The Fertility Gods

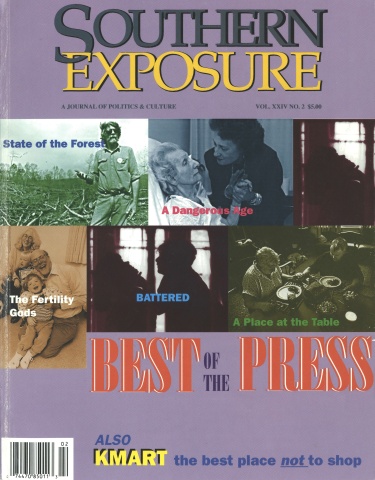

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

Messing with Mother Nature! Will She strike back? In this three-part series Carol Winkelman, a freelance writer and science editor, describes the joys and dangers of a recently developed fertility treatment that uses eggs of a young woman to implant in another woman. In her meticulously researched series, Winkelman describes the complex egg donation procedures, examines informed consent procedures that experts deemed inadequate for egg donors, and looks at ethical dilemmas that arise with the new techniques.

Shortly after her series appeared, the Assisted Reproductive Technologies clinic, (which is affiliated with both University of North Carolina Hospitals and the medical school) improved their informed consent procedures.

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — The last two and a half years of Dion Farquhar’s life read like a fairy tale. She fell in love, married, had twin boys, and signed a book contract with a classy New York publisher.

But hers is a modern fairy tale. Both the boys and the book came to her as the result of the most recent and most successful of the high-tech fertility treatments available at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — egg donation, a process by which eggs from one woman are surgically removed, fertilized, and transferred to another woman’s uterus.

After the eggs were donated by a 25-year-old woman, fertilized in a petri dish and transferred to her uterus as 2-day-old embryos, Farquhar became pregnant at age 45. At 46, after a normal pregnancy, she gave birth to twins Alex and Matthew.

Farquhar’s late-in-life pregnancy reflects the success of UNC’s egg donor-recipiency program, in which previously infertile women now can have babies thanks to idealistic young women, many of them students who contribute their eggs for $1,500 and a feeling of altruism.

The egg donor program, the most successful part of UNC’s assisted reproductive technologies program, currently offers patients a 39 percent “take home baby” rate — one of the highest rates in the country. Duke University Medical Center’s take home baby rate is 33 percent, and the large and well known University of Southern California program has a take home baby rate of 31 percent.

But there may be a price for that success.

Are we to be charmed by heartwarming stories, dazzled by new technology, or unsettled by unforeseen consequences?

It is too early to tell; egg donation is only 10 years old. For recipients, at least, benefits outweigh risks, and the news is hearteningly good. Women who previously could not have babies, now have babies — sometimes two or three — thanks to the strides made in obstetrics, cryogenics, and embryology over the last 20 years.

In the 1970s came the fertility drugs that stimulated egg production and gave women more chances to conceive a child. In the 1980s, there was the evolution of high-tech fertilization — IVF (in vitro fertilization), GIFT (gamete intrafallopian transfer), ZIFT (zygote intrafallopian transfer), and finally egg donation.

Since the first donor-recipient baby was born in 1984, egg donation has become an increasingly popular high-tech way to have a baby, with a success rate that now surpasses all the other assisted reproductive technologies.

In 1993 alone, egg donation resulted in the birth of more than 1,000 babies. From 1992 to 1993, the number of egg donor-recipiency programs reporting to the American Fertility Society increased from 75 to 137.

The UNC program, developed in 1990 by Dr. Luther Talbert, who is now in private practice in Cary, is one of the older and more successful programs. It has performed over 107 transfers of eggs from donors to recipients resulting in 36 successful pregnancies and, since many were multiple births, 56 babies in all.

The Donors

One of the secrets of the UNC program’s success lies in its youthful donors and their young eggs. It was UNC’s reputation for a “plentiful supply of healthy donors” along with its success rate that prompted Farquhar’s New York doctor to send her to Chapel Hill in the first place.

“The Chapel Hill area has a near optimal donor population,” says Dr. Mark Fritz, chief of UNC’s Division of Reproductive Endocrinology, of which the fertility and egg donor-recipient programs are a part. Many of these women are college students who present fewer concerns regarding AIDS, hepatitis, drug and alcohol abuse, and other health problems than donors from urban centers like New York and Los Angeles.

“It’s difficult to get good donors,” said Dr. William Meyer, director of the UNC program and assistant professor of gynecology at the UNC Medical School. “In New York City, you have a problem because if you run an ad in the newspaper for $2,000 for egg donation, you’re going to get people who are maybe not the best people to get donated eggs from.”

UNC targets its advertising at students by running ads in The Daily Tar Heel that offer potential egg donors $1,500 per completed egg donation cycle. In order to qualify, donors must be between the ages of 18 and 32. They must also pass through a medical and psychiatric screening process.

The Recipients

Women seeking donor eggs at the UNC clinic may be as young as 25 or as old as 50.

Though Meyer says the program prefers to “offer a service within the bounds of what might occur naturally,” menopause is not necessarily a limiting factor. Some recipients are young women in their 20s or 30s undergoing premature menopause. Young women with genetic defects, inherited diseases or eggs damaged from chemotherapy also turn to egg donation as their only chance to bear healthy babies.

But the majority of egg recipients are women in their late 30s to mid-40s who have been unable to get pregnant or stay pregnant using other infertility treatments. Women in their 40s receiving donor eggs have higher take-home baby rates and lower miscarriage rates than women in their 30s undergoing in vitro fertilization or intrafallopian transfers with their own eggs.

What recipients have in common is not age or marital status but a strong determination to have a baby and the ability to pay for $13,000 worth of drugs, lab tests, and medical procedures, since they are responsible for both the donor’s and their own medical expenses. Few insurance companies will pick up the tab.

What Cancer Risk?

When an egg donor walks into the UNC Assisted Reproductive Technologies clinic, she thinks about how donating eggs will help an infertile couple have a baby. She thinks about how the $1,500 will boost her budget or pay her student loans.

She doesn’t think hard about long-term cancer risks.

She should, according to recent biological theory. Egg donors take fertility drugs to push their ovaries to produce from five to 30 eggs instead of the usual one or two per menstrual cycle — and the more a woman ovulates, the greater her cancer risk.

But the UNC program, along with others around the country that are dependent on young donors to maintain their success rates, describes the cancer risk in language that experts say is inadequate.

“I am astounded by the lack of informed consent,” said Bernadine Healy, former director of the National Institutes of Health under the Bush administration. She is currently Senior Health Policy Advisor at the Cleveland Clinic. Informed consent is a vital legal and ethical doctrine requiring a doctor to provide patients with the information they need to make decisions in their best interest.

“Egg donation should be treated with the same care as research. It’s a high stakes activity that should get as thorough an informed consent as possible in medicine,” said Dr. Arthur Caplan, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Bioethics, who has seen problems with consent forms at several university fertility centers. “UNC,” Caplan said, “downplays the risks donors are taking instead of providing an explicit discussion of them.”

But the fertility doctors are in an awkward position: If the information they hand out dissuades potential donors from giving, the doctors’ fertility patients — and much of their $300,000 program — suffer.

Some suggest that’s a conflict of interest, and that the job of informing potential donors should be left up to other doctors completely detached from the program.

“You don’t have to be a conspiracy buff,” Caplan said. “There is a tremendous shortage of eggs and egg donors and a lot of money to be made, and I think people are trying hard to get donors.”

UNC Hospitals’ program is not a money maker as it is in some hospitals. In 1993-94, in fact, the program lost $142,000, not including doctors’ fees. In 1994, there were 18 egg donors, and 13 women gave birth with donated eggs.

Meyer said the clinic gives adequate warning of risks and tells donors “the bad aspects of donating.”

“At best, they really try to discourage you,” said Tonya, a 20-year-old woman who donated eggs at the end of her 1994 freshman year at UNC. “What they tell you would scare a lot of people off,” said “Tonya,” who has asked to remain anonymous.

A Questionable Practice

An hour-long donor-education class tells possible donors at UNC about weeks of hormone injections, medical tests, and monitoring of ovulation, as well as descriptions of the drugs and medical risks involved in the egg donation process.

But the long-term medical risk of ovarian cancer is mentioned only briefly, and in what some experts say may be in misleading and confusing ways:

■ No mention is made of the risk of ovarian cancer on egg donor risk sheets and consent forms.

■ No mention is made anywhere of the most recent and worrisome 1994 findings that showed an 11-fold increase in cancer risk.

■ The ovarian cancer risk is mentioned — and diminished — on a reprint of a medical article by Dr. Richard Marrs that calls the findings of a 1992 study on fertility drugs and ovarian cancer “meaningless from a clinical standpoint.”

This information does not give egg donors a balanced view of the ovarian cancer question to make informed decisions in their own best interest, according to some health policy experts.

Giving the Marrs article to donors without giving them articles representing the other side of the medical debate is what Healy finds “a questionable practice.” In an editorial in the May issue of the Journal of Women’s Health, which she edits, Healy wrote: “It is disconcerting that some fertility specialists are ready to discount the cancer risk and, at times, provide egg donors with ‘reprints’ which dismiss, if not discredit, the recent epidemiologic data.”

Marrs said in an interview that his article is being misused if given to patients with the intended message that “you don’t have to worry about this.”

“If they take what I wrote and give it to their patients and say, ‘Here is the truth about this’ — this is not what I wanted,” he said.

Ovarian cancer is a nasty disease. Although a woman’s lifetime odds of developing ovarian cancer are low, about 1.5 in 100, her odds of dying once she gets the disease are relatively high. Because ovarian cancer is silent and difficult to detect, it is fatal 60 percent of the time within five years after diagnosis, according to the Center for Health Care Statistics. Breast cancer survival rates after five years are twice as high as survival rates for ovarian cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Opinions vary on how to interpret the potential risks of fertility drugs. Dr. Mark Sauer, one of the pioneers in egg donation as former head of the donor-recipiency program at the University of Southern California, said the risk is probably small. But small is a relative term.

An increased risk to even 4 in 100 is “not a trivial number, especially if you are one of the four,” said Dr. Alice Whittemore, professor of epidemiology at Stanford Medical School and author of a controversial 1992 study.

Ethical Dilemmas

When Stan Beyler holds one of his patients’ babies in his arms, chances are he first saw that baby as a few cells under a microscope, and first held it as a fertilized egg in a petri dish — or a frozen embryo in a cartridge-shaped tube. For Beyler, this is humbling.

Beyler, the embryologist at UNC’s Assisted Reproductive technologies clinic, sees himself not as a fertility god but as “his or her handmaiden,” who assists nature by helping couples overcome physical obstacles to pregnancy.

But, while fertility specialists may stand in awe of nature, they are in control of a technology that has ramifications we can barely imagine.

They freeze embryos for future use, keeping them for years in suspended animation until brought to life or discarded. They make previously infertile women pregnant — sometimes with twins or triplets.

But can our laws, ethics, and psyches keep pace with these rapidly developing technologies? Is science pushing nature too far?

Some embryos are never transferred to a uterus. They are frozen, discarded or used for research, depending on individual agreements between doctors, hospitals, and clinics. An egg donor may produce as many as 20 eggs. Once fertilized, there’s no telling how many of those will become healthy embryos. If four are transferred to a recipient woman, what should become of the rest?

Should such embryos be frozen indefinitely until the recipient wants to become pregnant? Or should they be discarded, given to someone else or donated to research if no longer needed?

“The morass of unknown ethical dilemmas with frozen embryos is a bigger issue than most things,” said Sauer. It could result in legal entanglements involving inheritance, custody — even embryo theft. According to current American Fertility Society guidelines, embryos should be kept no longer than the reproductive life of the woman who donated the egg, which would prohibit the transfer from generation to generation.

But it is possible for triplets, identical or fraternal, to be frozen at the same time, thawed in different generations, carried by different mothers — and born decades apart.

If cloning is ever considered acceptable, women could give birth to identical twins generations apart. Theoretically, a woman could give birth to her grandmother’s eggs frozen decades before. And if unfertilized eggs are ever successfully frozen, a woman could utilize eggs frozen decades before.

Cloning could be clinically practical, said UNC’s Beyler, if used to increase a woman’s odds for pregnancy. “You could clone an embryo to become two, three, or four embryos to enhance her pregnancy rate,” he said.

UNC’s Beyler says that assisted reproductive technologies will stay within the bounds of what the individual society dictates. “But this will vary from culture to culture — and from generation to generation,” he says.

“What we consider abhorrent now,” he said, “may be acceptable in 100 years.”

In July 1995, one month after this series appeared in The Chapel Hill News, the UNC fertility clinic strengthened the ovarian cancer warning it gave to egg donors.

The changes were made in the “informed consent” form given to egg donors to tell them of the possible risk of drugs and procedures involved in egg donation. The clinic now warns potential egg donors that an association may exist between ovarian cancer and fertility drugs and that multiple donations might increase this risk. Along with this warning, donors are offered birth control pills following their donation since these pills may reduce a woman’s risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Changes were also made in the accompanying information given to donors to explain the possible ovarian cancer risk. The clinics substituted a one-page paper that dismissed the cancer risk with a longer and more recent medical paper.

Previous critics applauded the changes. Dr. Arthur Caplan, director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, said that UNC was “moving in the right direction” because the added information empowered egg donors to ask questions.

But problems still remain, according to Caplan and other experts in the field. The new paper on risk that the clinic now provides to donors is, like the one that preceded it, dismissive of cancer risks. It was also commissioned by the pharmaceutical company that manufactures the fertility drugs given to egg donors — but that fact is never revealed to donors. The author of the paper, Dr. Howard McClamrock, says he doesn’t give his paper to egg donors at his Maryland clinic because “it was not peer reviewed and accepted for publication. It’s my position, and my ideas only — not any more than that.”

Excerpted by Sally Gregory.

SIDEBAR

Other Winners Division Three (dailies with Sunday circulation of under 30,000): Second Prize to Lenora Bohen LaPeter of The Island Packet on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, for a series that exposed chronic abuse in local nursing homes and another series on the destruction of once-fertile oyster beds by rapid development. Third Prize to Wister Jackson of The Daily Courier in Forest City, North Carolina, for his expose of a local church that turned its members into indentured servants who toiled in factory jobs for the benefit of church leaders.

SIDEBAR

Tests, drugs and $1,500:

Some egg donors would give again— and some wouldn’t

Chapel Hill — It all started with a tiny ad in The Daily Tar Heel.

The ad offered $1,500 for young women willing to donate some of their own eggs to women who couldn’t have children.

Tonya, a 20-year-old pharmacy student at the University of North Carolina, thought it would be wonderful to help someone have a baby. And she could use some extra money to help put herself through college.

The donation meant going through medical, genetic, and psychological screening tests and then adhering to a demanding regimen of hormone injections and medical tests. Tonya donated eight eggs last July to the UNC egg donor-recipiency program. And she plans to donate eggs again.

Tonya says the UNC clinic “did a great job” of walking her through the egg donation experience, warning her of the risks of infection from the egg retrieval procedure, and telling her about ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome — a short-term risk of the fertility drugs that may cause ovarian swelling and abdominal bloating and tenderness. But Tonya said a possible long-term side effect of the drugs, ovarian cancer, was only briefly mentioned.

An aspiring pharmacy student, Tonya read up on the drugs at the UNC Health Sciences Library. She also sought the opinion of her family doctor. After he told her she was young, healthy, and not at high risk for side effects, she decided the benefits of donating were worth the risks.

Although Tonya says she wants to be “as emotionally unattached to the eggs as possible” and says the real mother is the woman who carries the baby for nine months and becomes attached to it, she says she would sacrifice her anonymity if doing so would help the child. “If the child needed a kidney or something, I would donate,” Tonya said, “if it were between my own child and that child, I’d pick the child that I’d carried. . . . But I’d want to be notified and asked. The parents could notify the infertility clinic, and they could notify me.”

Such altruism is common in the UNC donor population, said Robert Bashford, the UNC psychiatrist/gynecologist who screens women for the program. “This kind of procedure attracts a certain kind of creature,” Bashford said. “They give blood and plasma. They carry an organ donor card. That’s who comes through the door.”

Another young donor, a 20-year-old from Durham who asked to remain nameless, gained insight into the pain of childlessness by talking with infertile friends. “That’s what made me decide. I knew how bad they wanted children,” she said.

But she doesn’t plan to do it again. The fertility drugs’ side effects gave her sore thighs, mood swings, and a belly so bloated she looked and felt pregnant. “My leg got numb from Pergonal. I got so bloated I couldn’t wear clothes. My stomach got real hard in places,” she said. “I was very emotional, with cramps and all. It was like PMS — only 20 times worse.”

The UNC clinic prepared her well for the egg donation experience, she said. She was taken by surprise only once — by the pain following the egg retrieval procedure. “After surgery, I was in so much pain I couldn’t lay down or sit down. It took about a week. I looked pregnant, I couldn’t even walk straight,” she said.

In the ultra-sound-guided egg retrieval process, a long needle is passed through the vaginal wall to harvest eggs from the ovaries. She produced 22 eggs and “gave a baby back to the world,” as she had hoped to do, since the recipient couple got pregnant. “I felt good that I had helped somebody,” she said.

Unlike Tonya, she decided not to donate again. “I wouldn’t want to go through that pain again,” she said. “I helped one couple out. I don’t need to help everyone in the world.”

SIDEBAR

“The bottom line is, you’ve got this cute kid.”

Like many women of her generation, 48-year-old Dion Farquhar postponed childbearing while she pursued her education and career.

As the first member of her family to go to college, Farquhar was a serious student. She earned a Ph.D. in political theory, taught college for several years and then, in her late 30s, was ready to have children.

She looked for the right man — but didn’t find him. Finally, at age 42, with her child-bearing years waning and no permanent relationship in view, Farquhar decided to have a baby on her own.

After two and a half years of fertility treatments, starting with low-tech artificial insemination and ending with higher-tech fertility therapies, Farquhar was about to give up on having her own biological child.

Then her New York doctor told her about egg donation: “She told me, “You get the egg of another woman, and they fertilize it in vitro and put it in you, and you gestate it — and you have the pregnancy experience,’” Farquhar said. “And that appeals to me as a kind of hybrid between adoption, in which I would have no genetic connection to the child, and having my genetically own baby.”

Farquhar’s acceptance into the UNC program was followed by a serendipitous chain of events. Farquhar left New York for a summer seminar in Santa Cruz, California. What began as a dinner date five days later with Marsh Leicester, 53, an English professor at the University of California Santa Cruz, led to marriage within three months. “We met for dinner — and that was it,” Farquhar said.

Meanwhile, Farquhar started the hormone injections that would prepare her uterus for the implantation of an embryo and waited for UNC to find an egg donor. That August, while vacationing in Michigan, Farquhar got a call from Linda Bailey, a nurse at the UNC program, with good news: They’d found a donor match who would be ready to go in mid-September. The bad news was that Marsh could be the sperm donor only if he and Farquhar were married.

Three days later, Farquhar and Marsh tied the knot on the shores of Lake Michigan.

By September 19, Marsh and Farquhar were at UNC to participate in a conception in which neither of them would be a genetic parent. Marsh, at 50, produced sperm that could not fertilize the donor egg.

Fortunately, the couple had arranged for “donor back-up” from the sperm bank.

After the eggs were fertilized and incubated, four good embryos were transferred to Farquhar’s uterus. Twelve days later, Farquhar’s pregnancy test came out positive. She was having twins. After a normal 39-week pregnancy, just one week short of her due date, Farquhar gave birth to fraternal twins, Alex and Matthew.

Farquhar plans to tell the boys of their unusual mode of conception when they are older. “All the close people know, “ Farquhar said. “Nobody has been appalled. . . . The bottom line is, you’ve got this cute kid. That’s what people see, not the abstraction of biogenetics.”

Unlike some of the recipients, Farquhar did not bond with her anonymous donor who, Farquhar feels, gave “an abstracted part of her body — her genetic material. I wasn’t particularly interested in whether she swam or played chess. . . .

“You’d think I’d be more worried,” Farquhar said, but she accepted the UNC team’s judgment that the donor was a good match in terms of height, weight, and hair color.

As far as Farquhar is concerned, the children are hers. “Bonding is just bonding,” Farquhar said. “I couldn’t imagine being closer to them or loving them more.”

A part-time lecturer at the University of California, Farquhar was asked to give a talk on some scholarly topic that she was working on. “So I said, ‘I guess I’m working on reproductive technology.’” Farquhar’s paper developed into a book, The Other Machine: Discourse and Assisted Reproductive Technology, to be published this year by Routlege of New York.

Tags

Carol Winkelman

The Chapel Hill News (1996)