This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

I am a 37-year-old white man, low-income, the father of four children. I live on a small farm in rural North Carolina with my wife and kids. We live in the home my great-grandparents built when they arrived here in a covered wagon 125 years ago. Like many of my neighbors and cousins, I cannot support my family from the land the way our ancestors did. I have been unusually lucky to hang on to my family property and escape work at the local hosiery mill. Instead I travel around the county as an organizer, helping low-income people develop political skills. Black neighborhoods in Moore County are often receptive to social change, and welcome progressive ideas. But in white working class neighborhoods like my own, the “communist” notions of community organizing are not yet welcome — even from a native son.

Last spring, my wife and I took a walk near our farm. We came upon my cousin Bob and five other neighbors in a pickup truck. Although I didn’t know it, they had just finished planting a nearby field with watermelons. I said hello and asked what they were doing.

“Waiting for the law,” Bob said.

“Why?” I asked “For baiting coons,” he said. The rest of them giggled.

It took me a minute, but soon I understood. It’s illegal to plant food expressly to bait wild animals. And black people, so local white people say, are crazy about watermelons.

“O.K.,” I said. And I thought to myself, “There’s a lot of work to be done.”

The exchange was typical of how my neighbors and cousins in rural Moore County greet each other. Verbal connection is made with racist, sexist, or homophobic references that are meant to be humorous. Community in our area is often built upon an acknowledgment of what we stand against. Not only are we against equality with blacks, we are against Mexicans, homosexuals, and abortion.

Community for us has also been built on an understanding of the place of neighbors who, out of necessity, came round several times a year to help harvest the crops, shuck corn, and slaughter pigs. Until the end of the Great Depression and the beginning of World War II, mutual economic dependence was the cornerstone around which good times could grow. Shared work whetted everyone’s appetite for food, drink, gossip, and square dancing once the sun went down.

The loss of independent farm culture rocked us out of our place in the universe. We — particularly the men — looked for someone outside of ourselves to blame for the frustration and anger. Using the racism, sexism, and homophobia that already existed in the community we found convenient scapegoats.

My cousin Bob and his wife are examples of what has happened over the years to white working-class people in our area. Bob and Hilda live in a trailer. They own no land, and both of them work in the hosiery factory. This summer when Bob and I grew watermelons together on my farm, we talked about how life used to be and how someday we’d buy a tractor between us. This would help Bob realize his dream, which he described to me practically in tears — his own land, enough soil to grow food for his family, and an end to the job at the hosiery factory.

That dream is way out of reach. Family farms dried up here in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s because government agricultural policies radically changed to support agribusiness. And just as it happened with so many people around the United States, one by one by one, the small family farms vanished. Farmers sought economic refuge in nearby factories. Now that refuge is drying up as well.

The global economy also hit low-income wage earners right between the eyes. Not only are foreigners coming into town, some of our factories are moving. We recently lost 500 jobs when a Proctor Silex plant ran away to Mexico. Without an understanding of GATT and NAFTA, rumors offer locals the only explanations. My cousin Bob believes our economic problems are caused by Jews and other people he does not understand.

That day last summer when Bob and I were planting watermelons, we fantasized about a shared future — a farm big enough to support both our families. “Wouldn’t it be great?” said Bob. “But let’s not hire any Mexicans.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because they’re taking our jobs.” he said.

“Is that right? How is that?” I pressed him. “I don’t know,” he said.

“Do you think maybe that plants are closing in Mexico, and there aren’t any jobs?” I asked. “Or maybe jobs there don’t pay enough for folks to take care of their families, and they come here thinking it’s the land of opportunity? Could it be that it’s not so different from our own ancestors who felt they had to leave Ireland in the 1800s?”

Here was a set of circumstances Bob could understand. The Mexicans were poor, just like him. The company where Bob works had not tried to establish common bonds among the locals and the Mexicans — if anything, the foremen seemed to play on the cultural differences. The idea that guys from a foreign country were pouring in to take over their jobs had created more frustration and anger than ever.

Low-income white men had bought the idea of the American dream: If I am good enough, if I can only work hard enough, I will live in the lap of luxury. If I have not achieved the American dream for myself, why not? How come I’m such a loser? Our religion reinforces these feelings. Christianity tells us we are responsible for the support of our families. If we just scrape by, we’re to blame for our own misery. This kind of thinking creates an overwhelming sense of loss.

Politicians exploit the sense of loss. They provide us an acceptable way to knock someone other than ourselves. We blame the welfare moms. We blame immigrants. The blaming becomes the substance of our greetings; and our greetings become a metaphor for the vacuum we have filled with hate.

I do not try to meet every racial slur that comes my way with a counter statement. Often I register no reaction and move to another subject. Folks who find this politically incorrect are right — it is. But it’s real life for a person who wants to live and make changes in a small community such as mine. What works is a combination of maintaining neighborly relations and seizing the “teachable moment,” as organizers say — like a quiet conversation with my cousin Bob. And in these conversations, I do not challenge Bob’s belief systems. I challenge his information. With this approach, the Bobs of this country can see they have more in common with a Mexican machinist than with a U.S. factory owner.

If progressives — who mostly come from middle- and upper-class homes — want to reach the hundreds of thousands of low-income white men in this country, they must first affirm that pain and loss exists in these communities. (Affirmation should not be mistaken for endorsement or release from responsibility.) Low-income white men, on the other hand, need to know they enjoy some privileges other Americans do not.

For me, getting that far was a challenge. It was hard to admit that despite my desperate economic situation, I was born with some privileges: I’m white, I’m male, I’m straight. For these reasons, I am afforded a certain amount of respect and attention. It is a struggle not to use these unearned privileges to my advantage in relationships with women and people of color.

When a man has so little control of his life, using privilege to keep others down feels mighty good. As long as we keep holding onto our illusions of power, we don’t even look at the larger issues of what’s happening to the economy, for instance, policies that allow runaway corporate profits and declining worker wages, job security, health, and safety conditions. It is the low-income white man who votes for North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms and other southern conservatives who support such policies. These politicians use inflammatory race and gender issues to keep us from recognizing what we have in common with others. We are then unwilling to form coalitions that pressure for sound economic policy. Without those coalitions, the life Bob and I envisioned that warm day last summer is simply impossible.

Here’s a dream that comes to mind: A facilitator of some sort — minister, workshop leader or community organizer — brings a small group of low-income men in my area together. There in a safe space; folks vent their pain, prejudice, and anger. They identify and fully acknowledge a long list of wounds. Over a period of time, the group leader brings the men to see how these open wounds affect interactions with others.

At this point the group is encouraged to take a bold new step — to invite some newcomers to join them for an evening — and actually enjoy their differences. Ultimately the men work together to create a positive and inclusive vision of life in our community.

The group leaders I envision to do this work are men like myself — different, yes, but from low-income backgrounds. Right now we are the only ones who will be trusted in a community such as mine. And without trust, expect no true conversation.

Ultimately, the hopelessness and powerlessness of white, rural low-income men will need to be addressed by society at large. The rage that emanates from communities like mine should be redirected toward the true source of our problems — a corporate system and a government that doesn’t care about our problems. This is not just my selfish wish — one man desperately seeking to overhaul one isolated rural community. If progressive politics are to succeed in the United States, we will need vast numbers of us from all walks of life. That means my family and neighbors, too.

Before they can be reached, there’s a long bridge to cross — and it’s not yet built.

Tags

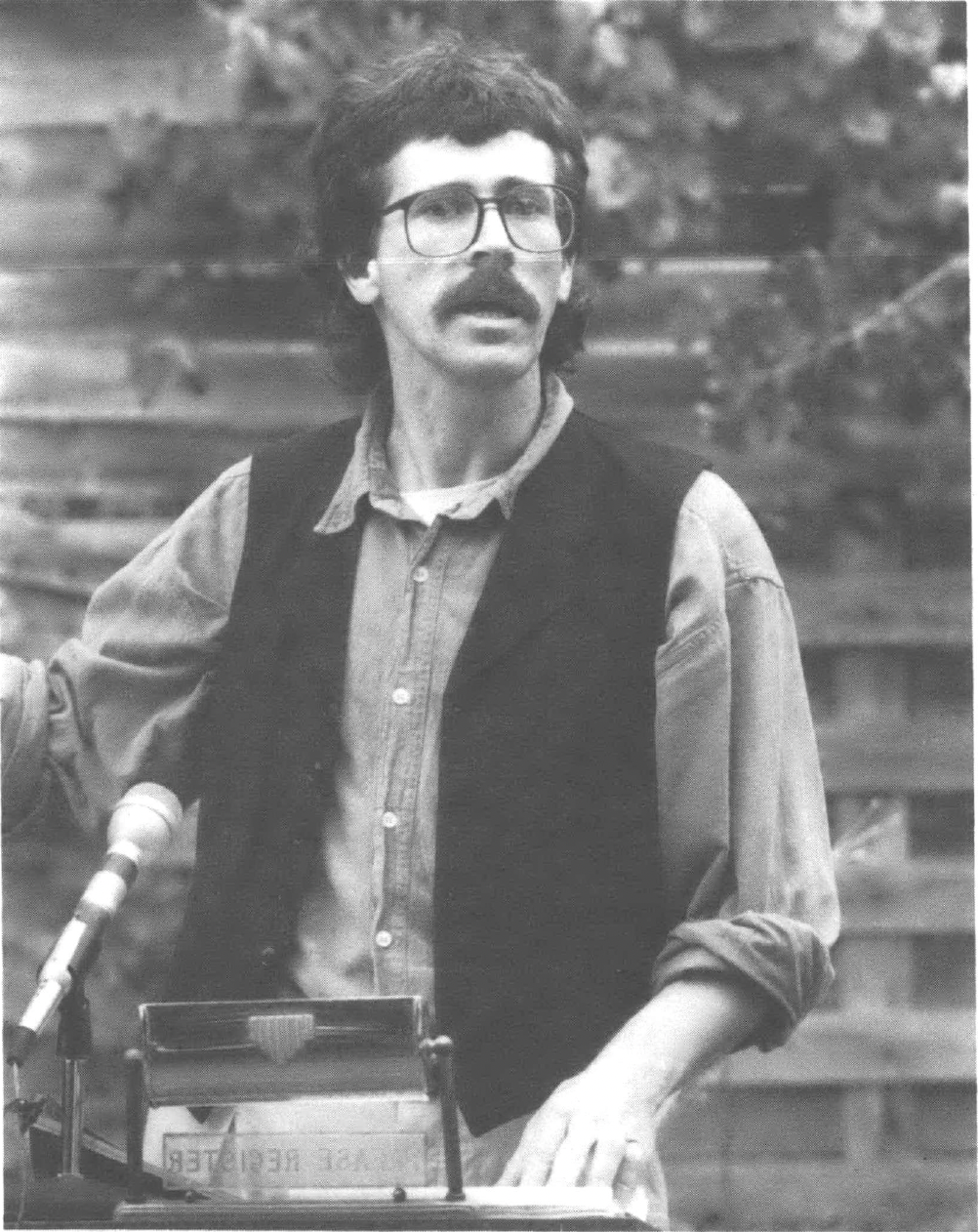

Jesse Wimberley

Jesse Wimberley has been a community organizer with the Piedmont Peace Project for seven years. He worked previously as a naturalist, environmental educator, and researcher. (1996)