This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

The problem wasn’t that performer Ed Haggard took off his clothes during his one-person show, a section he called “I’m too white,” and smeared his body with blue paint. It was what he said while he was doing it. He said that if he had more color, he might have a sense of rhythm, a love of nature. He painted his genitals and said if he had more color he might be more virile.

Haggard was excerpting a few scenes from “Son of White Man” at the Alternate ROOTS (Regional Organization of Theaters South) annual meeting, aiming to get comments and bookings. He had performed the show about growing up in Nashville, Tennessee, to good reviews at fringe theater festivals across Canada and around the U.S. Last summer, when he tried it out at the meeting of grassroots performers and theaters, someone in the audience booed. No one had ever booed before.

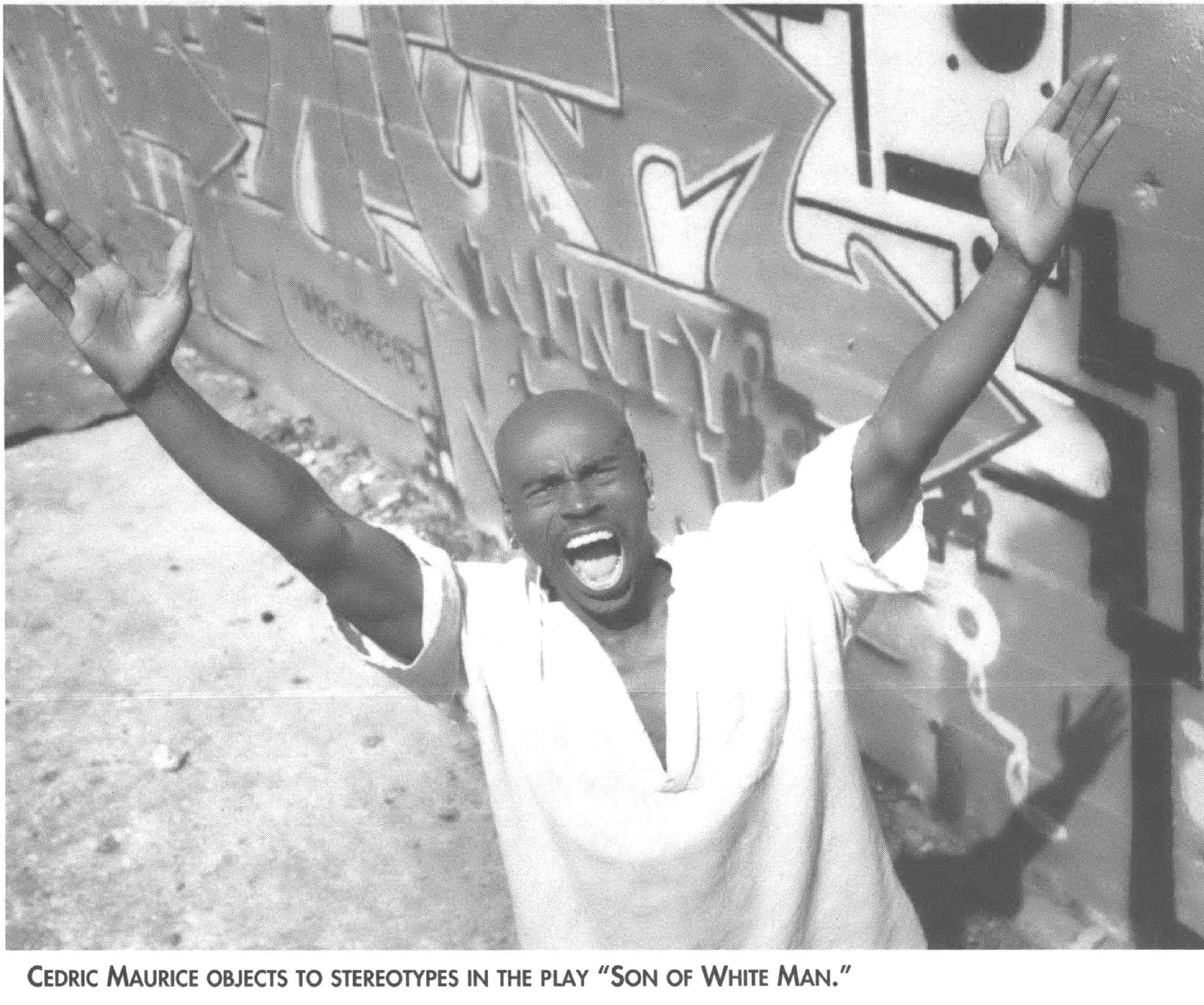

Another man, Cedric Maurice, a black dancer from Atlanta, shouted, “That shit was fucked, Ed!”

It wasn’t the first time the audience erupted over racial stereotypes after a performance at a ROOTS annual meeting. The weeklong gatherings in the mountains are intended to create a safe place for performers to try out new work, but over the years the scene has sometimes become fractious.

Political Theater

Alternate ROOTS is a noble experiment that keeps bumping into its own politics. The “Alternate” in their title represents their vision or attitude; they are emphatically not mainstream. According to most universities and museums, art transcends politics and social conditions. Political art isn’t art. To those in ROOTS, art is always political. A stark metal sculpture or a painting of Elvis Presley on black velvet reflects and amplifies the class and culture from which it comes. ROOTers not only accept the political in art, they embrace it. They create art to build awareness, understanding, coalitions, and fires in their communities. At the same time they’ve tried to make an organization that serves artists from different races, backgrounds, and sexual orientations. They have struggled on both counts.

Nearly 20 years ago, the research and organizing school, Highlander Center in East Tennessee, hosted the organizing meeting for Alternate ROOTS. For years Highlander had provided civil rights, labor, and environmental groups a seedbed to organize for social change.

The Appalachian playwright and poet Jo Carson coordinated the meeting, inviting every theater organization she could think of in the South: university theater departments, community theaters, and professional companies that created original plays in their communities rural, urban, black, mountaineer. They included groups like Roadside Theater from Whitesburg, Kentucky, a troupe that made drama from local stories, and Carpetbag Theater from Knoxville, Tennessee, telling of the African-American experience.

The universities and community theaters stayed away from the next meeting. The small innovative theaters returned. It had been lonely work for these scattered groups. In the early days “we barely knew that we were part of a long tradition of people’s theater,” said Dudley Cocke, director of Roadside, in High Performance, a magazine of “contemporary issues in art, community and culture.” In Alternate ROOTS they found a sense of community and a place to show work to their peers, to share experiences, and help get grants to keep on going.

John O’Neal was an early member of ROOTS and served as board chair in the 1980s. He had established the Free Southern Theater in 1963 out of his civil rights work in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “Our objective was to make art that supported and encouraged those involved in the Southern freedom movement by, for, and about black people,” he said. He found in ROOTS “different constituencies in an exciting dialogue (about) ways they could contribute to each other’s development. It was exciting to participate, exciting for audiences. It had forms of energy that the movement had.”

Over the years, Alternate ROOTS expanded to include individual performing artists, writers, musicians, directors, and visual artists. Today there are 71 member theaters and 109 individual members (who do not belong to a company). An office in Atlanta and a small staff help members to find places and funding for performances and to create partnerships with schools and community groups. The staff has put together an occasional theater festival, and they organize the annual summer meeting that brings together nearly 200 members, aspiring members, friends, and children. Usually they meet on the grounds of the former art school, Black Mountain College in North Carolina, a rustic mountain camp. There they try out new material, commiserate about funding, and dance, sing, eat, play — and whether they had planned to or not — argue.

Bomb I

Nine years ago at an annual meeting in the North Georgia mountains, a performance jarred everyone’s complacency and sense of shared purpose.

Margaret Baker wanted to try out some of the characters she was developing — this was aside from acting with the Road Company in Johnson City, Tennessee. In one short piece, she became a Sunday School teacher in the “Rock ‘o’ My Soul in the Bosom of Just About Anybody Except a Minority Baptist Church.” In a broad satire, the white actor told the story of Moses and mixed it up with the story of Little Black Sambo.

Most of the ROOTS’ audience responded warmly. “I was laughing at it,” remembered ROOTS executive director Kathie deNobriga, who is white.

In the feedback sessions, two black members of the audience who were attending a ROOTS meeting for the first time, playwright Pearl Cleage and performer Zeke Burnette, expressed outrage. They were offended and hurt at the use of a hateful racial stereotype. Using a cultural image like Little Black Sambo carried with it more power than Baker had understood, they explained. Most offensive to them was that the largely white audience had laughed at the performance.

“Pearl and Zeke and several other African-American members of the audience for Margaret’s piece were thunderstruck that they were in an audience which had been presented as anti-racist who were laughing at things they perceived as racist,” explained Bob Leonard, co-artistic director of the Road Company and one of the founding members of ROOTS. “My perception was that Margaret lit what she thought was a sparkler, and it was a hand grenade.”

The discussion was painful. Baker cried, and the critics said that her tears took the focus away from the issue she had raised. This shouldn’t be about her, but about what had been unleashed. They had been hurt, a deep cultural hurt that extended back 400 years. They wanted that hurt acknowledged.

It was a transforming day for some of the white people in ROOTS. “What I can remember was this big field, and a couple of people spoke with a great deal of passion and anger and said we were all racist. Words weren’t minced at all,” said Christine Murdock of the Road Company. She remembered Cleage saying, “My friends back in Atlanta told me I was crazy to go to the North Georgia hills and hang out with a bunch of white people.”

“There was a lot of collective white guilt. There was also the horror of realizing I had no idea. It was just a heartache,” said ROOTS director Kathie deNobriga. Margaret Baker said she cried for such a long time that “somebody went and got John O’Neal, and he knelt down in front of me, and he said, ‘Margaret, you are not the cause of racism in this world.’ He said, ‘You’re good, but you’re not that good.’”

The wounds ran deep. Cleage and Burnette left and never returned to ROOTS, though they have remained performers in the South.

“I think what was so emotionally devastating for me was the people I wanted to defend I ended up offending,” said Baker recently. “I think I came out of it with a clearer understanding of why Whoopi Goldberg is perfectly fine to say certain things it isn’t too cool for me to say. Now I realize why it was offensive.” She has not and will not perform the piece again, and, for better or worse, she will “never, never, never” address race in her work again.

The lessons for some of the other white audience members that day altered ROOTS’ — route.

Rerouting Roots

After hours of discussion following Baker’s performance, the members drafted a resolution that the executive committee deal with racism when discussing and planning programs. In the early ’90s, ROOTS began to hold racism workshops and seminars at its annual meetings.

The members also added a provision to the rules that those wishing to join must say how their work related to the social and economic justice goals in ROOTS’ mission statement. Until then, the organization had operated on the dictum elegant in its simplicity: “Who comes, is.” Any individual or group who attended a meeting could stand for membership if they came back to the annual meeting the next year. The openness meant that newcomers often disrupted ongoing discussions, and that continued to be a problem.

Almost every summer, another incident upset and alienated people. A conflagration erupted in 1989 when a white woman who has made a career of African drumming, stood for membership. That year, Deborah Hills, a black labor-based organizer, had come to do workshops. As drummer Beverly Botsford described how she would carry out the mission, Hills “just stopped the meeting and took her finger and pointed it at Beverly and spoke a curse, stating that drumming is a male African activity, stating that no woman should drum, and no white woman should drum, and when anybody does, they are calling up the horror of the gods,” remembered Bob Leonard.

“It was like somebody stabbing a knife in my heart and twisting it in,” said Botsford. Paula Larke, an African-American woman who also drummed, “threw a conga across the room and stormed out,” said Botsford. “The whole meeting just fell apart.”

The challenge brought up issues of cultural appropriation. Should Botsford practice an art from a different culture? Who can adapt and revise traditions? The group’s sympathies generally stayed with the women who drummed, but “It was a very rough encounter with no resolution. We managed only to get through the week. Beverly was accepted in despite this curse,” said Leonard.

A Six-Step Program — or — Process Process Process

ROOTS needed a way to resolve hot situations. Part of the solution came with a method to critique performances. For the past several years, a white dancer, Liz Lerman, had been developing what she called the “critical response process” to give fellow artists feedback in a useful, non-threatening way. Along with other groups around the country, ROOTS adopted the method in 1993.

“We’ve always had trouble with how we critique each other. The point of it is to help the artist,” said the Road Company’s Christine Murdock.

A facilitator who knows the process is necessary. The first step is praise from the audience because “people want to hear that what they have just completed has meaning to another human being,” wrote Lerman in an article about her process in High Performance. She doesn’t recommend a comment like “that is the greatest thing ever,” but does suggest “words such as ‘when you did such-and such, it was surprising, challenging, evocative. . . .’”

In the second step, the artist asks questions, and these must be specific, for instance, “Did that hat fit the character?” “When the artist starts the dialogue, the opportunity for honesty increases,” wrote Lerman.

In the third step, the audience asks the questions, which must be phrased in a neutral way. “Instead of saying, ‘It’s too long,’ a person might ask, ‘What were you trying to accomplish in the circle section?’” explained Lerman. While this might seem a “ridiculous task if criticism is the point,” Lerman said, the nonjudgmental approach is much more useful to the artist than unbridled opinions. “I can say whatever is important through this mechanism, and what I can’t say probably couldn’t be heard, or isn’t relevant,” wrote Lerman.

The fourth step is what Lerman calls “Opinion Time.” Here the audience may say what they think, but they must first ask if the artist wants to hear it. “I have an opinion about the use of nudity in the last scene. Do you want to hear it?” is the structure that Lerman uses. This method keeps the artist in control of the process.

The session generally ends after “Opinion Time,” but two steps can be used when more discussion seems called for:

Step five is “Subject Matter Discussion.” Here the audience and artist can talk about the content of the work. The performance may also inspire stories and memories that audiences can share at this time.

Step six, “Working on the Work,” involves digging into the actual structure, revising specific parts, and trying out new ideas.

The feedback works particularly well among groups of fellow artists, such as those at the ROOTS annual meetings, and over the past three years, ROOTers have embraced the process.

It has taken adjustment. At the 1994 annual meeting, a group including Adora Dupree, an African-American storyteller who is also chair of the ROOTS board of directors, presented a case study of the “Selma Project.” This was a collaboration developed with Bob Leonard of the Road Company along with the director of the arts council in Selma, Alabama, who is, like Leonard, a white man. Seven artists, black and white, came from around the South to work with Selma agencies. Children produced poetry books and performances with artists coordinating.

“Bridges were made between black and white arts groups,” said Leonard, who also teaches directing at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg.

Dupree found herself in an uncomfortable spot when some black people at ROOTS described Leonard and the Selma arts council representative as “‘two white boys exploiting the black community.’ I took great offense at that because I was one of the artists, and I didn’t feel exploited at all,” said Dupree. She felt that her involvement informed how the project was carried out.

The critical response process, meant for feedback after performances, wasn’t planned, but the group agreed to try it out before the situation became too volatile. The facilitator, who didn’t understand the process very well, “started to depart from the critical response facilitation because she felt it was keeping people from saying things they wanted to say,” said Dupree.

That is the idea, though, explained the storyteller. When people say exactly what they want, they can become too hot, too personal. The process provides a way to give the artist information about how a piece comes across, not a way to vent anger. Anger has not proved useful.

Because the discussion was beginning to spin out of control, Dupree asked a more experienced facilitator to continue the discussion, but there had been damage.

Bomb II

“Son of White Man: the Naked Truth” by Ed Haggard could have been designed to test how far Alternate ROOTS had come. Just the day before the performance, the New Orleans-based People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond had conducted an anti-racism workshop. ROOTers were sensitized and ready.

Cedric Maurice, who is a member of the ROOTS executive committee, surprised himself with his outburst at the end of “Son of White Man.” He was not pleased because he had wished to maintain control, to respect the process. “My reaction was very spontaneous. I’ve never been overtly slapped in the face with anything as overtly offensive as what I thought I was seeing.”

Maurice had actually expressed how most of the audience, black and white, felt about the end of Haggard’s piece. Some 75 people stayed after the performance to discuss it. They seemed ready to shout invective, but everyone followed the process. “There was a lot of positive feedback,” said actor Christine Murdock. “It must have gone on 15 to 20 minutes.” Cedric Maurice even contributed.

Haggard asked several questions, including ones about the nudity (which wasn’t seen as a problem, probably because a chair had been strategically placed in front of him). He didn’t ask what had disturbed them at the end. There was no way to address this volatile issue in that stage of the process unless the artist brought it up.

In the third stage, when the audience asked questions, they found themselves stymied. “Nobody could get at it — that he was insulting,” explained Murdock.

Finally Haggard asked, “Were you insulted?” This opened up the discussion.

Like Margaret Baker, who had performed the piece about Little Black Sambo, Haggard had believed that his work tackled racism, rather than reinforced it. He hadn’t meant for the painting of his body and wishing for “more color” to contribute to racial stereotypes, positive or negative.

Even with the reasoned processing, the artist could sense the anger and anguish around him. “After we’d done the first step, and we were going into the second, he had to take a minute just to catch his breath, tears coming down his face,” said Murdock. After the third step, Haggard departed, exhausted. Later he said he felt like “a couple of people acted like bullies. I think there’s lots more to this story than simply Ed Haggard is a racist. It felt like these issues were being channeled through me. I’m a pretty loving kind of fellow. It should be clear I don’t support any racism, classism, homophobia,” he said. But he did appreciate the “tremendous positive response” that he received during the first part of the process.

After Haggard left, almost everyone else stayed until 3:00 a.m. and continued talking about racism and Alternate ROOTS.

Kathie deNobriga, executive director of ROOTS, thought the process worked. “We were successful for the first time in applying our intellectual skills to an emotional response. We held a really principled discussion. There were some honest emotions that didn’t stop the discussion.”

“It was certainly passionate,” Murdock said.

“I like the critical response process. It’s supposed to be artist-driven. It feels safe,” said storyteller Adora Dupree, who is a former member of Carpetbag Theater in Knoxville. “I get to say, ‘I don’t want to hear that now.’ A lot of times people (audience members) want to dump their stuff on the artist.” Dupree wants to know how her work comes across, but it’s not always easy for an artist to hear criticism. With the process, she knows she won’t be verbally abused. “I want to know that I’ve communicated. I want to know what the work evokes.”

Racism and White Liberals

While ROOTers generally like the critical response process, they can’t use it to set the organization’s agenda or structure. Like many progressive organizations with diverse memberships, ROOTS wants to be inclusive and democratic. In order to build a model that will show the way, however, they must first address fundamental assumptions about race, class, culture, sex, and sexuality.

ROOTS sees racism as its defining issue — though black members and white members have differing visions of it. It seems that it’s many of the white ROOTers struggle and obsession. They wish not to be simply a white liberal organization, and more than one call themselves “recovering racists,” though they’ve been liberals for most or all of their lives. Their experiences in ROOTS have made them realize that they’ve missed something, and they’re trying to figure it out. The blacks in ROOTS have dealt with this white liberal guilt with varying degrees of patience over the years.

Cedric Maurice, who lashed out at “Son of White Man,” saw the issues clearly last summer: “When Ed presented that work, he peeled the scab off of the wound that has existed over Alternate ROOTS over all of these years. Some piece comes up that causes everybody to get into this psychological gnashing of the teeth. The agenda winds up getting put aside, or people feel put off because their concerns aren’t being addressed. A lot of people wind up walking away with some misgivings, and a lot of people don’t come back.”

For some of the blacks in the organization (and for some blacks no longer in ROOTS), it’s inadequate that some of the white members understand some of their racism. Awareness, interest, and guilt do not represent a paradigm shift. Even when blacks have assumed leadership in ROOTS, they have encountered an institutional structure that resembled a less socially conscious world. After four years as chair of the board in the mid-1980s, New Orleans storyteller John O’Neal (who is also a contributing editor to Southern Exposure), felt that his political needs were not going to be met by ROOTS. “The organization seems obliged to serve members who are overwhelmingly white middle class. I don’t see how they’re really effective at providing leadership because of the nature and the legacy of racism in the South. The political vision they seem to be driven by would be satisfied by just reducing the evidence of antagonism and not necessarily helping people confront and solve problems.”

His current group, Junebug Productions, still maintains membership in ROOTS but has “addressed a lot less energy” to the organization.

There is no theater organization for people of color, so ROOTS does fulfill a role unavailable elsewhere, pointed out Durham arts organizer and Southern Exposure contributing editor Nayo Watkins, a black woman. Even when blacks have served on the executive committee and as chair, “It hasn’t transformed it into a people of color organization nor has it transformed the perception of equity. ROOTS is still a white organization. Whether it is going to be a viable place for people of color to come to” continues to be an issue, said Watkins. “Blacks in the group don’t really set the agenda,” she said.

Watkins does see progress. “I would evaluate it from how far it’s come.” But she finds the confrontations and the intensity at the meetings almost too much. “The meetings are wild. The atmosphere (at the camp) is so beautiful, and you can have great fun, but, you know, those damn issues come up. Just how much more of that stuff can ROOTS take? It really needs to find ways to allow people to say what they have to say and get on.”

“Something’s going on that needs to be looked at, at least if Alternate ROOTS wants to have black people in it,” said Maurice. “I thought Alternate ROOTS was about supporting artists that are about social change, and now all of a sudden people seem to be of the impression that Alternate ROOTS’ job is to combat racism, which seems to me to be another whole organization altogether.”

Message, Medium, and Money

But Maurice has strong feelings about what work from ROOTS should convey. A member of the executive committee, he wants something in the mission statement to ensure that someone with a message of hate would be barred. “We’re not going to sit here with our thumbs up our butts and let them present.”

This was part of the discussion at a ROOTS executive committee meeting in November. When the policy was “Who comes, is,” there could be no question. Though members told how their work contributed to social and economic justice, nothing said they had to show it. Could there be a method of review so that a work such as “Son of White Man” would not be identified as a product of a ROOTS member?

Adora Dupree worries that her own work would no longer find a home under a review. “How do we as an organization decide a work is racist and doesn’t represent ROOTS? I’m really hesitant to go into an era of mission police. If my work comes under that kind of scrutiny, I won’t pass. In my new piece [“Future Traditions,” about her life and relationships] I look at genital mutilation. In cultures where it is a sacred ritual, I would be offensive. Does that make me ineligible to be a member of ROOTS? There’s a piece that’s offensive to my mother. Does that make me a motherist? The only reason we have Alternate ROOTS is because our work offended somebody, because it wasn’t acceptable in a commercial genre.”

The editor of High Performance, which covers innovative theater around the country, worries about the change of focus. “They’re losing track of a shared mission,” said Steve Durland. “If, as a group of artists, they get together and shove the art agenda aside to address racism, then what do people have in common? The primary focus still has to be on the art.”

Lately, though, the primary struggle has been survival. As a nonprofit arts organization, ROOTS is facing severe financial troubles. Government support is evaporating, and artists are scrambling for funding. Foundations and individuals who support nonprofits cannot easily pick up the slack when so many organizations are competing with each other for what funding is available. Being strapped for cash seems to sharpen differences and antagonisms and makes people less tolerant.

In spite of harrowing times, the staff is shaking itself up. They believe that if they wish to be a truly progressive organization, they must operate the way they’d like to see the rest of the world operate. This year, the three employees — one black and two white — restructured to bring more democracy to what had been a hierarchy. It may make a difference.

ROOTS has found a method to discuss their art at least. It is not a smooth process, and feelings still run high. But “Son of White Man” performer Ed Haggard plans to come to the annual meeting this year. He hasn’t decided if and when he’ll perform “Son of White Man” again. Cedric Maurice, the man who shouted at him, will be at the next meeting, too. In fact, the two men are talking about collaborating on a project.

Alternate ROOTS

Little Five Points Community Center

1083 Austin Avenue

Atlanta, GA 30307

404-577-1079

Southern Exposure published a special issue on theater in the South, “Changing Scenes,” in 1986. It features many of the theaters mentioned in this article and is available for $5 from the Institute for Southern Studies, P.O. Box 531, Durham, NC 27702. High Performance published an issue on Alternate ROOTS that includes details of the critical response process. It is available for $6 from High Performance, P.O. Box 68, Saxapahaw, NC 27340.

Tags

Pat Arnow

Pat Arnow, former editor of Southern Exposure and Now & Then, is a writer in Durham, N.C. (1999)

Pat Arnow, editor of Southern Exposure, wrote a play with Christine Murdock and Steve Giles, Cancell’d Destiny, that was featured at a ROOTS festival in 1990. (1996)

Pat Arnow is a writer and photographer who lives in Johnson City, Tennessee. Her short story, "Point Pleasant," was selected "best story" at the Hindeman Writers' Workshop in 1985. (1986)