Wrong Side of the Track

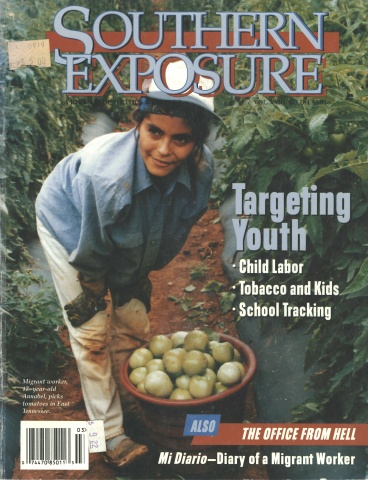

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

“The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worth while, depresses and crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro by making him feel that his race does not amount to much and never will measure up to the standards of other peoples.”

—Carter G. Woodson from The Mis-Education of the Negro, 1933

In late 1987, a loosely organized group of citizens in Sylvania, Georgia, investigated a complaint from a black teacher who said she was being harassed by white students at the rural Southern Georgia Screven County High School, where 55 percent of the students are black.

The school’s administration had failed to handle the issue after the 20-year veteran English teacher reported that some white students called her “nigger” and “bitch” and, in one incident, knocked her down. “The issue was ultimately resolved with some of the [white] children being suspended,” said Karen Watson, coordinator of Positive Action Committee, the group that formed to look into the incidents. “While we were investigating what happened, we found out the problem went much deeper than this teacher being harassed.”

The African-American students at the school were concerned about tracking in the school. “They told us they found themselves always being placed in lower-level classes. And when they got to high school, they were working at a much slower pace than other students,” she said. “They also wanted to know more about unfair disciplinary practices and why the school did not have any black counselors.”

The local branch of the NAACP had tried to address issues in the school system without success, the group found. Besides, life was made hard for black people who challenged the system. “People got harassed. They had nasty editorials in the local paper. People in our group have been followed and had lights shined into their houses,” Watson said. “Notes were left at the building where we were during tutoring. One note said, ‘I’d watch myself if I were you.’”

Last summer shots were fired into Watson’s home. She was not injured. “This is one of those small rural counties where certain things are supposed to be accepted,” she said. Watson continued her full-time work with the committee, which is affiliated with the Center for Democratic Renewal in Atlanta. The center gives the committee a budget that pays Watson’s salary. The group also depends on volunteers and in-kind support from its members.

The threats and intimidation did not stop the committee during the eight years it took to gather information about tracking and file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education. They eventually got what they wanted. Earlier this year, after the Department of Education said it would investigate whether tracking created racially segregated classrooms within the district’s three schools, the Screven County School District agreed to end tracking. The agency’s Office of Civil Rights in Atlanta also found that the district’s hiring and promotion practices and the way it disciplined students were racially biased against black people.

A Segregating System

Screven County’s end to tracking was one small victory against the practice of separating students in the South by perceived academic ability. Critics contend that tracking maintains racially segregated classrooms within integrated schools 45 years after the United States Supreme Court outlawed segregated schools. In many cases, students within the same school are grouped regardless of ability, creating slower-paced classes of mostly minority children and college-bound classes of mostly white children.

Though hundreds of complaints have been filed with the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights alleging that minority students are still being bunched into low-ability tracks throughout the nation, the problem persists.

According to a 1991 report by the U.S. General Accounting Office, the problems of tracking continue due to the Office of Civil Rights’ lax enforcement when it finds evidence of violations. (See “Office of Civil Wrongs.”) In 1992, when the Positive Action Committee filed its complaint with the Office of Civil Rights, the organization was unaware of the report criticizing the federal agency. But the committee did know that the OCR had received several complaints about Screven County schools and had failed to act.

Karen Watson believes that the Positive Action Committee won because it did extensive research, met with Office of Civil Rights officials in Washington and Atlanta, and brought evidence of discrimination in its 30-page complaint. “We worked the issue very hard and made it clear we were going to pursue it one way or the other regardless of what OCR found,” she said. “We were diligent, and we got a good (OCR) investigator. And those were all the factors in why we were able to move this key issue a tiny bit further.”

A Bad Idea

While on the face of it the grouping of students by ability might make sense, there is little justification for tracking. “Generally, tracking is an excuse. Parents and supporters of kids who are perceived to have high ability feel that if these kids are in classes with so-called low-ability kids, their progress will be slowed,” said Thomas E. Thompson of the Department of Education at the University of South Carolina. “What we know of teaching and learning does not support the practice of tracking.” Education researchers like Thompson believe that students with different abilities have more to gain from learning together than from learning apart.

A leading education text, Introduction to the Foundation of American Education, found that tracking is actually damaging to the so-called low-ability children. “The potential for problems generated by ability grouping far outweighs the scant benefits to be gained by rigid grouping,” wrote author James Johnson. “Low-ability groups become dumping grounds for learners with discipline problems, some of whom are not of low ability.” In those classes, low-ability students tend to do badly “because of the teacher’s low expectation of them.” Minority children are particularly affected, he believes. “Problems associated with social class and minority group differences are usually increased with ability grouping. . . . Negative self-concepts are more severe among minority group learners who are assigned to low-ability groups.”

The statistics show that when students are picked for so-called gifted and talented programs, minority children tend to be left out. In fact, tracking has become “second generation segregation,” according to Joel Spring in another text, American Education. Unlike the blatant segregation in the South before 1954, “Second generation segregation refers to forms of racial segregation that are the result of school practices such as tracking, ability grouping, and the misplacement of students in special education classes.” It can be used, Spring contends, to maintain the white power structure, “a method of closing the door to equal economic opportunity for African Americans.”

Tracking is losing favor, and the idea of putting together students of all abilities and with various handicaps is gaining favor. Spring notes that “in 1992, the National Association of State Boards of Education gave its support to the idea of full inclusion.”

But various kinds of tracking are still very much a part of education in the South. Gifted and talented programs are telling. A small proportion of students enter these classes that are packed with interesting projects intended to inspire interest and creativity. Good teachers like teaching in these programs, and valuable school resources go to support the special projects. These programs often tend to exclude minorities.

Tracking and the Gifted

According to 1992 Department of Education figures, West Virginia reported the lowest percentage of minority students in gifted and talented programs in the South. Only 201 — 2.6 percent — of the state’s 7,518 students in gifted programs were members of minority groups, but West Virginia’s minority population is less than 5 percent.

Texas reported the highest percentage of minority students in gifted programs, with nearly 30 percent of the 249,268 students in gifted programs. But more than half of the children in school in Texas represent a minority.

Still, Texas does better than most Southern states in its level of minority participation in these programs, and they take pride in the level of success. Educators do not depend on just test scores to determine who gets into these programs, said Evelyn Hyatt, director of gifted and talented programs. “We use standardized measures such as tests and non-standard measures such as teacher and parent recommendations. We are successful because the state board has ruled that the gifted and talented enrollment must reflect — not match — the population of that district,” Hyatt said.

“We start in kindergarten, where the gifted and talented program best reflects the racial composition of the state.” However, the percentage of minority students declines as students become older. “Far lower numbers of African-Americans and Hispanics pass standardized tests than whites. I see it as a problem of the public school system as a whole, not just the gifted and talented [programs].”

South Carolina is one Southern state attempting to do something about the school system as a whole. The state legislature abolished what is called the general track, a basic curriculum that has been considered unsatisfactory for a long time by teachers and parents. In the new program. Tech Prep, students will be able to choose a liberal arts education or a vocational education.

Tech Prep needs to be carefully monitored, according to Luther Seabrook, the state’s senior executive assistant for curriculum. “Tech Prep scares me because it could be a replacement for the general track.” In addition, he believes that school administrators and teachers still must stop picking winners and losers even before school begins. He explained that it is assumed that white students are ready to learn when they enter school, and they must demonstrate that they are not. However, it is assumed that black children are not ready to learn when they enter school, and they must show that they are.

Vouchers as New Tracking

If Seabrook is concerned that Tech Prep could become another way to track students, Karen Watson in Sylvania, Georgia, is worried that the proposed school voucher plan could be tracking in disguise.

With vouchers, which are under consideration in several states, parents would be able to use their educational tax dollar in any school, public or private. Proponents say that poor and black students would gain an opportunity to attend private schools if they wished. The plan would put pressure on public schools to improve or lose students.

But Karen Watson is skeptical. If parents do not understand the rules, do not have time to find the better schools, or cannot afford the additional transportation cost to better schools, nearby public schools would be the only ones available to poor and black students, she believes. Those public schools would be strapped for funding because the more well-to-do residents would take their school funds to more distant and more expensive private schools.

A report by the education committee of the Pittsburgh Branch of the NAACP found that vouchers in Pennsylvania would be inadequate to cover the tuition cost of most private schools for most minority parents.

Vouchers would give parents about $ 1,000 for tuition. But the report found that the average cost of private schools ranged from $3,000 to $8,000. Since most black parents who send their children to Pittsburgh public schools are on public assistance, private schools would be beyond their economic grasp.

The Pittsburgh report also found that the voucher system would take money from the public school system and support schools that are not required to follow the same admission and testing guidelines as public schools.

“Such a system can only further splinter our community whereby the children of ‘haves’ will be afforded a good education, and the children of ‘have-nots’ will again be economically locked out,” said Eugene C. Beard, chairman of the NAACP education committee.

The Alabama Experience

Though vouchers threaten the quality of education of students who are not well-to-do, the program is only in the proposal stage. Tracking programs are alive and well and do provide a method of ensuring that the privileged retain their privileges. Rose Sanders, founder and project coordinator of the Coalition of Alabamians Reforming Education in Selma, said, “Tracking is the number one enemy of poor children and black children. It affects who gets the best teachers and the best books.”

Societal ills stem from tracking, too. “Drugs and crime can be tracked to an educational system that has low expectations for poor and minority children, and that leads them to have low expectations for themselves,” Sanders said.

She advocates a replacement of tracking with a core curriculum for all students that is strong in math, science, and literature. Sanders also believes that national civil rights leaders need to become tracking opponents, but at present, most of them don’t understand tracking.

Sanders is one civil rights activist who has not always seen the problems with tracking. A graduate of Harvard Law School, she worked as a cooperating attorney with the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund. It was not until 1989, when she learned of the case of a black Selma student who was not allowed to take algebra, that she began to understand the insidious nature of capriciously grouping students. Her daughter, Malika Sanders, was one of the students who spearheaded the takeover of her Selma school after the firing of a principal who dismantled tracking. (See profile of 21st Century Youth Leadership Training Network.)

In Selma, students and parents won a victory against tracking. It was not as sweeping a change as the end to tracking in Sylvania. But the system is attempting to implement a federal judge’s order to replace arbitrary tracking with a method that uses test scores and grades to track students, Sanders said.

The judge’s order, issued in 1993, is part of a ruling that declared Alabama schools unconstitutional because not all schools received equal funding. “There will be tracking, but the tracking will be in line with the rest of the country. They will use criteria to track. But we want to do away with tracking [altogether],” said Sanders.

Derailing the System

While parents in Sylvania are moving toward ending tracking, there is little time to cheer, said Karen Watson of Sylvania. She sees a bigger problem — getting academically impaired students ready to take Georgia’s high school exit exams. This statewide test has been instituted to make sure students have learned what the curriculum was supposed to include.

“The governor wants to have a minimal level of requirement so every kid can do the basics in math and English,” Watson said. “I agree with the exit exam, but these students are going to be held responsible for knowing material that no one has been held responsible for teaching them.”

Georgia Governor Zell Miller has said the state will fund a remedial program to help students who are at risk of failing the exit exam. Something is sorely needed. When a pre-exit exam was given to students in 12 counties, Screven County students scored second from the bottom.

“We are looking at students who have to pass an exit exam, and children who have been tracked are given a watered-down curriculum. They have little or no chance of passing an exit exam now. How do you catch up a child who is two or three years behind?” said Watson.

She sees tracking as the culprit. It continues the miseducation of black and poor children. Watson pointed out that students aren’t taught challenging literature — neither Shakespeare nor Richard Wright — that would encourage students to think on a higher level.

Parents may not realize that their children are not doing well. “The child might get high marks but what Little Billy’s mother does not know is that Little Billy is in the fifth grade doing third-grade work,” Watson said. “She is thinking that her child is on course, but that is far from the case.”

Since studying tracking, Watson said she has seen how it works, though it wasn’t easy to recognize at first. “First, often you find ‘ability grouping.’ It seems logical and harmless. But it should raise a red flag.” It could be a way to separate children by race and class. Whatever the reason, if a child is placed in a low-ability grouping, it may be the beginning of a low-achievement trap.

The placement of children in specifically funded programs like Chapter One may cause similar problems, she said. Congress intended for the program to bring students up to grade level in reading and math. The children were then to be returned to the regular classroom.

In Screven County, however, statistics show students remain in Chapter One through middle school. Then they are placed in general courses in high school. Many parents do not know the truth about their child’s academic status, and the school district does not make an honest attempt to assess students’ needs, Watson said. Parents should become immediately suspicious if the school wants to put their child in any special class. “That is a huge red flag that should go up in your mind.”

If there is a reason that the child needs special help, Watson recommends that a parent get a study plan in writing showing what teachers and administrators intend to do to bring the child up to grade level. “And parents should ask for a date when Little Billy will go back to the regular fifth-grade math class. If you don’t, there is a chance Little Billy won’t see the regular fifth-grade math class again. He will go to sixth grade doing fifth-grade math.

“Our intention is to get state education officials to say to local school systems, ‘This is a practice that will not be allowed, whether you are doing it blatantly or camouflaging it in some other special program so it does not look like tracking.’”

The committee has been working in the courtroom and with school officials. “It has not been high profile for reasons of [personal] safety. We did not set out to achieve that kind of attention. We set out to address a problem. Our success has been due to commitment, being willing to take a lot of chances and investing a lot of ourselves,” she said. “We are happy [about the OCR’s decision] because a lot of organizations have tried to get a grip on what is happening in the schools.

“But at the same time, we have bigger problems. We can win the battle with the school board, and the children can still lose. If that happens, we haven’t accomplished anything.”

Tags

Herb Frazier

Herb Frazier is a reporter with the Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina. (1995)

Herb Frazier is a reporter with The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina. (1997)