This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

On June 11, 1993, 14-year-old Wyonnie Simons of Eastover, South Carolina, went to work on a cattle farm in the nearby town of Hopkins. Originally hired to pick up paper and cut grass, Simons, a dedicated worker, was soon assigned other responsibilities. “He loved to work,” said Betty Simons, Wyonnie’s mother. “He was willing to help anyone.” Just 10 days after beginning the job, Simons was killed while driving a forklift.

Four days after Simons’ death, 17-year-old Jamie Hoffman of Rock Hill, South Carolina, was killed while moving explosives in a warehouse. Provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act could have shut the operation down after the accident, but Southern International, a fireworks company that owned the warehouse, was allowed to stay open because it was one of the busiest times of the year — the week of the Fourth of July.

Both incidents were clear violations of state labor laws and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), the federal law which prohibits youths under 18 from working in hazardous occupations. Both companies could have faced penalties as high as $10,000 under the FLSA, but neither company was fined. According to reports filed by investigators with the South Carolina Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation, the agency that oversees child labor, both companies were issued warnings and “educated on child labor” laws. One of the youths’ families has resorted to litigation: Betty Simons is suing the farm for her son’s death. “It’s not the money,” Simons said. “It’s the tragic loss of life.”

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that there are five million youth in the work force. The federal agency does not collect data on workers below the age of 15. Most young workers have jobs in restaurants, retail, and farm work with most reported injuries in the first two. Farm work is notably unregulated when it comes to young workers, and there are no real estimates of how many young farm workers there are. Such a lack of oversight means that many of the nation’s children may be working in situations detrimental to their social and educational development, health, and in some cases, their lives. But as long as there is so little information available and so little regulation, many of the uses and abuses of children in the work force will remain hidden.

The information that is available from numerous studies and news reports documents violations of child labor laws throughout the South:

♦ In North Carolina, researchers using data from medical examiners found that 71 children and teenagers died during the 1980s as a result of injuries sustained on the job. Eighty-six percent of the deaths resulted from working conditions that violated the Fair Labor Standards Act.

♦ In Florida and Texas, investigations found rampant abuse of children in the garment industry. In one case, Jones of Dallas Manufacturing, Inc., a company that makes clothes for J.C. Penney and Sears, was fined for using a contractor who employed children. One child was 5 years old.

♦ According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Louisiana had the highest percentage of 16- to 19-year-olds killed on the job in the South from 1980 to 1989. The national average of all work-place deaths of 16- to 19-yearolds killed was just over 4 percent. The state ranked third nationally, behind Utah and Oklahoma.

♦ Nationally, a 1990 report by the General Accounting Office, the investigative wing of Congress, found that child labor violations had risen 150 percent between 1983 and 1989. The number of children caught working illegally during this time by the Department of Labor jumped from 9,200 to 25,000 nationwide.

♦ In 1992, a National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) report found that 670 youths age 16 to 17 were killed on the job from 1980 to 1989. Seventy percent of the deaths involved violations of the FLSA. A second NIOSH report found that more than 64,100 children went to the emergency room for work-related injuries in 1992.

Why do children continue to be injured, even killed on the job, despite state and federal laws regulating child labor and two highly publicized crackdowns on violators in 1991? Answers to this question are not easy to find but can be unearthed in data from federal and state departments of labor, reviews of numerous studies, and interviews with state and federal labor department officials, child labor advocates, and medical researchers.

At various times minor reforms have been made at both the federal and state levels, but several barriers continue to prevent children from being adequately protected in the workplace. A patchwork of inefficient data collection systems fails to monitor the total number — much less the well-being — of youth in the workplace. Enforcement of the FLSA is lax. Cultural beliefs about the worth of work for children are strong. Perhaps most importantly, various business trade groups lobby successfully to keep child labor laws from being strengthened and, in many cases, to weaken existing laws.

“Child labor today is at a point where violations are greater than at any point during the 1930s,” said Jeffrey Newman of the National Child Labor Committee, an advocacy group founded in 1904. “It’s very sad, and it doesn’t speak well to our understanding and commitment to our children.”

The Law, The Court, The Law . . .

Efforts to protect children from exploitation in the workplace began in the early 1900s. Unable to get individual states to pass strong laws to protect the health and safety of young workers, reformers like Jane Addams, Lewis Hine, Mary “Mother Jones” Harris, the National Consumers League, and others turned their attention to the federal government. In 1916 they persuaded the government to pass the Keatings-Owen Act, the first piece of federal legislation regulating child labor. Signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, the bill prohibited the interstate commerce of goods produced by children under the age of 14 and established an eight-hour workday for youth under the age of 16.

The bill had tremendous support from the labor unions, churches, and the two major political parties. But two states that depended heavily on child labor, North and South Carolina, objected to the bill’s provisions. After the bill became law, a judge in North Carolina declared it unconstitutional, arguing that it interfered with interstate commerce. The federal Supreme Court agreed, and the law was struck down.

In 1919 reformers tried again. A bill similar to the Keatings-Owen Act passed, imposing a 10 percent tax on the net profits of manufacturers who employed children below the age of 14. Again the North Carolina judge declared the law unconstitutional, this time stating that the act infringed on the rights of states to impose taxation measures. Again the U.S. Supreme Court sided with North Carolina.

Who’s Got the Information? (such as it is)

Researchers and child labor advocates agree that there is a need for a national data collection system to get an accurate idea of the number of young people working, getting injured, or being killed. Among the various data collection systems:

♦ Work permits — Being issued in most states by the local school systems, work permits follow guidelines in the FLSA. However, most states have no central collection point for the number or types of work permits issued. Furthermore, since the FLSA does not mandate work permits, not everyone uses them. According to the Child Labor Coalition, 34 states have some kind of work permits. Fifteen do not require permits.

♦ Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey — Most information on the number of working children is taken from this monthly survey. However, the survey of 600,000 households only records employment data for youth age 15 and older.

♦ National Traumatic Occupational Fatalities Surveillance System (NTOFSS) — Maintained by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the NTOFSS contains information from death certificates for all work-related deaths reported to units across the United States. The minimum age for inclusion is 16, and the cause of death is often a judgment call by the medical examiner, severely limiting the number of reported deaths of children killed on the job. Information obtained from the NTOFSS should be considered conservative, said researchers at NIOSH.

♦ National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) — The Consumer Product Safety Commission’s NEISS contains information on product-related injuries collected from a national sample of hospital emergency rooms in the United States. Through a collaborative effort with NIOSH, data on work-related injuries to persons age 14 to 17 have been recorded since 1992. However, like the NTOFSS, the NIESS is limited. Data are maintained only for product-related injuries, and only for youth 14 and older. The information comes from just 91 hospitals and is extrapolated to national levels, but studies show that only about 36 percent of all work-related injuries are treated in emergency rooms

♦ OSHA Investigations — Researchers have used investigations conducted by OSHA after work-place accidents to estimate adolescent fatalities. But since OSHA only investigates about 25 percent of all work-place fatalities, the data are limited.

♦ Workers’ Compensation Claims — A number of researchers, including NIOSH, have used worker’s compensation claims filed with state agencies to document the number of children injured. The data are limited because youth are less likely to file workers’ compensation claims, eligibility varies from state to state, and not all workers are covered.

♦ Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries — This census, a cooperative venture between state and federal governments, is the most comprehensive data collection system available. States are responsible for collecting data, follow-up procedures, and coding. Reports include about 20 elements, including the demographic characteristics of the worker and circumstances of the fatal event. Information collected includes the employer’s industry, worker’s occupation, equipment involved, activity worker performed, and location of the incident. States obtain this information from death certificates, workers’ compensation reports, and other reports provided by state and federal administrative agencies, such as OSHA, Employment Standards Administration, and Mine Safety and Health Administration. In 1993 state agencies collected approximately 20,000 individual source documents, or about three documents for each fatality case. Although this is the best data collection system available, its effectiveness is limited because the information is based on woefully inadequate data collected by the states.

Reformers then tried to pass a constitutional amendment. Opponents launched an all-out assault. Farmers were told that under the proposed amendment, children would not be allowed to work on the farms. Mothers were told that they could be fined just for sending their children to the store or to run errands. Though Congress approved the amendment, the states refused to ratify it.

Resistance to laws restricting child labor was most apparent in the South where booming textile industry depended heavily on children for a supply of cheap labor. In 1890 children numbered 25,000 in the textile industry. By 1900 the number was 60,000. Until the 1920s, one quarter of the region’s textile workers were boys under the age of 16 and girls under the age of 15.

“The children of the South, many of them, must work,” said one mill owner. “It is a question of necessity.”

Hubert D. Stephens, U.S. Senator from Mississippi from 1923 to 1935, went even further, calling child labor reform a “socialist movement” designed to “destroy our government.” The Senator warned Southern parents that under the proposed child labor laws, “the child becomes the absolute property of the federal government.”

Despite such scare tactics, The National Recovery Administration, a federal agency created during the New Deal, banned employment of children below the age of 16 in most industries in the early 1930s. The U.S. Supreme Court invalidated the restriction in 1935.

Finally, in 1938, during a period of increased automation in American industries and declining child labor, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) passed. The act, which was drafted under the direction of labor leader Sidney Hillman, limited the maximum number of work hours for 14- and 15-year-olds, prohibited certain occupations, and raised the minimum age for full-time employment to 16. The FLSA remains the major piece of federal regulation governing child labor.

Untold Thousands

Today, 57 years after the passage of the FLSA, millions of children in the United States are in the work force, and a large number are exposed to hazardous working conditions. How many? “No one really knows,” said Jeffery Newman of the National Child Labor Committee.

There is no comprehensive national data collection system that accurately tracks the number of working youth, their occupation, where they work, or how many are injured or killed on the job. (See “Who’s Got the Information”) “The numbers that you do get are relatively meaningless,” Newman said. He believes that even the best figures underestimate the number of working children by 25 to 30 percent.

Charles Jeszeck of the General Accounting Office (GAO) won’t go as far as calling the numbers meaningless, but says, “The data that we have on children’s work are very conservative, because they are derived from woefully inadequate data systems.”

To illustrate the extent of under-reporting by employers (to regulators), Jeszeck pointed out that the GAO’s review of independent census data identified at least 166,000 youth age 15 and 16 working in prohibited occupations like construction.

“The number of minority children working may be the most undercounted,” Jeszeck said. “We found that although white youth are more likely to work, minority children are more likely to work in unreportable jobs like agriculture or other ‘hazardous’ industries like manufacturing or construction. They also work more hours a week but fewer weeks a year than whites.” Data on youth below the age of 14 are not routinely collected, he said. “So right off the top you have a distorted picture of working youth.”

On the state level, things aren’t much better. In response to the Freedom of Information Act requests, most state officials admitted that information on children in the work force is rarely collected in a comprehensive or even consistent format.

Kathleen Dunn of East Carolina University and Carolyn Runyan of the Injury Prevention Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had the same difficulty in 1992 when they began researching young workers. “There is no standardized method for keeping track of work-related injuries [for youth],” Runyan said. “North Carolina has a good system for keeping track of injuries and deaths in general, but for youth we don’t expect to need the information, so the data are not routinely collected.”

Part of the problem, Runyan explained, is the perception of doctors or medical examiners who record the cause of injury or death. “Many medical examiners have in their minds some kind of age cut-off when it comes to work-place deaths or injuries,” Dunn said. “So if a child is below a certain age they won’t even consider an injury to the child as a work-related injury. This is a problem across the country,” she said. “What we need is education for medical examiners and standardization of [criteria for] work-related injuries for youth.”

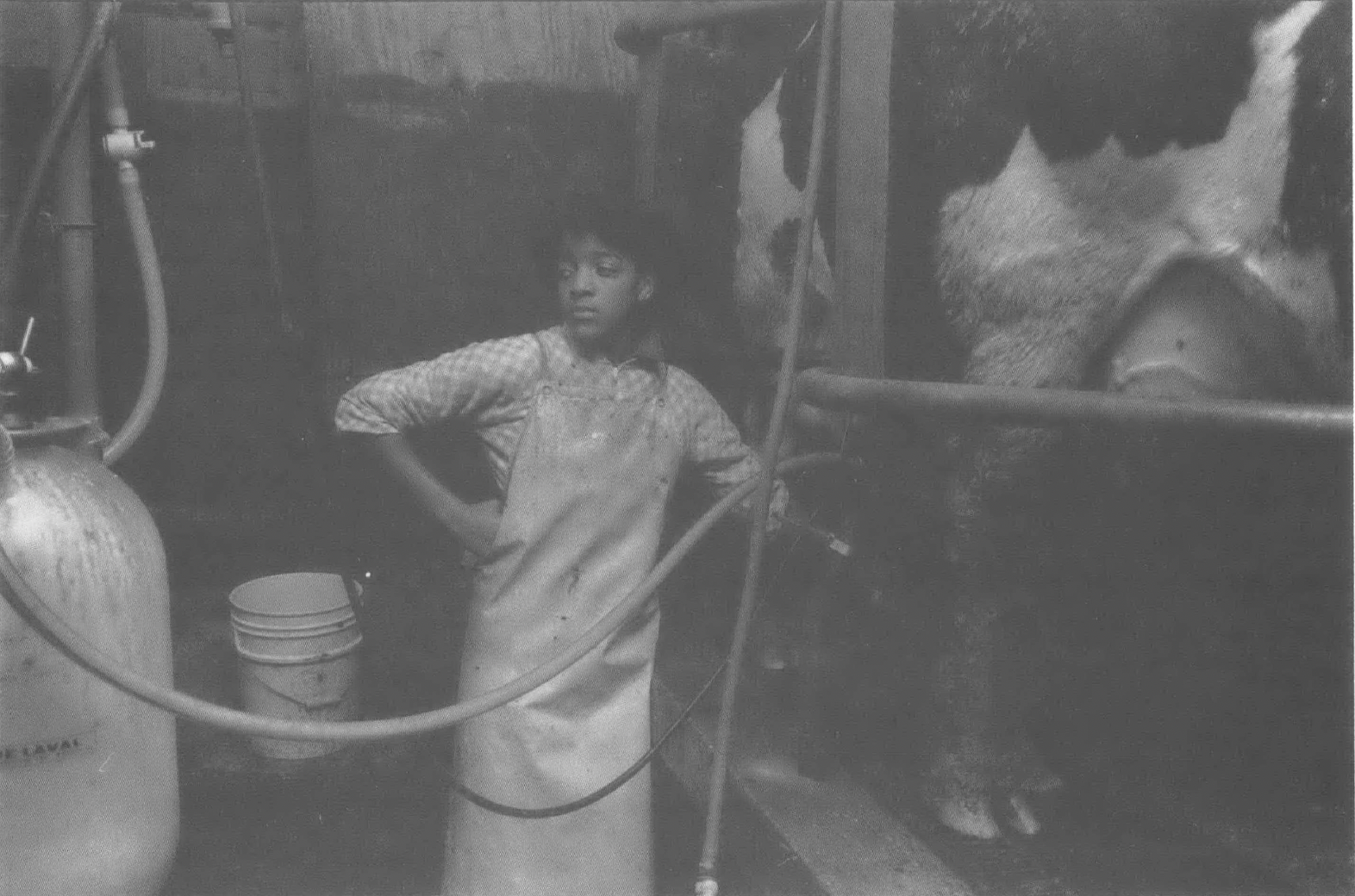

Field of Teens

Counting or tracking the number of young farm workers is even more difficult. Most states exempt agriculture from requiring work permits or age certificates, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ annual survey overlooks millions of children who work on the farm, since the minimum age reported is 15. “But under exemptions in the FLSA, it’s legal for children as young as 10 and 11 to work. The problem is most people simply don’t think that children under 12 work,” said Diana Mull of the Association of Farmworkers Opportunities Programs.

The United Farm Workers Union and studies on migrant children estimate that 800,000 children work in agriculture. According to the Wall Street Journal, 23,500 are injured and another 300 die on the farm each year. All of these numbers are conservative, farm worker advocates say. “There is huge under-reporting in the number of children working in agriculture,” said Mull.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission used to monitor the number of children’s injuries caused by farm equipment and pesticides. But in 1994, the federal agency stopped collecting such data due to budget constraints, said Art Donovan of the commission staff.

Although the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that there are about 300,000 acute illnesses and injuries from exposure to farm pesticides for all workers, little data are available on the actual number of children exposed. According to studies, children are more susceptible than adults to the effects of pesticides. Children absorb more than adults per pound of body weight, but the EPA standards for protecting workers from exposure to pesticides are based on adults only. According to a GAO study, the EPA “believes that studies monitoring field exposure to pesticides and laboratory animal studies on age-related toxic effects indicated no reason to specifically regulate children differently.”

Student Action with Farmworkers

By Laura Neish

Laura Neish is a research assistant with the Institute for Southern Studies and a consultant with Student Action with Farmworkers. Student Action with Farmworker,s P.O. Box 90803, Durham, NC 27708 (919) 660-3652

The South’s plentiful harvests of fruits, vegetables, and tobacco would be unthinkable without the labor of hundreds of thousands of migrant and seasonal farm workers. Working long hours for low wages, often in dangerous conditions, many farm workers have difficulty meeting their own basic needs even as they provide food for the nation’s tables.

One organization working to improve conditions is Student Action with Farmworkers (SAF) based in Durham, North Carolina. Founded in 1992, SAF “brings students and farm workers together to learn about each other’s lives, share resources and skills, improve conditions for farm workers, and build diverse coalitions working for social change,” according to their mission statement.

SAF’s main activity is a 10-week summer internship program which pairs college students with farmworker service agencies in North and South Carolina. SAF interns come from eight colleges and universities in the Carolinas, and from College Assistance Migrant Programs at universities in California, Oregon, Idaho, and Colorado. This summer, 10 of the 33 interns come from farmworker families.

The students work in Head Start, summer school programs, health clinics, and legal aid offices. Interns act as translators in courtrooms and clinics, organize health fairs and presentations at labor camps, and teach English as a second language and driver’s education classes.

Whether working with Mexican-American Christmas tree workers in the mountains of North Carolina or Haitian watermelon pickers in South Carolina, SAF interns provide support to understaffed agencies. In turn, they gain practical work experience.

Alma Rojas, an intern at Tri-County Community Health Center in Newton Grove, North Carolina, says doing health screenings at labor camps has helped prepare her for a career in nursing. Having grown up working in the fields herself, she also had “an opportunity to go back and help the people I used to be part of.”

For other interns, SAF provides a glimpse at an often-invisible population. Through her advocacy work with the Farmworker’s Project in Benson, North Carolina, Amy Fauver, a recent graduate of Duke University, says, “I’ve learned how many people in this country live the lives they do at the expense of the people who do the work.”

It is SAF’s goal to inspire such insights. They hope to go beyond providing services to educating the broader community about the human side of agribusiness. “We are educating the next generation of farmworker advocates,” says executive director Margaret Horn.

The experience even inspires some interns to rethink their career plans. Before working with South Carolina Migrant Health this summer, University of South Carolina-Columbia senior Fred Ortmann planned to pursue a career in a specialized field of medicine. “After this summer,” he says, “I’d like to stay in rural health care.”

The GAO also found that all pesticide illness reports, except for California’s, were limited in scope, detail, and quality of information. The study concluded that there was no way to determine accurately the national incidence or prevalence of pesticide illness in the farm sector.

Inspectors are unlikely to get even a chance to look for children working illegally on a farm. According to a provision in the annual appropriations bill, the U.S. Department of Labor prevents OSHA from inspecting farms who claim less than 11 workers. The provision is supposed to protect small family farms from regulations that apply to corporate agribusiness. But giant farms circumvent inspection by hiring contractors to provide labor instead of hiring workers directly. “The farm labor contractor is the only one that shows up on the books as an employee,” said farm worker activist Mull, “giving the farm only one worker on its books. Therefore these big farms that can have as many as 50 or 60 workers are exempt from inspection, and the farm escapes responsibility for complying with the labor laws.”

A farm owner can also record only one person on the books when in reality an entire family, including the children, could be working under that one person’s social security number.

“If we had better data and could flesh out the number of kids actually working legally and illegally, as well as those injured and killed, we might be able to raise the awareness of the public and Congress and get something done,” said the GAO’s Jeszeck. He advocates a centralized national data collection system.

Catherine A. Belter of the National Parent Teacher Association is more emphatic. Testifying before a congressional hearing in February, Belter warned legislators of the immediate need for a comprehensive data collection system for working children in order to form a strategy of prevention. “Until the U.S. has an accurate number of child[work]-related injuries and fatalities, finding the appropriate statutory or regulatory policy that will protect youth is impossible,” Belter said. “America must do a better job than continuing to take a patchwork approach to developing and amending child labor laws and regulations.”

Enforcement Blues

Getting a national data collection system in place is just part of the solution to protecting young people in the workplace, advocates say. “Enforcement is a major problem,” said Linda Golodner, executive director of the National Consumers League and co-chair of the Child Labor Coalition.

Few states have full-time child labor inspectors, and in Georgia and Alabama, laws prohibit agencies from assessing fines even when they do find children working in violation of the law. Mississippi has no labor department and Maryland has no child labor enforcement division. But even when agencies have the ability to assess fines, the penalties are rarely significant enough to deter repeat violations. In South Carolina, the fine for violating the state child labor law is $50. In Florida, the state agency can only issue a warning for the first violation regardless of the severity of the injury that may result — including death.

Further problems arise as local departments cut back on enforcement due to budget constraints. They turn over enforcement to the federal government, but a shrinking budget is causing cuts in enforcement by the U.S. Department of Labor as well.

The number of Department of Labor inspectors has dropped from 989 in 1991 to 791 in 1994, and the department has no full-time investigators assigned exclusively to child labor. Investigators in the Wage and Hour Division enforce 96 laws and regulations, including child labor, said Bob Cuccia of the Department of Labor. “Child labor is one of our major focuses,” he added. But a GAO study in 1990 found that investigators spend only about 5 percent of their time on child labor.

Nationally, recorded child labor violations dropped from a high of nearly 40,000 in 1990 to just over 8,000 in 1994. Cuccia attributes the decline to the 1991 crackdown called “Operation Childwatch” and to “education and outreach to businesses from the Department of Labor.” While child labor violations did decrease tremendously, inspections also decreased by two thirds. In 1990 the department conducted 5,889 inspections, fining businesses a total of $8,451,268. In 1994 the number of inspections dropped to just over 2,000.

“Businesses don’t worry about being inspected unless there’s some horrible incident,” said Darlene Adkins, coordinator of the Child Labor Coalition. “I’m not saying that anyone wants to harm children. It’s just that child labor laws aren’t a priority for most businesses.” A 1992 report from the National Safe Workplace Institute bears out Adkins’ observations. The report found that the average business could expect to be inspected once every 50 years or so by the wage and hour division. According to the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, it would take the Occupational Safety and Health Administration 23 years just to inspect all high-risk workplaces, including those where youth work.

Even when companies are inspected and violations are found, the maximum penalty of $10,000 per violation is rarely enforced. A prime example is Food Lion, the supermarket chain based in Salisbury, North Carolina. In 1992, the company agreed to settle charges of 1,436 child labor violations with the Department of Labor. Most of the violations, according to the company’s 10K form filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, were for allowing employees under the age of 18 to operate balers — machines that compress cardboard boxes that are rated as too hazardous for minors to use. Food Lion paid an estimated $1,000,000 for the violations. The fines amounted to $714 per violation — far below the federal maximum.

“If Food Lion had paid the maximum amount, the fines would have totaled over $ 14 million,” said Darlene Adkins of the Child Labor Coalition.

Kids Sewing and Sowing

While restaurants and supermarket chains, two industries that employ large numbers of youth, have been scrutinized by state and federal regulators over the past several years, little attention has been given to the garment and the agricultural industry. “These industries are where you find the most vulnerable kids,” said Linda Golodner of the National Consumers League. In Florida and Texas, many kids still work in “sweatshop” conditions reminiscent of the 1920s.

An investigation by the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel found that the $1.2 billion garment industry in Dade County, Florida, the nation’s third largest garment center, is riddled with flagrant violations that go virtually unpunished by the government.

Jorge Rivero, Miami district director of the U.S. Department of Labor, concedes that children are working in the garment industry. But unless inspectors catch a child at work or someone admits that children are working in the industry, there is little that can be done, he said. Many garment workers are contracted by manufacturers and work at home where their kids help.

“We’ve never had any success in fining the garment industry,” Rivero said. “I don’t know why it’s so hard, but it is. We go out every year and do directed investigations, basically at random, without [waiting for] complaints. We’ve done this for the last 30 years. It’s unusual to get a complaint.”

State officials, Rivero said, have limited resources and in most cases turn over enforcement to the federal Department of Labor, which lacks the manpower to make a dent in the illegal employment of children.

“Many employers in Dade County have no fear of the Labor Department enforcement efforts,” an International Ladies Garment Workers Union representative testified at a 1989 hearing. “They’re not hiding.”

Labor officials in the state of Texas experience similar problems. In the Dallas/Fort Worth area, officials estimate that 8,000 to 40,000 Asian immigrants are employed by the garment industry. Most work at home where children sometimes work alongside their parents late into the night. As in Florida, the state labor department has little success in curbing such violations because of lack of personnel. Recent Asian immigrants may have little choice in letting their children work and, would be unlikely to report violations. One Asian-American garment worker believes it is simply tradition in Asian families. “The family works together like always. Just like on the farm, the whole family, including the children, work.”

Jeffrey Newman of the National Child Labor Committee disagrees. “Whenever you see a child working in the garment industry under sweatshop conditions, it is exploitation,” he said.

Though legislation and enforcement in the garment industry are weak, children working in agriculture receive even less protection. Most states exempt agriculture from child labor laws altogether. And on the federal level, various exemptions in the labor laws allow farm children to work at much younger ages than in other industries.

For example, 16 and 17-year-olds can do hazardous work in agriculture, while the age for similar work in other industries is 18. Ten- and 11-year-olds can be employed if the farmer gets a waiver from the Department of Labor, simply by proving that not employing 10- and 11- year-olds would cause severe economic hardship to the farm.

How can farming be so loosely regulated when the National Safety Council has defined agriculture as the most dangerous occupation, behind construction? The answer lies in the history of the FLSA. “The FLSA was a piece of New Deal legislation that had to appeal to Southern Dixiecrats,” said Elaine Broward, a labor historian at Harvard University. At that time, farming was the lifeblood of the Southern economy. More than half the population lived on farms, and youth regularly worked. But recent changes in agricultural production have radically altered the industry. It is no longer a small-time activity. “In 1938 the dangers of agriculture were not as well-known as they are now,” said Cynthia Schneider, staff attorney with the Migrant Legal Program in Washington, D.C. “The use of pesticides and the type of farm equipment used today make agriculture more dangerous than it ever was.”

In North Carolina, state labor department officials made similar observations after reviewing a 1993 study by Kathleen Dunn and Carolyn Runyan. They found that 71 people age 11 to 19 were fatally injured while working on the job between 1980 and 1990. Twenty-seven percent of those who died were involved in farm activities. After a review of state policies, Tom Harris, director of the state wage and hour division, asked federal officials to add provisions to current child labor laws barring work in hazardous activities. Harris also recommended the exemptions for children in agriculture be repealed.

“From a safety standpoint, there is no reason today for a farm/non-farm dichotomy in our child labor laws and regulations,” Harris said.

Family Values: Get to Work!

The traditional American belief in the value of children working presents another obstacle to reforms suggested by Harris and others. Medical historian David Rosner of Baruch College in New York said that child labor has a long history that complicates attempts to restrict or regulate it. “We have deep-seated social and cultural values that play against serious attempts at protecting kids,” Rosner said. “Americans are deeply ambivalent about child labor,” he said. “We see work as redemptive and as a morally legitimate method of self-improvement.”

Indeed, beliefs about the value of work permeate the American psyche. In 1925 the National Industrial Conference Board of the U.S. National Association of Manufacturers claimed that working as a child was “desirable and necessary for complete education and maturity . . . as well as for the promotion of good citizenship and the social and economic welfare.”

More recently, according to professor Dario Menateau of the University of Minnesota, groups such as the President’s Science Advisory Committee in 1973, the National Panel on High School and Adolescent Education in 1976, and the Carnegie Council in 1979 have all asserted that work can contribute to adolescent learning of socially accepted norms, values, and behaviors. “Working during the teen years is usually seen by these groups as a helpful medium available in modern society that facilitates the transition to adult life,” Menateau said.

The myth is that these kids have to work to help support their families, said Linda Golodner of the National Consumers League. “Very, very few work to help their families,” she said. “They’re getting money to buy concert tickets, designer sneakers, cars, and things like that. We feel that it’s OK [for them] to have a job, just so that their hours are limited and they’re not sacrificing these educational years or their childhood.” While it may be true that most children work for their own spending money, in agriculture it is a different story.

Diana Mull of the Association of Farmworkers Opportunities Programs said, “The myth is that in agriculture, children are simply doing chores and that they are helping out the family. For most of the work being done in agriculture, the wages are so low that everyone [in a family] has to work just to make ends meet. One should wonder how this in any way teaches kids the value of a dollar or work when they see their parents eking out a meager living moving from place to place. How to be exploited, how to be abused, that’s something we want to teach kids, right?”

So what skills and responsibilities do kids learn at work? It depends on the job, experts say. In a 1992 study of learning in the workplace, researchers Ellen Greenberger and Laurence Steinberg observed that, “The typical jobs available to youth do little to inspire a high degree of commitment and concern.”

The authors said that jobs for most youth do not require use of even the most basic academic skills. Food service workers, manual laborers, and cleaners spend an average of 2 percent or less of their time at work reading, writing, or doing arithmetic. Cleaning, carrying and moving objects from one place to another take up between 14 and 55 percent of the time of the average food service or retail sales job. “Adolescents . . . had few illusions about the degree of expertise their work called for,” Greenberger and Steinberg concluded. “Nearly half felt that a grade-school education or less would suffice to enable them to perform their jobs.”

Quality of work may be low, but quantity of work can be too high. Another study found that students who work more than 20 hours a week were less likely to do homework, earn A’s, or take college preparatory courses. “While the drop in grades may be unimportant to a 4.0 student, for the marginal student it could be significant,” said Maribeth Oaks of the National Parent Teacher Association.

Professor Menateau, who has studied working children for more than 20 years, said schools have changed their curricula to accommodate work. “I’d hate to say that education is being watered down,” he said, “but the schools are adjusting. They simply aren’t demanding the amounts of homework and the academics that they used to because students are doing so many other things.”

Follow the Money

If lack of data, lax enforcement, and deep-seated beliefs hamper efforts to reform child labor laws, lobbying efforts by various business trade organizations make reform nearly impossible. In 1992, when former Senator Howard Metzenbaum introduced legislation to establish a national work permit system and national standards for reporting injuries suffered by minors, pressure from the restaurant industry successfully killed the measure in committee.

Likewise, when the House Judiciary Committee considered child labor laws that would have subjected employers to a $250,000 fine and imprisonment for violations that resulted in serious injury to minors, a lobbying campaign from the restaurant industry again killed the bill in committee.

The restaurant industry has good reason to fear changes in the child labor laws. According to Restaurant Business, an industry trade publication, the nation’s 400,000 restaurants employed over 1 million teenagers age 16 to 19 in 1993. The National Restaurant Association — Washington’s other NRA — a trade organization of 200,000 restaurants and proprietors, has quietly managed to prevent any changes in the nation’s child labor laws. And with a Republican Congressional majority receptive to its agenda, the NRA seems poised to weaken existing laws.

The NRA is not alone. The Food Marketing Institute (FMI) has lobbied against strengthening child labor provisions in the FLSA. Representing the nation’s supermarket chains and other food stores, FMI earlier this year lobbied to repeal a section of the FLSA that prohibits children under the age of 18 from operating cardboard compactors and balers. Bills to repeal the ban were introduced in both the House and the Senate.

The FMI may prevail despite testimony from child labor advocates, a NIOSH report that found 50 accidents as a result of operating balers, and support for the ban from Department of Labor officials. Supporters of the repeal on balers call it “a chance to create summer jobs in your district without spending a dime of taxpayer’s money,” as they wrote in a joint letter to potential sponsors. Repealing the baler ban would entice more supermarkets to hire young people without fear of being charged a penalty for letting kids throw boxes into the machines.

Supporters of the ban are stunned by the relative ease the FMI has had in pushing its baler repeal. “We have simply been reduced to commenting on the proposed changes,” said Debbie Berkowitz of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, who is urging Congress to maintain the ban.

In the nation’s capital, money talks, and both the NRA and FMI have talked generously to potential supporters of their agenda. According to the Center For Responsive Politics, the NRA gave a total of $658,844 to 279 candidates in the 1994 election, making it one of the 50 largest PACs in the country. The NRA gave 73 percent of its contributions to Republican candidates, mostly to the U.S. House. Senators received larger amounts on average — $5,089 compared to $2,057 for House members.

In 1994 the FMI gave $452,465, with more than 68 percent going to Republican candidates. More than 70 percent of the FMI contributions went to House members, with Senators receiving an average of larger amounts $3,061, compared to $ 1,186 for House members. Rep. Thomas Ewing (R-IL) and Sen. Larry Craig (R-ID), both sponsors of the bills to repeal the ban on balers, received contributions from the FMI.

A representative of the trade organizations denies that the contributions influence voting. “Political giving helps,” Herman Cain, chair and executive officer of Godfathers Pizza and a former president of the NRA, told the Wall Street Journal, “But it does not buy a decision. . . . The only thing it has done in many instances is give us access.”

This access has successfully stalled or killed any attempts to improve workplace protection for children. According to Federal Election Commission data gathered by the National Library on Money and Politics, members of both the House and Senate committees that oversee work-place laws have received $109,350 and $70,815 from the NRA and FMI, respectively, for 1991-1994.

House Speaker Newt Gingrich has been a favorite of both the NRA and the FMI. Since 1991 Gingrich has received over $27,000 from both PACs. He picked up another $230,000 from other PACs in the restaurant industry for his extra-curricular fundraising operations including his nationally televised college class called “Renewing America.” According to Federal Election Commission data, House Majority Leader Dick Armey (R-TX) received $6,500 and Rep. Tom DeLay (R-IL) $8,500 from the FMI and NRA combined. In total, said Common Cause, the restaurant industry has given $1.3 million to Republican candidates in recent years.

Republicans “cherish the restaurant folks for all the help that they have given the party,” Rep. Armey told the Wall Street Journal. “That puts them clearly within the favored category. You know the old adage — dance with the ones that brung you.”

Rep. Tom DeLay has taken this advice to heart. The NRA helped to plug DeLay’s run for majority whip of the House by shoring up support and campaign contributions in the Republican freshman class. Earlier this year, when DeLay pulled together a coalition of anti-regulation groups called Project Relief, the NRA was awarded one of the seats on the task force. Chaired by Bruce Gates, a lobbyist with the grocery industry which includes the FMI, Project Relief, according to its mission statement, is “committed to changing fundamentally the process by which the federal government regulates.”

If Project Relief gets its way, “past and proposed regulations governing such food industry areas as food safety, transportation, and occupational safety [including child labor laws] would be subject to much greater scrutiny,” Gates told the Progressive Grocer, a trade publication.

According to FEC data analyzed by the Environmental Working Group in Washington, D.C., the 115 PACs that make up Project Relief gave House Republicans $10.3 million in 1994. Most of Project Relief’s contributions have been bestowed upon members of the House and Senate Regulatory Task Forces, committees set up under the new Republican majority to oversee changes in regulations. On the House side, Rep. DeLay, who chairs the House Regulatory Task Force, received $38,423. In the Senate, Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX) received $331,733.

DeLay has fingered nearly 60 rules and regulations for weakening or outright abolition, including child labor restrictions, which the restaurant and grocery industries say are being imposed on them by the federal government. “We would like to give them as much flexibility as possible,” Rep. Bill Goodling (RPA), chairman of the committee in charge of overhauling child labor laws, told the Wall Street Journal.

Other plans of Project Relief are to do away with OSHA and NIOSH entirely or to reduce their functions, a move that would have a devastating effect on workplace safety as a whole and on child labor particularly.

“I’m not encouraged about activity that is being generated in the House and Senate this year,” said Linda Golodner, of the National Consumers League. “We’d love to see some action. But with the anti-regulatory attitude in the Congress, I don’t feel optimistic.”

What to Do

Action on the state level may hold more promise, Golodner said. The Child Labor Coalition is using model state legislation to push for reforms on the state level. The Coalition is urging legislators to:

♦ Provide equal protection under the child labor laws for young migrant and seasonal farm workers. This provision would set a minimum age of 14 for employment of agricultural workers, the same as for non-agricultural workers. It would also set a maximum number of work hours while school is in session and prohibit minors from working in hazardous occupations and around hazardous substances.

♦ Require work permits for all working minors that will give information on the number of youth employed and the industries employing them.

♦ Require labor education about workplace rights and responsibilities under the FLSA prior to a youth’s initial employment.

♦ Provide enhanced enforcement provisions and specific enforcement financing. Under this proposal, the state department of labor would publish and disseminate the addresses and names of each employer who had repeated and intentionally violated child labor laws and specify the type of violations. The information would be disseminated to students, parents, employers, and educators.

♦ Establish stiffer penalties for employers who are child labor violators. This provision would make anyone found repeatedly violating child labor laws ineligible for any grant, contract, or loan provided by a state agency for five years. Repeat offenders would be ineligible to employ a minor during this period. The Department of Labor would be required to disseminate a list of offenders to parents and authorities.

Several states are considering adopting all or portions of the legislation. “Just looking at the law and making a couple of regulatory changes can be helpful,” Golodner said. “Regulatory changes on the state level put the focus back on education for youth and save lives.”

Far Afield

Young migrant workers labor long and hard.

By Alex Todorovic

Alex Todorovic is associate editor with Point, a news monthly in Columbia, South Carolina.

At 19 years of age, Porfidio is accustomed to the nomadic life of a migrant worker. He has been on the migrant trail since the age of 13 when he first came to the United States, accompanied by his mother. They traveled and worked the fields together, starting in Florida and ending in the northern states by fall. In winter, they returned to their native Michoacan, one of the poorest states in Mexico.

The following year, Porfidio crossed the eastern United States by himself working in agriculture. At age 14, he was out of school and working full time. Once in a while, a contractor or farmer asked him how old he was, and his reply was always “16.”

Porfidio’s case is typical of many Mexican youths. Faced with a bleak economic outlook at home, he came to the United States in search of work. Reverend Tom Engle, of the First Presbyterian Church in Batesville, South Carolina, runs a migrant ministry program along with Sister Jean Schaeffer of the Holy Cross Catholic Church. Each year they see a handful of migrant workers who are not yet old enough to work full time. It is difficult to ascertain how many children work illegally in agriculture because nobody is much interested in finding out. But at least some young people labor in the fields.

The understaffed federal Wage and Hour Division is responsible for, among other things, enforcing child labor laws. Children may work as agricultural workers in non-hazardous jobs at the age of 12 with the written consent of their parents or together with their parents on a farm. At 14, children may work full time in non-hazardous jobs outside of school. At 16, they can perform hazardous jobs and don’t have to be in school.

“We don’t find a whole lot of (child labor) violations in agriculture. It is more common in other industries,” said Jane Carter, a supervisor at the Wage and Hour Division office in Columbia, South Carolina.

The Wage and Hour Division, like every other federal office operating on an already overstretched budget, makes priorities. In the course of investigating wage violations, illegal paycheck deductions and living conditions, investigators sometimes uncover child labor violations. Investigators generally do not visit an area unless they have received complaints about wage violations. Migrant workers and farmers generally don’t complain about working children.

South Carolina’s Office of Labor Services, under the Department of Labor, is responsible for enforcing state child labor laws in the state, but issued no citations in fiscal year 1993-94. For the most part, young agricultural workers don’t have much to fear when deciding to come to the United States in search of work. Whether stricter enforcement of laws would deter poverty-stricken children from going north in search of work is not at all clear. Yet, we must also ask ourselves what level of human sacrifice the United States is willing to tolerate to put cheap food on the table.

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.