had tapped into the records of a credit bureau to get Shenkman’s address.

“I was Miss Nicey for 19 years. Then when I found out that (the Buncombe office) was sitting down there doing nothing . . . I didn’t care what they thought about me. . . . I was the squeaky wheel,” Porter said.

Camby said his office’s files show “extensive” efforts were made to find [her ex-husband]. They just weren’t successful.

Porter doesn’t believe it. Buncombe workers “can’t be doing their job,” she said.

She’s glad to have the windfall, but figures in many ways it came too late. The home where she raised her son and two older daughters by a previous marriage was paid for largely through her parents’ generosity.

Without them, taxpayers “could have been supporting my kids. They wouldn’t have had a dime,” she said.

Excerpted by Priya Giri.

Tags

Mark Barrett

Asheville Citizen-Times (1996)