The Business of Anti-Racism

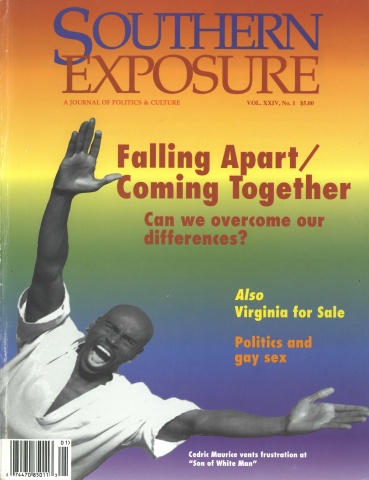

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

The training session takes place in a large meeting room at a local hotel. Before the event starts, white employees laugh nervously as they fill their coffee cups or steal out for a quick smoke. In this group of 40, a small clutch of three black employees stands in the back of the room talking quietly, while the single Latina and Asian employees take seats next to each other at the end of the second semi-circle of 10 seats.

Confident and smiling in stylish suits, two women, one black and one white, call the session to order. The day-long training in “Unlearning Racism” begins promptly at 9:10 a.m. Joan Doads, a white eligibility worker with the Department of Social Services, is a participant in the training session. She does not consider herself a racist, although she is honest enough to admit that after years of front-line work in the welfare department, she does carry some stereotypes about women on welfare.

She is actually surprised by the training. One of the sessions allows her to compare her feeling of being excluded when she moved to the city from a small town in eastern Kentucky to the exclusion people of color feel all the time. The session is quite moving for her emotionally. She is also impressed with the delineation of the dimensions of “white privilege” and the brief exercise that explores the web of institutional relations which promote racism. While there are some exercises Joan thought were hokey, overall, she is impressed with the training and leaves it resolved to do what she can to “interrupt racism.”

The following week Doads is back at her job at the welfare department. Despite her resolve about interrupting racism, she can still only offer her black or Latina clients limited job access, even more limited training or educational opportunities, and few support services to do either. Her job reinforces the racial order.

Has Doads’ training done much to address racism? Variations of this scene are repeated every day all over the country. Training session participants are exposed to the history of racial (and in some cases, gender-based) discrimination, given tools to understand their personal relationship to the perpetuation of racism, and, at times, taught how to “interrupt racism.”

The Race Relations Industry

Anti-racist, or the broader-scoped “diversity” training, has become big business. While this new demand for training may be motivated in part by a sincere interest in addressing issues of race and gender discrimination, the dominant motivation is to make the workplace continue to function smoothly despite its changing demographics, especially at the corporate level. Studies published in the late 1980s and early 1990s found that over half of the current U.S. workforce is composed of women and people of color, and projected that white males would make up less than 15 percent of those entering the workforce over the next decade.

Dozens of firms have sprung up to meet the new demand for “managing diversity,” while relatively stodgy middle-of-the-road organizational development firms have added a “diversity” track to their repertoire, charging corporations and large nonprofits from $300 to as much as $8,000 a day for a single trainer.

The training is heavily marketed, with vast differences between the community-based “anti-oppression” trainers and the more corporate “diversity managers.” “The issue of cultural diversity,” observes San Francisco State Social Work Professor Margo Okazawa-Ray, “has created a race relations industry wherein anyone with a modicum of interest, creativity, and academic credentials can conduct workshops ostensibly to improve race relations.”

But do these sessions actually improve race relations? Aside from the criticisms of dyed-in-the wool racists who generally find the sessions an unnecessary annoyance, there are three major criticisms of the training sessions. The first is that they tend to reduce racism to individual attitudes and acts of discrimination. This obscures the fact that institutional racism, the system of racial inequity that exists in a wide range of institutions by the normal process of their operation, is not dependent on the intentions of individuals. The second is that the training sessions are essentially commodities, slick packages which appear to provide an instant cure for a complex social problem, masquerading as social justice activity. The third is that “diversity training” in particular has, as its major goal, neither power sharing nor an end to discrimination, but rather, according to Ray Friedman of the Harvard Business School, “the creation of a work atmosphere where productivity will be highest.”

Can the same training sessions geared to produce the corporate goal of increased productivity also achieve the radically different objective of some nonprofits — to shift power relations within the institution, and ultimately within society itself? Probably not. However, much of the training material shares a common source, White Awareness: A Handbook for Anti-Racism Training, a 1978 model for prejudice reduction developed by former University Professor Judith Katz, and published by the University of Oklahoma Press.

Katz’s work was adapted by many early trainers, some of whom changed the order of the sessions, believing that it was important to reach people at an emotional level earlier than Katz projected. Others, in particular the New Orleans-based People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond, added strong historical components documenting the history of U.S. racism and an easily accessible “foot analysis” which, according to one participant, “gives people a real understanding of who’s kicking you in the butt.”

Current training models include a wide variety of training formats and styles. Some focus only on race, while others address all forms of oppression. Some focus on organizational direct action while others focus on interpersonal relations. Some of the training formats are directed at individuals with no organizational affiliation, while others are only geared to address organizational dynamics.

As with any other endeavor which attempts to address attitudes, the effectiveness of the training is as dependent on the receptivity of the individual or organization as it is on the skill of the trainer and appropriateness of the design. Therefore, while it is difficult to assess the general results of anti-racist training, it is possible to examine the effects of some specific efforts.

Making the Personal Political

Stridently addressing the criticism that anti-racist training does not address institutional change, veteran civil rights activist C.T. Vivian, CEO of the Atlanta-based Basic Action Strategies and Information Center (BASIC), argues, “You’ve got to start with the personal. People are often so personally prejudiced, they don’t really care about anybody’s humanity, including their own. You have to force people to drop their defenses. You have to wedge them loose from them and help them to care. When people care, they become creative.”

There is significant evidence that Vivian’s efforts to “make the personal political” have borne fruit. Dr. Lawrence Clark, Associate Provost for Academic Affairs at North Carolina State University, points to concrete changes at the University which are direct results of Vivian’s work. “C.T. has conducted three to four seminars every year since 1975, reaching over 1,300 people.”

Clark, who remembers meeting Vivian in 1963 when Vivian came to his hometown in Virginia as a civil rights worker, observed with a chuckle, “His tactics are confrontational, and once you get into the seminar, there’s nowhere to hide. But prior to C.T.’s intervention, we had very few black students in the textile, agriculture, and forestry departments. As a direct result of his work, we’ve not only managed to significantly increase black enrollment in those departments, we’ve hired African-American outreach and retention coordinators for each unit and created pre-college science and mathematics programs starting in the middle schools.” He added, “The seminars are not a panacea, but they were very helpful.”

Percolating and Slow Dripping

BASIC’s initial audience was strategically chosen, starting with deans of the college and continuing with department heads and finally faculty and students. Getting the support of key decision makers is an important dimension of the work. “It’s people in positions of power and authority that have the power to make change,” says Sister Gudalupe Guajardo, an anti-oppression trainer with the Oregon-based group, “Tools for Diversity.”

Guajardo’s experience includes addressing the prejudicial attitudes and actions of the Portland police, working with students and faculty to alleviate racial tensions on college campuses, and addressing issues of racial and gender discrimination within religious institutions. Aside from the importance of getting key leaders on board early, Guajardo points to another important factor in successfully addressing institutional change: “We develop a task force of people inside the organization to continue the work.” Making organizational change is a combination of what we call the ‘percolator and slow-drip’ methods. Whether the training focuses on personal awareness or we conduct an organizational assessment of race/gender discrimination patterns, it tends to percolate or stir things up. However, in order to make the change, we often have to support the ‘slow drip’ to overcome the inevitable institutional barriers to change.”

Anti-Racism at the Community Level

Unlike larger institutional settings which tend to be highly structured and hierarchical, conducting anti-racist training sessions with community-based organizations can pose a different set of challenges and achieve different results. For example, Shirley Strong, manager of the Levi Strauss Foundation’s Project Change, works with an explicitly antiracist initiative. She has worked with prejudice reduction trainers from both the People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond and the National Coalition Building Institute in the foundation’s community-based programs. Strong observes, “The training gets people talking the same language and helps frame the work. People get to understand and accept the concept of white privilege and racial oppression on an emotional, experiential, and intellectual level.”

She is also convinced that the training can provide a framework for action: “When the Klan proposed a march in Valdosta, Georgia, it was community residents that had been through the training session that successfully mobilized community opposition. The Klan decided not to march. I think that’s pretty significant.”

Not all efforts to address issues of race at the community level have been completely successful. James Williams, an organizer with Grassroots Leadership, a regional organization based in North and South Carolina, observes, “Although we have made some progress in addressing issues of race, gender, and homophobia, we are still experimenting with the most effective type of intervention.” Williams coordinates the Barriers and Bridges Project, a multi-state effort to address difficult issues of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation within organizations. He noted that some groups like the North Carolina chapter of NARAL (National Abortion Rights Action League) and the Self-Help Credit Union in Durham used the training to create more leadership opportunities for African- American women. For some other organizations the training created internal problems.

“One problem,” observed Williams, “was actually related to too much enthusiasm. Each group participating in the Barriers and Bridges project has a two-person bi-racial team to address issues of personal prejudice and institutional racism and to analyze the structure, culture, issue priorities, and power dynamics within their organization. Sometimes team members exposed to the training would recognize clear inequities in their organizations and would attempt to ‘fix’ them without first helping everybody else to see them. Obviously this caused tension.”

Another level of the problem, he said, “is that when some groups are confronted with the contradictions of their own practice, they are really not prepared to change.” The important assumption by organizers of the Barriers and Bridges project, that basic change in the arena of race relations must come at the community level and should be modeled by community organizations, is shared by the Southern Empowerment Project (SEP), a 10-year-old multiracial association of eight community groups based in Marysville, Tennessee. A fundamental part of SEP’s mission is to solve community problems by challenging racism and social injustice.

The organization’s approach to challenging racism has included a combination of anti-racism workshops, facilitated discussion of how racism affects the organizing approaches and agendas of member groups, and the development of SEP’s own institutional initiatives to increase the number of, and support for, African-American leaders and organizers. There has been some backlash to SEP’s focus on racism in its annual organizer training program, especially from some of the younger, white, college-educated interns who feel that the organization’s training is too hard on whites.

But overall, in the words of SEP coordinator June Rostan, “the effort to get serious about racism has had positive results.” Reflecting on an SEP training session that local leaders from her organization attended several years ago, Maureen O’Connell, veteran organizer and staff director of Save Our Cumberland Mountains (SOCM), an organization with a predominately white membership in east Tennessee, said “This was the first training of this type that leaders from SOCM had been to. It was very helpful that the structure was organizational and not just individual, so it addressed why it is in our self-interest for the organization to cross racial barriers and be involved in this work. The discussion gave me real insight in ways to talk about members’ self-interest in addressing issues of race.”

SEP also assisted SOCM to develop an ongoing relationship with JONAH, a west Tennessee organization with a predominately African-American membership. This multi-racial cross-organizational alliance includes joint leadership training and legislative advocacy (See “Profiles in Cooperation”).

Like Williams, Rostan’s assessment of SEP’s progress is modest but hopeful. “We’ve changed some attitudes and we have an excellent opportunity to experiment with and work on institutional change.” Obviously, there are many factors to assess when considering the effectiveness of work in the arena of dismantling racism. Trainers and community activists interviewed on the topic all agreed that long-term evaluations of different approaches would be helpful in improving the work in the field. In the final analysis, the only real measure of success of anti-racist work is concrete changes in conditions for people of color in the United States.

Applied Research Center

25 Embarcardo Cove

Oakland, CA 94606

(510)534-1769

Barriers and Bridges Grassroot Leadership

PO Box 36006

Charlotte, NC 28236

(704) 332-3090

BASIC (Black Action Strategies & Information Center)

595 Parsons Street

Atlanta, GA 30314

(404) 688-5935

Levi Strauss Foundation Project Change

1155 Battery St.

San Francisco, CA 94111

(415)544-7420

National Coalition Building Institute

1835 K Street NW, Suite 715

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 785-9400

Technical Assistance for Community Services

1903 SE Ankeny

Portland, OR 97214

(503) 239-4001

Before You Train

The Applied Research Center has developed the following list of criteria for assessing the approaches of trainers conducting antiracist work. While our criteria for assessment do not ignore the subjective questions of how people feel about themselves and others, it places greater emphasis on the degree to which organizational activities move people towards the goal of racial equality:

1. Does the activity truly address the complexity of the racial spectrum? Most of the exercises, examples, and modes of analysis used by current anti-racist groups only address the limited spectrum of black/white relations. Given the subtlety and complexity of U.S. society, this approach not only fails to address the relationships of other people of color to whites, it misses a major dimension of racial conflict by ignoring conflicts among people of color. In order for anti-racist work to be effective, it must include methodologies to address the power relationships between whites and people of color and among different groupings of people of color.

2. Does the activity develop the capacity of people of color to address their own oppression, or does it simply emphasize the ability of whites to become noblesse oblige allies?

3. Does the approach include an action plan reflecting changes in behavior? “Where the feet go, the head will follow” is an old axiom in community organizing. This axiom is based on a theory of learning by doing and on the common sense notion that it is much easier for people to repeat behavioral changes if you’ve planned it and helped people through the first time.

4. Does the approach lead to direct policy changes? Changes in policy can reinforce or even mandate changes in behavior.

5. Is there an evaluation component which addresses both individual progress in prejudice reduction as well as progress in institutional reform?

6. In an organizational setting, are the activities appropriate to the organization’s stage of development, the political context, and the level of interest of key institutional actors?

7. Are the activities of the approach connected to other parts of the anti-racist movement and to a more general social justice agenda? In order for people to participate in sustained action, it is necessary to see their specific anti-racist activities connected both to other parts of the anti-racist movement, and to the larger movement for social justice which addresses issues of race, sex, class, sexual orientation, social ecology, and economic equity.

8. Do the activities assist participants in developing an analysis of the way racism works and how it complements the other oppressive “isms” in society?

9. Does the approach of the training organization, in all of its activities, model relationships which do not reinforce the dominant “isms”?

10. Does the approach develop the capacity of organizations of people of color to effect change in the society?

Tags

Gary Delgado

Gary Delgado is the Director of the Applied Research Center in Oakland, California. (1996)

Gary Delgado is director of the Center for Third World Organizing. This article is reprinted from Third Force, the newsletter of the Center for Third World Organizing. (1984)