Awake, Awake and Fly Away

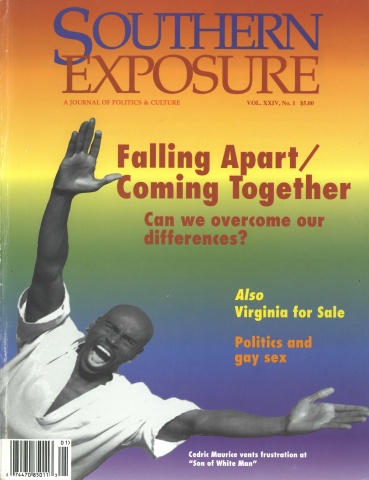

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

On Friday morning, over breakfast, Sterling looked up from the newspaper he wasn’t really reading and said, “I have to attend a conference this afternoon.”

“Oh?” Charmaine said. Charmaine was his wife.

“In Baton Rouge,” he said. Then, blushing slightly, he giggled. He giggled the way a sheep bleats: bha bha bha bha.

Charmaine got up, went over to the counter, and poured herself a second cup of coffee. She glanced over at Sterling. The old fool. He was so transparent she was tempted to grab a bottle of Windex and shine him up. Instead she pressed her lips together and felt the inside of her squashed lips with her tongue.

“Supposed to be hot today,” Sterling said. “Heard it’s gonna be a corker.” It was mid-September. The city was going limp, the trees taking on a sad, brownish-greenish veil.

Sterling got up, stretched, and fumbled around in his pockets for a little while. Then he went upstairs. A minute later, she could hear him thumping around, searching for something she knew he’d never find. He was always putting things down and losing them. In the past, Charmaine would go through the house after he left for work, and put everything in order: his glasses in their faux-leather glasses case on his dresser, his papers in a stack on his desk, his comb and hairbrush side-by-side on the bathroom cabinet. She couldn’t stand the clutter. But something had changed, and now she couldn’t care less. The entire house was filled with things that didn’t belong anywhere, and she listened to her husband bumping into the furniture with something akin to glee. A more useless man would be hard to find.

She waited until after he was gone to survey the damage. It wasn’t impressive. He’d left the notebook in which he’d been recording his latest ideas about macroeconomics and the law on the back of the toilet, his belt under one of the throw pillows on the love seat in the den, and one of his shoes — brown suede with crepe soles — seemed to be missing. The other was half hidden under the bed. In the dark, cluttered room that had once been their oldest child’s bedroom but now served as Sterling’s home office, she found a pile of wadded up Kleenex, an American Express receipt from a place called the DixieLand Courtyard, and the program notes for a concert by a modernist composer she’d never heard of.

She threw out the notebook — it was small and narrow-ruled with a shiny cover the color of mint — and left the rest of his junk where it was. Then she cleared a place for herself on the bed, sat down, and called her best friend, Mary Ann Lewis, to tell her that she was sure of it: Sterling was fooling around again.

“I can’t believe it,” she told her friend. “Except that I have to believe it because he’s just so stupid, in that thudding, duh-uh way men have, for me not to believe it.”

“Oh sugar,” Mary Ann said.

“I just can’t believe it,” Charmaine said again. It was all she could think of to say, because even though she was a talkative and gregarious woman, she was used to dealing with intangibles, and Sterling had become too tangible for her to make sense of.

“Jesus H.,” Mary Ann said. Mary Ann never cursed outright, but continued to use the swearing style that had been popular among girls of her set when she was an undergraduate at Newcomb.

“God only knows what these girls see in him,” Charmaine said. It had been embarrassing enough last time. He’d chased every student he could get his hands on — everyone had known about it. “He’s fatter than a hippopotamus, can’t even get up the stairs without breaking into a sweat. You should see the man eat. He stuffs his face. You’d think he was a starving man, the way he dives into his dinner.”

Mary Ann said, “It must be the messiah thing that some girls get. You know, a crush. Didn’t you ever have any crushes on your teachers?”

“Yeah,” Charmaine said. “But not on some old geezer like Sterling.”

“I see what you mean,” Mary Ann admitted.

Even Charmaine didn’t know why she wanted him anymore, other than for old times’ sake. In certain circles of the law school where he taught, he was a laughingstock. The younger faculty members, those snide Yankees with specialties so rare that Charmaine couldn’t get them straight in her head, called him “W.B.” — for Windbag — behind his back. But hell. These days you had to be black or Puerto Rican or a lesbian or something to even get your foot in the door, she thought. You had to be a black lesbian post-Marxist ecofeminist. The world had gone topsy-turvy crazy or maybe she, like Sterling, was just behind the times — dinosaurs among fleet-footed fawn. She’d come down to this beautiful and hot Southern city 21 years ago to start a new life with him, to invest in his future, to be the kind of good wife to him that her own mother (now a crone, hidden away in a nursing home in Raleigh) had been to her father. And look where it got her. Her house was closing in on her. Her college-age son was doughy of face and mind, his greatest ambition to do well enough on the LSATs to get to a second-tier law school. Her teenage daughter, always moody, was now positively morose, given to writing maudlin poetry about blackbirds.

Awake, awake, and fly away—

on broken wing, cawing,

cackling hideously into the night.

(Or maybe they were poems about witches. Who knew?)

From somewhere in the depths of Mary Ann’s house, Charmaine could hear the sounds of a vacuum cleaner. Mary Ann had divorced her first husband and married a man who’d made a fortune in real estate. Now she lived in an enormous balconied house in the Garden District, and her maid, a too-thin Cajun who never smiled, scrubbed the grout in the bathroom with a toothbrush.

Under her own feet, Charmaine noticed that the dhurrie rug— she’d bought it two years ago at a going-out-of-business sale — had a large, greenish stain on it.

“But are you sure?” Mary Ann said.

Charmaine looked at her free hand. No matter how often she poured lotion over them, her skin was dry, red around the knuckles, and shot through with pale blue veins.

“Sure I’m sure,” Charmaine said. “He left a paper trail a mile long. Receipts, brochures. I wouldn’t be surprised if he came home tonight with lipstick on his shirt collar.”

“Maybe he wants to get caught,” Mary Ann said.

“Christ knows.”

“Or maybe he’s making up the whole thing, trying to make you jealous.”

“No,” Charmaine said after a little while. “He doesn’t have the imagination.”

By the time her daughter, Cassandra, got home from school at four o’clock, Charmaine had gone to the grocery store and the dry cleaners, had her hair trimmed, and weeded her garden. She had had time to consider and then reject her options. Option number one was to confront Sterling with proof of his infidelities and then threaten (as she had last time) to expose him to his children, his colleagues, and his mother, of whom he was afraid. But this no longer appealed to her, if only because it seemed old hat. True, last time it had worked, but last time also she had been hurt. Hurt and afraid — the betrayed wife, playing her role to the hilt. And then the mess that had followed — the trips to the marriage counselor, the shouting matches, the long, earnest late-night conversations that had to be whispered so as not to wake the children. Option number two was to track down the girl and threaten her. This was equally unattractive. For one thing, Charmaine was none too sure that she still had the vigor required to intimidate. Even 10 years ago she was a striking woman, with her thick reddish-blondish hair and white skin and blue eyes and big bosom. But now she was fading into a certain comfortable, if still attractive, matronliness, and she wasn’t sure she could summon forth the sense of outraged sensuality that, in the past, had served her so well. And there was another thing. She wasn’t sure she really wanted to meet the poor stupid bovine-like creature (she pictured a sad-eyed girl with bad skin and a bottom dimpled with cellulite) who for whatever reason was sleeping with her husband. She knew she would just get depressed. Finally, option three was to tell Sterling that she knew about his little friend and that she’d decided as a result to seek a divorce. (In the state of Louisiana adultery was ample grounds, and she knew she’d get the house, the car, and custody, for what it was worth, of their teenage daughter.) This option was also out. For she didn’t — and this was where she came up short — want to leave him.

She didn’t want to be alone and couldn’t picture life as a divorcee. She was afraid that the first time she slept with another man, she’d get AIDS. She was afraid that her insides would dry up. She was afraid that she’d become one of those awful women who join women’s support groups and eventually stop coloring over their gray hair.

It hadn’t been all that long ago that she’d turned heads. The amazing thing was how careless she’d been of her looks, not in terms of how she treated them (for she’d always treated them with respect, dressing herself with care and style, and taking care of her soft white skin), but rather, in their effect on men. Men had fallen all over themselves to catch her eye; before she was married, they’d practically lined up at the doorstep. Even after she was married, and for years and years, they found their way to her, to the kitchen in the back of the house, or to her small and pretty garden, to flirt and insinuate and charm and finally go away angry.

At any rate, once Cassandra was home, Charmaine was no longer able to dwell on her problems. Cassandra was 16 and red-headed like her mother. Unlike her mother, she was skinny and fierce, with no respect for subterfuge. She had three earrings in her left earlobe, and she outlined her lips with brown lip pencil. She was wearing an ankle-length flowered dress of the kind hippies used to wear, which had the odd effect of making her look like a small girl playing dress-up. Though she went to a Catholic school, she had no sense of propriety. In the early ’80s the school had done away with teaching all but the most superficial sense of sin. A terrible time. Jimmy Carter in the White House and hemlines dropping faster than the price of oil.

Now Cassandra threw her books down on the love-seat (the same one where, earlier, Charmaine had found her husband’s belt), turned around, and said, “I’m going to have an abortion.”

Charmaine bent down to pick a piece of lint off the floor, then thought better of it.

“Aren’t you going to say anything, Mother?” Cassandra said. There was a small hole in the seam of her dress a few inches from her armpit.

Charmaine collected herself. If this were a movie, she thought — but then dismissed the thought from her mind for being too trite. “What is it that you would like me to say?” she said.

“All right then,” Cassandra said. Her skin flamed red, then went white again. She was a pretty girl. As pretty, in her own way, as Charmaine herself had been. But there was no refinement in her looks, no artistry to her movements. She was all reaction: a steaming stew of instinctual yearnings. In some ways, Charmaine preferred her dull dull son, Billy. At least he didn’t make you perform every time you had to see him.

“In that case,” Cassandra continued. “I’m not going to have an abortion!”

“In what case, dear?” Charmaine said. She had a headache coming on. The coffee table in front of the love seat was cluttered with Sterling’s things — looseleaf note paper covered with his scrawl, ancient copies of obscure law reviews, paper clips, dried-out ball point pens.

“I mean,” she said, “if you don’t even believe me.”

Charmaine stared at her. “And I absolutely, no, I positively, I completely loathe and detest the hypocrisy of the so-called intellectual classes, to which, may I remind you. Mother dear, you and your husband have laid claim to?”

In addition to writing poetry about blackbirds, Cassandra had been reading Jane Austen. It was an odd combination, Charmaine thought — bad poetry, an even worse sense of personal style, and Jane Austen. Of course, she herself had gone through a Jane Austen stage — doesn’t everyone? — but she’d always been able to keep a cool head.

“Dear?” Charmaine said. But it was too late. Cassandra had hurled herself into her bedroom and locked the door.

She tried anyway. She knocked, and, hearing nothing, said, “Dear?”

“What if I were to tell you that I’m a lesbian?” Cassandra said in a voice thick with sobs. “What would you say then?”

What she should have said, she thought later, was: “If you’re a lesbian, then I wouldn’t think you’d have to worry about pregnancy, unless they’re doing things these days that hadn’t been invented in my day.” How, exactly, did women make love to each other, anyway? With their hands? With their mouths? Or did they have to employ specially designed objects, the kind purchased from catalogues that used to be advertised on the bulletin boards of French Quarter bookstores? It was a subject that Charmaine had briefly been interested in. But she didn’t say any of that, because she was just too stunned to make a rejoinder as she stood in the sunlit clutter outside her daughter’s bedroom door.

The last thing she needed was a pregnant daughter. Of course if Cassandra really were pregnant, and Charmaine wasn’t at all sure that she was, then steps would have to be taken. Counseling. An appointment with a doctor. And then the abortion itself, with all its attendant misery, its moral failings, its ordinary awfulness. Talk and then more talk — with Cassandra’s future therapist, with her school counselor, with Cassandra herself, and yes, even with Sterling. God, just what Charmaine hated. Getting down and dirty with various M.S.W.-wielding nitwits.

Instead she tapped gently on the door and said, “I’m here if you need me, Cassandra. I want to talk. Whatever it is, I want to help you.” But she hated the sound of her own words. She hated how much she meant them.

When Sterling came home a little after 6:00, Cassandra was still locked in her bedroom, and it had begun to rain.

He walked into the kitchen, where Charmaine was sitting at her desk paying bills. He mopped his brow with a dish towel, and said, “The Lord giveth, the Lord taketh away.”

“What, Sterling?” Charmaine said.

“We sure do need this rain,” Sterling said. “Sure was a corker today. Thought my tires were going to melt.”

“Uh huh,” Charmaine said. She didn’t know why he had to try so hard and be so bad at it.

“On the way to Baton Rouge,” he said. “Highway packed, too, bumper to bumper, all the way from the airport to Gonzales almost.”

“Uh huh,” Charmaine said again.

“Interesting conference, though,” Sterling said. “About the ultimate constitutionality of the so-called balanced budget movement.”

“Uh huh,” Charmaine said.

“Frank Simmons — you remember him, handlebar mustache, smart as a whip, over at L.S.U. — he was Chair.”

Sterling sat down heavily at the kitchen table, then got back up, then went over to the sliding glass doors in the back of the house to watch the rain. “Where’s the kid?” he finally said.

Charmaine shrugged. She hadn’t planned what if anything she was going to tell Sterling today. As it was, Cassandra intimidated him. She didn’t know what he’d make of a pregnant or maybe not-pregnant but still clearly disturbed daughter. “Look Sterling,” she finally said.

He blushed, then giggled: bha bha bha. Lately he had grown his grayish-orangish hair long on top and combed it sideways across his bald spot.

She closed her eyes and shook her head. Look, Sterling, you fat old philandering windbag laughingstock jackass, you’ve got to stop this nonsense now. What is wrong with you, that you don’t see the beauty that’s right before your eyes?

“She’s upstairs,” Charmaine said. “In her bedroom. She said she’s pregnant, but then she said she isn’t. Then she told me that she was a lesbian. Then she locked herself in her room.”

His relief was immediate and palpable. His skin returned to its regular hue of ripe peach, his breathing became less labored, and his gut, which he’d been sucking in as if he were preparing to take a blow, billowed out over the top of his unbelted trousers.

“Well,” he finally said, “I suppose if she is pregnant, then she’s going to have to have an abortion. Right? I mean. What I mean is, do you think she actually is pregnant? I mean, our little girl?”

“I don’t know,” Charmaine said.

The kitchen needed a complete overhaul. Because if she were, after all, going to leave her husband, she’d want to start anew, sell this dump, and move somewhere else, perhaps into one of those pretty brick houses on the other side of the lake. For one thing, the wallpaper was so old that it no longer hung straight but was rumpled here and there along its seams. The countertops and cabinet fronts were dark with use. There was a large water stain on the inside of the refrigerator in the shape of a Rorschach ink blot.

From upstairs she heard the sounds of slamming doors, then running footsteps, and then her daughter’s angry voice crying “Double fuck.”

“Don’t run away from me, young lady,” Sterling said a moment later. “Don’t —” but Charmaine couldn’t hear the rest of it. It wasn’t like Sterling to go around making proclamations. His paternal style was laissez faire. He’d smile and joke, and, when the kids were little, he’d given them piggy-back rides. “Don’t —” Charmaine heard again, which made her wonder if perhaps Cassandra knew, in some intuitive teenage way, that as a husband Sterling wasn’t all that he should have been. But a moment later, when she heard something that sounded like something shattering — it could have been a vase or water glass or window or paper weight — she forgot what she was thinking and went upstairs to see what the trouble was.

Cassandra had hauled her mother’s old suitcase from the top shelf of the linen closet and was hurriedly stuffing her things into it. There were marbles all over the floor, some still rolling. Charmaine or someone must have shoved them in the back of the closet years ago, perhaps when the children had outgrown them. They were the old-fashioned kind, blue and red glass, with swirls and sparkles inside, and they shone in the dust-speckled light.

“Look what she’s doing, Charmaine, just look at her,” Sterling said. He was sitting on the love seat, out of breath. “Do you mean to tell me that you’re running away?” He turned back to his wife. “She’s packing her things, Charmaine. Just look at her. She’s packing her things.”

“I can see that,” Charmaine said.

“You want me to kill my baby,” Cassandra said. “And I’m not going to do it. I’m not. I don’t care. It’s my body and my baby and I’m not killing it just because you want me to.”

There was a scrap of paper on the floor underneath Charmaine’s toe.

Into the night —

Take flight —

Black.

White.

Sterling got up from the love seat. His face was red. “I’ll be goddamned if I’m going to be made a grandfather at my age. And maybe while we’re on the subject, perhaps you can enlighten us as to the brave squire whose issue you’re carrying?”

“Oh, why can’t you just shut up?” Cassandra said. “You sound like some weirdo in a bad book.”

“And listen to how she talks to her father,” Sterling said.

“Charmaine, did you hear her?” He sat back down again.

It was strange. Cassandra’s usual style was to ignore her father. And because he was afraid of his daughter, he was happy to let her ignore him. Charmaine looked to her husband, then to her daughter, then back again to her husband, and wondered what she should do. Clearly, she thought, this was a crisis. It had all the earmarks of one.

“Calm down, everyone,” she said.

Cassandra began to wail.

“Are you, or are you not, pregnant?” Charmaine said.

She wailed even harder.

“I don’t know,” she finally said. Her shoulders, under her flowered ill-fitting dress, sagged, and a moment later she flopped face down on the bed.

“I see,” Charmaine said. She waited a minute, then went into her daughter’s bedroom and closed the door behind her. “Are you trying to tell me that you’re a lesbian, dear?” Charmaine said.

“Oh God, Mom,” Cassandra at last said. Her face looked stricken. It was long and pale and child-like, with big eyes.

“Why are you so stupid?”

“Am I stupid?” Charmaine said, but Cassandra didn’t answer.

At last she succeeded in calming her daughter, and though she still didn’t understand what, if anything, had happened, she felt sure that Cassandra wouldn’t bolt, at least not tonight. She made her lie down and breathe deeply, and then, when it looked like she was beginning to relax, Charmaine went downstairs and made her some Campbell’s tomato soup. She put half a Valium in it, then sat by the side of the bed while Cassandra, now wearing the oversized Minnie Mouse T-shirt that she slept in, drank one cup of soup and then a second, and then fell asleep. Outside it began to rain again and the sky went from blue to pink to purple, and Charmaine wondered what it was about this beautiful, hot city that made so many people go crazy.

Mary Ann called around 8:00 to check in, but Charmaine told her that she couldn’t talk. Then the man from the dry cleaner’s called to say that he didn’t think he could get the stain out of the dhurrie rug that she’d dropped off that morning. Then Sterling emerged from his office and asked her what was for dinner. She stared at him. He had a pen stuck behind each ear, and his face was so fat he had jowls. He looked like a hippo. It was hard for her to imagine that just a few hours earlier he’d been conjugating the verb with some weak-eyed and most assuredly neurotic co-ed. Only these days, of course, they didn’t call themselves co-eds. There were as many girls as boys in the law school, and all of them looked alike: drab and asexual in jeans and white button-down shirts.

“I didn’t make dinner,” Charmaine said flatly.

Sterling opened his mouth to say something, then closed it, then opened it again. “What about her?” he said, indicating with a nod of his head the upstairs bedroom where Cassandra slept. But she didn’t have an answer for him, because when she was Cassandra’s age, she’d spent her days and nights dreaming of love, and though she’d been brave, she’d never been silly. She’d been beautiful and full of life and smart, and she’d known her worth, and held out. Mistakes, she’d known even then, were for other people. Her only other up-close experience with teenagers had been with her son, Billy, but Billy was as innocuous as Christmas. A good boy, who made good grades and dated good girls who, like Sterling, giggled often, Billy was sweet, earnest, and loyal as a collie.

“Do you think she is?” Sterling said.

“Is what?” “Pregnant.” He said it noncommittally, as if he were ordering a turkey on rye for lunch.

“I think it’s more likely that she’s scared,” Charmaine said, closing her eyes. “I don’t think even she knows what she’s scared of. Herself. Her future. Girls at her age —” but then she stopped, because the truth was that she had no idea what girls at her age were like. She herself had never been the age Cassandra was now. She’d gone from being a child to being a woman, then a mother, and, then, without warning, a frump — unloved, misused, desexualized.

“Girls at her age have just gone completely out of their minds,” Sterling continued for her. “It’s something in the air, maybe. Or it’s their hormones. Hormones jumping all this way and that. Jumping out of their skins. And that crap they watch on television, that V.T.V. or whatever it’s called, those rock stars performing fellatio on their microphones.”

Charmaine stared at him.

“And it’s not enough that you try to raise ’em on the straight and narrow, give ’em love and some kind of education and try to instill in them a sense of decency, because sooner or later they’re going to look around at the fellows on that video show having sex with their guitars and realize that the best you can do is grow up and marry some poor decent fellow and grow old together in a house, and maybe have a kid or two, maybe eat some good food, get a little drunk, and when it comes right down to it, that’s not much, is it? I mean, compared to what you think your life should be.” Sterling abruptly stopped and sat down.

“Why Sterling,” Charmaine said, truly moved. “That was something. Really. That really was.”

He looked at her, then down over his big stomach at his shoes, then back out the sliding glass doors, to the dark, steaming garden. “Why don’t you love me anymore, Charmaine?” he said.

“What?” You hound dog. You snake. You pompous pontificating old fool.

“Because if only you loved me —” he said, but he didn’t finish.

Night.

White.

Soaring — beating wings — toward the light.

In the darkness of my

Vampire bite. Her husband was snoring beside her and her daughter was drugged and asleep in her childhood bed, but Charmaine was wide awake. She was wondering what she should do, wondering how she had come to this place in her life, wondering if it was too late to save her own soul.

Tags

Jennifer Moses

Jennifer Moses' fiction has appeared in Commentary, Mademoiselle, The Gettysburg Review and other publications. She lives in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and writes regularly for the Washington Post. (1996)