This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Deborah Lott was shocked when she read the Ku Klux Klan flyers that had been left in the boys’ restroom at Young Junior High School in Arlington, Texas. Although poorly printed, their derogatory language and threats made clear what Lott already feared: that blacks and Jews were not welcome in the schools of suburban Dallas.

Lott and other concerned parents had been working for months to combat discrimination against minority students. Forming an organization called the Mid-Cities Community Council, they protested when administrators disciplined black students while failing to punish white students who used racial slurs such as “nigger.” They questioned why low-level and special education courses contained a disproportionately high number of minorities. And they demanded that elementary schools stop using a computer game called “Freedom!” depicting black males as cotton pickers and black females as servants. When the “slaves” are caught on screen trying to escape to the North, they are whipped and returned to their white “masters.”

Unsatisfied with the response from school officials, Lott filed a complaint with the Office of Civil Rights in Dallas. The OCR — a regional office of the Department of Education charged with enforcing federal civil rights laws in five Southern states — conducted an investigation. But when the findings were made public, Lott and other parents couldn’t believe what they were reading. Investigators confirmed that black students were disproportionately disciplined in 11 out of 12 schools, but found no “pattern of discrimination” by school officials. They also determined that the school district had satisfactorily handled the clandestine distribution of white supremacist literature by providing “sensitivity training” workshops — even though fewer than 15 parents and students had attended. In short, the OCR concluded, black students in the Arlington schools faced no racial discrimination or harassment. The file was closed.

At the same time Lott was battling officials in her school district, Frank Ditto was waging a similar protest 150 miles to the southeast in Henderson. Ditto, the president and founder of the Rusk County Concerned Citizens, also felt that black students in East Texas schools were being unfairly disciplined and shunted into low-level courses, fostering huge discrepancies in standardized test scores between black and white students. The schools had openly flouted civil rights laws for 23 years, Ditto said, despite repeated warnings from the Office of Civil Rights.

Like Lott, Ditto turned to the OCR for help, asking the office to force Henderson schools to comply with federal law. And like Lott, Ditto could not believe the results. OCR investigators once again documented the disproportionate placement of black students in low-level classes and the resulting racial gaps in performance. “In every instance,” the report stated, “black students scored significantly lower than other students in achievement and educational ability.” Yet the OCR once again concluded that the schools had not discriminated against minority students. As proof, the office cited newspaper clippings showing that the district had participated in Black History Month.

“That was the craziest thing I had ever heard,” Ditto said. “This district had continually flouted its disregard of federal law, and they let them do it. I came close to filing a personal complaint against the OCR based on their hostility toward me and my group. From the very beginning they had no interest or concern whatsoever with our situation and made no effort to expose or confront racism and discrimination in the system.”

Ditto and Lott knew that by failing to act, the OCR had effectively given schools its stamp of approval to continue discriminating against minority students. What the concerned parents didn’t know, however, is that the civil rights office itself has been accused of racial discrimination and sexual harassment for the past 15 years. Since 1980, the Department of Education has received repeated complaints that supervisors at the Dallas OCR have rejected black and Hispanic staff members for promotions, demanded sexual favors from female employees, and assigned impossible case loads to disabled workers. Employees who protest have been threatened with retaliation and physical harm. The hostility and infighting are so severe, employees say, that the office can no longer perform its duty to the public.

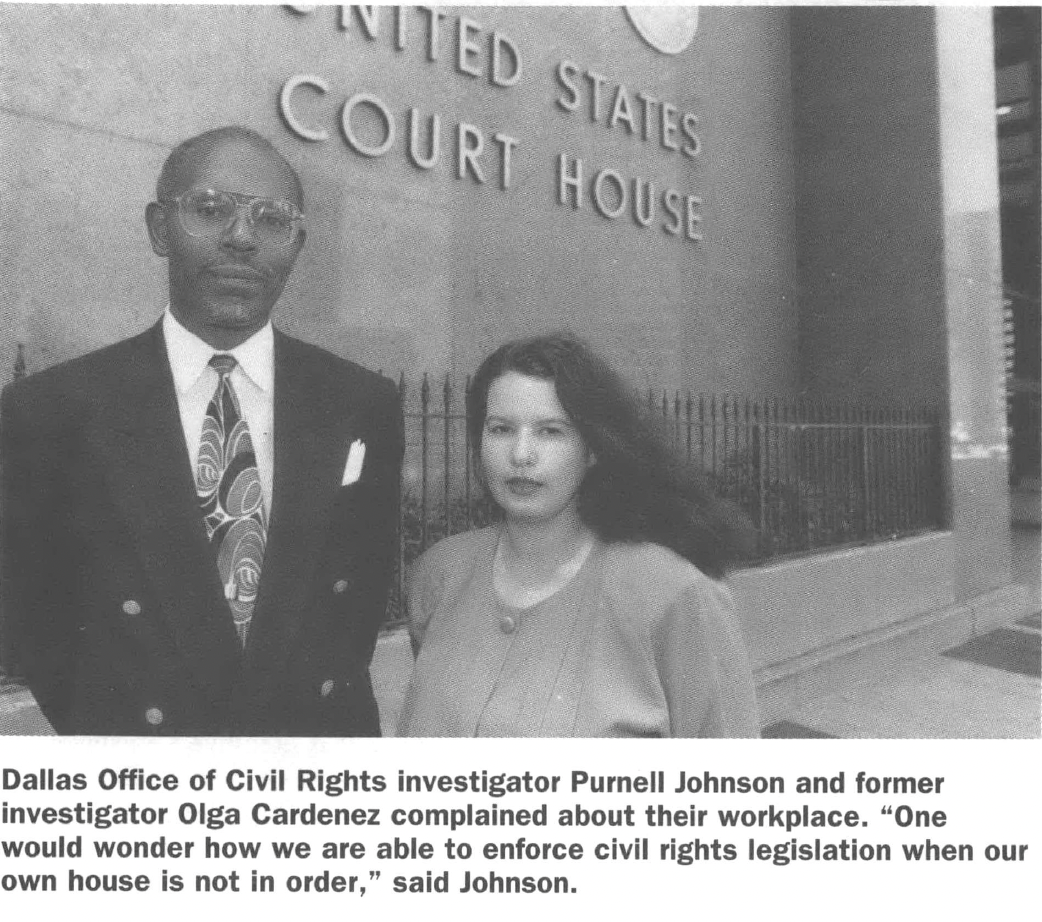

“One would wonder how we are able to enforce civil rights legislation when our own house is not in order,” Purnell Johnson, an investigator in the office, wrote to then-Education Secretary Lamar Alexander in 1992. “We consider the problems that exist within the Office for Civil Rights a moral disgrace.”

Lost Records

Alexander, who served as education secretary for two years before becoming a Republican candidate for president, took immediate action. After Johnson wrote him on behalf of a group of employees called the Equal Opportunity Alliance, Alexander sent a team of staff members from Washington to investigate. They interviewed employees and documented abuses — and then turned over their notes to Taylor August, the director of the Dallas office and target of most of the complaints. Johnson said he was told point blank he would be fired if he continued to complain.

Even before he ordered the fact-finding mission, Alexander was well aware of the problems that plagued the Dallas office. William Bennett, education secretary under Ronald Reagan, had dispatched a similar team of investigators from Washington in 1987. Dallas employees, feeling they were finally being heard, had shared their experiences of harassment, discrimination, and retaliation. Reams of information had been collected, boxed, and sent to Washington for review. Employees were later told that the material had been “lost” in transit. Bennett took no further action to address their allegations.

Employees continued to protest, however, and by 1993 they had filed so many complaints with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that officials in Washington were once again forced to investigate. Norma Cantu, assistant secretary of civil rights, contracted with the Harris Consulting Group, a Maryland-based firm, to conduct an emergency inspection.

“I was appalled by what we found,” said John Harris, who oversaw the investigation with his partner, Robert Honig. “We interviewed a majority of the employees in person. We also gave them a questionnaire to measure their stress level. We were shocked at the degree of fear and intimidation these employees felt. The women were crying, some almost hysterically.”

“There was a fear in the office,” agreed Olga Cardenez, a former OCR investigator. “Everyone was always so fearful.”

In a report submitted to Cantu, Harris and Honig concluded that the Dallas office was the most pathological work environment they had ever seen. The extraordinarily high number of civil rights complaints had virtually incapacitated the staff. Nearly half were being treated by physicians for work-related stress, and medical intervention for emotional and nervous disorders was twice the national norm. The report compared OCR employees to slaves: “Like involuntary servitude, the employee must tolerate much abuse and harm for the sake of his family and his survival.”

The report also found that Taylor August, who had been regional director since 1979, was at the heart of most of the complaints. “The workplace is one characterized by hostility in which individuals must cope by alienation, denial, isolation and anti-social responses,” the report concluded. “This workplace of hostility materializes not only in perceptions and attitudes, but in the policies and practices of management.”

A Prison Camp

Some of the worst abuses, the report noted, involved supervisors who harassed disabled employees and used their medical records “in a way that violates the Americans with Disabilities Act.” One of the employees targeted for reprisals by management was Robert Ramirez, a disabled Hispanic veteran of Vietnam who works as an investigator on the OCR staff. Ramirez had filed two complaints against Taylor August — one alleging discrimination on the basis of national origin and disability, the other citing reprisals for having filed the first complaint.

Ramirez, who injured his arm in combat and suffers from severe depression related to post-traumatic stress disorder, required a word processor and dictaphone to aid in the writing of reports, as well as job assignments that could be completed within a 40-hour work week. Instead, he was assigned extraordinary workloads with immediate deadlines — all without the aid of the equipment he needed. His own doctor and physicians at the Dallas veterans hospital agreed that work pressure was aggravating his physical disability and depression. Management asked Ramirez to present medical records documenting his need for special accommodations, and he complied.

When Harris and Honig investigated, however, Taylor August told them that Ramirez had not complied with the request for documentation. The investigators then showed August the medical information, which his own secretary had pulled from the files. The director quickly reversed himself, saying George Cole, the division director, was supposed to keep him abreast of that kind of information. Cole, when confronted, stated that he believed Ramirez was still being diagnosed and that he had not seen any documentation from the Veterans Administration.

“We can only presume that either Cole’s statement is intended to mislead or that he did not receive copies of correspondence,” the report stated, nothing that three VA physicians had diagnosed Ramirez with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. “We found Cole’s adoption of a passive role in developing an accommodation self-serving and at odds with the guidelines. We also note that Cole’s perspective, which reflected views espoused by August, effectively established a discriminatory policy against disabled employees.”

Other employees saw what was happening to Ramirez, but kept silent out of fear of reprisals. One OCR employee who asked to remain anonymous compared the atmosphere in the office to a prison concentration camp. “When the Robert Ramirezes were being metaphorically beat up by the guards, we looked the other way because we, at least, weren’t getting beat up by the guards.”

R.E. Gatewood, another disabled Vietnam veteran who worked as an investigator at the Dallas civil rights office, said the stress in the office was often overwhelming. “Just by nature of what we did — investigating civil rights abuses — the stress is high and inconsistent, like a Chinese water torture. But when you add an element of bad management, you create a powder keg.” Like Ramirez, Gatewood submitted medical records documenting his own partial disability from Agent Orange exposure and severe posttraumatic stress disorder from combat. But instead of accommodations for his disability, he received the worst performance rating of his government career.

Gatewood said the stress became so severe that he suffered a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized for 10 days. The day he returned to work, his supervisor and George Cole presented him with a memo requiring him to furnish a full medical history and asked that he adjust his therapy schedule so he could resume travel duties for the office. They also assigned him a heavier caseload and work schedule than other employees, despite letters from his doctor stating that he showed “suicidal ideation.”

On March 4, 1993, Gatewood attempted suicide. “That shook up the office,” he said. “When I came back after the suicide attempt, I made no bones about telling everyone it was the OCR that caused it. I was the poster child for stress there.”

Perhaps the most disturbing section of the Harris report recounts the death of a quadriplegic employee who was given an extensive caseload without the necessary accommodations. The employee was forced to work nights at the office and pay personal attendants to help him complete his work. “He feared losing his job,” a co-worker recalled. “That would have meant a return to Social Security disability and a return to a nursing home. For that reason, he was afraid to complain.” The employee died from a bleeding ulcer, it’s believed.

Punishing the Schools

Disabled workers aren’t the only ones who have complained of mismanagement and abuse. The Harris investigation also found that 40 percent of the female employees in the civil rights office reported experiencing sexual harassment on the job. One woman said her supervisor intentionally grabbed her breast; another reported a male co-worker who offered lewd and boisterous descriptions of his genitals. Numerous complaints involved supervisors pressing female employees for dates.

Although the Department of Education “sanitized” two pages of specific allegations when it released the report to the press, the document still contains 16 individual reports of unacceptable sexual remarks and innuendoes, and 14 independent incidents of unwanted sexual advances or touching. Management knew about the incidents of sexual harassment, the report states, and yet took no action to discipline or deter the individuals who were responsible.

Frustrated by the inaction, Veronica Davis, an OCR lawyer, filed a $7 million lawsuit last year against Education Secretary Richard Riley for incidents she alleges took place at the Dallas office. According to her suit, Davis was denied sick leave and passed over for promotion because she is black. The suit also alleges that Taylor August specifically discussed her promotion with her, seeking sexual favors in return for a better job. “It really is a case of Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill all over again,” said one investigator who asked to remain anonymous.

When Davis filed a complaint against August, the lawsuit states, she was subjected to retaliation. Supervisors monitored her phone, canceled her pre-approved leave at the last minute, and lowered her performance evaluation. According to her suit, one supervisor even hit her. When she refused to resign, she was investigated by the Inspector General for fraud. Investigators monitored her mail and credit card records and interrogated her colleagues about her comings and goings.

When employees like Davis filed complaints, supervisors also retaliated by failing to act on the cases of civil rights abuses they were documenting outside the office. “What they’d do if you filed a complaint,” said Olga Cardenez, a former investigator, “was punish you by punishing the schools you were investigating.”

Staff investigators in disfavor with management would find their reports picked to death by supervisors, Cardenez explained. “At first it would be minor changes. You’d have to go back and retype it. Then we would have to rework it to please upper management, and then legal would tear that up and make us go back to the original, first draft. It was all so trivial.”

The report by the Harris Group also concludes that the public is the ultimate victim of abuses at the Dallas civil rights office. “Professionalism and performance,” the report states, “is suborned by fear and obedience.”

“There is no doubt in my mind,” John Harris added, “no doubt at all, that the quality of the work was impaired by the work environment — one that pitted the legal department against the investigators, and managers against staffers.”

“No Violation”

The Office of Civil Rights has always had a poor record of responding to public complaints — in the Dallas region and elsewhere. During the women’s movement of the 1970s, women were filing complaint after complaint of discrimination and harassment in public schools and universities, but years often passed before the OCR bothered to investigate. Finally, the Women’s Equity Action League received a court order in 1977 instructing the Dallas office to do its job in a reasonable and timely manner.

When the court order expired in 1987, nationwide spot checks conducted by the Congressional Committee on Education and Labor found that the office was still doing an abysmal job of enforcing civil rights legislation. “OCR’s case processing statistics reveal that the agency had not vigorously enforced laws protecting the right of women and minorities in education since 1981,” the committee reported. In a significant number of complaints that were investigated between 1983 and 1988, the committee added, the OCR found “no violation” of civil rights statutes.

A recent computer analysis of OCR records revealed that the Dallas office has been even more negligent. From 1991 to 1993 the office investigated 35 school districts in North and East Texas for racial discrimination — including the complaints at Arlington and Henderson filed by Deborah Lott and Frank Ditto. In all but one case, the office concluded that no violations had occurred.

When Harris and Honig filed their final report in late 1993, they noted that the Dallas office had the worst record in the Department of Education for meeting its goals, as well as the biggest backlog of cases. The report concluded that Taylor August, who had been reassigned to Washington during the investigation, should be relieved of his duties as director.

But that’s not what happened. Shortly after the report was filed, August was reassigned to head the Dallas OCR. The move provoked an immediate outcry. Three members of the Texas congressional delegation protested to Education Secretary Riley, saying that reinstating August would have a “severely detrimental impact on the OCR.” All but 20 of 76 employees on staff signed a petition asking Riley to reconsider. When they received no response, employees picketed outside the regional office. One carried a sign that read, “Do the right thing — free our employees.” Another placard asked, “Vice President Gore, when will you reinvent the Department of Education?”

“There is great hostility in the office — there always has been,” said Robert Ramirez, the disabled veteran, who recently filed a lawsuit against the department. “But what I don’t understand is why headquarters in Washington won’t remedy the problem. This is the Office of Civil Rights. We are charged to make certain that these very types of egregious acts do not happen in schools and universities. Yet they are rampant in this very office.”

Taylor August and the Department of Education refused to comment — but employees did get a response from William Webster, chief of staff for Secretary Riley. Webster told employees that August, who is black, was reinstated after he filed his own discrimination complaint against the department. Webster assured the staff that August would be given “sensitivity training.”

Purnell Johnson and other black investigators were furious. Why, they asked, had the department acted on August’s case so quickly, while ignoring decade-old complaints by employees? In a letter to David Wilhelm, chair of the Democratic National Committee, Johnson blasted administration officials for introducing August to members of the Black Congressional Caucus as “one of the best” regional directors at OCR. “It appears that Vice President Gore’s call for the reinvention of government has fallen on deaf ears in the Department of Education,” Johnson wrote.

After investigating the department, John Harris was forced to agree. “It’s an old boy network, and very well-connected,” he said. “Basically, they circled the wagons to protect themselves because they were all involved in cover-ups in the past. And the ones who are really hurt are the citizens they are charged to protect.”

Tags

Carol Countryman

Carol Countryman is a freelance writer in Kemp, Texas. (1995)