Profiles in Cooperation

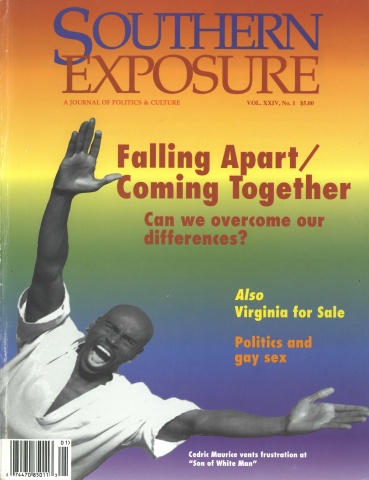

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

In a recent interview, Steve Rebmann, secretary of the Tennessee chapter of the Christian Coalition, said, “Being pro-life seems to be a common denominator for conservatives.”

Progressive grassroots organizations would be hard-pressed to name one issue around which they all can rally. Social justice may be a common goal, but it is not an inherently unified struggle. Groups may not immediately recognize that they have much in common. But many groups now recognize that to achieve real power, they must work with groups who might not look or speak the way they do or even share all of the same values.

The organizations profiled here found that the process of working with each other for change is hard, frustrating, and often slow to show results. But they have also found that the effectiveness of combined efforts is the reward for painful self-examination.

Lake City, Tennessee and Jackson, Tennessee

Save Our Cumberland Mountains and JONAH

East Meets West and Startles Legislature

When Save Our Cumberland Mountains (SOCM) was founded 23 years ago to address issues of concern to the five east Tennessee counties (Anderson, Morgan, Scott, Campbell, and Claiborne), its founders did not intentionally create an all-white organization. But the people living in those counties were predominantly white, and membership reflected the demographics of the area.

Six years ago, that began to change. SOCM (pronounced sock-’em) is a member of the Southern Empowerment Project, a coalition which brings together grassroots organizations in Tennessee, Kentucky, and North Carolina for training. At a conference in 1989, SOCM representatives met the members of JONAH, an all-black organization based in west Tennessee. JONAH, founded in 1977, and named after the Biblical character, works on issues similar to SOCM’s: tax reform, health care, workers’ rights, and the environment. In SOCM’s case, environmental issues include the fight against strip mining and toxic runoff from coal mining operations.

Members of SOCM and JONAH met at the end of the conference and realized the two were really sister groups. “We were so stimulated by JONAH members and their work with the Southern Empowerment Project, we decided that we really should come together,” says Connie White, past president of SOCM. “We invited JONAH to a leadership retreat in the fall of 1990. We thought we had a lot to teach and learn from each other.”

At one of their early meetings, SOCM and JONAH members set out a map of Tennessee and colored JONAH’s western counties green and SOCM’s eastern counties blue. Looking at the green and blue map, the two groups realized how their combined efforts would increase the power of both groups. They asked themselves what it would be like if the two organizations could work together on issues that concerned both groups.

One of those issues was abuse of temporary workers. In 1991, JONAH and SOCM held joint lobbying days at the state capital in Nashville. Connie White says they shared a “zillion” conference calls trying to decide which legislators should be targeted and what pressure they could bring to bear on the issue. Howard White, a JONAH board member, says, “When we went to Nashville together, we scared a lot of politicians when they saw the white faces and the black faces banding together.”

Unfortunately, Connie White admits, the time was not right for championing the rights of temporary workers. “With those joint lobbying days, we did not accomplish much of anything, but it was a good experience for both organizations. It gave us just a hint of what it might be like if we had a really strong coalition where there were members of both organizations in east and west Tennessee that could begin to sway some votes.”

The next issue the two groups tackled was tax reform. Sales taxes bring in most of the state’s revenues, which means that lower-income people, who spend a larger proportion of their income on taxed goods, bear a disproportionate share of the state tax burden. Tax reform threatens Tennessee’s wealthy because proposed packages call for a reduction in sales tax and the institution of Tennessee’s first state income tax. JONAH’S challenge and influence forced SOCM to take a stand on the issue.

“Tax reform in Tennessee — it’s a very divisive issue,” Connie White says. “Some people in our organization were really afraid to take a stand, but JONAH pushed us on this. ‘Are you going to do it or not?’ they said. JONAH was absolutely right on.” Because of JONAH, SOCM did take an organizational position in support of tax reform that would include some sort of income tax. The groups are continuing to push for reform.

In addition to working on issues, SOCM and JONAH members, who meet every six months, have taken part in a “Dismantling Racism” workshop conducted by the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond of Louisiana.

“I think one thing that we learned is the way to dispel myths is to have real relationships,” Connie White says. “SOCM, as a primarily white, primarily rural, primarily working-class organization of east Tennesseans, struggles with the same kinds of stereotypes and misconceptions that other people do. It was really important for us to have formed the relationship with JONAH. I don’t think we could have sat in a room and intellectualized our way out of racial stereotypes.”

Howard White of JONAH agrees that racial understanding is one of the best things to come out of the cooperative venture. “A lot of SOCM members live where there are very few — to none — African-American people. They had ideas about black people. When they get to meet you, work with you for a few days, all that changes. They’ve found out that some of these stereotypes aren’t true.”

Another positive result of cooperation is the move toward diversification of both organizations’ memberships. Howard White has just been named as SOCM’s first black board member and JONAH is trying to find new ways to attract whites to the organization. Not long ago, JONAH members accompanied SOCM on a door-knocking campaign in an African-American community in Clymersville in east Tennessee’s Roane County.

“The experience of having JONAH come with us and show us good approaches, that went really well,” Connie White says. “But we did not organize successfully in that African-American community. What we’ve learned is we shouldn’t assume that people in an African-American community will flock to an issue that we’ve identified is important to us. If we’d done it right, we would have done organizing in the community and asked them what they were concerned about. Our mistakes were not due to JONAH but to our own lack of experience.”

Despite the lack of headway during the joint lobbying days on temporary workers’ rights and the poor response in Clymersville, SOCM and JONAH are optimistic about the future of their relationship. Both organizations see it is in their self-interest to work together across racial boundaries. In each of its training sessions, SOCM now works to help members appreciate diversity.

“When you listen to what people say and walk along with people as they work through past experiences and give them opportunities like the Dismantling Racism workshop,” Connie White says, “we can do some amazing things.”

Little Rock, Arkansas

The Women’s Project

Spending Privilege — or — Putting Your Ass at Risk

Founded in 1981, the Women’s Project organizes community education and political action to confront violence against women, children, and people of color, women’s economic issues and social justice concerns. These include sexism, racism, homophobia, ageism, ableism, classism, and anti-Semitism. While this may seem like an impossible range of issues for one organization to tackle, the project’s founder Suzanne Pharr believes that the issues are intertwined. With this awareness, the Women’s Project has achieved considerable success.

According to Pharr, the Women’s Watchcare Network, which monitors and responds to incidents of racial, religious, sexual and anti-gay violence, illustrates best the way the project unites groups in a common cause.

“We bring together people who have experienced religious violence, like Jews and Catholics in the South, people who have experienced sexual violence, like lesbians, and people of color who have experienced racial violence. We have them tell their stories, and out of that people understand their commonality.”

The project also works in the Arkansas state prison for women, training prisoners to do AIDS education with fellow inmates, sponsoring an ongoing support group for battered women in prison, and coordinating a program to transport children to visit their mothers on weekends.

The prison visitation program is made possible through the work of United Methodist Church women throughout the state who provide the transportation. These volunteers are, for the most part, white and middle class.

According to Pharr, the idea of what she calls “spending privilege” is the underlying philosophy of the Women’s Project. “If you belong to a group that has historically been dominant and has been the proponent of injustice, you have to do a lot to demonstrate that you’re willing to put your reputation, your character, your life at risk on behalf of those who have been the recipient of that injustice. You have to be a traitor to your whiteness.”

Pharr contrasts spending privilege with paternalism: “Paternalism is acting in a kind of caretaking way. Spending privilege is putting your ass at risk. When we go to Klan events we are in physical danger. When we take on issues that are volatile, we get threatening phone calls.” Pharr has had her home broken into.

There is also the issue of heterosexual privilege. There is a common assumption among outsiders that everyone who works for the project is homosexual because some of the work focuses on gay and lesbian issues. Lynn Frost, a Women’s Project staff member (project staff do not have titles) explains that the heterosexual women on the staff have never been afraid to have the public suppose that they are homosexual.

“I think African-American women on our staff and board who go to press conferences in support of gay and lesbian issues put themselves at risk of losing all their heterosexual privilege in their communities,” Pharr says. “The risk is not physical, but it hurts like hell.”

The social justice work encompasses the Women’s Project staff who believe it is necessary to “walk the talk.” Frost explains that the project tries to maintain a staff that is half women of color and half white. More than half of the board members are women of color.

Everyone who works for the Women’s Project is paid the same, from the founder to the graphic artist who is hired on a contract basis to the people who clean the building. At the Women’s Project, every woman’s time is of equal value. All of the full-time staff are given equal access to decision making, and no one is spared the tedious jobs like putting on labels.

Although the Women’s Project has been successful in uniting people across sexual preference, race, and socio-economic disparities, Pharr is concerned about the future. She feels that we are living in a time in which the political right wields great power. “They have been very successful in working along the fault lines of racism, sexism, and homophobia,” she says. “Scapegoating allows fascism to develop. It contributes to our failure to look at the true causes of our problems.” The work of the Women’s Project and other progressive grassroots organizations, she feels, will be hard and results a long time coming.

“Cornel West, a black theologian, expressed it for me when he said he could not feel optimism,” Pharr says. “There was nothing in his recent experience — or long-term experience — that would indicate that things are going to get better. There are massive forces that are moving, but at the same time, he was a person of hope. Hope is where you leap over the events that you see and maintain courage and keep going.”

New Orleans, Louisiana

St. Thomas/Irish Channel Consortium

Talking to Mama and Papa

The St. Thomas housing project in New Orleans is one of the poorest in the nation. St. Thomas has 1,500 housing units, but a third of them are boarded up. The residents, according to Barbara Major, chair of the St. Thomas/Irish Channel Consortium, are 99 percent black. Ironically, St. Thomas is located in a section of New Orleans which includes the lower Garden District, home to some of the wealthiest “old money” families in the city.

For years, St. Thomas has been a magnet for a wide variety of social service providers, but the residents and leaders of St. Thomas were never included in the decision-making process. Five years ago, St. Thomas residents, who have a long history of tenant-rights’ organizing, said “enough.” Agencies serving the community were told it was time to renegotiate their relationship with St. Thomas.

“Even though money and services had come into the community, things hadn’t gotten better. They’d gotten worse,” Major says. “The resident council of St. Thomas told these institutions, ‘if you are unwilling to come to the table, we are willing to go to the funding agencies and ask funding to cease and desist.’”

The agencies came to the table — not only because they were threatened but because they, too, were frustrated. They wanted to help, but their best efforts were not producing results. From the ensuing meetings between the residents of St. Thomas and community service providers, the St. Thomas/Irish Channel Consortium (STIC) was formed.

The consortium crosses age, race, and economic barriers. Residents work side by side with members of the wealthy, predominantly white Trinity Episcopal Church and representatives from predominantly white service organizations. It is not a case of whites “doing” for people of color, however. The consortium has made it clear that the people of St. Thomas will provide the leadership.

There is one prerequisite to joining the consortium. Each member must participate in an “Undoing Racism” workshop, which is conducted by the People’s Institute in New Orleans. As Major describes it, the workshop is not only about how white people deal with blacks but also about how whites deal with whites and how black people deal with other black people. The workshop also helps blacks understand how racism is internalized.

“Racism had to be understood in order for us to understand our community,” Major said. “We understood if you had half white and half black, there was already an imbalance because the African- American community had been left out of the loop. We had no institutions, no computers, and we didn’t have staff.”

The workshop is not about blame and guilt, Major says. “You’ve got to talk to people — not in a way to tear them down or rip them apart — but to call them to some consciousness. It’s a natural thing for whites to resist black leadership. It’s part of the social process. It’s not about white people being bad. We’ve only been able to stand together because we put racism out there and began to grapple with it.”

Together white and black members attend board meetings, work, and socialize. And together they have produced some model achievements.

One is the Kujichakalia (Kuji) Center which means “self-determination” in Swahili. The center serves St. Thomas’s young people. At the outset, the consortium decided the center would not become another large social service bureaucracy. Rather than creating new services for the center, the consortium contracted out to existing community institutions.

“That center came out of the community,” Major says. “All we do is from the bottom up. We wanted a safe place where our kids can learn about themselves, where they can talk to their mamas. And not only their mamas but their fathers, too, because we emphasize the visibility of men in our community. We’re talking about parents that nobody talked to while they were growing up.” One of the significant issues, says Major is, “they haven’t learned the skills they need to communicate about sexuality issues.

“But it’s not enough to have a Kuji Center. We have to infuse the principles of the center in our schools where our kids begin to act and react differently. We developed a solid Afrocentric curriculum for our own kids. Our goal is not to create just services but to transform institutions.”

The center’s holistic approach to addressing teen pregnancy has been used as a national model. Early in the consortium’s development, St. Thomas was approached by a local funder looking for a collaborative process to develop a teen pregnancy prevention program.

“We said we might be interested in applying but we said there had to be some different principles involved,” Major explains. “We decided we would not apply to any foundation that sees teen pregnancy as our number-one problem — because it’s not. Teen pregnancy is an offshoot of structural problems. We wanted to look at racism and leadership development.” Once assured, STIC applied for and received the grant in 1990.

The consortium was also awarded a three-year, $1 million grant by the Casey Foundation in 1992 to become one of seven sites in the country to take part in a new initiative called “Plain Talk.” “The program addresses the needs of sexually active young people and how you create a healthy community,” Major says. “You look at the problem holistically. HIV and AIDS are being transmitted earlier. Just saying ‘no’ is not the only thing we must do for those saying ‘yes.’”

The idea of the consortium, Major says, is to create a sense of family in the midst of, as Major calls it, “the most family-insensitive culture ever known.” She is speaking “of the family of man.”

“We must develop the minds, souls, hearts, and bodies of the people that are part of the community,” Major says. “It’s a feeding for the community. We’re not only gonna be all right, we’re gonna go beyond that. Damn, we can do this.”

JONAH

416 E. Lafayette

Casey Building, 1st Floor

Jackson, TN 38301

(901)427-1630

The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond

1444 N. Johnson

New Orleans, LA 70116

(504) 944-2354

St. Thomas/Irish Channel Consortium

624 Louisiana Ave.

New Orleans, LA 70115

(504) 895-6678

Save Our Cumberland Mountains

P.O. Box 479

Lake City, TN 37769

(615) 426-9455

Southern Empowerment Project

343 Ellis Ave.

Maryville, TN 37801

(423) 984-6500

The Women’s Project

2224 Main St.

Little Rock, AR 72206

(501)372-5113

Tags

Janet Hearne

Janet Hearne is a free-lance writer in Johnson City, Tennessee. Her fiction appeared in the summer 1995 issue of Southern Exposure. (1996)