If It Don’t Fit, Don’t Force It!

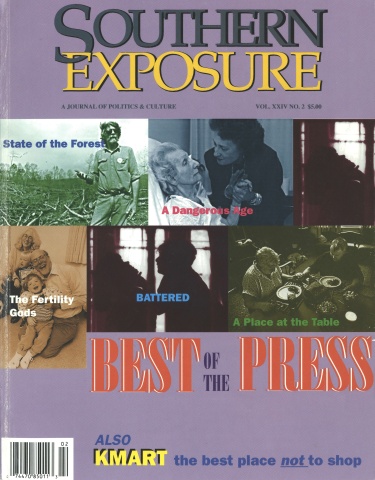

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

Did you ever have the feeling that you’re trying to get the right key in the wrong keyhole?

It was cold in Chicago. The Hawk was coming in off Lake Michigan like someone had kidnapped his three youngest children, and he was going to turn over every brick and shingle till he found them. The temperature was only about 38 degrees but the wind chill took it way down below freezing.

It had been years since I’d had to deal with “The Hawk” in “The Windy City.” Now here I was fighting the Hawk again for every inch I gained on Michigan Avenue. We were already three days into spring, and still another snowstorm was heading in. A few scattered flakes had already begun to curl around corners and people’s heads as we fought to reach the places that we had to go.

So what’s the big deal, right? Chicago’s often cold and always windy.

For me, on that day, it had to do with memories. Memories that cut as sharply as the wind did. Memories like the wind that seemed to cut past the bone into the marrow. I had lots of memories about this toddling town. The deepest cut came from the recollection of my old buddy, Po Tatum. I hadn’t been back to Chicago since 1968 when Po had disappeared after a showdown with the cops over some abandoned buildings he’d squatted in and was trying to renovate with a group of homeless ex-cons he had to organize.

I tried to find some of Po’s old running buddies on the South Side but didn’t have much luck. Johnny Tadlow was long gone — everybody thought he’d been wiped out by the Mafia as a warning to Po to get out of the food business. (Po and his crew were doing well raising and selling fresh homegrown vegetables in the neighborhood). Ms. Consuela LeBeaux (the nurse that Po used to live with) had moved back to Haiti right after Po’d disappeared and we’d had the memorial service for him. There was no way to track down Hound Dog and Dead Eye. I didn’t even know what their real names were. But I did hear about a popular blues club in the Old Town section called Flukie’s Place that they said was run by a fancy-dressing woman who always wore blue dresses. There’s a good chance that she’s the same woman that brought Po to his mama’s funeral back in ’51, but I couldn’t get to the club to check it out.

I had come back to Chicago to do some workshops with a Chicano community organization that’s working out a way to use the sharing of stories to build a coalition with some African-American groups there. I’ll tell you more about that story some other time, but this particular morning I was going to meet a good friend of mine who was in town for a meeting of the Theater Communications Group (TCG), the national organization for what they call “regional theaters.” Since this would be the only chance I’d have to visit with her, and since I always enjoy spending time with creative people, I thought that this would be a good fit. Besides, I was getting really frustrated trying to find Po’s gang.

When we finally got to the Goodman Theater where the meeting was, they had lots of fairly good coffee and sweets set out for those who had missed breakfast. Judging by how fast those things went, it must have been a good bunch of us. This I took as a good sign of things to come. Good coffee, good food, and good people often go together.

The main subject of conversation was how the regional theater movement should deal with the loss of income since the federal government’s trying to back out of the art business (like it’s backing out of a lot of things that don’t show up as short-term profits for big companies that pay for most of the talking done in Washington, in and out of those famous smoke-filled rooms). The government is sort of like Bill Cosby’s pal, “Fat Albert.” When Fat Albert jumps in the pool, it changes the game for everyone.

Once again I thought, “This is a good sign. They have the same problems as people who’re trying to go to school, old people with fixed incomes, people who need health care, people who work for a living, women who need equal pay and law, poor people, people of color — including, of course, those who are nearest and dearest to me, African Americans!”

Things started off pretty good. The group had just recently hired a new director, and this was a chance for them to get to know him and vice versa. The new director started out giving a short history of his own interest in the work and a brief background of the problem. “The problem,” he said, “is that there’s a breakdown of the cultural consensus on which the regional theater movement was based. That consensus was,” he said, “that (according to one of the founding fathers) the regional theaters should be valued more as centers of culture than as the producers of products to be bought and sold.”

“So now,” I’m thinking, “we know how they see the difference between ‘regional theater’ and Broadway/commercial theater, but what’s their idea about how theater relates to the rest of the world? How was consensus built in the first place? How come the discussion leading up to the so-called ‘consensus’ was limited to middle- and upper-income white people, mostly men?” It reminded me of the guy who said, “Let’s go back to the beginning . . . where I come in.”

If the core problem is how to deal with cutbacks in public funding for the nonprofit arts, then you have to take up the public debate about the value of art, which for the past several years has been led by those outstanding senators from the Carolinas, Jesse Helms and Strom Thurmond. Now that they have back-up from the GOPAC congressional freshmen, they’re really dangerous. All day, I waited to see when the discussion would come to the big question. “How do we mobilize our troops for counter attack?” Finally, my patience wore out my jaw strap. I had to say something.

Taking the privilege of a guest, I got permission to speak, and said, “Seems to me we’ve been losing chickens, geese, ducks, and all kinds of small critters from barnyards all over the country for a good while. Now we’ve got a couple of greedy, old, no-count, broke-down foxes volunteering to head up the troops that’s going to guard the barnyard. From what I understand about what y’all say you’re supposed to do, TCG is well-suited to take the leadership in the national discussion about the role of art in American culture. Maybe that should be the main thing you do for the next few years, at least till things get turned in the right direction.”

They looked at me like I had taken my clothes off and cussed at the preacher in the church house. After a while, they went on with the conversation as if I hadn’t said a thing at all. I looked at my friend who’d brought me over there and hunched my shoulders. She hunched back, and we listened to them as they kept on talking about how each organization could better itself without fighting those old fat foxes, Helms and Thurmond.

All I could think of was what James Baldwin told Angela Davis when he volunteered to help keep her out of jail: “If they come for you in the morning, they’ll come for me at night.” Helms, Thurmond, and company have practically killed the National Endowment for the Arts. They’ve got the Smithsonian Institution scared to make honest historical exhibits. What will stop them from marching in the front door of any theater in the country and closing it down next?

After the meeting was over, my friend and I had The Hawk to our backs as we headed back down Michigan Avenue. The wind was even more fierce than it had been that morning. I told her “Well, I’m pretty sure that I had the right key, but I guess I was trying to stick it in the wrong keyhole.”

“Humph!” she said as if the Hawk had taken her breath when she opened her mouth to talk. “If it don’t fit, don’t force it.”

“I wish I’d been able to get Po Tatum that message when he was holed up in that building on Drexel Boulevard.”

“Potaters?”

“No, I was talking about my homeboy, Po TA-tum. If you’ve got the time for a drink, I’ll tell you about him.”

Tags

Junebug Jabbo Jones

Junebug Jabbo Jones sends along stories from his home in New Orleans through his good friend John O’Neal. (1994-1997)

John O'Neal

John O'Neal was a co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater for almost 20 years. He is currently touring the nation in his one-person play, Don't Start Me Talking Or I'll Tell Everything I Know: Sayings from the Life and Writings of Junebug Jabbo Jones. (1984)

John O ’Neal is co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater in New Orleans. O’Neal’s one-person play, “Don’t Start Me to Talking Or I’ll Tell Everything I Know, ” is currently touring the country. (1981)