This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

I grew up gay in the Baptist church. Lonely and isolated, I was an emotional orphan. There was no one I could talk to about being gay. My family and the church would condemn me to hell. My friends would ostracize me and tell my family, and I was too ashamed to discuss this hidden part of myself — my true identity. Yet I longed for some sort of connection.

When I was 10 years old, I believed in heaven and hell. Like everybody in church, I wanted to go to heaven, so I worked towards that end. At age 12, I was saved. After accepting Jesus as my savior and devoting my life to God, I knew I would go to heaven. I was connected to God.

Religion soon became a mask I placed in front of my truth. Sunday school followed by a morning church service, Sunday evening services, Wednesday evening prayer meetings, and a two-week revival twice a year was the regimen. I became efficient at listening to the preacher, hearing what he said, and discussing it with other church members. I could pray with the best of them. I understood the rhetoric and used it to my advantage. Yet, it contradicted the feelings I had for other men and the loneliness I felt.

The messages I grew up with were clear. You didn’t talk about sex. It was a necessary evil. It was something only two heterosexuals, whose visible love was both acknowledged and blessed, used to procreate. I could never picture the “sisters” and “brothers” in Christ fucking for pleasure. When gay sex was referred to, it was with hate. Homosexuals were nothing more than the devil in the flesh. These messages, both spoken and unspoken, served to isolate and confine the part of me that needed to be connected to other men.

When I was 18,1 began exploring what the preacher called “forbidden homosexual acts, lusts of the flesh that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah and would damn a man’s soul straight to hell.” Guided by my raging hormones and a hard dick, I sought relief in the few places in rural Missouri where I could meet men — the local park and adult bookstores.

The back room of an adult bookstore tends to be dark and dingy. There is a tangible odor of sweat and cum, and there are rows of small cubicles that show movies. Sexual tension pervades the environment. You can toss in a token or quarter and watch a couple of minutes of porno. The wall between some of the cubicles has a hole, large enough for men to “connect.” I started having sex with men through these “glory holes.”

At first, the arcades were showing 8-mm movies in each cubicle, and the only sound was the clackety-clack of the film snaking through the mini-projector. The quality of the film, both the filmstrip and plot, was crude and jumpy. Then there was the switch to VHS video and TV monitors. It was amazing — not only could I watch sex between men, but I could hear it, too. Sex between the men on these videos was more than I was able to emulate. Sex through the glory hole was without sound, not a sigh uttered — my orgasm was awash in guilt and shame.

I spent years trying to suppress this part of my life. I denied the simplest realities; I didn’t have sex — let alone enjoy it — with other men. Many times I would notice other “regulars” from the two bookstores in my hometown. I knew that if I were to acknowledge them, I would be acknowledging the part of myself that did not exist — not really. Through the “glory holes” my need for connection was met, without shattering my counterfeit reality — my double life.

Lesbians and gay men talk about their “double lives.” When I was 20, my double life consisted of being the assistant song leader when I was at church, then hitting the bookstore after Sunday evening services. Rather than deal with this dual identity, I spent a lot of time working on my career. In college I would take as many as 18 credit hours, while working 32 hours in the evenings and on weekends. After my certification as a respiratory therapist, I worked 50 to 60 hours a week. School and work were a cakewalk compared to church and sex.

I developed close friendships with both men and women, but I never discussed certain subjects. When friends and family asked about girlfriends, I responded, “It would be very difficult for me to support a wife and family without a stable career, and that is my priority in life right now. If the right person came along, I might reconsider, but until then I have some hard work to do.” (How’s that for feeding into expected gender roles?)

First Time Out

At age 24, I left my rural Missouri hometown and moved to North Carolina for graduate school. I had to get away. I couldn’t explain this then, but somewhere inside me I knew that I had to try to find a way to bridge my worlds. I had to connect my heart to my work, my sexual identity, my political identity, and my spiritual identity. Being at a school of public health made it easy to work on one of the most pressing public health crises in our times — AIDS — a very real and personal issue for me. Though not out of the closet, I was working with and for gay men. I began bridging my identities.

Despite interweaving the personal and professional and creating a network of supportive friends, I was still not able to “come out.” My urge to do so increased over the next six months. I felt like a trapeze artist without a safety net. I was not about to let go of the few friends I had for support without something to catch me.

I spent a summer in Washington, D.C., working in AIDS education at the national headquarters of the American Red Cross. There I saw the positive, pro-active role of the gay community in Washington. I saw a community mobilizing against AIDS. I saw a community proud of itself. I saw a politically active community responding to the unique needs of lesbians and gay men. I began to identify with these new images.

I went to happy hour with a friend from the Red Cross. We were eating barbecued chicken wings and french fries and drinking beer when Peter said, “This is always an awkward question to ask, but are you gay?”

I responded, “Yes, but I’ve never told anyone.” But then, I’d never been asked.

I can’t remember the rest of the conversation, but I remember realizing that I had been honest for the first time in my life. I liked the feeling.

We walked to a gay bar near DuPont Circle, sat outside in a small garden, and talked about him and his boyfriend and about gay things to do in the city. It was the first time I had entered such a world, and I watched as men talked, touched, and laughed. It reminded me of church picnics when friends and family would get together, cook, eat, talk about their families and lives, play softball and Frisbee, and enjoy each other’s company. In this gay bar I felt, for the first time in my life, that I belonged. I had something in common with these men, and it was not related to my spiritual mask.

That same week, I got together with one of my best friends from school who also had a summer position in Washington. She and I had spent hours talking about school, life, and what we would do for a job once we graduated. I had been honest once that week, and it felt good, so I wanted to tell her, too. But I got scared. Those same old messages about how wrong it was to be gay crept into my head, and the truth lodged in my throat. It wasn’t until we started school again that fall that I told her. She smiled and said, “I wondered when you were going to tell me.”

I started telling many of my friends, only to find out they already knew. I found comfort in their support. I even went to the local gay bars for the first time. I enjoyed the freedom of not having to hide my identity in a three-foot by three-foot cubicle.

The first time I went to Boxer’s, a local gay bar, I heard about the gay church here, the Metropolitan Community Church. I couldn’t believe such a church existed. I went. It was a mix of what I call “high church” with its formal ritual and regalia, and a touch of Pentecostal Holiness, where if the spirit moved you, you literally moved, shouted, and praised the Lord. Unfortunately, neither of these forms of worship made me comfortable because they were too close to my roots in the Baptist church. On the other hand, I had never been in a place where it was O.K. to be gay and seek some sort of spiritual meaning for my life.

I’ll never forget a special service hosted by Reverend Delores Berry, a black lesbian. With her commanding presence, she ministered through song and filled the room with tears of comfort and joy. She said one thing that stuck with me: “God made you who you are, and he don’t make mistakes.” From that moment on my true spiritual search began.

With the help of the Baptist church and society, I had spent my life creating an emotional impotence that kept me from connecting with a supportive community. The walls of the cubicle in the adult bookstore kept me in fear and isolation. The confines of guilt and shame kept me from building relationships based on sincerity and honesty. At the same time, this emotional impotence became key to my survival. It kept me focused on my life outside of politics, sex, and spirituality. There wasn’t isolation and pain in my education, career, and superficial relationships. Separating my sexual and spiritual identity from the rest of my life prevented me from going crazy from the fear and isolation. In fact, I can see the times when avoiding my spiritual and sexual realities stopped me from killing myself or contemplating such an alternative.

How could I change feelings of shame, isolation, and guilt? I knew I needed political, spiritual, social, and sexual connections. It was the beginning of my own journey, and it requires both internal and external work and support.

Homophobia Inside and Out

The Metropolitan Community Church allowed me to open up and feel like I was not alone. I met gay men and lesbians and started building friendships. My social situation changed tremendously. 1 went out on dates, had dinner, went to movies, went dancing, and had sex without the walls and a “glory hole.” Before long, I even had my first boyfriend. I was 26 years old.

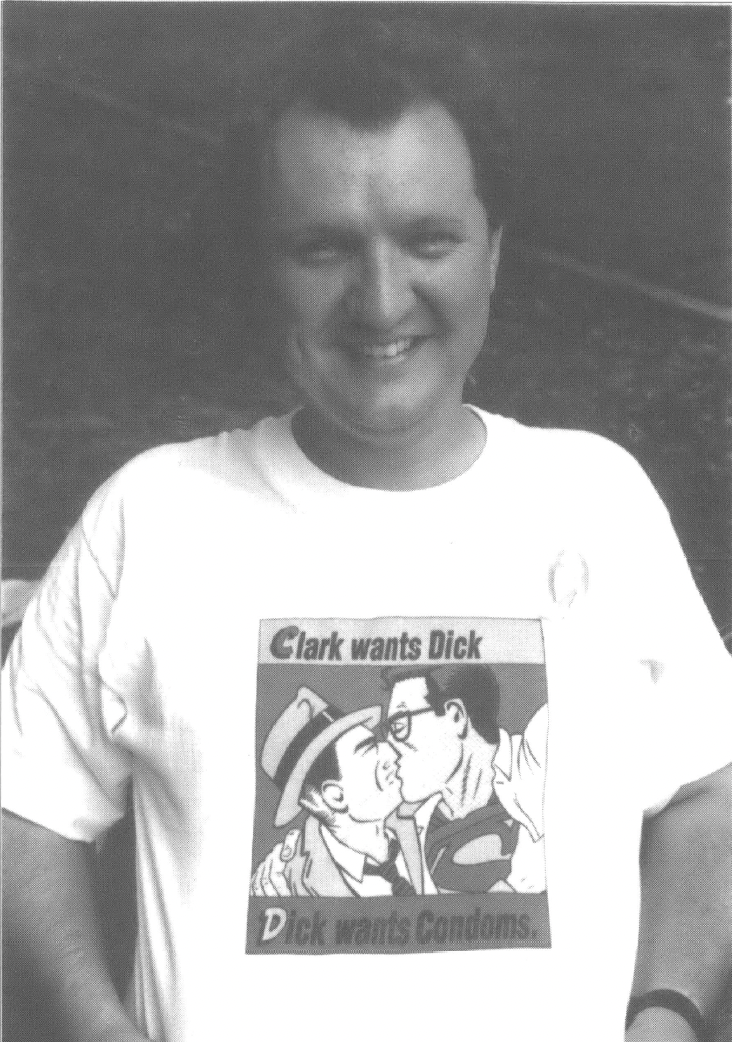

After graduate school, my journey continued with my work as the executive director of the North Carolina Lesbian and Gay Health Project. Being the head of this small community-based organization gave me a unique and sometimes terrifying vantage point. In my first week of work, state government hearings took up anonymous HIV testing. Should it continue in North Carolina or should names be given to state officials? While testifying against anonymous HIV testing, Dr. Paul Cameron, a psychologist, advocated a quarantine of those with HIV/AIDS under the guise of sound public health. I felt the hatred this man had for those with HIV, not to mention his attitudes towards gay men. It reminded me of the Baptist church and the hatred towards homosexuals.

Growing up in an intolerant church, I thought I had become numb to the effects of the intolerance and hatred. But the work I was doing tested my fortitude constantly. While teaching medical students about lesbian and gay issues and providing AIDS education in work places, I heard snickers and moral judgments about how wrong it was to be a homosexual.

These interactions exacted an emotional toll. Bigotry and hate stripped away my self-esteem. Because LGHP was the only organization in North Carolina devoted to lesbian and gay issues, I was not only out, but I was a “professional queer,” and I needed to learn to deal with homophobia and its manifestations. It was a hard and lonely spot.

I learned to cope with overt homophobia without denial or emotional numbing. Often this meant getting in touch with my emotional wounds, feeling them, and healing them. After the hearings on anonymous testing, I went home, sat in the middle of my bed, felt the hatred and hurt, and cried. At first, this process was difficult for me. I was self-critical and oftentimes felt incompetent. Yet, the next day I would face workers at Duke Power or medical students at the University of North Carolina.

A strong supportive community is necessary to fight bigotry and hatred. I trusted lesbians and gay men. I believed I did not need to protect myself from homophobia among them; I did not need my armor. But I soon found many gay AIDS leaders who wanted to disassociate themselves from the gay community and a gay identity. Several argued that funders, particularly individuals, would not give money to gay men and lesbians. As AIDS became more accepted in the mainstream, they told me we should move away from a lesbian and gay identity.

A fairly prominent gay man came to a board committee meeting to discuss whether he was interested in being on the board. I was unprepared for his comments. He suggested that the only circumstances under which he would join the board of directors would be if the organization changed its name. He argued that “the organization would never become mainstream as long as it had a name reminiscent of the radical ’60s.” He defended his position by discussing how “out” he was to his family and at his workplace and argued that there were many in the community who felt the same.

I was confused. I felt, once again, like I had sat through a sermon in the Baptist church. I couldn’t help thinking to myself, “Homosexuals are worthless, sin-filled, and damned to hell.”

Until I came to recognize this man’s homophobia, I had this naive conception that “out” gay men and lesbians understood the power dynamics of a patriarchal society. Now that I was out myself, I couldn’t imagine gay people assimilating and compromising their identity for individual power. I thought they understood that to attempt to fit the mold of the powerful (Christian, straight, white man) meant moving away from those who do not fit that mold. But as I became closer to the gay community, I found at its core the same oppression and repression that I had known growing up.

The gay community carried its own unspoken definition of a “good gay man” and the “bad gay man.” Everyone understood. The good gay man was not effeminate. He did not take a political stance. He never questioned the prevailing power structure or its authority. He never talked about sex, or if he did, it was clouded with conquest or criticism. He condemned any association with lesbians, and sometimes even protested using the words “lesbian” and “gay,” opting to ignore his identification with other individuals. He had a sculpted chest and moussed hair. He declared that being gay should not be and is not a big deal to him. The bad gay man was everybody else.

Take a look at personal ads that say, “Seeking good looking, straight-acting male for friendship, maybe more. No fats or femmes.” Listen to conversations where men relegate women to “fish,” and any gay man above 50 is an “old troll.” Overhear a white man talk about the “monkeys” in the bar tonight. Watch the attractive men at the bar, the number of men who approach them, the glowing response to someone attractive and the snub of the less attractive. Compare the number of gay men who participate in local politics or volunteer with local community organizations with the number of men at the bar on Friday night.

These behaviors are mirrors of our dominant culture, but I had hoped — believed — that gay men would be immune. But why should I be surprised when I saw such characteristics of our culture?

I gained a sense that this rampant and destructive internalized homophobia, coupled with racism and sexism, separates gay men from communities of color, women, cross-dressers, people with disabilities, old gay men, and young gay men. It creates a community unable to open up to the differences that exist within the community. It builds walls, walls that protect but also isolate. I caught glimpses of myself mirrored in the men in this community. I see the same confinement I felt in the three-foot by three-foot cubicle. I see an emotional impotence—an inability to build connections.

Add HIV. I don’t want to make things more complicated, but HIV is part of all our lives, especially gay men’s. The first time I learned about AIDS, it was a Sunday morning. I was sitting on the floor of my parents’ living room, and I was reading the local newspaper. It was the summer after my high school graduation. The Associated Press had a story about five gay men in the Los Angeles area who had died of pneumocystis pneumonia. I remember thinking, “This will touch me at some point in my life.” I was 18.

Eight years later, after many emotionally detached sexual partners, after working in a hospital with persons living with HIV, after acknowledging my gay identity, I had come face to face with the effect HIV had on my life. I struggled with the new walls created by this virus. I have heard gay men say it is scary being a single gay man. It is scary to build relationships with other gay men because you don’t know who will live and who will die. I don’t know if I will live or die. I am afraid to connect, afraid to lose, afraid to hurt, afraid of being alone —-again. I know that loss will be a part of my life. Given the new data about gay men suggesting that between the ages of 20 and 50, there is a 50 percent chance of HIV infection, being alone seems like an unavoidable reality and disconnectedness, a repetitive theme in my life.

Which creates so many questions. How do I make and maintain connections? How do I connect the spiritual, sexual, emotional, and political pieces of my life? How do I overcome the fact that disconnectedness has been key to my survival? How can I make my actions and beliefs match? How do I help create and sustain the world I need for this work? How do I connect with other friends, sexual partners and lovers, while maintaining the integrity of my own connections? How do I make new connections with drag queens, African Americans, poor people, and anyone who seems to be different?

Fear and Power

Connecting the pieces of my life and my life with others requires first being truthful in all my relationships and removing masks I still hide behind. With a network of friends and support for my personal work, I can deal with the fear about what lies behind my masks. And I can also deal with the ostracism I feel as I mirror places of pain in other gay men.

In my next step toward achieving connectedness between the parts of my life, I examine the events that shattered my self-esteem. I remember the messages from church and family that created a sense of worthlessness. I remember boys on the playground calling me “sissy” when I chose to jump rope rather than play baseball.

Their name-calling has made me more attuned to the effects of the snickers and catcalls when I am the “professional queer.” Somehow, and I’m not certain how, by opening, acknowledging, and allowing the pain and fear of these events to enter into my life, they lose their power, and I’m able to become more confident and self-assured.

Witches have a saying, “Where there is fear, there is power.” In my own life, I am increasingly amazed at how the things that frighten me can create joy and compassion. The fear of losing a friend to HIV/AIDS makes me recognize the importance of our time together and creates a powerful bond. Speaking from my heart at a public meeting is frightening but can liberate and transform me and have an impact on public policy. Telling my personal struggle to a seemingly hostile audience is frightening, but often I am met with empathy and compassion.

Spiritual forces are at work in my life. They are helping me recognize power that moves me beyond fear and pain. These forces are no longer tied to any formal religion, but rather give me a clear sense that everything is connected and valuable. No one judges my goodness or badness — not even God. However, the actions I choose have consequences for me, my relationships, and the world. Those consequences and a sense of integrity are beginning to serve as the basis for my sense of my own value.

In her book, Dreaming the Dark, Starhawk, a witch, activist, feminist, and author, expresses the vision in which there is no split between the spiritual and the political, and the dualities created by our culture lose their power. Individual integrity and relationships serve as the foundation for justice.

Integrity for myself centers on the value I hold for myself and my sexuality. Imagine what it might have been like for me if sex were considered sacred, beautiful, cherished, and above all respected, and if communication about sex were considered comparable to the importance of God and the church. I would never have felt fear, shame, or isolation. Instead, I would have been loved, embraced, and supported by my family and community while exploring my feelings about my sexual identity without acting on them in risky ways.

Through my work and its connection to other social justice organizations, I am awed by the personal power created by the community building that comes out of community organizing. In my new role as development director of the Piedmont Peace Project, I watch low-income communities and communities of color take leadership roles and challenge traditional white, male power structures.

I see stories of oppression similar to my own. The recently produced film, “The Uprising of 1934,” examines union organizing in textile mills throughout the South and the widespread 1934 textile strike. I felt pieces of my own story as I heard about the union organizers being blackballed and ostracized. I could feel the pain of the workers as they were teased and called “lint heads.” It was here that I realized work in the lesbian and gay community cannot occur in isolation.

I have a lot to learn from these folks. They can share their community organizing strategies and teach me how to cope when it seems so hopeless. I can share, in my own way, the pain I have felt by being a member of another oppressed group and how I cope with loss throughout my life. Most importantly, I begin to look at my own self and my integrity. I feel we can provide the mutual support necessary to challenge those who create oppressive systems.

Tags

Stan Holt

Before joining the Piedmont Peace Project, the organization that edited the special section in this issue, Stan Holt was development director for the Institute for Southern Studies, which publishes Southern Exposure. (1996)