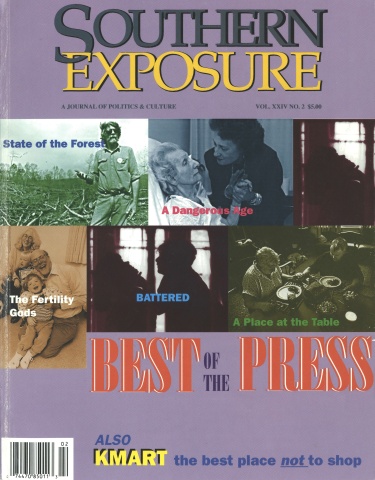

Alice and Carol: A Place at the Table

This article first appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 2, "Best of the Press." Find more from that issue here.

To profile an ordinary lesbian couple, reporter Elizabeth Simpson and photographer Beth Bergman accompanied Alice Taylor and Carol Bayma for four months — at church, picnics, and evenings at home.

As soon as some people saw the word “lesbian” in the headline, they picked up the phone to complain. But in the following days and weeks, the newspaper and the couple received reams of positive responses:

▲ Gay couples said Alice and Carol helped the world see that gays and lesbians were ordinary people trying to live ordinary lives.

▲ A gay teenager said she had been suicidal in the past but felt more courageous after reading about Alice and Carol.

▲ Straight people thanked the paper for a vision of a couple who were peaceably working to be part of their community.

▲ People thanked the couple for coming out in one of the most public ways possible and the paper for allowing gays “a place at the table.”

VIRGINIA BEACH, Va. — Some months ago, Alice Taylor was asked to tell the story of her coming out as a lesbian. For a newspaper article.

She wasn’t sure what to do, so she wrote out a list of why she should do the interview, and another of why she shouldn’t.

The “should” column was empty.

The “shouldn’t” one was full: The violence she and her partner might suffer; the hurt feelings it could cause in her church; the impact on the small ministry she runs for the homeless; the feelings and privacy of her children.

She asked her long-time partner what she thought. Carol Bayma quoted Esther 4:14 in which Mordecai poses a question to his cousin, Esther, who must decide between remaining silent or speaking up to save other Jews from persecution: “Who knows whether you have come to the kingdom for such a time as this?”

For Alice and Carol “such a time as this” is now.

This is the time to tell a story about one quiet couple in one church in one average neighborhood. Two women — both in their 50s — who have spent decades opening the door of their sexuality, to themselves, their children, their relatives, their friends, their church, their community. Who have asserted their identities quietly — not through lawsuits or hunger fasts or marches.

And who have been shunned and embraced as a result.

They have learned there’s a difference between people speculating they are gay and knowing definitely. “It was OK when you were just you,” one friend confided to Carol. “Why did you have to go and make it official?”

In their own small circles of church and family, they have put a face on the issue of homosexuality. They have challenged stereotypes with their long-lasting relationship. Their gray-headed normalness. Their quiet Christian ways.

And they are doing the one thing they vowed to do when they began their relationship 23 years ago: they are growing old together.

Alice, a soft-faced woman with a warm smile and feathery gray hair, is late coming home tonight from her job with St. Columba Ministries, an ecumenical group that helps the homeless. Carol has turned on a light outside the couple’s Virginia Beach house.

When Alice walks in, she goes over to Carol, grasps her hand, and smiles. Blue eyes meet blue eyes: crinkled laugh lines appear on the two faces. The two say nothing, but speak the unspoken language of couples.

Two decades ago, that same look gave Carol her first clue that Alice liked her in a way very different from the usual friend. “There came a time when I realized she was happy to see me,” says Carol, a smooth-cheeked woman with short-cropped, gray hair. “When her face lit up.”

Snapshots of Alice and Carol’s children and grandchildren clutter the piano top. As Bernie, their dog, flops down on the floor, the two women piece together the mental snapshots of coming out.

Carol thinks back to when she was 9 or 10 years old. She sees herself pedaling down a dusty road in the Michigan town where she grew up. She was with friends. One by one, the others dropped off the trail. They didn’t like the long bike rides. Or the sitting for hours next to a lake, gazing at the thin reeds and roosting birds. Sitting, thinking, daydreaming.

Carol didn’t mind leaving the others behind. She was an intense young girl who liked to spend time alone. Even as a young girl, she sensed something was different about her. She dreamt the typical girlhood daydreams — where she was the heroine, saving someone — but that someone was always a girl, never a boy.

One place she was well-rooted was the church. The preacher at her Presbyterian church was progressive for the 1950s, inviting African-American children to church socials and sending the segregated, prejudiced congregation into a tailspin. Even though he knew the congregation didn’t agree with him on various social issues, he stood his ground.

That tolerance later helped Carol square her sexuality with her religion. While fellow Christians might use the Bible to attack her, she believed that God loved her. “In church I was encouraged and treated like someone good,” says Carol, now 52, and a civilian employee of the Navy. “As long as I was connected to the church, I never felt alienated from God.”

After high school, Carol married a Navy man and moved to Virginia Beach, but all along she felt like she was pretending. She wanted children, to pour herself into motherhood. Jennifer was born five years into the marriage and Ben a few years later. For years the duties of being a parent distracted her from a fading relationship with her husband.

Enter Alice.

At a book-club meeting, Alice noticed one woman in the circle of members. The woman hadn’t read the book, but she was still vocal about her opinions. Then she fell asleep in the middle of the meeting.

Alice took an instant dislike to her. She was obnoxious. Egotistical. A loudmouth.

The woman was Carol.

Still, a friend thought Alice and Carol had a lot in common. And true to the friend’s intuition, Alice connected with Carol. They were both in unhappy marriages, both trying to raise children in households that didn’t feel right.

First the two women talked about books. Then, religion.

Alice had never had a strong connection to the church, but Carol talked her into going to services at the Presbyterian church she belonged to. Then Bible study and Sunday school. More discussions. More church activities. Alice joined the church. And Sunday school.

The two women discovered themselves as much as each other. They gardened together, took family trips together, even vacationed together. They baby-sat each other’s children. Alice helped Carol get a job during a period when Carol couldn’t seem to stick with anything. She helped her line up job interviews, scolded Carol when she ran late for work, told her she needed to take more responsibility.

And Carol helped Alice out, not as a lesbian, but as a person. When they first met, Alice was painfully inhibited. She wouldn’t let other people touch her. If someone sat next to her, she moved. She wouldn’t talk unless spoken to first. She rarely laughed.

Carol got Alice to loosen up, to talk with other people, to hug and touch. To be human.

Carol asked Alice to sing in the church choir, which Carol directed.

“I can’t,” Alice said.

“Yes, you can,” Carol answered. And Alice joined.

Then, Carol asked her to sing a duet.

“No, I can’t do that.”

“Yes, you can.” And Alice did.

“I can’t say there was love there then, because I didn’t know what love was,” Alice says. “In my whole life I didn’t know what it was. But Carol touched me somewhere in my spirit and personhood. She called out to me things I didn’t know I had. She softened me. I was a brittle, severe person. She taught me to laugh.”

One thing they both knew in those early days of their friendship was they weren’t finding love in their marriages. Carol knew why sooner than Alice.

One day, six months after meeting, they were sitting at the kitchen table at Alice’s house, having one of their usual three-hour discussions. By this time, Carol had acknowledged to herself she was gay. She needed to tell Alice. Carol was beginning to be attracted to her, and she had to find out how Alice felt about homosexuals. If Alice had a problem with gays, Carol would have to leave.

Worried about how Alice would react, Carol couldn’t get the words from her throat to her mouth. So she picked up a matchbook cover and wrote down a single sentence. “I’m a homosexual,” it said.

Alice read it. “Oh,” she said in a nonchalant manner. “Okay.”

Alice filed it away in her head, but it didn’t matter too much to her. She had met gay people before, so she felt no surprise or condemnation.

Carol was instantly relieved. By this time, her eight-year marriage had broken up, as had Alice’s 13-year one. Carol began courting Alice in the weeks after. Flowers. Little gifts. Phone calls. She asked Alice to go for a walk on the beach, what she considered a first date, but Alice broke her arm playing softball the day before.

For three nights after that, Carol stayed by Alice’s side in the hospital, talking with her, making sure her children were OK. When Alice went home from the hospital, Carol stayed with her to cook and help out.

Alice couldn’t wait until Carol showed up. It was the first time she had leaned on someone emotionally for help. “I didn’t know when I began to fall in love,” Alice says. “I know I was terrified. I kept thinking, ‘This is wrong, this is different, this is not the way things are supposed to be.’”

Ambivalence was the rule for years. Pushing forward and pulling back, a mix of friendship and love.

Carol wanted to move in together, Alice didn’t. Carol wanted to tell the pastor of their church, St. Columba Presbyterian in Norfolk, about their relationship; Alice said it was too soon. Carol made sure her children knew she was a lesbian; Alice held back telling her three children.

Then they met a couple at church who would play an important role in their lives.

Jim and Linda Davenport, along with other church members, became a second family to the couple. When Jim was in the hospital during the last few days of his life, Carol and Alice helped Linda care for him around the clock. They split shifts, one spending the day with him, the other the night.

Jim died one morning in 1979. Alice drove Linda home while Carol took care of some of the funeral arrangements. “I thought Jim and I were going to grow old together,” Linda told Alice on the drive home.

The words “grow old together” struck Alice so strongly she heard nothing else the entire ride home. The sound of the words filled her head, her whole consciousness. “Grow old together.” She considered the message Jim’s parting gift to her.

Alice went home and called Carol. “You have to put your house up for sale, and I’m going to do the same. We are going to grow old together. I’m not going to miss what Linda and Jim missed.”

After that, it would be a gradual coming out, as each saw fit, as the situation presented itself. Children, parents, friends, family. Some people were never told. “I am careful about who I make friends with or who I come out to,” Alice says. “I come out when there’s a need. Their need or my need.”

Nowhere would coming out be quite so frustrating as in church.

St. Columba Presbyterian Church proved to be a good experience. The church, a small, intimate congregation, ministered to families in a nearby low-income housing development. Carol and Alice threw themselves into the church, teaching children, setting up a ministry for the homeless, mowing the grass, helping with fundraising.

One day the pastors posted a job for youth director. Alice wanted the job, but she felt she needed to tell the pastors she was a lesbian. She worried they’d disapprove of her working with children in a formal, paid position.

The husband-and-wife pastors — Caroline Leach and Nibs Stroupe — didn’t mind. They welcomed her coming out. In fact, they had been waiting for her to tell them. Alice got the job and later also served as an elder, a leader elected by the congregation to sit on the “session,” the organization that ran the affairs of the church. Carol also became an elder.

The comfort didn’t last long. The church folded six years after they joined because the housing development closed. The ministry for the homeless, which Alice still directs, continued under the name St. Columba Ministries, but Carol and Alice had to start looking for another church.

They chose Bayside Presbyterian Church in Virginia Beach, a medium-sized congregation where their children could be part of youth activities they’d missed out on at St. Columba, which focused on serving the poor.

Within a few years both Carol and Alice were once again deeply involved in the church. They helped raise funds for the homeless, led Bible study classes, sang in the choir. Alice served on the session for three years. Both did the things they did as elders at St. Columba, helping with baptisms and giving communion.

Still, they served “from the door of the closet,” as they put it. Although they didn’t tell people they were gay, they believed many people knew. They lived at the same address, shared the same telephone number, came to church functions together. They were treated as a couple.

Carol and Alice continued in this don’t-ask-don’t-tell mode until four years ago. Carol was sitting in Sunday school class. Fidgeting. Tired of the feeling she got when the subject of homosexuality came up in the class, which it had four weeks running. The sound of her own silence made her feel like a coward.

“If something comes up today, I am going to say something,” she vowed.

It did, and she did. “I can’t be quiet anymore,” she began, the words sticking in her throat. “You don’t know who I am. I’m a lesbian.”

The discussion went on without missing a beat. One elderly woman — who Carol thought was extremely conservative — reached over and gave her hand a squeeze.

It was a liberating feeling. She had admitted she was gay, and the world didn’t cave in. It felt good. Affirming. “They just listened to me, and we moved on with the lesson,” Carol remembers. “It was not a major thing.”

Carol sensed the congregation was hungry to learn more about the topic, and she asked the pastor to have a study on the subject of homosexuality and the church. A gay man who worked in an AIDS ministry came to speak, but congregation members who came to listen started interrogating him, attacking his homosexuality.

“But the Bible says . . .” they interrupted his speech.

“But God says . . .” when he began again.

“Right here in Scripture it says . . .” a third time.

They didn’t let him finish. He finally sat down, defeated.

Alice and Carol felt crushed. Alice approached one of the women in her Bible class afterwards. “What you did to that young man was unconscionable,” she said, a prickly heat rushing over her. “I am a lesbian, and what you did to hurt him hurt me.”

The exchange opened a floodgate of emotion. Homosexuals were no longer “out there” but among the congregation. Church meetings were held to discuss the issue. Accusations were leveled that a gay had “sneaked onto the session.” Anger was vented that Carol and Alice had taught Sunday school classes and served communion.

People called them an abomination; others reminded the critics that Alice and Carol were the same people they were the year before.

Some friendships ended. A very good friend of Alice’s turned the other way when she saw her or Carol walking down the church hallway. But others supported them. One young man confided in them he was gay and hadn’t had the courage to tell his parents.

In the months after that, Alice and Carol no longer were called to serve communion. They were told their names hadn’t come up in the rotation, but after more than a year went by, they asked what was going on. The session agreed to address the issue. In a letter hand-delivered to them in April, the elders told them they could no longer serve communion.

There would be other slights. Carol stood up in church one Sunday morning during announcements to let the congregation know about a Presbyterians for Gays and Lesbians meeting. Soon a petition was circulating asking that members not be allowed to use the words “lesbian and gay” during services or to post items on the bulletin board.

Now, four years after they came out at Bayside, Alice and Carol feel some frustration but regret nothing. “Many, many people have to be questioning the issues,” Alice says. “They have to say, ‘They are not the ones we see on CNN doing demonstrations. They aren’t child molesters. They don’t have multiple sex partners. They don’t do pornography.’”

She pauses and thinks back to her childhood and her attitude toward African Americans. “I was raised to be very prejudiced. Then, when I was older, I began to meet blacks who were smarter than me, better than me. And I thought, ‘Something is wrong with what Mom and Dad said.’

“To me, we are not an abomination. They [members of the church] have to see God in us. They have to be questioning what the drumbeat is saying.”

Carol and Alice feel now as though they check a part of themselves at the church door. Still they go, their twin heads a fixture in the front pew. Still they are friends with church members. Still they are involved.

“We feel there is purpose to our being vocal, a reason to it,” Carol says, explaining why they haven’t left Bayside. “There are people there who support us as individuals, who believe it’s important for us to be working on this issue in the church.”

One Saturday night in April, Carol and Alice sat around a table with eight other people eating curried rice. Their banter ranged from serious issues to funny stories that filled the room with peals of laughter.

The gathering, called The Fellowship of the Table, is the brainchild of Rebecca Kiser-Lowrance, the wife of Will Kiser-Lowrance, Bayside’s associate pastor. She’d seen all the people of the church who were looking for a place at the table but couldn’t find one. People who have been turned away, people who were hurting. People like Alice and Carol. This was a place for them to gather, ask questions, grow stronger in their faith.

As Will Kiser-Lowrance sipped coffee, he told a story about when his daughter was born with a condition in which her intestines had failed to develop. Alice and Carol would come over to take care of her so he and Rebecca could take a walk by themselves.

Emmy died when she was seven weeks old. Will could not forget Carol and Alice’s kindness. “To hear people at church call them an abomination makes me angry,” he said. “Before I met them, my way would have been to support gays privately but to be silent publicly because of my job. It took two lesbian women to make a man out of me.”

Will said one of the toughest things for some congregation members had been to square Alice and Carol’s good works, kind ways, and knowledge of the Scripture with their homosexuality. He said the church had stopped for a breath on the issue, but it would rise again. Before, homosexuals were an amorphous, anonymous group for many people; now they are Alice and Carol.

The church is not the only place Alice and Carol have challenged people’s beliefs.

They recall the different reactions they’ve gotten over the years to their coming out: Alice’s maid of honor broke off their friendship after Alice wrote to tell of her coming out. One of Alice’s sons says he’s “still having trouble with it” and won’t discuss the issue. Carol’s parents ignored Alice for years and refused to visit Alice and Carol’s home.

But others have accepted them. After her husband died, Carol’s mother became friends with Alice and showed off birthday cards signed by both women. Alice’s three-year-old grandchild Meredith calls Alice “Grandma” and Carol “Grandma Carol.” Tom House and others have sat by them in church even through times of controversy.

Frank Taylor, Alice’s older son, can understand the mixed reactions. He’s found himself on both sides.

He didn’t question his mother’s relationship with Carol until he was 25 years old and married. After a family gathering, his wife said, “You know, I think your mother and Carol are gay.”

“Mom? Nahh,” he responded.

He decided to ask her and went by her office at St. Columba Ministries.

He took the news hard. He felt betrayed by his mother for not telling him sooner and angry at Carol “for switching” his mom. He stopped visiting them.

Finally, he went to a counselor for help. She asked him to list the things he liked about his mother and the things he didn’t. He wrote that she was a compassionate person. She had concern for people’s feelings. She supported him. She was easy to talk to. She gave of herself.

On the “dislike” side was only one item: her sexual preference. “It’s not worth giving her up for that,” he thought.

Frank is now 34, an avid fisherman, a commercial painter. At a family cookout, he talked about his struggle in accepting his mother and her partner.

“I’m kind of proud of them now, proud of both of them really. I feel like they’re pioneering types. If my friends criticize gays, I say, ‘Hey, ease back. My mom’s gay.’”

Alice and Carol are in their living room for a final interview. They ponder the question of why they have opened their door to a reporter.

“Does there have to be an answer?” Alice asks, her brow furrowing. “Can I say, ‘I don’t know?’”

By now Alice is tired. Tired of the questions, tired of the intrusion. “I am tired of the issue itself,” she says wearily. “It’s so little of who I am. I’m a mother, a friend, a partner. I do ministry. I’m a homosexual. I’m a right-handed, blue-eyed old woman. To boil it down to my homosexuality is unkind.”

But Carol knows why they are coming out in such a public way. The reasons spill from her. Teenage gays who are committing suicide in frightening numbers. Stereotypes that don’t fit reality. The need for role models. The young people who have come up to them and thanked them for leading the way.

“The world is a gift to us,” Carol says. “And we can’t accept the gift and hide who we are. There’s no guarantee it will get better if there are not gay people willing to be known.”

Even though she is quiet, Alice knows the answer, too. That’s why she is here telling this story.

For such a time as this.

Tags

Elizabeth Simpson

The Virginian-Pilot, Norfolk (1996)