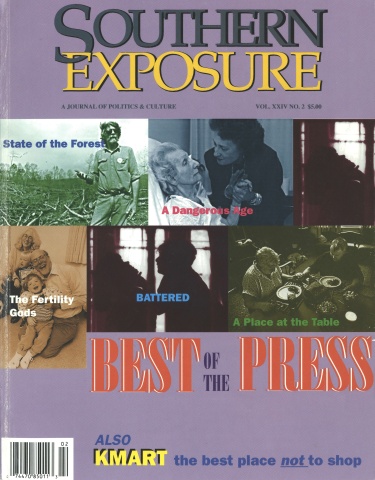

A Dangerous Age

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

St. Petersburg Times reporters Carol A. Martin and Stephen Nohlgren suspected that some elderly Floridians were falling prey to psychiatric hospitals desperate to fill beds. The expose that resulted from their 18-month investigation detailed how hundreds of old people were committed against their will for treatment they did not need. “A Dangerous Age” informed Florida’s citizens about a scandal, protecting many of them from falling victim themselves. It also prompted a crackdown on psychiatric hospitals that commit elderly patients against their will for unnecessary treatment.

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. — A locked-down psychiatric hospital was the last place you’d expect to find Mary Whelan. She wasn’t about to slash her wrists, wander aimlessly in the street or climb a tower with a gun.

She was 97, weighed 90 pounds, and lived in a South Pasadena nursing home. At worst, she hated showers and sometimes refused medicine.

In earlier times, the community would have respected her wishes and accepted her eccentricities. But not these days. Whelan carried a Medicare card. And that made her a treasured commodity in mental wards, where beds need filling.

Last year, despite her daughters’ objections, Whelan was locked up in Clearwater’s Horizon Hospital for two weeks until a judge set her free. In the nursing home, Whelan had been active and happy, her daughter says. In Horizon, she was “so drugged she could not keep her head up to eat her dinner. She just wanted to go to sleep. It broke my heart.”

In the last few years, as private insurance companies cut payments for psychiatric treatment, some hospitals and doctors have found a bountiful source of relief: old people. They may not need to be locked up. Their families may resist. State law may create hurdles. But no matter. If old people refuse to cooperate, it’s remarkably easy to force them.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Pinellas County, “the commitment capital of Florida.” About two-thirds of the people forced into treatment in Pinellas in 1993 and 1994 were 65 and over, almost all of them white and more than half women. They came from all over the state.

Pinellas committed more mental patients than Dade County, which has twice the population. More people were locked up in Pinellas than in Duval, Orange, and Palm Beach counties combined.

The Times compiled these figures after getting court orders to examine two years of commitment files — more than 4,000 cases. Reporters also interviewed scores of families with first-hand experience. The research reveals a disturbing pattern of financial conflicts of interest, questionable practices, and sweeping power:

• Mental hospitals locked up people who didn’t belong there.

Florida’s Baker Act, which permits forced treatment, is designed for dangerous people or those who seriously neglect themselves. But nursing homes use the law to ship out people who are more unruly than dangerous, experts say. Some of the patients ping-pong between nursing homes and mental hospitals repeatedly. Creative care at the nursing home could manage many of the problems just as well.

In the hospitals, diagnoses can be based on misinformation and innuendo. Helen Tooker, an 88-year-old St. Petersburg artist, was diagnosed as depressed in part because she wouldn’t get out of her wheelchair at Horizon Hospital. No one at the hospital asked why. It turned out that drugs made her so dizzy she couldn’t walk.

• Those who stand to make money call the shots.

The court system is designed to protect the rights of people forced into mental hospitals, but judges and public defenders are swamped. They rely on the word of hospitals and doctors — who stand to earn money treating committed patients.

Family members can be shut out entirely. Renee Monsarrat, 90, of South Pasadena, was forced into Horizon Hospital on the word of a hospital marketer. Her son Peter, who lived in New York, would have taken his mother to live with him had anyone called. “The people down there knew she had a son,” he said. “Why do this without even getting in touch with me?”

• Hospitals and doctors exploit loopholes in the law.

When people need help, the law says they should go to the nearest state-approved psychiatric facility; but hospitals find ways to bring unwilling patients from afar.

Birddie Carson was sent 165 miles from a nursing home in Starke to the Manors, a Tarpon Springs psychiatric hospital, bypassing dozens of closer facilities. “I was strapped down on a stretcher, and it was an awful bumpy ride,” she said. “When I arrived, I couldn’t even stand up because of my arthritis.”

Don’t look for consequences. Commitment laws are vague and carry no penalties for those who abuse the law. The patient’s mental condition is usually the judge’s focus, not how the patient got to the hospital in the first place.

• Hundreds of people volunteer for treatment, which cuts off court oversight.

In fact, some people had no clue what they were doing, or they said they were pressured. When one St. Petersburg man was brought to a hospital for electroshock treatments, a doctor said he was a voluntary patient, but hospital notes describe him as uncooperative, angry, and depressed. He was shocked eight times.

• Forcing the elderly into psychiatric treatment can be deadly.

Take frail, old people away from familiar surroundings and feed them powerful drugs, and sometimes they die. When 79-year-old Richard Winter was taken 100 miles to the Manors, he became seriously ill within days. On his wife’s first visit, his teeth and glasses were missing, and he was wearing someone else’s clothes. He died two weeks later.

Other times, medical professionals are so focused on mental illness they overlook other medical problems. Ezra Davis, 78, was dying of stomach cancer and in severe pain. But at Horizon, he wasn’t given painkillers for eight days. His psychiatrist didn’t know he had terminal cancer, a hearing master suggested.

Growing Business

The elderly get committed in large numbers because they need psychiatric care, said officials at Horizon and the Manors, which force more patients into treatment than any other Pinellas hospitals. Both have large units devoted to the elderly and collected about two-thirds of their 1994 income from Medicare.

Patients come to the Manors because hospitals in other communities can’t match its geriatric care, said administrator F. Dee Goldberg. “We’re sitting in a very successful hospital in the state of Florida. And the reason it’s successful, a hundred percent of the reason it’s successful, is it does a good job. Now, do we make mistakes? Yes. Is there room for improvement? I hope so. Are we dedicated to doing better and continuing to improve? Absolutely.”

Yet others don’t agree.

“There is something very horrible going on in this part of the state that doesn’t appear to be going on in other parts of Florida,” said Donna Cohen, director of the University of South Florida’s Institute on Aging, who reviewed the Times research. “When people have been committed two, three, four, up to eight times, at the age of 80 and 90, you have to begin to wonder about the abuse of humanity.”

Changes in the Baker Act are long overdue, said Martha Fenderman, who oversees mental health programs for the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services. Hospitals use loopholes to treat people “who could and should be treated in place, whether in nursing homes, retirement homes, or their own homes,” Fenderman said. “It has been very frustrating to see what we know is wrong but not have the legal foundation to do anything about it.”

The Baker Act

Sometimes people need a psychiatric hospital whether they want one or not. People with chronic schizophrenia, for example, sometimes stop taking the drugs that manage their illness. A week in the hospital gets them back on medication and back in control.

On the other hand, mental illness is no crime. The community can’t just lock up everyone who acts strange. In the early 1970s, Florida passed a commitment law designed to protect individual rights. It is called the Baker Act, after state Rep. Maxine Baker of Miami, who championed mental health reform.

Before the Baker Act, people could be committed into institutions for months, even if they weren’t dangerous. Court oversight was limited. Now people can be locked up only if they are dangerous to themselves or others, or if self-neglect poses a real threat. To keep them longer than 72 hours, hospitals must petition the court. People get lawyers to defend them and formal hearings before a judge.

This legal framework works well for aggressive street people, suicidal teenagers, depressed adults, and others whose treatment can help them function in society. But many seniors are a different story. Their ills can’t be cured. And an attentive $80-a-day nursing home often can handle their problems better than a $400- a-day hospital.

Nevertheless, economic incentives help drive the Baker Act toward the elderly market. For starters, Pinellas County has 372 beds in private psychiatric hospitals that can treat people committed under the Baker Act, far more beds than any other urban county in the state. Palm Beach County has only 55 such beds— even though Pinellas and Palm Beach have roughly equal populations and about the same number of elderly.

Now compare the number of times doctors and psychiatric facilities in the two counties committed people into treatment in 1994. Palm Beach doctors and hospitals forced 410 people into treatment, about one-third of them elderly. Pinellas doctors and hospitals committed 1,573 people, two-thirds of them elderly, court records indicate.

“With so much competition among free-standing psychiatric hospitals to fill beds, there would certainly be an incentive to seek out bigger and bigger market shares,” said Lenderman.

Impartial Hearing

Almost all commitments under the Baker Act start with a 72-hour examination. For hospitals to detain a person longer, the courts must approve. Based on evidence, a judge can commit people up to six months.

This is the keystone of the Baker Act — the right to an impartial hearing. But hospitals and doctors hold sway. Testifying for the hospital is a doctor presumed to be the expert. Both doctor and hospital may have a financial stake in detaining the patient.

Psychiatrist Ronald L. Knaus, for example, evaluated most involuntary patients and testified at most of the hearings at the Manors in 1993 and 1994. He also worked full-time at the Manors and was an investor in the hospital.

Knaus said his investment was small, and financial considerations never influenced his decisions on care. He said he would have made a lot more money working in private practice. “I think I’m a typical mental health person that has this need within myself to rescue people or to help people.”

Speaking for the patient in the hearing is a public defender, often fresh out of law school, with loads of cases and little time to prepare. The law allows for private attorneys, but few patients hire them.

Each patient also gets two representatives — family members, friends, or others — who can speak on their behalf. But some patients have no family close by; others have representatives who are eager to help but don’t get the chance.

Bill Hamilton was designated to represent his 79-year-old tenant and friend, Mildred Sprauer, but hospital staff refused to let Hamilton or his wife Helen visit, saying it would upset Sprauer too much, Hamilton said. And their notice from the court arrived after the hearing. “We never got to speak out for Mildred at all,” Helen Hamilton said.

Some elderly patients are in no condition to speak for themselves. Hearings take a week or so to set up. By then, heavy-duty drugs sometimes sap whatever capabilities the patient may have demonstrated.

Deborah Diesing remembers the day her 88-year-old great aunt, Gertrude Sedlak, was wheeled into a hearing at Horizon Hospital. When Diesing had visited the night before, her aunt was alert, well-groomed, and pleasant. But that night Sedlak’s doctor changed her medication to combat agitation, records show. In the morning, orderlies wheeled a pathetic, zonked-out woman into the hearing room, Diesing said.

“They brought her down wearing clothes that were not her own. Her hair was totally messed up. . . . This woman who normally smiles all the time looked up and smiled and had no teeth. She looked like a refugee.”

Lee Ghezzi, Horizon’s nursing director, said the change in Sedlak’s medication had nothing to do with her hearing. He said the previous medication was ineffective. At the hearing, a doctor testified that Sedlak was confused and disoriented. The hearing master let Horizon keep her 21 more days.

Diesing felt doubly tricked. She had brought her aunt to Horizon because Sedlak was having trouble sleeping at a Seminole retirement home, she said. A Horizon marketer persuaded Diesing that a two-week hospital stay could stabilize her aunt and get her sleeping, Diesing said. She had no idea the hospital would turn around and petition the court to detain Sedlak against her will.

Sedlak now lives in a different nursing home and is sleeping better. Why? Not because of mind-altering drugs or institutionalization, says her niece. Her caretakers simply keep her a lot more active during the day.

Other Options

As interpreted in Pinellas County, the Baker Act usually rests on two expensive assumptions. When old people get confused and agitated, they must be medicated. And the safest place to do that is the hospital. That’s the mantra that doctors and hospitals offer the courts, time and again.

Many geriatric experts disagree with both assumptions. Nursing homes with properly trained staffs often can manage problems for less money and with much less trauma. “The medications are available, the adjustments aren’t complex,” said Dr. Bruce Robinson, chief of geriatric medicine at the University of South Florida. “Much movement to the hospital doesn’t have a lot of social benefit.”

Officials at some nursing homes agree. In 1993 and 1994, several nursing homes went a year or more without sending a resident off for psychiatric treatment, court records show, while other homes sent more than a dozen.

Creative caregiving often can manage an agitated resident, said John Carnes, a Bayfront Medical Center psychologist who consults at St. Petersburg’s Menorah Manor. One confused woman, for example, thought she was the office manager and bossed the other residents around. Tensions ran high until the staff set up a desk in an unused alcove. “We put a telephone and typewriter in and said, ‘This is your office,’” said Carnes. That calmed the woman and kept her busy.

Carol Woodworth saw both approaches to caregiving.

Over 11 months, her 82-year-old mother, Edith Nehring, was forced into a mental hospital four times and lived in five nursing homes, her health steadily deteriorating.

She landed in Tyrone Medical Inn, a home that hasn’t committed anyone for at least two years, officials there said.

“She loved it,” Woodworth said. “She was so close to the staff, knew everybody. The cook knew my mom wanted extra gravy on her food. It was like a family.”

Excerpted by Marc Miller

It Could Happen to Anybody

By Carol A. Marbin and Stephen Nohlgren

It was a routine report, like hundreds of state social workers receive every month: Helen Tooker was not eating. She wasn’t caring for herself.

But Cecil Odom, who investigated the allegation last year, found Tooker to be anything but ordinary. Then 87, she had been an artist for half a century and raised five children alone during the Depression. For two hours, Odom was captivated by Tooker’s stories of famous people she’d known and the many places her paintings hang.

As a young widow, Helen Tooker had supported five children by painting advertisements on the back of window shades and stage curtains. In her 70s, she was the official artist for the H.M.S. Bounty exhibit in St. Petersburg.

“She told me how proud she was of her art and her history. She went on and on about where her paintings are, how far they’ve been, who she’s been in the company of,” Odom said.

Sure, she could use a little help to stay at home, like many other elderly. So the social workers made plans to bring in household help.

Then the Baker Act intervened. Tooker’s son, who lived on Florida’s east coast, petitioned the court to commit her to Horizon Hospital for an evaluation. She was depressed and had “stated that she no longer wants to live,” wrote the son, who declined to comment for this story.

His say-so was all it took for a judge to order her into the hospital for three days. There, misconception and innuendo kept her locked up. When powerful mind-altering drugs made Tooker too dizzy to walk, she wouldn’t get out of her wheelchair. The doctor called that a sign of depression.

When Tooker refused to cooperate, she was branded irritable, hostile, and suspicious, court records show. “She wants to know why I am asking these questions,” psychiatrist Debra Barnett later testified.

When Tooker said she was an accomplished artist and had illustrious friends, she was disparaged as “grandiose” and her stories deemed “questionable.”

Somebody mentioned that Tooker kept loaded guns. She testified that her son had dropped one off at least 20 years earlier and she didn’t know if it was loaded.

After 15 days, Circuit Judge Thomas E. Penick Jr. held a hearing and freed Tooker, calling her commitment a travesty of justice.

“That was a landmark case that just mortified me,” Penick said. “Helen Tooker could be Miss Anybody USA. That could happen to you, to my mother-in-law or anybody else.”

“That was a nightmare,” Tooker recalls. “It took me two weeks to get out of that god damn hole.” Group therapy, which included music, bingo, and reminiscing, “bored me to tears,” she said. “The average child would turn up its nose at it.”

Today, Tooker lives at home with her French poodle, Sissy. Social workers send a cleaning person around three times a week. Her experience with Horizon was draining, she said, but “I made it to 88, and I’ll make it a little longer. It’s always been a fight for my life.”