This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

The Florida chapter of the American Indian Movement (AIM) has declared war against those responsible for irreparable damage to the graves of American Indians. “If there is no respect for the dead, how can we respect the living?” asked Sheridan Murphy, executive director of the organization.

Archaeological and burial sites throughout the Southeast are ravaged from illegal activities. Looters, also known as “pot hunters,” commit their crimes in remote places that are hard to patrol. Witnesses are afraid to come forward because pot hunters are intimidating, carrying weapons and making threats.

Native Americans claim that desecration of their ancestors’ graves is acceptable because of racism. In 1989, a Kansas grocer made souvenir key chains from the pile of Indian bones he displayed behind his counter. There are other examples: a college prank by George Bush involved the theft of an Indian skeleton. An Iowa road crew discovered the bodies of 26 whites and two Indians; the whites were reburied immediately, but the Indians were turned over to a museum.

Susan Shown Harjo with the Morningstar Foundation said in a 1991 report, “Everyone gets the right to be buried and stay buried. That’s the rule throughout the world. The rules change when it comes to Indian country.”

When the United States and Great Britain failed to ratify a UNESCO treaty that would have prohibited the export of human remains and burial objects, looters saw an opportunity. Markets pay top dollar — a Southwestern pot brought a quarter of a million dollars and a Mississippi ax sold for $150,000 — and create a feeding frenzy at sites throughout the United States.

Out of 950 million acres of federal land, less than 10 percent has been surveyed for archaeological sites. When looters find these sites first, archaeologists worry that important information is lost forever.

That was the case at yhe Yat Kitischee (Red People) site in Clearwater, Florida. Despite being in a residential and industrial area of one of Florida’s most densely populated counties, the site had remained unknown to area archaeologists — but not to looters who destroyed acres of village and burial sites.

“The media didn’t care what was happening until we took up arms to defend [Yat Kitischee]. That got everyone’s attention,” said Murphy.

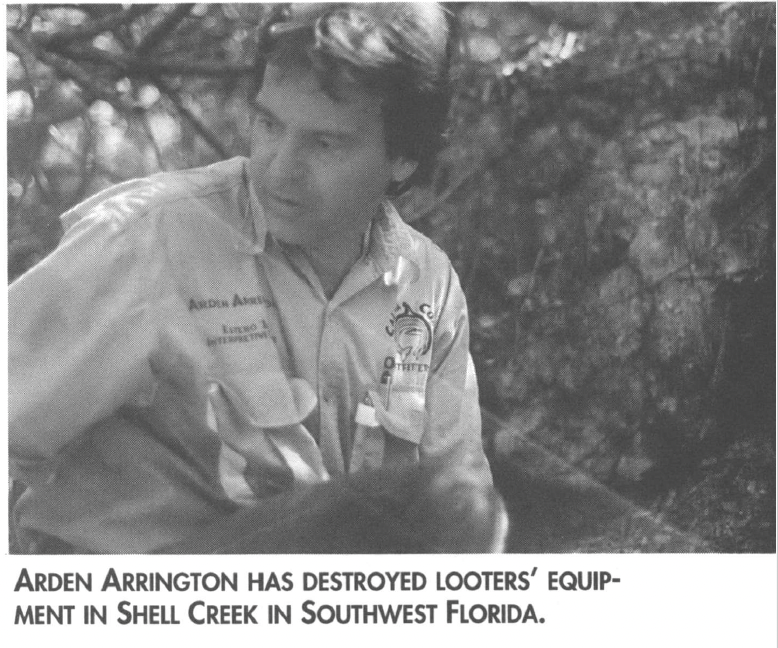

Although Yat Kitischee has been saved from further vandalism, other sites like Shell Creek in southwest Florida are not so lucky. This ancient Calusa village is mined often and now has 40 holes, some nine feet deep. Bone fragments and teeth are exposed to the surface.

Local nature guide Arden Arrington has destroyed looters’ equipment left at Shell Key, leaving pieces hanging in trees as a cryptic warning. But these efforts have had little effect. “We’ve all spent lots of time and money trying to get this stopped,” Arrington said.

In 1986 Florida passed the Unmarked Bodies in Graves Law to protect Native American graves. Ten years later, Native American activists accuse the state of failing to stand behind the law. Though trading in human remains is illegal in most Southeastern states a 1989 Baltimore Sun article estimated that “1.2 million individual Indian skeletons, along with countless bone fragments, grave goods and sacred objects, lie unburied in the hands of auctioneers, collectors, archaeologists, and museums nationwide. No one knows for sure how many Indian bones occupy the coffee tables and research laboratories [in Maryland].”

“Native American remains are the remains of human beings and should be treated that way,” said Joe Quetone, executive director of the Florida Governor’s Council on Indian Affairs. “They’re not pre-historic. They’re human beings.”

Tags

Lois Tomas

Lois Tomas is a freelance journalist and editor of Red Sticks Press, an American Indian newspaper in St. Petersburg, Florida. (1996)