Virginia for Sale

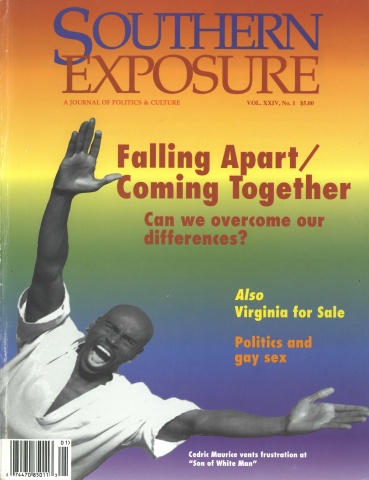

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

When George Allen ran for governor of Virginia three years ago, he emerged as one of the earliest republican champions of “regulatory reform.” The state, he said, was suffering “under the heavy, grimy boot of excessive taxation and regulation.” Before Newt Gingrich conceived the contract with America, Allen promised to transform state government by slashing bureaucracy and weeding out rules not essential to safeguard public health and welfare.

So when Allen created a new board last year to investigate complaints against car dealers, it looked like he was making good on his campaign promises. The state Motor Vehicle Dealers Board will operate on an annual budget of $1 million — less than half what the state used to spend monitoring car dealers, and all of it covered by fees from the industry.

A closer look, however, reveals that the new board may be taking consumers for a ride. The state staff responsible for licensing 3,600 dealers and keeping an eye on nearly 700,000 car sales each year has been slashed from 40 to 25, including six part-time employees. And the governor has handed over control of that staff to car dealers themselves — including many who were among the biggest contributors to his 1993 election campaign.

When the board meets in Richmond, 16 of the 19 members seated around the conference table represent the car industry. At least eight are car dealers who gave money to Allen through their companies or out of their own pockets.

Take one typical meeting last fall. At one bend of the table sat Arthur Casey, a Hampton Roads car dealer who gave Allen $4,000. Next to him sat Frank Cowles, a Woodbridge car dealer and long-time Allen supporter who gave the governor $3,450. A few chairs over sat Tom Barton, a Virginia Beach Ford dealer and vice chair of the board. He gave $2,550. Missing that day was board member Richard Sharp. He is chief executive of Circuit City Stores, which has begun a highly touted chain of CarMax used-car “superstores.” Circuit City and its executives gave Allen $57,500.

In all, the governor reaped $71,800 through eight companies that now have a seat at the table when the Motor Vehicle Dealer Board meets.

Allen supporters say the creation of the car-dealer board shows the governor is taking power from bureaucrats and letting the private sector breathe businesslike efficiency into the regulatory process. “I think he was looking for people who had the experience and had reputations they’ve built over the years,” says board member Richard Kern, a Winchester car dealer who gave Allen $2,300. “People that certainly weren’t going to be ‘yes men’— and who’d do what’s best for the state.”

But the car-dealer board is part of a broad effort underway in Virginia to let business interests and campaign contributors decide what’s best for the state. In effect, Allen has moved to lock average citizens out of the governing process, stacking regulatory boards with representatives of the very industries they are supposed to regulate. His administration has weakened state agencies designed to protect consumers and the environment, making it easier for shady businesses and polluters to operate.

What is happening in Virginia offers a preview of what other states can expect if the GOP continues expanding its control of the Southern legislatures — and if Republicans in Congress succeed in giving more regulatory control to the states. “Virginia is being sold to the highest bidder,” says Gary Kendall, a Charlottesville lawyer who works with labor, consumer, and environmental groups. “We’re telling businesses, ‘Come to Virginia; we’ll let you have your way.’ The theory is if we have cheap taxes, cheap labor, and no government interference, employers will come. We’re becoming the Mexico of the U.S.”

Icing the Hot Line

When Allen ran for governor, he said Virginians were sick of bureaucrats telling them what to do. He promised to “put the people back in charge” and blasted his Democratic opponent, Mary Sue Terry, for “shaking down special interests who want to curry favor” with state government.

“Virginians won’t be bought,” he told a group of Ross Perot supporters in Roanoke. “And Virginia government is not for sale.”

Now, Allen is running state agencies that oversee the same industries that gave generously to his campaign and inauguration. He received $164,000 from coal companies and other mining firms, $171,000 from oil companies and other energy interests, and $311,000 from manufacturers.

In all, at least $1.6 million of the $3.9 million that Allen accepted in campaign contributions of $500 or more came from business interests. What’s more, 85 percent of the $429,000 the governor collected for his inauguration came from businesses or corporate law firms.

From a business perspective, the money was well spent. As soon as Allen was sworn in, his first act as governor was to name a task force to develop ideas to “streamline” state agencies. The goal of his administration, he said, was to curb bureaucracy and create “a probusiness, pro-economic growth environment.”

In practical terms, that has meant easing the enforcement of laws aimed at protecting people’s pocketbooks. The administration has cut the staff of the state consumer affairs program by nearly half and shut down a toll-free hot line for consumer complaints. Consumer advocates say the cuts leave citizens more vulnerable to unscrupulous telemarketers, shady home contractors, and other scam artists.

Allen has also pushed for “self-regulatory” boards that put car dealers and other business people in charge of policing their own businesses. Car dealers insist that they will protect consumers. “The board wants to see that the customer is treated fairly,” says Art Heberer, a board member who runs an auto-parts recycling business in Salem. “The incentive to do this is to make sure that your customer is happy so they’ll come back and buy another car from you later.” But consumer advocates say the board will make it even harder to help individuals who have been wronged and to end patterns of misconduct. “The structure of this — turning it over to the industry — isn’t adequate to protect the public,” says Jean Ann Fox of the Virginia Citizens Consumer Council.

Fox points to a dispute over whether dealers should disclose their processing fees — which typically range from $99 to $200 — in a car’s advertised price. The Consumer Council says yes. Dealers say no. An informal survey conducted by the Richmond Times-Dispatch showed that some members of the car-dealer board charge among the highest processing fees in the state.

Although there is one consumer on the board — added by the General Assembly after Governor Allen proposed membership for dealers only — consumer advocates predict the board will operate more as a trade group than as a watchdog agency. “Business people inherently have business as their first order of business,” says Julie Lapham, director of Common Cause Virginia, a Richmond-based advocacy group. “The citizen gets relegated to the back burner.”

Dirty Money

In addition to weakening protection for consumers, Allen has hobbled state agencies responsible for safeguarding air, soil, lakes and rivers, parks, and animals. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has lost 20 percent of its staff since the governor took office, and former and current staffers say the agency has become too cozy with the businesses it’s supposed to watchdog. Peter Kostmayer, a former regional director of the federal Environmental Protection Agency, calls Allen “the best friend Virginia polluters ever had.”

Virginia has never been known for being particularly tough on polluters. In 1988, for example, newspapers lambasted the administration of Democratic Governor Gerald Baliles for being too lax on the pesticide control industry. But environmentalists say Governor Allen is trying to gut even the modest protections the state has provided to ensure clean air, land, and water. “Things have gone from bad to terrible,” says Gary Kendall, the Charlottesville lawyer.

Environmentalists charge that campaign contributions the governor accepted from big polluters appear to influence his lax stance on protecting natural resources. During his 1993 campaign, Allen took $10,000 from Smithfield Foods, a meat-packing company that has since run afoul of environmental laws. According to DEQ records, the Suffolk-based company violated state water pollution regulations at least 23 times between May 1994 and July 1995. In addition, federal officials are investigating the disappearance of thousands of company environmental records.

Smithfield Foods seems satisfied with the treatment it has received from the Allen administration. Last year the meat packer contributed $125,000 to the Campaign for Honest Change, a political action committee the governor set up to finance his bid for a Republican majority in the General Assembly.

The governor has also appointed big campaign contributors to top environmental positions. Peter Schmidt and his firm, Allied Concrete Company, contributed $27,500 to Allen’s campaign. In March 1994, an Allied subsidiary was involved in an environmental fiasco when it provided 200,000 tons of “fly ash,” a byproduct of coal-fired power plants, to help transform an old city dump in Norfolk into a park. The ash was washed away by torrential rains, creating a gray sludge that oozed knee-deep into the surrounding neighborhood and clogged two acres of federally protected wetlands. Three months later, Schmidt was named director of the Department of Environmental Quality. Since then, the agency has approved new regulations allowing even greater use of fly ash — a move that directly benefits his former company.

Allen paints critics of his “regulatory reform” efforts as opponents of economic growth. “I do think that regulations have to be reasonable and take into account the impact not only on woodpeckers, but also the impact on people,” he says. Yet the record shows that the governor has moved to weaken government oversight and responsibility for the environment:

▼ Without public notice, the DEQ changed a rule that limited shipyard discharges of TBT, a highly toxic pesticide used in boat paint to keep the hulls free of barnacles. Joe Maroon, Virginia director for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, says the agency “quietly pulled” those limits in a permit renewal for Norfolk Shipbuilding and Drydock Corporation. The state restored the limits only after the federal Environmental Protection Agency and hundreds of citizens voiced objections.

▼ The DEQ stopped cleanup at about 2,000 sites where leaking underground storage tanks had polluted the soil or ground water. Under a new procedure, the agency only enforces cleanup at sites that pose an “immediate risk.” The move saves tank owners millions of dollars in cleanup costs, but the pollution at closed sites could come back to haunt future or nearby property owners.

▼ State officials are exploring ways to contract with private vendors to provide services such as camping, restaurants, and horseback riding at state parks, running fish hatcheries, and advising farmers on erosion and runoff. Handing over government services to industry, critics say, would shift the emphasis from protecting people to generating profits.

▼ The DEQ proposed a change in regulations that would give the agency more discretion over whether to require water polluters to monitor for toxic substances. Critics say the change could mean some companies would get preferential treatment.

▼ The DEQ delayed designation of five western Virginia streams as “pristine” out of concern it would stifle economic growth in the communities where they’re located. The stream classification, part of the federal Clean Water Act, would mean that no more pollution could be discharged into the streams.

▼ The administration pushed for an “environmental audit” bill that grants immunity from civil liability to businesses that report environmental violations to the government. The bill passed into law last year — despite objections that it enables polluters to hide problems by making the information they give the government legally privileged.

Secrecy and Fear

Business has applauded efforts to “streamline” regulations. The administration is “moving ahead at a very acceptable pace,” says Sandra Bowen, a senior vice president with the state Chamber of Commerce. “Generally, the regulated community is happy with the way it is working so far.”

By contrast, citizens concerned about the environment have been locked out of the process. “It’s to the point I can’t even get a letter answered,” says Ed Clark, director of the Wildlife Center of Virginia.

Last year Peter Schmidt, director of the DEQ, convened three panels to streamline waste, water, and air permits. The panelists included agency staff, consultants, lawyers, and representatives of industry — but no environmental advocates. In a memo, Schmidt indicated the panel recommendations would remain internal policy and not be subject to public comments and hearings.

The public has been further shut out of the process by administrative secrecy. Officials have used the “governor’s working papers” exemption of the state Freedom of Information Act to keep many documents confidential — including environmental reports, a DEQ review of 25 regulations, and an “exercise” in which the agency listed programs that could be privatized or eliminated.

Citizens aren’t the only ones feeling excluded. Many DEQ employees believe clean air and water are taking a back seat to business needs. A survey of agency employees by legislative auditors found that 67 percent say their morale is fair or poor. Fifty-seven percent say their jobs would be at risk if they made a decision that was legal but upset industry.

David Sligh worked in the Roanoke office of the DEQ for 10 years writing water discharge permits before Allen appointees began applying top-down political pressure. Sligh said he was expected to overlook legal and technical problems in order to issue permits in a timely, friendly manner. “That makes me mad — as a taxpayer and a career government employee,” Sligh said. He quit the agency last year to serve as state coordinator of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, a national group.

Others have left as well. A combination of buyouts, layoffs and resignations has left DEQ with about 640 employees, down 20 percent from 1993, and far below the 1,000 positions authorized by the General Assembly when it created the agency.

At least one employee was fired. Don Shepherd had worked 15 years heading the Roanoke regional air office. He was regarded both inside and outside government as a middle-of-the-roader, someone who worked well with industry and who took the protection of Virginia’s air quality and public concerns seriously. When Shepherd was fired for revealing an internal disagreement over an air permit for a Radford industry, staffers throughout the agency were stunned — and took the incident as a warning.

“They’re scared to death to talk to me,” says state Senator Joe Gartlan, a Democrat from Fairfax County. “Morale is a disaster. Workloads are impossible. They simply can’t perform.”

Becky Norton Dunlop, secretary of natural resources under Allen and a former personnel adviser for Ronald Reagan, dismisses staff problems as a natural consequence of agency cuts. “It is tough on the employees,” she says, “but it’s not causing a lot of people to not do their jobs.”

Out of Step

Allen came into office with high popularity ratings, but public approval has dropped as his hard-right agenda has drawn more scrutiny. He made last fall’s mid-term elections a referendum on his governorship, funneling money from Smithfield Foods and other special interests to local GOP candidates and blanketing the state with TV ads featuring himself. But his bid to win control of the General Assembly failed.

His cuts in education and social services were the key issues, but there were also clear signs he was out of step with citizens on consumer and environmental issues. One poll conducted last fall asked voters which of three issues was most important: 61 percent picked “strict enforcement of current clean air and water rules”; 24 percent picked “limits on real estate development”; 15 percent picked “cutting regulation to help business.”

But the governor continues to cut state regulations — and to appoint some of his biggest campaign contributors to oversee the job. His agenda calls for giving industry more say, often at the expense of consumers. In the case of the car-dealer board, for example, Allen turned to a trade group rather than average car buyers for advice on appointments.

“Every one of these people who I appointed were recommended by the Virginia Automobile Dealers Association,” he says. “It’s not as if I just picked people out of the air.”

The industry group, which represents franchise dealers, gave Allen $23,600.

Many of those in business consider it natural for the state to turn to them to regulate their own industries. Frank Cowles, a northern Virginia car dealer whom Allen appointed to the Motor Vehicle Dealers Board, has been friends with the governor since they met at a GOP dinner a few years ago. Cowles says he “worked like hell” to get Allen elected to Congress and then worked again to get him into the Governor’s Mansion. Cowles, a lawyer who runs a hardware store and serves on the board of a bank, says he doesn’t understand why anyone would fuss about a world-tested businessman being put on the car-dealer board.

“What the hell are you going to do? Appoint somebody who’s a hillbilly who doesn’t know anything about this business?” he says. “Where is the problem in appointing qualified people?”

Local Control?

A rural mountain county can’t stop a corporation from burning them.

Rocky Gap, Va. — In between Hogback and Rich mountains, just a few miles from the West Virginia border, lies a quiet valley named after Wolf Creek. Not much happens here. Melinda Belcher’s cows sometimes get loose. The creek floods now and then. Even the traffic on the interstate that runs the length of the valley becomes a gentle hum in the distance. Residents hardly hear it anymore. Leverett and Peggy Trump retired here six years ago, Peggy being a native of Bland County. They picked a pretty spot, with a small field, some woods, and a stunning view of Hogback Mountain. About the same time, a company called CaseLin Systems Inc. was choosing a site three miles up the valley for a medical waste incinerator that could net it millions of dollars. Since then, the Trumps have seen their peaceful retirement turned into a part-time fight against the garbage burner. “It’s the worst possible place for it,” Leverett says. At 3,000 feet, and surrounded by ridges, the valley is prone to thermal inversions that trap fog and smoke from distant forest fires. The same thing would happen to air pollution from the incinerator, says Trump. “It just gets in there and stays for days.” Melinda Belcher, who lives near the Trumps, would be the closest dairy farmer to the incinerator. She worries that chemicals would drift down on the 150 acres where her cows graze and contaminate their milk. “It scared me because this is my livelihood,” she says. Dairy farmers, who must test their milk every time it’s picked up, are watched more closely than the incinerator would be. “That’s what got me,” Belcher says. “They’re going to check these boys once a year. And this is really gross, but you think about what they’re going to be burning. There is going to be a smell, and it is going to drive people away.” In December, the state Air Pollution Control Board approved a permit for CaseLin to burn 40 tons of hospital gowns, syringes, body parts, bloodied sheets, and other infectious waste every day, most of it from out of state. Most residents of Bland County don’t want it. They traveled to Richmond, testified before legislators, signed petitions, written letters — done all they can, in other words, to heed Governor George Allen’s call for Virginians to take an active role in government decisions. At a Republican fundraiser in Roanoke, Allen reemphasized that “local control” works best. “That’s just a fundamental belief — that we can trust people locally.” Yet opponents of the incinerator say the governor doesn’t seem to trust the people of Bland County. In keeping with the administration’s focus on economic growth and job creation, they say, the state recently loosened rules to allow the incinerator. When CaseLin first proposed the project, they observe, the county had little power to bar the burner. Opponents looked to Richmond, but the state had no specific standards for medical waste incinerators. With four other applications pending for similar burners across the state, the General Assembly imposed a moratorium on permits until rules were developed. The Department of Environmental Quality formed an ad hoc group, with industry, technical, environmental, and citizen representatives, which came up with standards in 1993. The Bland County opponents supported them as strict enough, and were told by DEQ at the time that the CaseLin permit would not pass muster under the rules. But a law enacted in 1993 delayed adoption of the rules, giving Governor Allen a chance to influence the process. The administration relaxed emission standards for particle dust, carbon monoxide, and other pollutants, as well as requirements for operator training and incinerator design and management. Opponents of the incinerator were outraged. “I want us to be a pro-business state, but not to the point where we jeopardize the health and welfare of our citizens,” says state Senator Jack Reasor, a Democrat from Bluefield. He says two members of the Air Pollution Control Board appointed by the governor tipped the scales to change medical waste incinerator regulations to favor industry. Administration officials insist the new regulations are based on “sound science” and will protect the environment and public health. “I understand that some of these issues are very emotional,” says Secretary of Natural Resources Becky Norton Dunlop. “I just think that, frankly, sometimes emotion carries the day on environmental policy and sound science gets, frankly, thrown out the window because it is more exciting to focus on controversy than the scientific evidence.” Now, county officials and citizens are facing another battle — whether they have standing to challenge the air permit in court. State law requires they must prove “immediate, financial and substantial” harm in order to have their day in court. Environmentalists say that test is too severe, but Allen staunchly defends it. “I was raised to believe the government would take care of us,” says Belcher. “I hate to say it, but I’ve lost faith.” Molly Thompson, a longtime Republican and vice chair of the county board of Supervisors, is behind Allen on most issues, but parts company on environmental policies — and especially on the incinerator. “I really wonder if he knows what it would do,” she says. “Should this come to Bland County, then I think all of Virginia needs to be aware of what is permitted. If we get one, you can get one, too.” — Cathryn McCue

Tags

Michael Hudson

Mike Hudson is co-author of Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty (Common Courage Press), and is a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1998)

Mike Hudson, co-editor of the award-winning Southern Exposure special issue, “Poverty, Inc.,” is editor of a new book, Merchants of Misery: How Corporate America Profits from Poverty, published this spring by Common Courage Press (Box 702, Monroe, ME 04951; 800-497-3207). (1996)

Cathryn McCue

Mike Hudson and Cathryn McCue are staff writers with The Roanoke Times. (1996)