All God's Children?

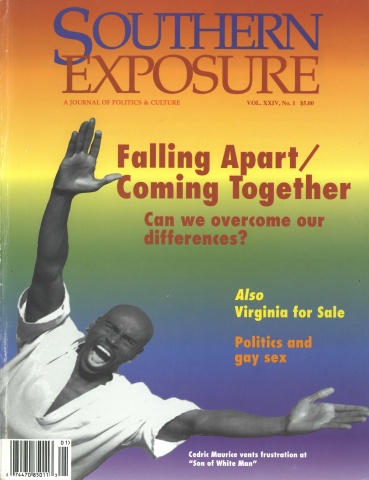

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 24 No. 1, "Falling Apart/Coming Together." Find more from that issue here.

Reverend Gerald Smauldon didn’t like what he saw around him. In his opinion the nation was headed on a “morally destructive course.” Yet his fellow ministers were doing nothing to address this decline. “I had become greatly burdened over what I perceived to be a lack of concern on the part of many fine black church leaders,” says Smauldon, an associate minister with the Family Worship Center of the Church of God in Christ in Columbia, South Carolina. “Though my initial instinct was to criticize my fellow black Christian leaders for their silence, God in the gentleness of His Holy Spirit instructed me otherwise.”

So instead of criticizing, Smauldon formed an organization called the Black Christian Coalition. The coalition, according to its founder, is a multi-racial prayer, education-based, social outreach program. The coalition also conducts abortion counseling and education seminars to “expose the racism associated with abortion,” surveys candidates for political office on their views, and has a Government Policy Department that examines government policies affecting church and society.

“It is my earnest desire that black Christians, as well as Christians of other races, through the Black Christian Coalition will be drawn together as one to do the complete work of God here on earth,” Smauldon says. “The primary focus of the organization is to engage in those projects that are beneficial to mankind.”

Commendable goals. But not everyone shares in Smauldon’s vision. To many critics like Reverend Tim McDonald of the First Iconium Baptist Church of Atlanta, organizations such as the Black Christian Coalition are, more than anything else, an attempt on the part of the predominantly white religious right to attract minorities in support of its conservative ideals. “I don’t think their agenda is spiritual in any form or fashion,” says McDonald.

Smauldon dismisses these allegations. “[The Black Christian Coalition] is not a political organization, nor is it the secret arm of any church or para-church institution,” he says.

There is no apparent connection between the Black Christian Coalition and the Christian right. Few people have even heard of the organization. But it is the kind of group through which the Christian right is making a concerted effort to reach minority groups. Over the past year, members of the Christian right — particularly the 1.5 million member Christian Coalition which is perhaps the dominant force in today’s Republican party — have helped elect politicians sympathetic to their beliefs. It has also begun meeting with leaders in the Catholic Church, rabbis, and black ministers. The group plans to send out voting guides to black churches and soon expects to run ads on black radio stations.

“We are about serious coalition building,” says Brian Lopina, Director of Government Affairs for the Christian Coalition. “We welcome all people of faith that support the agenda of the Christian Coalition.”

Adds Christian Coalition Executive Director Ralph Reed, “We have a vision. We are building a broad-based, inclusive organization: Catholic, black, brown. We’re hot because we are on to something.” That something, according to Reed, is a “true Rainbow Coalition, one which unites Christians of all races under one banner to take back this country, one percent at a time, so we will see a country once again governed by Christians . . . and Christian values.”

So far the results have been mixed. Outreach has resulted in the formation of a Catholic branch of the Christian Coalition, and Jews now make up 2 percent of the Christian Coalition’s membership, according to Lopina. Overtures to the black community have been less successful. At Christian Coalition meetings it’s hard to find blacks or other people of color. And the problem is not confined to the Christian Coalition. Although groups like Focus on the Family, an anti-abortion group, and Promise Keepers, an all-male religious organization, contend that they too are actively recruiting people of color, the results on the ground are hard to come by.

“Most African-Americans view the Christian Coalition as firmly in bed with the Republicans,” says Clyde Wilcox, a professor of Government at Georgetown University and author of God’s Warriors, a study of the religious right. “In doing nonpartisan, value-based things, the African-American community is a potential reservoir of support for the Christian right,” Wilcox adds. “But once groups like the Christian Coalition mention issues like support for a flat tax or endorsing Phil Gramm for president, it doesn’t sell well with the African- American community.”

Wilcox says that support for the religious right among people of color also drops the more they know about its overall agenda. He gives school vouchers as an example, a program supported by the religious right and a number of blacks. They see vouchers as a way to give parents a choice of private schools and more control over their children’s education. But when blacks realize that under the voucher plan, private schools can keep records and meetings private and that it allows schools to withhold data on drop-out rates, test scores, and racial and gender breakdown, support for the plan drops tremendously.

Yet when it comes to school prayer, opposition to homosexuality, pornography, and abortion, the religious right gains tremendous support from the black community. “The only way organizations like the Christian Coalition will get significant support from the black community is if they stick to moral and spiritual issues and stop being political,” says Wilcox. It’s not hard to understand the attraction of many African-Americans to the rhetoric of the religious right. Dr. C. Eric Lincoln, a professor of religion and culture (emeritus) at Duke University, suggests we take a look at black history and the role religion plays in the life of many African Americans.

“The black church and the black community is an Old Testament, Biblical church and community,” says Lincoln. “The black experience is such that God is real. Teachings about morality and punishment for transgressions are real. This is the black interpretation of reality.

“So anyone preaching the gospel of the Old Testament will find a responsive congregation in the black community,” Lincoln says.

The evolution of these beliefs, says researcher Deborah Toler, who is writing a book on black conservatives, can be found in the early teaching of the newly freed slaves. “Most of this schooling was carried out by white missionaries and abolitionists from the North,” Toler says. “These white instructors were intent on imparting the Puritan work ethic and morality in black schools of the day.” According to Toler, “moral sexual behavior” and “conventional family lives” resonated with newly freed slaves because of sexual exploitation and the denial of the right to family life under slavery.”

In a recent Gallup poll, 30 percent of African-Americans considered themselves a part of the religious right. Blacks who were Protestant were more likely to consider themselves part of the religious right. But only 17 percent of whites surveyed in the poll considered themselves part of the right.

In another poll conducted by The Wall Street Journal and NBC News, 87 percent of blacks agree that there is a need for stricter laws to curb pornography in books and films; 75 percent of whites take that view. And 53 percent of blacks agree that a moral decline is a major reason people are on welfare, while 58 percent of whites feel that way.

But even though polls indicate that many blacks consider themselves part of the Christian right, the term is not always equated with both political and religious conservatism as it is with much of the white Christian right. African Americans tend to vote more liberally than their white counterparts and are often less conservative on political issues. Yet with the level of conservatism in the black community on social issues in some cases higher than in the white community, the Christian right has had some success in targeting blacks in the South on specific aspects of its agenda:

· In Louisville, Kentucky, black churches were recruited in an anti-gay rights battle when the Board of Alderman voted down a bill protecting gays from discrimination in 1992. Anti-gay organizers used a video, Gay Rights/Special Rights, which featured portions of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech interspersed with images of gay people kissing. The film had been distributed to black churches across the country to build resentment toward gays and lesbians. Said one of the anti-gay organizers in Louisville, “Black churches were extremely important to our winning effort. Blacks were offended by the idea of extending civil rights protection to a form of sexual behavior.”

· In Durham, North Carolina, a black woman, Victoria Peterson, publishes the conservative newspaper New Voice/New Generation. Peterson is a staunch antiabortionist and consistently writes fiery editorials promoting much of the conservative Christian right agenda — school vouchers, an end to abortions, and welfare reform. The paper also features a regular column from the conservative John Locke Foundation. The Raleigh, North Carolina, foundation is one of the leading conservative think tanks in the country. Though not a formal member of the Christian Coalition, Peterson says she supports most of the organization’s positions. “Most African Americans in the Christian right are comfortable because we are amongst our Christian brothers and sisters even if they are white,” Peterson says.

· In Jackson, Mississippi, the Christian Coalition supported Bishop Knox, an African-American principal from Wingfield High School who was fired from his position after allowing students to pray. More than 4,000 people from the black community and Christian Coalition turned out on the state capital in protest.

· In Georgia the Christian Coalition recently named its first African-American board member. And last July, 125 black ministers associated with the coalition met in Dallas, Texas. “We are seeing a dramatic increase in the number of African Americans who are willing to better represent the moral conscience of our community by organizing with the Coalition,” says Stephan Brown, who is in charge of outreach to communities of color for the Christian Coalition.

On a broader level, the Christian right has had a hard time recruiting African Americans in meaningful numbers. Only two high-profile supporters of the religious right are African American. Alan Keyes is a Republican candidate for the presidency and has been a darling of Christian Coalition leaders, and Kay Coles James is Virginia’s former Secretary of Health and Human Resources. Before that, she was vice president of the Family Research Council, a conservative anti-abortion advocacy group affiliated with Focus on the Family, headed by James Dobson. (Dobson distributes Gay Rights/Special Rights, the video that helps keep the gay and black communities divided.) Both Keyes and James are former government appointees under Republican administrations — hardly the kinds of African Americans likely to attract less-conservative blacks to the ranks of the religious right. This shows in the limited success of recruitment efforts.

Many African Americans have not forgotten that some of the leaders of the Christian right have often opposed efforts that would benefit their communities. Minister Jerry Falwell, who led the now-defunct Moral Majority, was an outspoken opponent of integration in the 1960s. More recently, the minister supported the apartheid regime in South Africa and called Bishop Desmond Tutu “a phony.”

In 1982, Falwell also attacked efforts by the federal government to remove the tax exemption status of private schools that discriminate against African Americans. Falwell condemned the decision, stating, “Personally, I would not practice racism, and I think my record proves that. But I would die for the right of other religious groups to do so for religious reasons.” Yet Falwell has sought to gain black support for his anti-gay crusade. He has begun mailing out appeals to blacks saying, “a person is a moral pervert by choice and should not be rewarded . . . as a minority.”

Pat Robertson, founder of the Christian Coalition, has also been an opponent of many policies that would benefit blacks. Although his 700 Club and other organizations within the Christian Broadcast Network employ many African Americans and Robertson counts ex-football great Rosie Grier as one of his friends, the televangelist has been a vocal opponent of civil rights laws. In 1988, Robertson applauded Ronald Reagan’s veto of the civil rights bill, saying that the bill would have “expanded the power of the federal government in a radical way to control private institutions including religious institutions.”

More recently, Ralph Reed, speaking at a dinner for the Detroit Economic Club, boasted that the Christian Coalition spent $1 million to lobby in support of the Republican’s Contract with America. Support for the Contract can hardly be seen as a way to reach out to blacks since most of the proposed cuts and reduction in services outlined in the Contract will fall disproportionately on African Americans.

“These people remind me of people who have in the past used religion to justify slavery,” says Reverend Tim McDonald of the First Iconium Baptist Church in Atlanta. “They have another agenda which has nothing to do with God. At the core it’s [the religious right] segregationist and racist.”

But the conservative New Voice/New Generation editor Victoria Peterson calls McDonald and other critics’ statements “scare tactics. I’ve heard the same arguments about black men, that they are all rapists and thieves, and we know that’s not true,” she says. “The Christian Coalition [and other religious right groups] are not racist. They are concerned about the moral welfare of this country as are a lot of African- Americans.”

The religious right has much to gain by recruiting African Americans. A strong coalition of minorities within the religious right would be detrimental to the base of the Democratic Party and a boon for the conservatives in the Republican Party. And there is a window of opportunity for the Christian right because Democrats have basically conceded the issues of moral, family, and spiritual values to the Republicans and the religious right. It’s a move that could prove dangerous, according to Ronald Walters of the Center for Constitutional Rights in Washington, D.C. “If the religious right and the Republicans could take 15 percent of the African-American vote, they could be in power for some time to come,” says Walters. Black politicians and the Democratic Party have “to understand the core conservative values in our communities and not overlook them.”

That task won’t be easy, says Reverend McDonald, because “blacks don’t like to be put in a posture of fighting each other over social issues like homosexuality. Most black ministers are not going to come out and defend a controversial issue like this,” he says.

But even McDonald admits that the Christian right’s efforts are beginning to show some effect on the black community. “It’s not that they are going to get a lot of support from the black community,” he says. “But when you start with nothing and end up with a little something it’s better than what you had.”

Brian Lopina of the Christian Coalition admits as much. “The Christian Coalition’s agenda is one big agenda,” he says, “not one political and one spiritual. But we are glad to have any support we can get on our agenda. Every little bit helps.”

How this help will play out in the 1996 election and beyond remains to be seen. But one thing is certain — the religious right has established itself as a major player in the political arena and has set its sights on gaining a share of the minority vote. Whether this effort will bear fruit is not yet clear. Speaking to a group of supporters recently, Reed declared, “We are no longer going to concede the minority vote to the political left.”

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.