The Lion and the Lamb

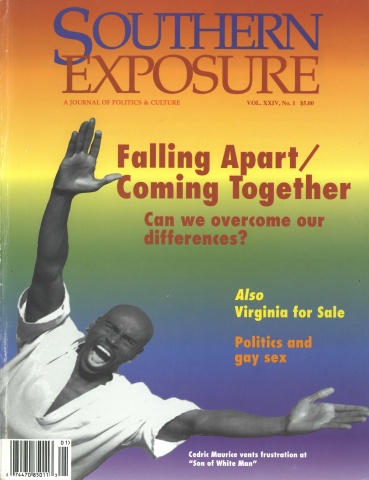

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

In June 1995 the Southern Baptist Convention, an alliance of around 40,000 churches — mostly white — issued an apology for its history of supporting slavery. “For those inside the SBC, it’s a step forward,” says Ken Sehested of the Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America, “but for many, it’s too little, too late. There’s no indication they plan to do much more than issue the statement.”

And E. Edward Jones, president of the 4.5 million member National Baptist Convention of America, a network of African-American churches, asked whether the SBC, founded on the belief in the right to own slaves, issued the apology with a “hidden agenda” of attracting members rather than to set right 150 years of injustice.

Either way, the debate indicates that even the most traditional white churches in the South are starting to confront racism and other -isms within their ranks. While some efforts to deal with race in traditional white churches may be selfishly aimed at trying to increase numbers, revenue, and votes, there are pockets of people in mainstream churches who are looking for genuine ways of crossing lines of race, class, ethnicity, and sexual orientation.

“We want people to know that TV evangelists don’t speak for all Christians,” says Jim Rice, outreach director for Sojourners magazine. The faith-based progressive publication covers a range of justice issues and has published a study guide on white racism (see page 48). Rice says that if they really follow Christ’s teachings, churches have a moral mandate to begin the important work of dismantling racism within the larger society — workplaces, schools, housing, and politics. That’s the only way to achieve meaningful diversity in the church or anywhere else.

The Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America (BPFNA), based in Memphis, Tennessee, and boasting a large Southern membership, tries to do just that. “We try to end the isolation of Baptists concerned with justice by linking them to others,” says Ken Sehested, BPFNA executive director and editor of the network’s quarterly journal, Baptist Peacemaker.

For the past 11 years, BPFNA has connected 1,500 members in 32 regional groups doing grassroots church-community organizing. “Our vision is still to bring the lion and lamb together — red, yellow, black, and white — but we know it will be a lifelong process.”

The BPFNA’s history of facing issues like race, drugs, and domestic violence head-on has gotten the group into hot water. Even the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship (a moderate offshoot of the SBC) cut off $7,000 of BPFNA’s funding when the group supported inclusion of people regardless of sexual orientation. “I now understand,” says Sehested, “how very fearful and disruptive it is to overcome a deeply rooted phobia.”

Within all the mainstream majority-white denominations in the South, there are groups working to ease the fears and create inclusive religious communities. Some try to find ways for a diversity of people to worship under the same roof. Others preserve separate houses and styles of worship. Instead of striving for diverse memberships, they work in partnerships or coalitions toward a goal of separate leadership and worship but shared visions of a just society.

And while progressive people of faith are only a small voice in the wilderness of large conservative denominations, in some cases the voices are leading to some bigger actions — like the Baptist apology.

Here are some examples of the variety of work happening in the South’s largest denominations:

· The United Methodists have intentionally worked toward diversity in their employment practices, hiring people of color and women at all levels of the denomination’s administration. In coalition with other denominations, the Methodists have worked to become more open on the issue of sexual orientation through their Reconciling Congregations program, which is now focusing its educational efforts in the South. Six UM Reconciling Congregations are in the region now and more are in process.

· The Campaign for Human Development (CHD) uses money from special collections in Catholic churches to fund low-income, grassroots, self-help groups across the South and elsewhere, and to educate Catholics on justice issues. CHD Southeast field staffer Bonita Anderson says you can’t work on issues like race without also addressing basic economic needs of low-income people. For example, CURE (Collier United for Rights & Equality), a coalition of Catholic and other churches and local groups in Immokalee, Florida, works with Haitians and Hispanics to secure affordable housing and emergency medical help. CHD makes sure, says Anderson, that in CURE and the other groups they work with, needs addressed are determined by the grassroots constituents themselves.

· Originally an 800-member white congregation, the Oakhurst Presbyterian Church in Decatur, Georgia, now has 175 members — but half of them are black and half are white. “For white folks it meant acknowledging how much we had invested in the system of race,” writes white Oakhurst minister Nibs Stroupe and African-American church elder Inez Fleming in a book on their experiences together in the church. “For black folk, acknowledging these steps (of whites toward change) meant a tremendous step of faith.”

· In the Raleigh-Durham area of North Carolina, at least a dozen African-American and white churches have developed partnerships to work on community issues and celebrate together. Beyond these ongoing partnerships, three Raleigh churches have organized an interdenominational conference for September 1996 to explore racial reconciliation. The group has invited civil rights leader Rev. John Perkins to lead the gathering.

The kinds of justice and diversity issues these groups are pushing into the consciousness of their churches are hard to swallow for some, but for others such issues anchor their faith. As James Preston of the United Methodist Reconciling Congregations asks, “Are we going to be welcoming for all people? That’s what the Church is all about. If we start drawing lines, where are we going to stop?”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)