Moonlighting for Justice

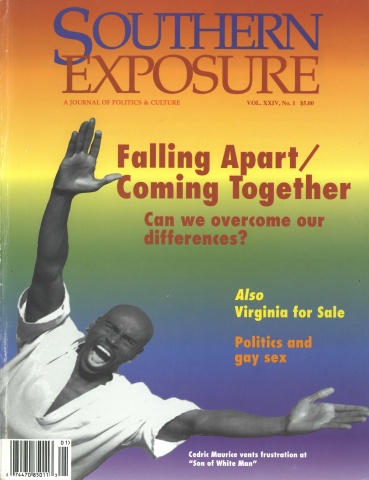

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

Bettye Cook, a petite woman with her right hand and arm encased in a permanent brace, doesn’t like to talk about her workplace accident. She speaks softly, fighting back tears, as she tells about working with improperly loaded rolls at the Brevard, North Carolina, Ecusta paper mill.

“My supervisor was with me, trying to keep the coils from slipping off the machine,” Cooke said. “It was 6 p.m. and I was behind. I kept telling her how dangerous it was, but she told me to put shims in and to speed it up so I could get caught up.

“And that’s exactly what I did. The very first bobbin I put on and speeded up, the machine exploded. Next thing I know, I was back against the wall six feet away, and parts of the machine had flown 12 feet away. My hand was all drawn up, I couldn’t move it.”

Cooke suffered electric shock and burns that required extensive hand surgery. “The day after surgery [the company] took me from the hospital back to work,” she said. “I laid in this little room for two days with a small couch and a commode. All I did was cry and throw up. Monday morning they took me to the plant medical center, and I laid there for two weeks. They wanted to protect their safety record to keep it from being a lost-time accident. In the meantime, I lost 18 pounds and my hair fell out.”

Cooke was unable to lift more than one pound or do repetitive work. The company could not find a job for her, she said. “I went from July to December without a paycheck,” she said. “The company said I went out because of my nerves and not with my disability, so it wasn’t their fault. But it is their fault I can’t do anything because my hand doesn’t work.”

Pat Sweeney, public relations manager for Ecusta’s parent company, P. H. Glatfelter in Spring Grove, Pennsylvania, said that the company does not comment on individual accident cases.

But she said the Ecusta plant has an exemplary program for safety. According to Sweeny the plant has received safety awards from the North Carolina Department of Labor for 22 consecutive years. “We comply with all state and federal regulations and go beyond to make sure our employees have a safe working environment,” Sweeny said. “We have what we believe is a very good program.”

Cooke had earned $12 an hour at Ecusta and worked two other seasonal jobs to save money for her three children. The money is now gone.

From a friend at church, Cooke learned about Injured Workers of the Carolinas, a two-year-old project of North Carolina Occupational Safety and Health, a private, nonprofit membership organization of workers, union locals, and health and legal professionals. IWOC and NCOSH provide training and technical assistance to workers on job safety and health.

Injured Workers of the Carolinas is run by volunteers who help one another through the maze of government requirements, industry mandates and the waiting — especially the waiting. Even an uncontested case can take eight months, while a contested case can take more than two years, according to John Hensley, an attorney specializing in Workers’ Compensation claims.

One of IWOC’s missions is to walk people through the complex rules regarding workers’ compensation. IWOC encourages employees to look out for themselves and not to assume that the company will take care of them.

NCOSH reports that each year 100 to 200 workers are killed on the job in North Carolina; 2,000 men and women die from occupational diseases; more than 9,000 new cases of occupational disease strike the state’s workers, and more than 130,000 workers are injured on the job.

Jerry Stewart, president of the local United Paper Workers Union at Ecusta, has more than 20 years experience with union work and believes that most companies are going to do whatever they can to keep costs low. He believes downsizing contributes to an increase in accidents on the job. “I tell workers to do their job, and if it takes more than eight hours to do it right, don’t take shortcuts and break safety regulations,” he said. “For the company, the bottom line is always money.”

With the support of IWOC and her attorney, Cooke is presenting her claim before the North Carolina Industrial Commission, a board appointed by the governor to oversee the Workers’ Compensation Act. Congress first enacted the Act in 1909 to assist anyone hurt on the job. Most states, including North Carolina, have enacted their own workers’ compensation acts as well. Workers’ compensation benefits pay all medical expenses and wage loss compensation at the rate of two-thirds of the average weekly salary (based on the past 12 months).

Worker Loyalty, Company Profits

Vickey Utter, chair of the board of directors of IWOC, sometimes wears a large button that reads: “Why is the right to die on the job the only right freely guaranteed to workers?”

Utter knows her subject well — she is a two-time survivor of workplace injury. “In 1978, I was working for Buncombe County Parks & Recreation when my hand was crushed between a tractor and a scraper,” she said. “It took six surgeries to fix it. I was supervising 20 people then and felt responsible for my staff, so I went back to work immediately after the first five surgeries.

“One winter day, I was out working with my crew, and it started to sleet. The temperature kept dropping. One by one the staff started to go home. They told me they weren’t paid enough to work in this kind of weather. I kept working because I wanted to finish the job. All of a sudden the pins and wires in my hand literally froze, and my fingers were locked around the pliers.”

Utter drove herself to the doctor, fingers cramped around the pliers. Her hand needed more surgery, but this time the doctor refused to perform it unless she took time off. “I didn’t go back to work right away, and they fired me for not being able to do my job,” she said.

No one at Buncombe County Parks & Recreation could comment on Utter’s 1978 injury.

Utter’s own experience working while injured makes her extra-sensitive about the subject of malingering — workers pretending to be injured to collect benefits. “It’s not as prevalent as ‘Prime Time’ or ‘60 Minutes’ would lead us to believe,” she said. “They don’t put the real thing on [those shows]. It doesn’t attract as many viewers. Besides, Southerners are different. I’ve known workers to take all kinds of abuse and go home and be sick there, complaining only to their family because that’s the way we were raised.”

Statistics back up Utter. North Carolina paid $11 million in lost-wage compensation, or 43 percent of the national average of $26.5 million per state, according to a 1988 study in Workers’ Compensation Monitor, a private newsletter. North Carolina ranked 43rd out of 45 states reporting, the study found. The state is the nation’s 10th most populous. The state paid $10.5 million in medical costs as compared to the national average of $16 million; only nine states paid less, the study found. Other low-ranking states included Tennessee, Virginia, South Carolina, Indiana, Kansas and New Jersey.

No-Fault, Low-Pay Insurance

Prior to enactment of the 1929 North Carolina Workers’ Compensation Act, people hurt on the job were often fired with little recourse. The act was designed to provide broad coverage, with some degree of compensation to workers who were hurt by accident regardless of fault. Injured employees no longer had to prove employer’s negligence to receive benefits. However, an employee dissatisfied with the Workers’ Compensation settlement had to show more than negligence, according to attorney David Gantt. “If the worker shows that the employer knew with certainty someone would be hurt, the worker can sue,” he said. “That’s way beyond negligence — and it’s not often that a court will hear even that.”

But laws are only good if enforced, and the Industrial Commission does not adequately enforce its own regulations, according to attorney John Hensley. Failure to post Workers’ Compensation information in every workplace, for example, or failure by employers to send in required forms may bring only a $25 fine. Although every employer with three or more workers is required to have Workers’ Compensation insurance, uninsured employers are assessed only a $100 penalty — but anyone injured on their site is left with no compensation. The average fine for serious violations that threaten injury or death is $1,024, according to NCOSH.

When employees don’t feel they’ve gotten just compensation, they turn to fellow workers for support. At a recent meeting of the Injured Workers of the Carolinas, one frail, elderly woman told how the tips of her fingers on her right hand were crushed at work. “I almost bled to death,” she said. “They didn’t even find me a way to Asheville to the hospital. My daughter-in-law lost a day’s work on her own job for taking me. The next day they came and got me. I could barely walk, and they took me to work, me on heavy pain killer. I had to lay down in the locker room and sleep.”

She asked to remain anonymous, afraid she would lose any chance to return to work. “For two weeks they sent the chauffeur to get me,” she said. “They kept me there because they didn’t want a lost-time accident.”

She is now back at work, operating a grinding wheel with only cloth gloves to protect her hands — against doctor’s orders, according to Utter. She feels coerced and intimidated, fearing the company is trying to force early retirement on her. Utter has heard dozens of stories like this one.

“Most people have to pay bills, feed kids — you’ve got to find a job even if you are dying,” she said. “They don’t treat dogs like this. They don’t treat criminals like this. That’s what IWOC is all about — trying to get it into people’s heads that they are human, that they do have rights.”

SIDEBAR

Workers: Know Your Rights

By Betsy Barton

Betsy Barton is training coordinator with North Carolina Occupational Safety and Health Project (NCOSH).

What are Workers’ Compensation benefits?

Benefits should be paid to workers who were hurt on the job or made sick because of their work. Benefits cover all medical expenses and compensate for lost wages if you cannot work. Laws vary from state to state.

What if you are injured or become ill from your work?

1. Take care of your health. See your doctor and state that your problem is work-related. Show the doctor how you do your job, and tell him/her about chemicals, dusts, noise or other hazards you work with. If a doctor thinks you should not work, or work only with restrictions, get it in writing and keep a copy. Do not leave work, or you can lose your rights!

2. File the required notification form with your state’s Workers’ Compensation Commission. This form is simple and serves as an official record that you were injured. Be specific about your injury or problem. Keep a copy for yourself and give one to your employer. You can lose your right to workers’ compensation benefits if you do not notify your employer in writing, usually within 30 days, depending on the law in your state. Your employer is required by law to file a separate form to notify the state, in addition to any paperwork that they file with their workers’ compensation insurance carrier.

3. Keep written records. Collect information and copies of everything. Write down exactly what happened. Get names and addresses of people who can corroborate your story.

4. To remain eligible for workers’ compensation benefits, you must see the health care provider your employer suggests, take the treatment or therapies recommended and go back to work when the doctor sends you. In some states, you may be entitled to a second opinion, but you may have to pay for it yourself and apply to the Commission for reimbursement.

5. If your employer refuses to pay you benefits, you can request a hearing with the state Workers’ Compensation Commission. This can take a year or more. You should have a lawyer if you appeal because the law is complex and your future benefits are at risk. Both you and your employer are entitled to appeal the case to the Commission.

Protect Your Rights

• File your claim before the deadline in your state. Often, you have two years — once you’ve realized that the problem is work-related — to file the claim. After that, you lose your rights.

• Get advice from a worker advocacy group or an attorney who specializes in workers’ compensation before you make major decisions about your case. (See Toolbox section for groups in your area.)

• Don’t accept a clincher, or lump-sum agreement, without getting advice from a lawyer. If you sign a clincher, you give up your rights to any future claims regarding that injury or illness.