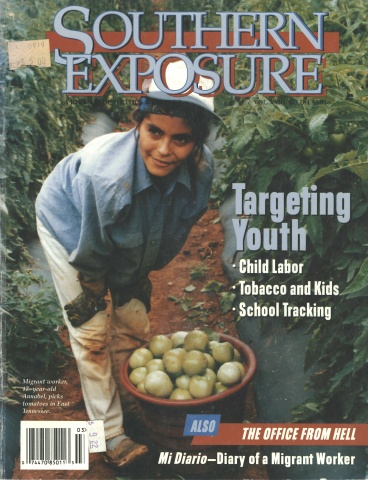

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

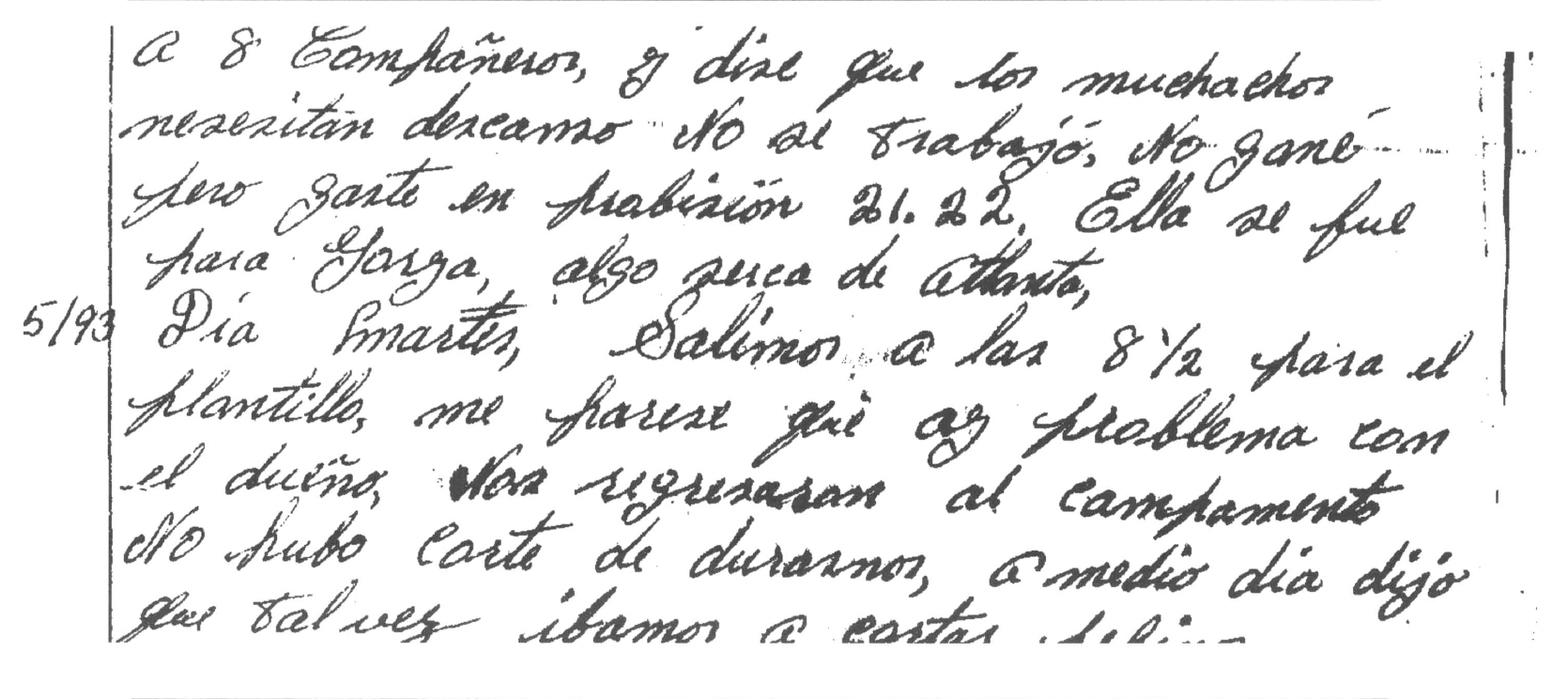

Erasmo Ramirez was born in Leon, Nicaragua, in 1932. He received little schooling, though he learned the trade of a shoemaker. He spent three years in the Sandinista army, stationed in the mountains.

With unemployment rampant in his country, Ramirez left his wife and children and came to the United States to look for work. He had heard he could make $800 a month working in the fields. I met Ramirez in 1994 while working on a story about migrant farmworkers in South Carolina.

In my research I found that conditions for migrant workers in South Carolina were deplorable. Workers were regularly cheated out of their wages. Housing and sanitation conditions were atrocious. Farmers who hired migrants had little to fear because laws designed to protect workers were not enforced. The federal Wage and Hour Division was sorely understaffed and ineffectual. The Migrant Farmworkers Commission, which was supposed to look out for the interests of the migrant farmworker, was composed of farmers and others appointed by the governor. It did not advocate for migrant laborers. The workers were left in a lawless vacuum.

The prognosis for substantive change remains bleak. Lost in South Carolina’s current legislative debates about budget cuts, nuclear waste storage, and welfare reform is the fate of the 40,000 migrant farmworkers who pass through South Carolina annually.

Anything I could ever write about the plight of migrant farmworkers pales in comparison to Ramirez’s first-person account. Excerpts from his diary offer a glimpse of day-to-day existence for migrant farmworkers.

6/5 I arrived in South Carolina at 5:30 a.m.

6/6 At 8:00, my acquaintances (from Nicaragua) took me to meet an intermediary for peach pickers. At 10:00 we left Columbia and went to a ranch called Monetta which is near a small town called Aiken. We arrived at a quarter to 12:00, and about an hour later a man showed up looking for peach pickers. Four of us went with him, three Mexicans and myself. They paid us $15 for three hours. At 6:00 the crew chief took me to a ranch where I was greeted by another contractor, Miss Maria Matto. There were approximately 30 people, all of them Mexican. They looked very humble and sad. It was a horrible moment for me to see people who had fallen so low. They were poorly dressed and some didn’t even have shoes. I wanted to maintain some dignity even though I felt sad. I tried to talk with them, but they were cold and distant. That night I didn’t sleep.

6/7 At 6:00 the boss pounded on the doors to wake us up. We had coffee and potatoes for breakfast, which weren’t appetizing. We gathered at 8:00 to go to the peach orchard. They gave us each a ladder and a cloth sack three feet tall and two feet wide. That day I filled 22 bags at 40 cents each and made $8.80. Maria has promised us free rent and food. The rooms are large, but the beds are filthy. We walk with the bags hung around our necks like horses pulling a carriage.

The yield of the peach trees is poor, and the work is deceiving. It seems that the three Mexicans have also been suckered, but they’re used to moving from one farm to the next because they’re agricultural workers. Some of them are planning to leave tomorrow morning and look for work somewhere else. I would also like to flee. I use the word flee, because I feel like a prisoner. I’m in an unfamiliar place with no phone. Mail does not exist for us.

6/8 Breakfast was the same. We began work at 8:00, and there were only nine of us left. Near lunchtime we had a small meeting and agreed to ask for a raise. A peach bag weighs about 40 pounds when it’s full. Maria offered to pay us 45 cents per bag. Today I filled 30 bags and made $13.50. Three more men left.

6/9 Maria gathered us together before we went out to pick and offered us the same amount per bag, 45 cents, but she has also offered us two dollars an hour on top of what we pick. But she will no longer provide food, and says that each one of us has to buy our own supplies and cook our own food. Today I filled 32 bags and made $14.40 plus $16 in wages for a total of $30.40. But I had to spend $10 on provisions.

6/10 I couldn’t make breakfast because we all share one kitchen and there was no time. We worked half a day because the workers refused to continue. They say they’re being robbed, and the yield of the fruit is poor.

6/11 This morning nobody wanted to work. They demanded more money, and when they didn’t receive it, they left. I didn’t want to go with them because they were going to spend all of their earnings for a bus ticket. I’m the only one left. There are 60 empty rooms and it’s absolutely silent. It looks like a deserted hospital. I don’t know what to do. I’m isolated with no telephone, no mail. I spent $9 for food and a pack of cigarettes.

6/12 Maria is worried and went to Florida to look for more workers.

6/14 Maria came back from Florida with eight men. We didn’t work today because the new workers are tired. We worked late and the yield was good, but they lowered the price from 45 cents to 40 cents, and they’re no longer paying us $2 an hour. I made $20.40. I’m beginning to realize that the figure of $800 a month, what I was told I could make, is not realistic because we are working by piece rate.

6/16 I feel sick. I have a hoarse throat. I’m thinking about my country and my bad luck. We began picking at 7:00 a.m. At 12:00 they gave us lunch and said we had to pick spinach. They offered us $5 an hour and gave us one hour free. We worked until 5:30. I returned to the cabin completely exhausted. I could hardly walk, let alone cook. The field where we picked the spinach was like a desert and, since we were receiving an hourly wage, we couldn’t take a break. It was a tough day, but I made $41.50.

6/17 We started at 7:25 and it was a hellish day. We picked spinach until 5:30. They lowered our wage to $4.25 an hour without any explanation. I made $38.25.

6/18 They woke us at 4:30 to begin work early. We were at the orchard at 6, but the yield was poor. Some of the men complained and the gringo got mad and there was a problem. We worked one hour. I made $1.60.

6/19 We didn’t work. Maria treats us like her property. The abuse is too much, but that’s the way life is out here. I’ve noticed that no gringos work in the fields, but there are some black gringos who drive tractors. The lowest level is made up of Mexicans and Haitians. They are the largest groups. There are two Nicaraguans. The other use to be a Somosan Guardia. He speaks English well.

At 7:00 in the evening, Maria told us to gather our miserable belongings, because we were leaving Monetta. It was just like being a guerilla in the mountains. She said we were going to Georgia. We arrived at this new place at midnight after a five-hour drive. I wound up in an ancient room. There are two beds, and I had the luck of getting one of them. One man got the other bed, and two had to sleep on the floor. My other co-workers got drunk all over the compound. They vomited and made asses of themselves.

My sadness is great because it seems as though I am the only one that is conscious of everything that is happening. I’ve concluded that this is a life for vagrants. Some of the men have been doing this for years. I don’t see any future in it. My room looks like it was abandoned a few months ago. There is dirt everywhere and no place to sit down. The furnishings consist of two mattresses thrown on the floor. There’s one kitchen and a bathroom with dirty pieces of cardboard that are supposed to be floor mats. It’s disgusting. There is no place to buy food anywhere in the area.

6/20 I have not had anything to eat. It is 10:00 a.m., and Maria has not appeared. There are three men in the room, three Mexicans and myself. They are all between 17 and 19 years old. I have not received any money since Friday of last week. Maria is holding it all. She told us the reason we have come to Georgia is to cut tobacco so that we can make more money.

Today was an unpleasant day. The toilet did not work, the refrigerator was useless. All I’ve eaten is corn flakes and crackers. I tried to find a phone today and finally found one miles from here. Maria came back at 5:00 with two new men. They moved me and the new guys to a place that is better, even though it’s a trailer. The room has better air conditioning. They finally took us to buy food. My spirit is revived, but I still haven’t been paid.

6/21 In the new room there are three beds, two chairs, a sofa, kitchen, table, and refrigerator. The bathroom is in good shape. At 7:00 they came to our trailer and told us that we were going to cut tobacco. Picking tobacco was not hard, but the heat was suffocating. The temperature was almost 120 degrees. They are paying us $4.25 an hour. We worked 10 hours.

My new roommates are excellent. They cook and I wash the dishes and clean the house. Maria is being stubborn about paying me. She owes me since last Friday, and here we are in a new state working for a new farmer, and she keeps saying “later.”

6/22 The tobacco fields are one hour from our residence. They picked us up today at 6:00 and we began working at 7:00. The work was the same. I worked nine and one-half hours and made $38.25.

6/23 We did the same work for 10 hours and I made $42.50. The sun and the heat make me feel like shit. One of my roommates is a drug addict. I guess I was wrong.

6/26 We didn’t work. It was a sad day for me. We didn’t cook anything. Salvador bought 30 beers and got crazy. He went to town on an old bicycle. It’s 9 p.m. and he hasn’t returned. He loses control, and I can no longer trust him. He’s too irresponsible.

6/27 Nothing unusual happened. I miss my country and am living only from memories.

7/1 Same number of hours, same work. Today Maria paid me the money she has owed me for a long time. It took a lot of effort to get her to pay me. It seems that she wanted to keep the money.

7/3 I woke up at 4:00 in the morning. Salvador wouldn’t let me sleep. He kept coming and going all night, playing music. I made chicken soup at 10:00 to recover, but unfortunately I never had a chance to eat it because Salvador gave it to one of his drug addict friends. We argued about it and I’ve decided I can’t continue living here. I left at 4:00 in the afternoon and began walking along the highway. I couldn’t make it to town, and slept on the side of the road.

After spending several months in the United States, Erasmo Ramirez, returned to Nicaragua. He rejoined his wife and children and lives in Managua.

Advocates

Dan Bautista

In 1991, under a flurry of negative publicity about migrant labor problems in South Carolina, then-Governor Carroll Campbell created a Migrant Labor Division under the Department of Labor and in conjunction with the Migrant Farmworkers Commission. The Migrant Labor Division was staffed by Dan Bautista, a Mexican-American and the first state official to identify where migrant camps were located.

Over the course of two years, Bautista informed workers of their rights as migrant laborers and helped to bring the children of resident migrant workers into school systems. He was well-liked by migrant workers. But he did not have legislative or enforcement power.

The Migrant Farmworkers Commission stymied his efforts by not taking action on his proposals, and by failing to meet a quorum for important meetings. It was up to them to request funding for the Migrant Labor Division from the governor’s office.

In 1994, when the commission failed to request support and it became clear that funds for his job would not be reinstated, Bautista resigned in protest.

— Alex Todorovic

Mary Ellen Beaver

Intrepid and tenacious, 64-year-old Mary Ellen Beaver blasts down country roads in her trusty Dodge, searching for labor camps hidden within a steamy maze of dense orchards. With a nun-like demeanor (and a medal of honor from Pope John Paul II), she apprises workers of their rights the while boldly confronting crew chiefs and farmers about the need for fair wages and improved housing.

This crusader’s resolute efforts have not gone unnoticed. In Pennsylvania, Beaver’s work led to the passage of one of the nation’s toughest farmworker laws. For the past four summers, she has been ruffling the feathers of the good ol’ boy system in South Carolina.

Due to Beaver’s obstinacy, her employer, Florida Rural Legal Services, won a landmark trespassing case giving legal aid employees the right to speak with farmworkers on private property. The case began in 1991 when Beaver drove straight past a security gate on an Okeelanta sugar cane farm. Despite the attempts of five guards to remove her, she began distributing booklets detailing workers’ rights.

In the trenches for 26 years, Beaver could easily retire on her 96-acre Pennsylvania farm surrounded by her seven children and five grandchildren. Instead, she drives the back roads of a thousand other farms, logging 40,000 miles on her car each year.

Why does she do it? “This is war,” Beaver says.

— Alice Daniel

Tags

Erasmo Ramirez

Alex Todorovic

Alex Todorovic is a translator, freelance writer, and contributor to Point, a Columbia, South Carolina, alternative paper. (1995)