This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

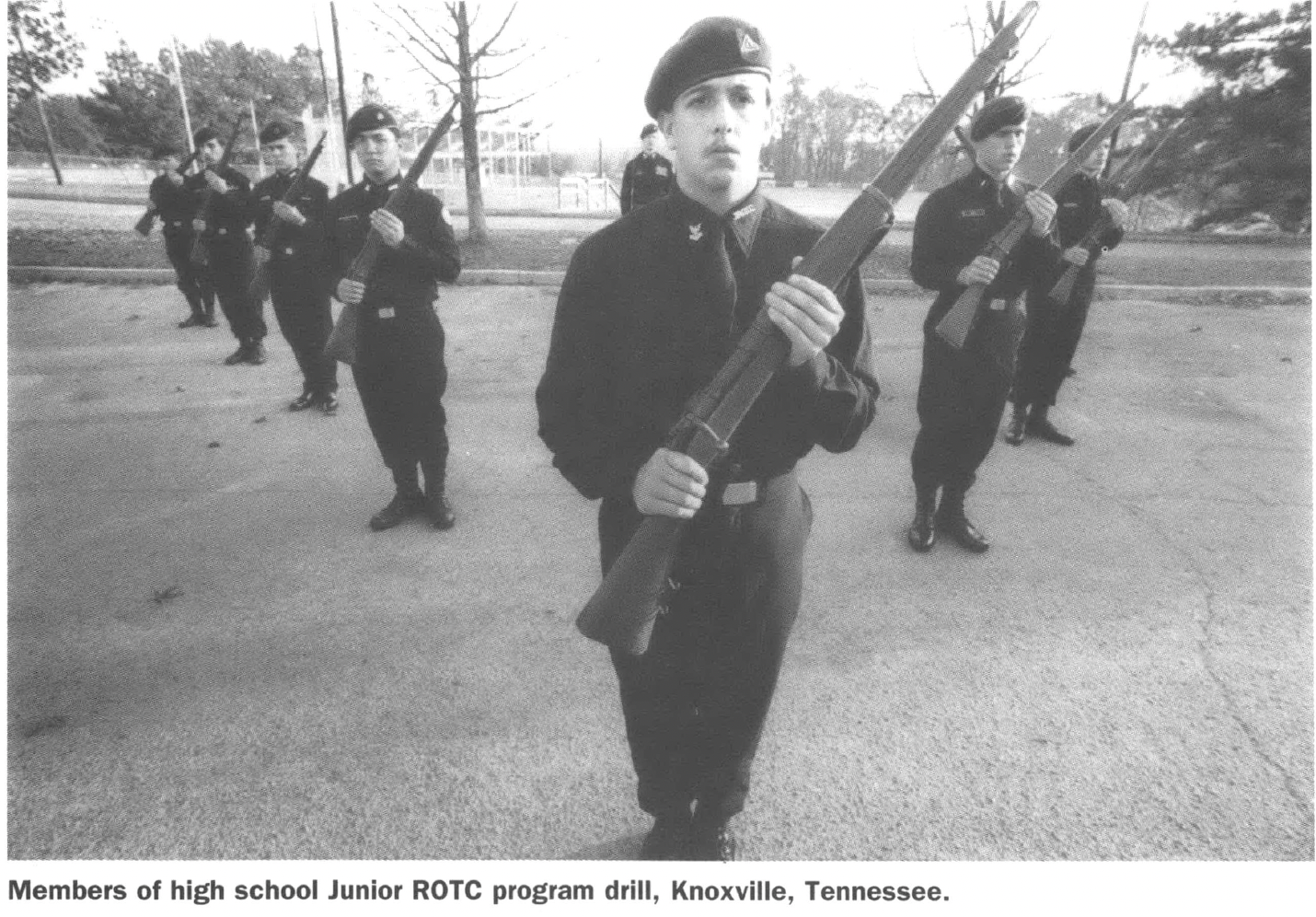

In 1916, to help the recruiting effort for World War I, Congress gave its approval for the creation of the Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps, or JROTC. In 1919, the first of these high school military education and recruitment programs opened.

Now, after a massive revitalization and expansion of the program in 1992, JROTC has taken a foothold in many of America’s poorer high schools, touted by the military as the solution for “at risk” kids. And, as a new report from the American Friends Service Committee reveals, that foothold is centered disproportionately in the South.

“[JROTC has] an easier time installing in the South,” explained Harold Jordan, coordinator of the Committee’s National Youth and Militarism Program. The military, and consequently JROTC, “has a uniquely strong basis of political and institutional support in the South. It’s part of the establishment,” Jordan said in an interview. He was a researcher for the report.

As the Committee’s report, “Making Soldiers in the Public Schools,” points out, JROTC programs tend to be aimed at poor kids in poor districts, and draw disproportionately from the black community.

The South, then, which hosts numerous military bases and has a history of under-funded education, seems fertile ground for JROTC programs that promise to bring federal money and give students discipline and opportunities. And, as the report reveals, nearly 65 percent of the nation’s 1,982 JROTC programs are located in the South.

“JROTC rarely is found in suburban high schools that have high rates of college-bound students, and still less frequently in affluent schools with a substantial white population,” Colman McCarthy wrote in a Washington Post op-ed piece. “JROTC might as well be called Operation Poor Kids. With Congress giving money to the Pentagon for JROTC, the ruling class pays the warrior class to recruit from the lower class.”

In New Orleans, for example, one of the nation’s poorest cities, every school district has applied for a JROTC program, and military officials are beating down their doors, the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported.

Does JROTC follow through on its promises? In many ways, the report contends, it does not. First of all, while JROTC programs bring some Pentagon dollars, local school districts are expected to foot a large portion of the bill, often a quarter of a million dollars or more.

In Brownsville, Texas, according to the Brownsville Herald, the school district paid $328,562 of the $455,249 JROTC bill for the 1991-92 school year. That’s not including an extra $312,000 the district spent on new facilities for the program.

In struggling districts, that money often comes at the expense of other academic and support programs.

Furthermore, the Committee argues, the JROTC academic curriculum is heavily propagandized, avoids controversial issues, and generally is not held up to the same standards as traditional curricula.

The report also points out that there is no evidence to suggest that JROTC programs reduce dropout rates, increase college admissions, or better a student’s vocational future — except in the military (45 percent of JROTC graduates do go on to some sector of the armed services).

“My fear is that students are being channeled into the military, as opposed to being given a quality education,” Jordan said. That fear is compounded in the South, he said, where heavy support for the military can make it harder for young people to resist the draw of a JROTC uniform. “Districts have a responsibility to ask that kind of question and demand accountability [from JROTC].”

But, Jordan said, school districts he looked at didn’t ask those questions, and took JROTC and its promises at face value. “JROTC is a false guide. And as we know, when times are tough, people turn to false guides.”

Tags

Sam Greene

Sam Greene is a sophomore in the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. He lives in Durham, North Carolina. (1995)