This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

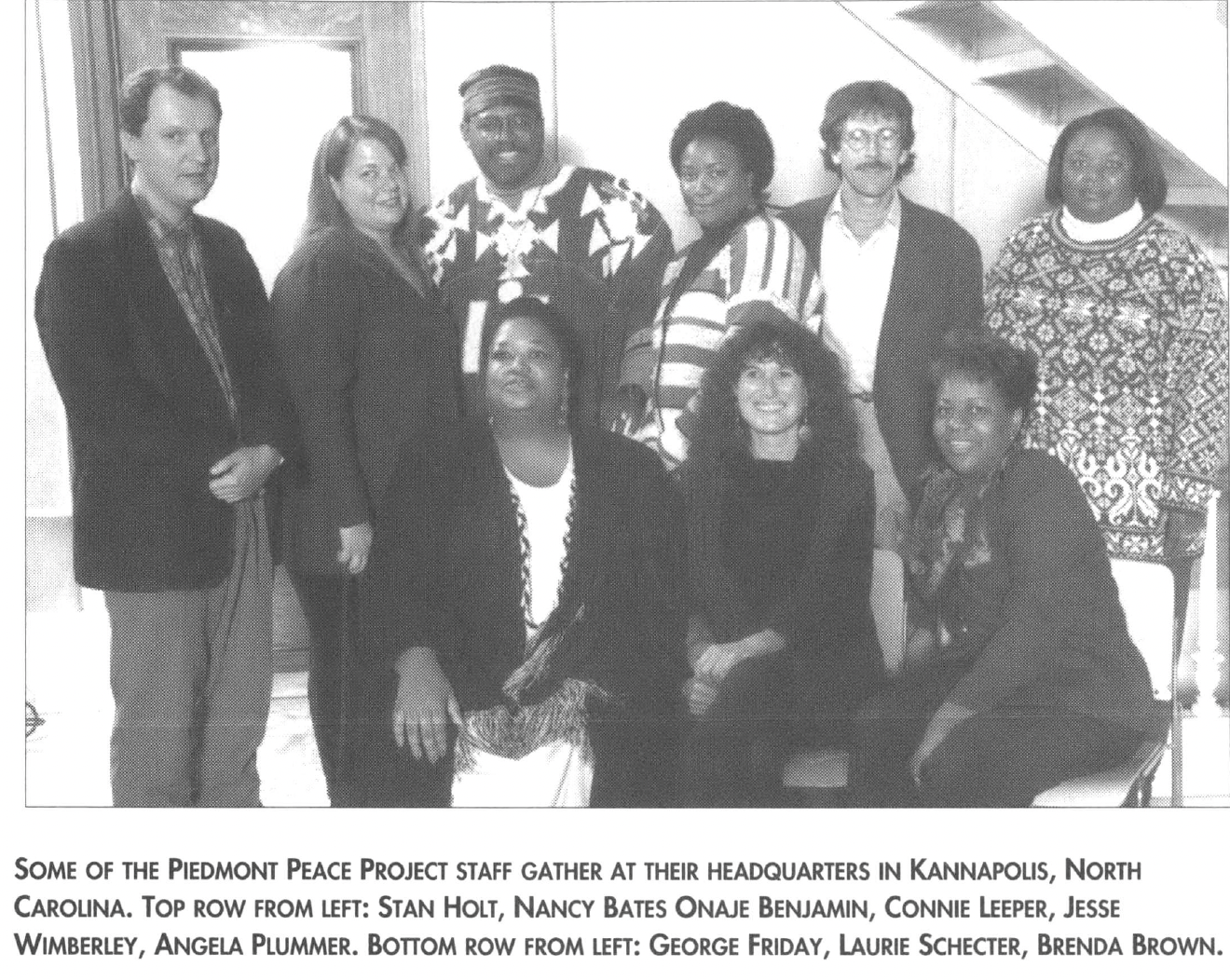

In 1985, Linda Stout, a native of the Piedmont region of North Carolina, and currently director of the Peace Development Fund, founded the Piedmont Peace Project. At the time, no organization existed in the area that brought black and white low-income people together for progressive change. It was PPP’s perspective that outside organizers — primarily white, college-educated, and middle class — could not create such an organization. It would have to be the unique creation of local people who knew race and class issues from their own life experience.

Ten years later, PPP is a potent political force in the Piedmont and Sandhills region of North Carolina. Working together, PPP members have brought home more than $2 million in community development block grants, and they have registered more than 15,000 voters. Through these efforts, hundreds of once-silent people have found their voices and entered into a dialogue with other constituencies in the community — and on the national scene — to work toward constructive political change. The “Finding Our Voices” model PPP developed led to a national training program that is now helping other low-income Southern communities to empower themselves.

Members of the Piedmont Peace Project who are interviewed:

Connie Leeper is a single parent, activist, and lifelong resident of Kannapolis, North Carolina. An African American, she is the daughter of textile mill workers and has been an organizer with the Piedmont Peace Project since 1990.

Onaje Benjamin, a trainer/organizer with PPP, is the son of a factory worker and a food service worker. An African American who grew up in New York’s Harlem, he has been incarcerated various times. He became an activist and community organizer in social justice movements and is now a nationally recognized trainer and counselor for men and youth in the areas of anti-oppression and anti-sexism.

Brenda Brown is a lifelong resident of Jackson Hamlet in Moore County, North Carolina (one of the sites Piedmont Peace Project has helped revitalize with community organizing and block grants). A church and community activist, Brown has been a PPP organizer for a year. She is African American.

George Friday was born in Gastonia, North Carolina, not far from PPP headquarters. The daughter of a truck driver and a schoolteacher, she has worked as a yoga teacher and as a fundraiser for Sane Freeze. She is a nationally recognized trainer in the anti-racism and community development fields. An African American, she has been a trainer and consultant with PPP since 1990.

Southern Exposure: What is the Piedmont Peace Project? How do you define your mission?

Brenda Brown: We are an organization of people committed to changing conditions in our communities. PPP has a staff of six, and about 500 other folks who work with us around the 8th Congressional District of North Carolina. This is a huge area about the size of Massachusetts. We are mainly textile mill and other types of factory workers. PPP helps low-income people develop the self-esteem and political skills necessary to improve their neighborhoods — according to their own vision of community.

S.E: Is your work strictly limited to North Carolina?

George Friday: No. We have a national training program. It’s made up of two different programs — one called Finding Our Voices, for low-income political activists like ourselves, and the other, Building Bridges, for people from privileged backgrounds. Both of these programs are based on organizing principles we’ve developed and used with a lot of success locally.

S.E. What goes on in Finding Our Voices training?

George Friday: The program is designed to overcome “internalized oppression,” a condition oppressed people often end up with after a lifetime of absorbing society’s negative messages. Somehow you’re not as good, as smart, as worthy as others. Internalized oppression usually makes low-income folks, women, and people of color doubt themselves and give up their power. We challenge the stereotypes and teach people to value their own history, culture, and personal strengths. We suggest non-traditional, shared leadership styles. Ultimately, we help identify political issues, goals, and strategies for improving each community we work with. All this takes a series of on-site visits and workshops over a three-year period.

S.E. How about Building Bridges?

Brenda Brown: Building Bridges takes a three-year commitment, too. It reaches out to folks with advantages based on skin color, economics, gender, or sexual preference — people already involved in social change. We help participants understand privileges many of them never knew they had — and how their privileges are manipulated to keep us apart. We explain how privilege can be used in positive ways to make institutional changes.

S.E. Can you give us an example of that?

George Friday: Say you are a white male professor with tenure: You could get yourself appointed to a key university hiring committee. You could make sure justice was done there. Another point I’d like to add about Building Bridges groups. Most of them are paired with Finding Our Voices groups — even though the workshops are mainly separate. Building Bridges groups form these relationships to put new learning into practice. The goal of Building Bridges and Finding Our Voices are exactly the same — to build community across race, class, and other lines that keep us divided.

Brenda Brown: Our vision is not to mute anyone’s voice — not middle-class white people, not black men, not anyone. We’re all in this together. We can’t make major changes alone.

S.E. You say that much of the work is based on successes at home in North Carolina. Can you give us an example?

Connie Leeper: Since the very beginning of PPP 10 years ago, we have always had strong financial support from affluent white people in the Boston area. Even though it doesn’t fit our organizing model to have outsiders organize in our neighborhoods, we see the Boston folks as an important part of the PPP community — necessary to make our organizing possible and to create change on the national level. We wanted our Boston supporters to understand exactly what goes on here. If they had a chance to come down and meet our members, we figured they would get even more connected.

Spring Tour, as we came to call it, was one of our first community-building strategies with our donors. Each year about a dozen people come for a long weekend, and we bring them into our neighborhood to see the way things are. They attend community events, church services, and afterward we treat them to a country breakfast of ham and grits.

What we didn’t anticipate was how hard all this could be on us. For instance, one of our staff members was riding with a group that pulled up to an event in one of our communities. One woman said, “Should we lock all the doors?” Later there were comments about our food — too greasy; how come everything has to be seasoned with pork?

Early on we tried to do a formal workshop at the end of the weekend looking at barriers between us — but the visitors got too defensive. Finally we changed to more of a coffee-hour type informal discussion. We asked each person (including staff attending the meeting) to write down the five stepping stones in their lives that got them to Spring Tour. Then we invited people to identify the barriers in their own lives that prevent them from doing social change work.

We lost one person after a weekend like this, but in general, Spring Tour has worked, and the benefits have gone both ways.

George Friday: One of the lessons we learned from Spring Tour is that people from the same background need separate, safe spaces where new learning can take place. In Building Bridges Workshops, we have heard stories of deep personal pain from people who grew up in wealthy families. We acknowledge those hurts, and we also help people see that their pain is different from systematic oppression backed by institutions. When folks have a chance to deeply examine how both privilege and internalized oppression work, they can meet people different from themselves on common ground. As it stands now, a good number of our Boston donors have gone through Building Bridges programs we organized in Massachusetts.

Onaje Benjamin: After people have had time to work in a safe space, then we can bring everyone together for a dialogue. But not until that point. Which brings up the example of our gender work. We started with a few focus groups, for lack of a better word, to set the stage. One was a group of about 16 African-American men from ages 30 to 70. The other was a group of African-American men below 35. We said to each group, “It appears that women are at the forefront of social change in this region. Where are the men? What are some of the barriers that prevent you from working together as equals with your partners? What is difficult about being an African-American male in the South?” We kicked all this around; then basically listened to what they said.

The older men reflected a lot on their grandmothers, how much they had done and still did. There was a lot of emotion. They talked about their distance from their own fathers and how fragile the economic status of African-American men in the South was, how shut down they had to be at the workplace, and how they had to mask their anger there. With the younger men, their armor was much more up. Their language was very sexist. At one of the meetings with the older men, a guy backed away from me a little. Later he told me he thought I was going to hug him. I decided to take a shot that night and get men thinking. I wanted to explain that fear of each other — it’s homophobia — is part of the oppression that keeps men from working together. At the end of the session, the guy who moved away from me said, “What the heck!” and he hugged me. We all hugged each other. Then he said, “I have to go home and hug my son.”

The gender work is about moving men into a place where they can enter a partnership with women to do social change. But first we have to move men to a point where they can see their own shadow.

Connie Leeper: We are working on the women’s part of the gender issue, too. We started a women’s group that includes both low- and middle-income members.

Onaje Benjamin: Before you get to the goal of partnership, you have to start building trust across the genders. Ideally, about six months after a men’s group and a women’s group begin, you bring the two groups together for something very safe — like a dinner and a discussion about gender roles and how they’re played out in society. Maybe the women would talk and the men would just listen.

S.E. Back to Building Bridges for a moment. Tell us more about what you do with affluent activists — “people of privilege” as you call them.

George Friday: Well, remember our work takes place over a period of three years. And unlike the informal ways that work for Spring Tour, we have a formal curriculum. It includes discussion, a lot of interactive exercises, some formal lecture, and a list of books and articles to read. We spend time examining racism, and how it is far more than personal prejudice — it’s prejudice with institutions behind it to keep it in place.

S.E. Can you point to any concrete success in the Building Bridges program?

Brenda Brown: I’ll give you a recent example. This December, we had a huge 10th year anniversary celebration for PPP in Boston. There were several activities including a dinner dance for about 200 donors. We sent 26 from North Carolina including staff and members. All of us stayed at the home of donors — just about all of them had been through Spring Tours and Building Bridges programs.

Once I was very reluctant to stay at a donor’s house when I did fundraising in Boston. I went way out of my way to stay with relatives. For me, the trust was not there. This time, things were really different. The hostess gave us the keys — two black women and a black man she barely knew. We spent a lot of time with her. We even laughed openly about the differences between a Boston breakfast — fruit cup and a piece of toast — and our grits, ham, and eggs.

At the dinner dance, all of us from PPP were able to relax and cut up. We felt trusted; we didn’t have to live up to anyone’s expectations. There’s sure no better way to build community than to let people be themselves.

Tags

Laurie Schecter

Laurie Schecter, Training Program Coordinator, was a member of the PPP donor community in Boston before joining the staff as a full-time volunteer. (1996)