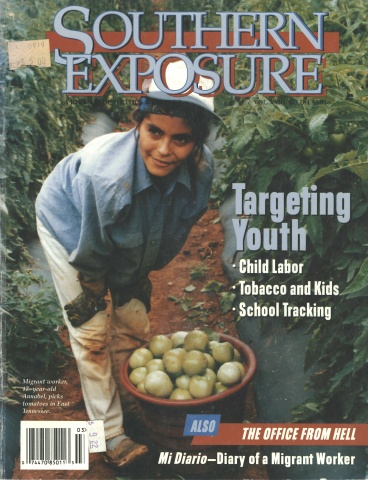

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

Fourteen-year-old Erica Rolls had no intention of becoming an activist. “I had a classroom assignment to find a newspaper article dealing with teen issues,” Rolls said. After thumbing through the papers at school, she saw an article that caught her eye. “I found one about the American Lung Association making grants available to eight Kentucky schools for tobacco control,” Rolls said. “I ran to the phone to call them and apply.”

Rolls, who lost all of her grandparents to tobacco-related illness, was eager to do something to educate her peers on the dangers of smoking. “I’m not anti-tobacco,” she said. “I have respect for adults who want to smoke, but I want the kids to know what tobacco does before they start.”

With the grant from the American Lung Association in 1994, Rolls founded Kentucky Youth for Healthy Futures at her high school. The organization is affiliated with Smokeless States, a national group based in Chicago that encourages youth groups to do peer education on tobacco through grants from the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation.

The students organize store “buys” of tobacco, in which children attempt (often successfully) to purchase tobacco. They conduct these projects to show just how accessible tobacco is to young people, even though it is illegal to sell to them. The group also made a commercial with junior high students. “The only flak we’ve had has been from some principals,” Rolls said. “They are afraid that local stores which donate to the schools would stop.”

Rolls’ concerns about tobacco use and youth have merit. According to government studies, every day 3,000 adolescents in the United States begin to use tobacco.

An Institute for Medicine report found minors consume at least 516 million packs of cigarettes per year, and at least half of those are illegally sold to minors. The National Cancer Institute estimates that at current teen smoking rates, five million American adults who began smoking as adolescents will die prematurely.

“The earlier young people begin using tobacco, the more heavily they are likely to use it as adults,” wrote Philip Lee, of the Public Health Service, and David Satcher, of the Centers for Disease Control, in the 1994 Surgeon General’s Report on tobacco. “Preventing smoking and smokeless tobacco use among young people is critical to ending the epidemic of tobacco use in the United States.”

Curbing Access

Attempts to curb the sale of tobacco products to kids began at the turn of the 20th century. Reformers who were concerned about the demoralizing effects of tobacco on young people pushed state governments to enact laws prohibiting sales to persons younger than 18 years old. The laws, however, were rarely enforced. By the mid-1940s, the tobacco industry’s political and economic clout caused several states to begin dismantling their laws altogether.

Despite the recent focus on smoking as a health problem and tobacco’s appeal to teenagers, attitudes remain lax. In 1990, the Office of the Inspector General reported that though 44 states had youth access laws, none were effectively enforcing them. In 1992, the Department of Health and Human Services found that although all states prohibited the sale of tobacco to minors, only two states enforced their access laws.

The Secretary of Health and Human Services estimates that three-fourths of the approximately one million tobacco outlets in the United States sell to minors, garnering over one billion dollars each year. The Surgeon General’s office, in 13 studies of over-the-counter sales, found that 32 to 87 percent of minors were able to purchase tobacco products, mostly at small convenience stores, gas stations, or supermarket chains.

“The merchants don’t really care, as long as they get their money,” said Tierney Brown, a 14-year-old tobacco control activist from Greensboro, North Carolina.

In the absence of access law enforcement, several organizations have conducted their own campaign to curb teen smoking.

One such group, INFACT, a nonprofit organization based in Boston, began its activist work in 1977 by organizing a boycott against Nestle. That company was marketing infant formula to Third World countries that could ill afford it. INFACT won an Academy Award in 1992 for its documentary Deadly Deception, an expose of General Electric and the nuclear weapons industry.

In May 1993, INFACT launched its campaign against tobacco companies that target children. Earlier this year, members held a demonstration outside the entrance to Philip Morris’ Richmond, Virginia, plant where board members were holding their annual meeting. INFACT members stood outside holding a 150-foot-long banner decorated with photos of people who have died or are suffering from tobacco-related illness.

Kathy Mulvey, campaign development director for INFACT, participated in the demonstration from the inside. Philip Morris allowed Mulvey to speak for two minutes to the more than 700 stockholders, board members, and managers. Other demonstrators inside held up large photographs of people who had died from tobacco use. “We wanted to escalate tensions inside the company,” she said. “We confronted shareholders with the human toll of tobacco.”

INFACT is soliciting more photographs of anyone who has died or is suffering from a tobacco-related illness to be used in other protests. One such photo shows Tony Nicholson, of Andover, Massachusetts, with his wife and two of his three children. Nicholson died at 37 from lung cancer. He had begun smoking at age 14, according to INFACT.

Easy to Buy

The American Stop Smoking Intervention Study (ASSIST) is a partnership between the National Cancer Institute and the American Cancer Society. ASSIST works with local health departments and volunteer organizations to develop and strengthen tobacco use prevention programs in 17 states, including West Virginia, Virginia, and the Carolinas.

The group launched a campaign to test the ability of youth to purchase cigarettes. A series of buys completed in 1994 by the group in North Carolina showed that youths ages 11 to 17 could buy tobacco half of the time from retail stores and 91 percent of the time from vending machines. To publicize the result of the campaign, ASSIST arranged for children to visit the state legislature to talk about their experience.

Tierney Brown, who is also a member of North Carolina ASSIST, got involved in the organization through her mother, who had picked up an information packet about the organization. “I didn’t know it was that easy to buy cigarettes,” she said, after reading about the buys. Looking through the information her mother had given her, she said, “I wanted to find out more about ASSIST. I think kids are more effective in getting the message through. They are more willing to listen to someone their age.”

Project HUSH, an organization based in Greensboro, North Carolina, also uses buying operations to get its anti-smoking message across. Member LaShonda English says that Project HUSH does not report the stores it catches selling cigarettes to minors.

“Instead, we go back to the stores and hand out information, stickers, and posters so that customers can be informed,” she said. “Most merchants follow the laws.”

English joined Project HUSH because she didn’t like to see kids her age smoking. “It’s not good for your health,” she said. “It could mean a shorter life.”

Despite the efforts of these groups, some youths continue to smoke. David Dubner, president and founder of the only youth-run anti-tobacco organization, Student Coalition Against Tobacco (SCAT), says youth either subscribe to the “invincible theory — it won’t happen to me — or just don’t care.”

Dubner said his group tries to reach other youth through peer education. High school students create and perform skits for local elementary school students. The skits teach kids how they are targeted by the industry and a little bit about the health aspects of smoking, he said.

“We try to change attitudes, like what Students Against Drunk Driving has done for drunk driving — it’s not cool, not everyone is doing it,” said Dubner.

Money and Politics

Tobacco means big money, and the industry spreads its wealth generously among politicians. When a measure that would have strengthened laws prohibiting sales of tobacco to minors was proposed last year, the new Republican majority in the U.S. Congress pushed for a six-month moratorium on all new federal regulations, effectively killing the bill. When Republican Congressional Representative Thomas Bliley of Virginia took over as chair of the Health and Environment Subcommittee, he vowed to end the Congressional investigation of the tobacco industry that had taken place under Democrats. “I don't think we need any more legislation regulating tobacco,” Bliley said in an interview. Bliley has received $111,476 from tobacco-related interests since 1985.

He is not alone. According to an investigation by Common Cause magazine, tobacco industry PACs have poured more than half a million dollars into the campaign coffers of 18 of the 26 members of the subcommittee on health and environment. From 1989-1994, 73 percent of all senators accepted campaign contributions from the industry; in the last House election cycle, 66 percent of the House members took tobacco money. Since 1985, the industry has contributed more than $16.6 million to federal candidates, PACs, and political party committees. Southern legislators were the primary beneficiaries of tobacco PAC money.

House Speaker Newt Gingrich, the man behind the recent Republican takeover of Congress, has been known to travel in an RJR Nabisco jet, according to Common Cause. RJR Nabisco is a food conglomerate and one of the top cigarette manufacturers in the world. Gingrich has received $41,000 in campaign contributions from the tobacco industry since 1985. RJR Nabisco has contributed at least $50,000 to GOPAC, a Republican political action committee that, until recently, Gingrich headed.

As eager as the industry is to reward those who support its policies, it is just as eager to punish those who oppose them. Oklahoma Democrat Mike Synar, a key anti-tobacco legislator, lost his House reelection bid last year. The tobacco industry heavily supported his opponent.

The tobacco industry also exerts influence on the state level. In June, a bill was introduced in the North Carolina legislature requiring schools to teach character to elementary school students. The curriculum would include information about the health risks of premarital sex, drugs, alcohol, and tobacco. Rep. Lyons Gray, a Winston-Salem Republican whose family once ran the tobacco company RJ Reynolds, drafted an amendment deleting tobacco as a health risk. The amendment passed easily.

Alexander “Sandy” Sands III, a former North Carolina state legislator and lobbyist for the tobacco industry, defended Gray’s position, saying, “Despite what people say, tobacco is not the worst evil in the world today.”

The industry supported a North Carolina bill which says that a merchant, in order to be held accountable, must “knowingly” sell tobacco to a minor. The minor can be charged a $100 fine. The bill prevents local communities from making stronger laws (except in the case of vending machines). It also prevents “buys” by any group to check on compliance.

This bill, according to Mary Gillett, Project ASSIST coordinator, will penalize minors instead of merchants for buying cigarettes. “It will also make it illegal for groups like HUSH to conduct buying operations,” said Gillett.

In response to harsh national criticism, the tobacco industry has decided to take action. According to a recent USA Today article, Philip Morris has unveiled its own program aimed at keeping kids from obtaining cigarettes. The program, referred to as “Action Against Access,” includes banning free cigarette samples, penalizing merchants fined or convicted of selling cigarettes to minors, and supporting “reasonable” requirements that merchants obtain licenses to sell tobacco.

In a series of full-page newspaper and magazine advertisements across the country, RJ Reynolds, now a subsidiary of RJR Nabisco, said two of its own programs have been effective in educating kids about the dangers of smoking. According to the ads, the program has been sent out to thousands of retail outlets and high schools, reaching over 3.3 million students.

Some critics charge the companies with waging a public relations battle while continuing to target their products to children. INFACT found that for nearly 40 years the Council for Tobacco Research (CTR), an industry-sponsored research group, has conducted what the Wall Street Journal called “the longest running misinformation business campaign in history.” Portrayed as an independent scientific agency to examine “all phases of tobacco use and health,” the CTR has actually been the centerpiece of a massive industry effort to cast doubt on the links between smoking and disease.

Dorothea Cohen, who worked at CTR for 24 years until her retirement in 1989, refuted the CTR’s role as a purely research organization. “When CTR researchers found out that cigarettes were bad, [that] it was better not to smoke, we didn’t publicize that,” she said. “The CTR is just a lobbying thing. We were lobbying for cigarettes.”

Peggy Carter, spokesperson for RJR, dismisses accusations that the tobacco industry targets kids. “We absolutely do not target children,” she said. “Our market is adult smokers only. Our promos are limited to ages 21 and over, and we voluntarily place our billboards at least 500 feet from where children congregate.”

However, at least one tobacco company has studied children and tobacco. Rep. Henry Waxman, a Democrat from California, recently opened to Congress secret research documents from Philip Morris, according to Associated Press. These documents showed that Philip Morris studied hyperactive third-graders in 1974 to see if, as teenagers, they would smoke to calm themselves, “show[ing] that smoking is an advantage to at least one subgroup of the population.” Another study of college students in 1969 used electric shocks to see if the subjects smoked more under stress. “These documents make it crystal clear that we need regulation of tobacco to protect our children from becoming addicted to a life-threatening drug,” said Waxman.

Selling the Smokes

No brand has been more controversial than Camel cigarettes and its Joe Camel character. Launched by RJ Reynolds in 1988, Joe is modeled after many of the “cool” characters seen in movies and television. Since his first appearance, sales of Camel cigarettes have increased from $6 million in 1988 to $12 million in 1991 among 12- to 19-year-olds, according to ASSIST.

A survey in the 1994 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report, Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People, found that 73 percent of kids age 10-17 recognized Joe and 81 percent of those who recognized him knew he was the symbol for Camel Cigarettes. In a survey by BKG Youth for Advertising Age, 90 percent of 8- to 13-year-olds named Camel as a familiar cigarette brand; 73 percent named Marlboro.

About four percent said they had already tried cigarettes at least once. Regardless of industry protest that advertising doesn’t directly correlate to use, the top three brands among smoking youth — Marlboro, Camel, and Newport — are also the most heavily advertised, according to Project ASSIST.

The Federal Trade Commission began an investigation in 1991 of the Joe Camel campaign, and after three years, by a vote of 3-2, found no evidence that RJR targeted youth. The majority of the Commission issued a statement saying, “While it may seem intuitive to some that the Joe Camel advertising campaign would lead more children to smoke or lead children to smoke more, the evidence to support that intuition is not there.”

A California study in The Journal of the American Medical Association in 1991, however, showed that the brand is much more noticed among children and adolescents than among adults and that the percentage of youth who smoke Camels is twice the percentage of adults.

“Joe Camel is just a convenient vehicle for the total advertising ban such anti-tobacco groups want,” said Carter, referring to such studies.

Youth are also influenced by celebrities whom they see smoking. “Youth see many of the 20-something stars such as Johnny Depp, Madonna, Brad Pitt, and Winona Ryder smoking prominently, either in films or in their private lives,” said Michael Erickson of the Office on Smoking and Health at the Centers for Disease Control. Tobacco companies also sponsor sporting events such as car racing and baseball, which many children attend.

Kelly Louallier, campaign director for INFACT, says that advertisers, through their use of cigarette emblems on T-shirts and other clothing, are “trying to turn our children into human billboards.”

Louallier doesn’t believe the industry is sincere in its recent efforts to prevent youth from smoking. She says the industry targets youth: “Absolutely,” she said. “It’s the key to their future success. The industry would have to go away [without young smokers] because they wouldn’t have any customers.”

Louallier says youth should understand three things about the tobacco industry: “The tobacco companies are lying to you. All they want is your money. Don’t buy what they are trying to sell to you”

Youth Task Force

By Paula Welch

Paula Welch is a media specialist with Greenpeace in Atlanta.

In 1992, more than 800 people from the South gathered in New Orleans as part of an environmental justice conference sponsored by the Southern Organizing Committee. During the meeting, they came up with the idea of a regional youth organization that would provide leadership training and organizing for youth activists. The Youth Task Force was born.

YTF now has 30 coordinators in 10 Southern states and is working with 85 campuses and community-based youth/student groups in the South. “The strength of YTF lies in the ability of the organizers who are part of it to call on a network of young activists across the South to help in times of struggle,” said Angela Brown, YTF’s director.

One of the major focuses of YTF is Countdown 2000: the Black Youth Agenda. Young people across the nation will work collectively on issues affecting black youth. YTF will facilitate a regional gathering in the spring bring hundreds of youth together from around the South. “We want to be able to cultivate the leaders of tomorrow,” said Oily Tall, outreach coordinator of the Task Force.

Another major focus of the Youth Task Force is environmental justice and health issues. The Task Force is planning a conference with the Black Women’s Health Project, Greenpeace, and the Southern Organizing Committee in Atlanta. The Task Force and other conference planners hope to build a broad-based health and environmental justice movement dedicated to protecting future generations of African-Americans from toxic contamination and exploitation.

“The young people who live in contaminated communities will be the next generation to bear this burden if we don’t start making links now,” said Brown.

Black Student Leadership Network

By Lee Richardson

Lee Richardson is a 1995 graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Founded at Howard University in 1991, the Black Student Leadership Network emerged from a Children’s Defense Fund conference. Working with the child advocacy organization, the network developed to educate and mobilize black college students “to pick up on the legacy of the African- American struggle by keeping the youth at the forefront of activism,” says Darriel Hoy, the Southern Region Field Organizer for the network.

The network is a group of more than 600 college students, community-based activists, and other young adults working to improve the lives of children. The organization has designed programs to work with children directly, “but service alone doesn’t make change happen that will last,” says Hoy. The organization also focuses on legislation, working with parents how to advocate for children.

“Youth have the energy, time, and resources to create a new generation of servant leaders. We (youth) have some responsibility, too.”

The network is the place that Hoy has found to become a “servant leader.”

The network sponsors the Ella Baker Child Policy Training Institute, named for a leader of the civil rights movement. (She served as advisor for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Executive Secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1960s.) The Institute aims to train 1,000 young African-American leaders by the year 2000.

The Institute also conducts Freedom Schools across the country. The name hearkens back to the 1960s when Mississippi communities closed public schools rather than integrate. Volunteers staffed those schools to teach black children being denied their education. The new Freedom Schools, says Hoy, “provide children in impoverished areas with educational and recreational activities. They provide a safe space for children and provide a meal through the government’s summer food service program” (a government program in jeopardy due to budget cuts by the U.S. Congress). “In addition, college interns develop leadership tactics to mobilize local communities for grassroots activism.”

Tags

Chris Richburg

Chris Richburg and Terri Boykin attend North Carolina Central University in Durham, North Carolina, and are interns with Southern Exposure. (1995)

Terri Boykin

Chris Richburg and Terri Boykin attend North Carolina Central University in Durham, North Carolina, and are interns with Southern Exposure. (1995)