Death Penalty

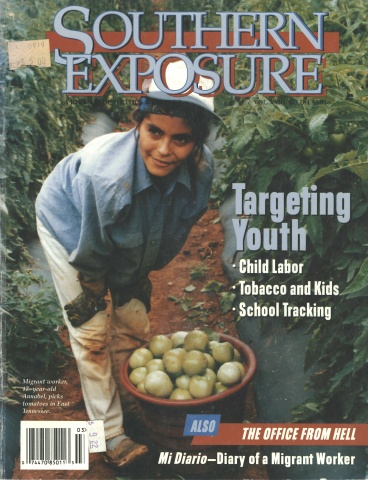

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Down South, we’ll fry up just about anything: chicken, possum, steak — and people.

“Many would argue that in the old Confederacy, a place where it was believed to be acceptable at one time to own another human being, the popularity of capital punishment is not surprising,” says Malcolm Hunter, the Appellate Defender for North Carolina.

The tradition of tough justice continues today in the South. Every Southern state except West Virginia allows the imposition of the death sentence (13 of the 38 states in the rest of the country do not execute prisoners). Of the 289 prisoners executed in the United States between 1976 and 1995, the South put to death 236. Texas topped the list with 97 executions. Florida, Virginia, Louisiana, and Georgia each put more than 20 prisoners to death. Texas also has the most prisoners on death row — 398. Florida ranks second for inmates awaiting execution with a total of 342.

As in other aspects of Southern culture, race plays a role in punishment. While blacks make up only 12 percent of the general population, they occupy nearly half of the spots on death row. But according to Beth Daniels, Administrative Coordinator with the Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, “The biggest racial disparity is related to the victim. A person is much more likely to get the death penalty if their victim is white than if their victim is black.” The majority of people who are sentenced on death row were there for killing white people. If a white person kills a black person, it’s much less likely for him to be on death row. “It’s comparatively heinous,” Daniels says. “If you’re black and kill a white person, you’re 11 times more likely to get the death sentence than any other combination of races.”

The South’s tradition of racial discrimination in handing out punishments is rooted in slavery. Under Georgia’s statutes of 1816, the crime of rape or attempted rape of a white woman by a black man was made punishable by death while whites faced only two years in prison for the same crime. In 1848, Virginia enacted a statute requiring that African Americans be executed for crimes for which whites would only be imprisoned three years.

In 1970, discrimination was still an issue. The U.S. Supreme Court heard the claims of a black Arkansas man charged with rape who pointed out that while the rape of white women by black men was consistently punished with death, rape by whites was not. The court failed to act in his favor.

The Supreme Court did encourage uniform state death penalty statutes that would increase the probability of equal justice, but many Southern states kept their laws regarding capital punishment vague, allowing judges a great deal of leverage in assigning the death sentence.

In response to continuing harsh and unequal punishment, groups have worked outside and inside prisons to protest the death penalty and promote the humane treatment of prisoners.

The National Coalition’s Beth Daniels says her organization wants to see the death penalty eliminated. “We see the death penalty as a moral and policy failure,” says Daniels. “We want to spend money, energy, and time to make the country really safe through organizing and education.” To those ends, the National Coalition encourages public debate in states that consider instituting capital punishment. In Iowa, their efforts helped stop attempts to institute the death penalty.

Just as important, the prisoners themselves have worked to show the outside world that they have a face and a voice. The Angolite, a magazine published by and about prisoners, is available by subscription to the general public. Writer Michael Glover, a prisoner at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, says the magazine is “the only uncensored prisoner publication in the nation. We offer the prisoners’ perspective on criminal justice issues. And you can’t get that any place else.”

Tags

Molly Chilson

Molly Chilson and Wendy Grossman are interns with the Institute for Southern Studies. (1995)

Molly Chilson is a freelance writer in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)

Wendy Grossman

Molly Chilson and Wendy Grossman are interns with the Institute for Southern Studies. (1995)