This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

Fifteen years ago, if an advocacy group in the South want to find funding, they generally had to look to foundations in New York, California, or some other place outside the South. The few foundations in the region fund some community groups, but the bulk of their money goes to service organizations or more established, mainstream efforts.

In 1981, a group of Southern activists led by Alan McGregor, then of the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons, later of the Sapelo Foundation, founded a Southern-based funding source for organizations working for social change in the South — the Fund for Southern Communities.

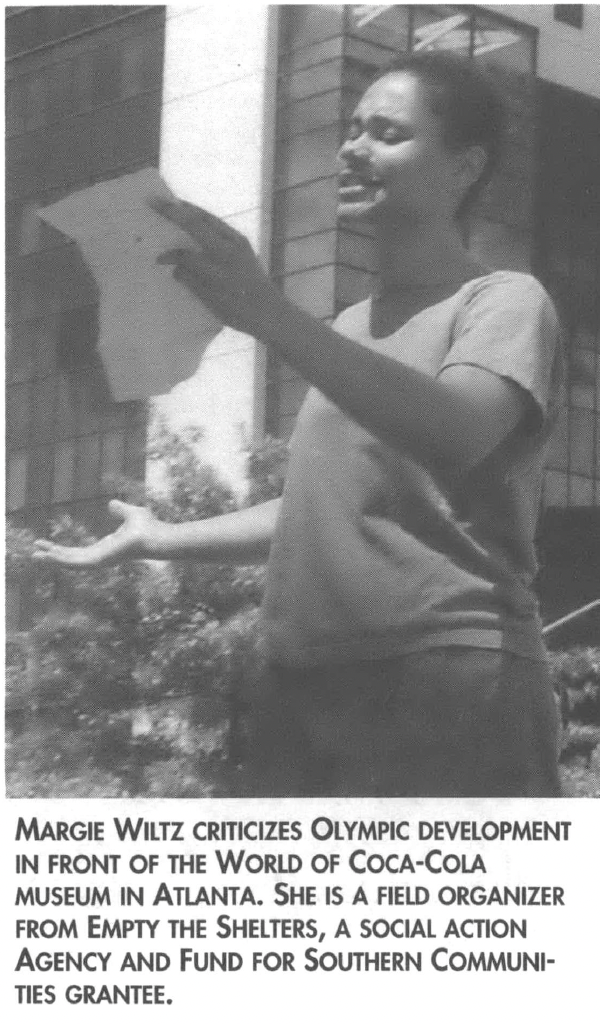

The Fund’s annual report shows an organization supporting populist if not popular causes. Last year they helped Empty the Shelters in Atlanta, a student-oriented group that works with the homeless and researches the impact of the Olympics on Atlanta’s low-cost housing. The Fund gave money to Concerned Citizens of Tillery in North Carolina to help the African-American farming community work with community development, land loss, and health issues. They also assisted Helping Hands Center in Siler City, North Carolina, in connecting Latino and African-American poultry workers with contract growers and environmentalists in economic, environmental, health, and safety issues. They gave money to the Prison & Jail Project in Americus, Georgia, to work with prisoners, their families, the media, and other advocates to demand fair treatment for defendants regardless of race and income level.

The Fund was one of the first organizations in the South to give money for gay and lesbian organizing. And with the help of member donors, the Fund recently established the Southern Outlook Fund, a special fund that has already given $100,000 specifically to assist gay and lesbian groups.

The Fund and donors have established other special funds as well. In North Carolina, the Triangle Fund helps organizations in Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill. In South Carolina, with a donation from the South Carolina American Civil Liberties Union, they established the Modjeska Simkins Fund. Named for a civil rights legend in South Carolina, this fund supports grassroots organizing in the Palmetto state.

How It Works

According to Joan Garner, executive director of the Fund, money and technical support go to grassroots and social change organizations in Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. Members of the 15-person board of directors represent community groups supported by the Fund.

Garner, who came to the organization five and a half years ago as a development associate, emphasized how the board structure makes the Fund different from other foundations. “With most traditional funding organizations, you have family members who sit on the board, or there is a certain group of donors who control the decision making,” she said. “Here, the grantmaking is made by individuals we support.”

Having activists as board members makes the Fund receptive to issues other foundations find controversial. “We talk to and fund community groups and issues that other foundations won’t even talk to,” Garner said.

Apply Yourself

Organizations seeking funding must work in North Carolina, South Carolina, or Georgia. The Fund supports groups involved in community empowerment, education, or organizing. Their work can include environmental issues, alternative media, women’s issues, and issues affecting people of color. The organization does not fund lobbying but will consider funding “a community that wants to go about making some long-term change in policy,” Garner said.

The small grants are significant. “Once organizations get funding from us, they can leverage it to receive funding from larger foundations,” explained Garner. Program officer Jack Beckford likes to point out that a small grant from the Fund paid for a feasibility study for the Self-Help Credit Union in North Carolina. Self-Help has become a multi-million-dollar model of community development lending, making loans for homes and small businesses that most banks would consider too risky.

The Fund is a small operation compared to many foundations. Garner said the organization makes 60 to 70 grants per year, usually of $3,000 or less. Even as a modest operation, they are far grander than they used to be: They give away a quarter of a million dollars a year. In their first year, they awarded 23 grants totaling $24,297. The Fund recently passed the $2 million mark in grantmaking.

The Fund also provides technical support for activists and donors. “We realize that in addition to providing funding there’s also a need to provide basic skills that go with building an organization — such as fundraising skills, management skills and board development,” said Garner. “We help identify programs or resource people that can provide skills.”

Members

The Fund for Southern Communities is different from traditional foundations in another way. It does not have an endowment. Most of its funding comes from donations from its members, many of whom contribute modest amounts. The rest of the funding comes from other foundations and an annual fundraiser featuring performing artists like Sweet Honey in the Rock. The fundraisers raise money but also provide an opportunity for members to network.

Garner sees the Fund becoming increasingly important given the political climate and cuts in federal funding. She also sees the Fund expanding its role of bringing in diverse segments of the population to philanthropy. “We have brought people into the field of philanthropy that really would not have access,” she said. “We’re also very instrumental in helping to reform philanthropy in terms of who makes decisions.”

Having people of color, grassroots activists, and other disenfranchised communities make decisions about who gets funding makes sense, Garner said. “They know who’s doing the work in their community and who isn’t.”

Tags

Alvin A. McEwen

Alvin A. McEwen is an Associate Editor with the South Carolina Black News in Columbia. (1996)