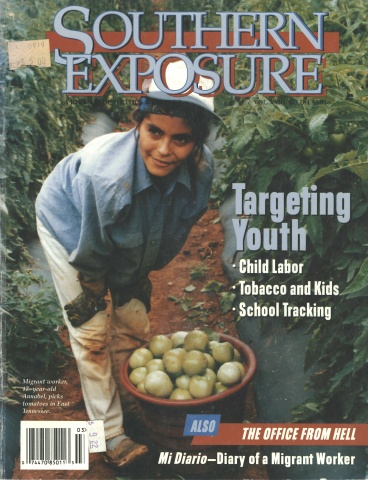

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

"It’s the fifteenth of October, you know,” the doctor said as we were walking. “That might be of some significance.”

Allegra was on my right, the doctor a step behind us, the nurse back on the porch with the pumpkin.

“You come back here,” the nurse warned from the top step.

The doctor turned and smiled at her. The air was pale and misty with rain. “It’s OK,” he said, and pounded his chest lightly with both fists.

Allegra and I were at the magnolia tree by then. The holly bushes were guard enough, we had decided. And we were on the hill anyway. The megaphone man was curled on the pavement in the center of the driveway, just a couple feet from the old woman with the Virgin Mary poster. As usual, she was on her knees, counting her rosary beads and ignoring everything. The megaphone man was turned away from her, looking toward the sky. His steel-colored hair hung in thin damp strips from his scalp.

“He’s only relaxing, girls.” The doctor came up behind us, whispering in the space between Allegra’s neck and mine. “He does this sometimes,” he said for Allegra, since she had never seen it before. “Did someone call the police?”

The old man was mouthing silent words to the clouds. Around the rim of his orange and black striped megaphone was a blue bumper sticker: Life, it read.

“I think they’ve been called,” said Allegra, who was chewing gum.

I turned; the nurse was standing stiff on the porch steps. “Did you call them?” I asked.

The nurse nodded a faint bob, which I took as yes.

“She said she called,” I told the doctor. Allegra was right up close to the holly bushes, looking down at the megaphone man and the old woman. The doctor was hovering behind the magnolia’s tree trunk.

“Are they friends?” Allegra asked him.

“Maybe not today,” said the doctor.

“Maybe he’s embarrassing her. You think so?” The doctor winked and reached around the tree trunk to pinch Allegra’s elbow. She smiled.

“They don’t come together,” I said. “And she never says anything.”

We all watched a second longer until the police arrived in a white patrol car. A black man and a white man dressed in uniforms emerged from the front seat. They left the blue lights flashing. The black man went to the megaphone man and leaned over him. “C’mon Reverend,” he said. “We’re gonna take a trip downtown.” He pulled a pen from his shirt pocket.

The other policeman climbed the short hill; the doctor came from around the tree trunk to shake his hand.

“All of y’all should go back inside,” the policeman said, taking off his cap. “We’ll take care of this.”

“We’re going,” said the doctor, stepping backward and holding his arms out in resignation. He turned his broad, friendly face up toward the magnolia leaves and breathed deeply. “C’mon girls,” he said. “Fresh air is over. Back to work.”

Down in the driveway the black officer was writing in a slender notepad, one booted foot resting lightly on the megaphone man’s waist. The old woman was still counting rosaries, and the Virgin Mary’s poster board was wilting in the soft rain.

The doctor and Allegra had a head start on me. “Hurry, Coll,” said the doctor. He paused and nodded his head toward the nurse, who had sat down next to the pumpkin. “She’s getting worried.” He raised his eyebrows.

We were close enough then that the nurse could hear us. “I’m not worried,” she said. “I don’t worry about stupid people.”

The doctor laughed softly and marched up the steps. He tapped the pumpkin with his knuckles; his stethoscope swung forward and he caught it with his wide hairy hand. In the gray light his wedding band shone dull copper-gold. “It’s a good one,” he said of the pumpkin and stood upright. “October fifteenth,” he said, and opened the front door for Allegra. “Let’s carve it.”

By the time the nurse brought in the pumpkin, the TV people were in the lobby. I was behind the front desk, wiping cracker crumbs off the counter. A man who might have been a midget was standing on a chair, hanging a light above the doorway. In front of our snack machine, an anchorman knotted his tie.

The nurse had the pumpkin balanced on her hip, one arm curved beneath it. “Y’all need to get out,” she said to the TV people. I could imagine her saying the same thing, in the same way, to a room of teenage boys. Her hair gleamed blue-silver under the midget’s light when he moved it toward her face. A man with a crackling radio on his belt bobbed a microphone to her chin. She leaned forward. “Get out now,” she announced. Her voice lilted across the lobby. Nobody was there except for the TV people and us; all the women had been taken care of by then.

The nurse looked down at the pumpkin and over to me. “This will have to wait,” she said.

In a small room, where the window was tinted [purple, Allegra and I shredded papers. She had her shredder and I had mine, both of them white bins crowned with hissing metal teeth. The megaphone man was back on the sidewalk, and when he stole our garbage he would have paper strips and remnants of everyone’s lunch.

“The police didn’t keep him long, did they?” asked Allegra.

“Two days is longer than most of the time,” I told her.

“I thought he looked rather peaceful,” Allegra continued. The sun shifted a degree and the walls of the room colored lavender. Outside, the October sun was hot as August, so hot that those who were waiting in the parking lot couldn't sit on the cars and sat on the curb instead. Music from their radios thumped in a swelling beat.

“Peaceful?” I asked. “He looked crazed, if you ask me. But that old woman, she looks peaceful. She is peaceful. The man isn’t. He’s always yelling, in case you haven’t noticed.”

We both stopped shredding papers and fell quiet as if to prove something. Sure enough, I heard his shouting. Even over the car radios. His crackling, amplified voice carried toward us. I couldn’t make out the words, but I had often enough heard what he had to say.

Allegra unplugged her shredder and leaned back in her chair. From a thin chain a gold crucifix shimmered in the hollow of her neck. Gold metal against her warm yellow-brown skin.

“Can you keep a secret?” she asked.

I shrugged and took up my stack of papers to count them. They weren’t much, really, nothing that the megaphone man would get excited over. Just appointment slips and a few messed-up forms. But all of them had names. And names had to be protected.

“I'll tell you a secret,” she said, and lifted her black hair into a horse’s tail. “It’s about the doctor.”

“What is it?” I asked. The doctor was well protected. He wore a vest outdoors; the windows were bullet-proof and had been tinted so no one could see him or us.

“He is in an unhappy marriage.”

I shrugged again. “That’s not a secret.”

Allegra tilted her head and looked through the window. Outside, two small boys were bouncing a basketball back and forth on the pavement. “Good, then. I’m glad it’s not a secret. I usually wind up telling things I shouldn’t. When I was little, my brothers called me the Walking Newspaper, because I was always going around telling everybody about everything. Even when I didn’t know the whole story, I would make something up, just to get attention.”

I smiled. “OK, Newspaper,” I said. “I’ll remember that.”

Allegra laughed a little. “You know what?” she said. “You’re OK. I thought you weren’t, but you are.”

I dropped the last of the paper into the shredder. “I am OK,” I said, watching with satisfaction as the names were eaten.

The woman in the waiting room had a worry stone, a round flat pebble about the size and shape of a candy mint.

“You should go in with her,” I whispered to Allegra, who was dropping pills into souffle cups. “You haven’t gone in yet, have you?”

Allegra shook her head and counted souffle cups.

“Then you could go with her,” I said. “She’s worried, see?”

I looked over to the woman who was rubbing the worry stone. She had that look. I could not describe it. Something on the verge of something in her eyes. Not fear, not indecision. Just worry.

Allegra slid the tray of souffle cups over to me. She lifted a stack of magazines from the counter and moved toward the row of chairs where all the women were waiting. She paused when she approached the woman with the worry stone. “Hey,” Allegra said. The woman looked up. “You want someone to go in with you? When you see the doctor, I mean?”

The woman paused and nodded.

Allegra hesitated, then nodded over to me. “She’ll go with you,” she said. “Coll has been in lots of times.”

The woman looked suspicious. “Have you?” she asked me. Other women were watching us now, the whole room of them. Everybody except for me and Allegra was dressed in surgical gowns and booties.

“I can go,” I offered. “I can hold your hand if you want.”

Another woman snorted. “You don’t need to hold my hand,” she said. “I’ve done this before.” Some of the other women laughed and nodded.

“OK,” said the woman with the worry stone, “that would be good.”

Allegra turned on the TV. A game show was running. We all played along, giving answers to the trivia questions. Then the game show was replaced with a soap opera. In the opening scene, a woman in the back seat of a car was having a baby. She grunted and sweated and moaned until the baby was born. Everyone in the waiting room was silent for a moment until someone clapped her hands, and then someone else, and then someone else, until all of us were applauding.

“Look what was on my car,” said Allegra. “Under the wiper blades.”

“Pictures,” I said. “A gift from the megaphone man.”

Allegra handed me the brochure; I folded it out on my desk like a map. It was pictures of bodies. White knobby bodies floating in watery bubbles. Bodies with little bead eyes. Bodies magnified. As small as a paper clip, I always said to the women. That was one of those things I said over and over again, along with other things: Three to five minutes, cash only, have someone drive you home.

I plugged my shredder into the wall socket. The pictures dropped into the bin: long narrow dark strips. It was morning and the light above us was warm and yellow. The purple windows were dark, but it was a dark morning and even the megaphone man was just getting started. It was easier to make decisions in the morning, I had read. It was a good thing, then, that we always opened early.

Allegra balanced herself on the edge of the shredder bin and watched the pictures fall. “I had a nightmare last night,” she said.

I unplugged the shredder. “That’s normal,” I replied. “Everybody has that happen.”

Allegra reached into the bin for a strip and wound it around her pencil. “But I’ve never even been in,” she said. “I’ve never seen it done.”

“Then you should go in.”

“It won’t stop the nightmares, though, will it?”

“Probably not.”

“Do you still have them?”

“Sometimes.”

“Tell me what happens.” She leaned backward and closed the door with her foot.

The TV people kept coming back. One of them, a woman in a burgundy suit and big black glasses, wanted to interview me. We sat in the room with the shredders and the purple window. The TV woman had a microphone with a puffball at the end. She placed it in the center of the table and then aimed her pen at her notepad.

“Just tell me,” she said, “just tell me what you think everyone should know.”

My nightmares are about bodies. Purple bodies, red bodies. I dream I am the doctor, and the bodies come out alive and talking. Other times I am swollen and deflated, and things fall from me: a set of fingers, an ear, or nothing at all, when I’ve been expecting something.

I dream I’m under them, above them, that someone is taking them all away. I want to rescue them. They are being taken from me, stolen away, wheeled away on a big cart, stacked one upon the other.

In other nightmares the bodies are grown-up: a heavy, smothering load. They fall on me.

I can’t support all of them.

“You and Allegra can do it today,” said the nurse. The pumpkin was still not carved and Halloween was coming.

In the lounge we spread newspapers on the coffee table. “Look here,” said Allegra, pointing.

On the newspaper page was a picture of the megaphone man, curled up in our driveway. I paused and scanned the page carefully.

“They forgot the old woman,” I said. “She would have made a better picture.”

Allegra found a knife and towel. She washed the pumpkin clean. I had the pencil. “I’ll make a cheerful face,” I said sitting on the sofa. “Nothing scary.”

“A jack-o'-lantern is always scary,” said Allegra.

“You’re right, I guess,” I said, and ran my hand over the pumpkin’s blank face. “Do you think we should do this?”

Allegra shrugged; her lashes darkened the skin beneath her eyes. She exhaled a soft laugh. “Are we going to dress up, too?” she asked sarcastically. “The four of us. We’ll be a witch, a skeleton, the grim reaper, and the devil. How’s that?”

I put down the pencil. “You’re right. We shouldn’t.”

Allegra sat beside me. She was thinking. “But we don’t have to put it on the porch where they can see it. We can keep it back here.”

The nurse came into the lounge; her spongy shoes scuffed the flat carpet. “How’s it going, girls?”

“We’re wondering if we should do this,” I said. “Do you think it will scare them when they walk in? I mean, they’re nervous enough already.”

The nurse poured coffee. She had her own mug, which said Paradise Travel on the side. Her son was a travel agent. She leaned against the counter and took a sip. Her eyes were tight blue behind her frameless glasses. “You girls are silly,” she said. Her face flushed pink like her turtleneck shirt. “Really ridiculous,” she continued. “It’s Halloween and we are putting a jack-o'-lantern on the front porch. It’s nothing to be afraid of.” She stood still for a moment, her eyebrows tensed, and then she left the room, balancing her coffee cup in her palm.

Allegra followed the nurse into the hallway. “OK,” I heard her say. “Show me what’s not scary.”

The woman said that I was to hold her hand tight and not let go no matter what. The worry stone was a smooth orb nestled between our palms.

The doctor opened the door and walked in. A pair of clear plastic goggles hung from a strap around his neck.

“I’m just holding her hand,” I told him.

“No problem,” he said. All of us smiled.

The doctor sat on a small wheeled stool and viewed the woman’s chart. “You’ve had one child?” he asked.

The woman nodded. Her eyes were shiny with trust.

“This will be nothing then.” He slid around, flicking on a bright spotlight before he pulled the instrument tray toward him.

The woman closed her eyes. “Relax,” I said, and remembered a word that Allegra knew: Tranquilla. A much prettier word. I recited it inside myself. The worry stone numbed my palm, and the woman breathed in fast and flinched when the doctor began.

“Hold on,” I said. Tranquilla. I looked over to the doctor. “It will pass quickly,” I told her.

The woman’s fingernails sank deep into the top edge of my hand, right below the knuckle of my pinkie finger. “Relax,” I said again. I was not watching the doctor anymore, but was looking toward the ceiling’s edge, where there was a long square window that offered a simple view, a square of sky and a bit of electric line. But light passed through into the white room, clear light with no tinting.

“All finished,” the doctor said finally. He covered his instruments with a paper towel. “Help her up, will you?” he asked me, and lowered the goggles back around his neck.

The woman opened her eyes. “Thank you,” she said to the doctor. But he had already left, and the door was falling closed.

The TV woman’s glasses flickered in orchid light. “What else do you need to say?” she asked me.

I had been talking little. My words were hasty words, like the fluttering music of a cat crossing a piano’s keyboard.

I remained silent and considered Allegra, the Walking Newspaper. I was the opposite, the one who knew everything, but said nothing.

“Go on,” said the TV woman, leaning forward, urging me with her eyes. Her pen was aimed tight and tense toward her notepad, the recorder was spinning obediently. When she got back to her office she would curse me as she listened to long intervals of tape-recorded nothingness.

“Tell me,” she said again, “what people should know.”

It was when I counted the money that I thought about the old woman who was on the other side of the window. I even watched her sometimes, just for a few minutes, before I started counting. I could watch her alone then, because when the counting time came, no one could come in the little room except for me. I locked the door. Allegra had to talk to me through the keyhole if she wanted something, and she asked me once: “What are you doing in there every day?” and I said “Counting.” And she said “Counting?” and I said, “You know, doing the books.” And then she understood, and was curious but quiet.

And so when I counted all that money, and there was a lot of it, I thought sometimes about the old woman who was outside counting prayers on her little plastic beads. If I turned toward the purple window I sometimes saw her there, her face gray and tight, fingers kneading. She was asking for something. And me? I was with the money, piling gray-green bills into stack after rubber-banded stack. Enough that I never got over the shock, never stopped thinking about how I could live for a year if I stole a day’s worth. And that was why I thought about the old woman’s prayers then: she thought they were something I needed.

The nurse was just taking the jack-o’-lantern to the porch when Allegra came back into the lounge. My hands were coated with pumpkin; the newspaper heavy with seeds and stringy yolk. I folded the printed pages and carried it like a baby’s diaper to the trash. The smell was light and warm.

“I need to talk to him,” Allegra said. Her face was pink, her eyes sparkling dark.

“To who?”

“To him,” she said. “I was just in there.” She leaned against the trash can. It flopped against the wall from her weight.

“Well then, you should have talked to him then. I’m sure he’s gotten busy again now.”

“Not in there,” she said. “I was in the scrub room.” She raised one hand up to her collar bone, massaging the ridge. She spoke quickly, spitting her words: “I saw everything there. Everything he does. Some doctor.”

Our only dish towel was already wet on one side from a coffee spill. I cleaned my hands on the dry edges. “Why don’t you go home and sleep, Allegra?” I said. “It’s been a rough day.”

Her bottom lip trembled. It was cracked and shiny. “You don’t understand,” she said. “It’s not the same for you.”

The doctor’s whistling came from outside the door. “Coffee break,” he said jovially as he entered. His gaze lingered on Allegra, his eyes asking a secret question.

I turned to the sink and ran a water stream to clean my hands. I would use soap even, to take a long time and not watch them. But when I heard Allegra open her locker door, I turned back in time to witness their lovers’ huddle. The doctor’s eyes probed hers. She focused her gaze downward, onto his stethoscope. “I’m leaving,” she said softly. She withdrew her purse from her locker, ducked under the doctor’s arm, and retreated down the back hallway.

My hand was bleeding: Four crescents shaped like smiling mouths. The nurse brushed them with cotton and alcohol.

“Look what she did to me,” I said. “She pushed her fingernails right in, like I was a pillow or something.” My anger stung much worse than the four little wounds. I did not deserve this injury. I had been helping and should not have been harmed. But the women, all of them so needful. Needing something was their crime, and they deserved their pain.

“Oh, it could be worse,” said the nurse, who had been around long enough to have seen the worst of everything, to know all the stories. Everything that had happened and was told again always began with the time.

The time a TV reporter jumped over the front desk to get an interview with the doctor. The time a woman got in the stirrups and pulled a knife from her sock cuff. The time the megaphone man chained his neck to the front gate.

And then there were other stories, perpetual stories, preceded with all the times: all the times they called and played lullaby music into the phone. All the times they sealed the locks with glue. All the other times they robbed the dumpster.

“There you are,” said the nurse, taping a bandage on my wounds. She was crisp and calm in her uniform, in her starched chlorine-white pants and jacket, the creases in the legs and arms so sharp. A tiny bird-shaped brooch — a nightingale — sparkled like crystal on her breast pocket. The nurse had told me once that the male nightingale sang its prettiest songs at nighttime, to lure the female into mating.

Imagine a dark, peaceful place. It is the warmest, safest, most comforting place you have ever been. Then you hear something, a soft hum, calling you away. All at once, without pain, you are there, going toward the call. Soon you find yourself in another dark peaceful place.

What could be wrong with that?

Three women agreed that nothing was wrong. They signed papers to prove their convictions.

“Now follow me,” I said. I took them to the waiting room and passed out gowns, thin clean gowns so soft you could pierce the fabric with your thumbnail. I was offering comfort. After that, I would find blankets, magazines, cups of soda. I would give them what I could.

And Allegra had come back after all. She entered with a tray of medicine; each souffle cup contained two little pills. I smiled as I took the tray.

“This is it,” she whispered. She raised a finger to her crucifix necklace and stroked the gold bars. “After today,” she said. “I am leaving.”

My anger was sealed and wrapped as tight as my four little wounds. I went to the recovery room to see the woman with the worry stone.

“Thank you,” she said when I sat down beside her. She was dressed in street clothes and drinking juice from a paper cup. The nurse was busy in the back closet, writing on a clipboard. The late afternoon sun fell lazily through the windows. Soon it would be time to go home, to leave. But first there was cleaning, paperwork, money to count, and the trip to the bank next door to drop off the deposit.

“You are very brave to work here,” the woman continued.

“Thank you,” I said.

She set her juice cup on the small table, which was littered with torn-up magazines. She dug her hands into her jeans pocket and then opened her palm before me. The worry stone was nestled there, shiny and smooth. “I’ll give you this,” she said. “I won’t be coming back here again.”

I could have said: You will have other worries. You should keep it. Yet I lifted the stone from her palm. It was a little load I would carry, because she thought it was something I needed.

Allegra left as Halloween night emerged cold and blue. She and the doctor and the nurse stood side by side before the front desk, where the doctor gave her a paper to sign. The paper said she was leaving of her own free will, and was obliged to keep everyone’s name a secret. She scratched her signature on the page and snatched her paycheck from the nurse’s hand. I was standing by the doorway, huddled in my jacket. A patrol car was in the drive, blue lights flashing gray through the purple window.

The three of them crossed into the lobby. The doctor held Allegra by the elbow. She pulled away when she saw the lights. “Why are they here?” she asked, her breath a gasp.

“Just a procedural thing,” said the doctor. He was wearing his vest.

I opened the door. Cool air rushed. On the porch, the carved pumpkin shell sat, unlit, its jack-o’-lantern face pointed away from me.

Allegra came forward, still freed from the doctor’s grip. “Coll,” she said, and slowly extended a fist toward me. “Open your hand.” I did so, and she dropped something onto my palm. It was her crucifix necklace. “Think about it,” she said, and then the doctor took her elbow again, gently pushing her forward.

Allegra spun around, her hair snapping her chin. “Don’t touch me again,” she said. “You murderer.” The doctor’s face softened and he shook his head. Allegra wrapped her arms around her chest and stepped onto the porch. She paused one second before she raised her right foot toward the pumpkin, kicking it hard. The shell raised about the step and cracked into thick splinters, which fell soundly down the cement stairs.

We all watched as she ran lightly down the sidewalk toward her car. The police lights churned; her body flickered in the colored light.

The TV woman closed her notebook, flicked off the tape recorder and rubbed beneath her glasses. “You’ve been very helpful,” she said.

“Thank you,” I answered. I considered how much of the tape was filled with my words, with my halting, meager sentences. Not much of it.

“It’s often struck me as strange,” the reporter continued, opening her purse to stash the notebook inside, “that people who work in the most interesting places often have the least to tell.”

I nodded. “It is that way, isn’t it?”

She paused. “Are you sure?” She was ready to hear more.

“Oh yes,” I said. “The other side is much more exciting. In here, there’s not a whole lot going on. We just have our jobs, you know. It’s a job like any other.”

“Thank you again,” she said, resigning herself. She wound the tape recorder’s cord into a loop. “And play it safe. It’s dangerous for you,” she said. “The other side isn’t so boring. You need to protect yourself no matter what.” She stood to leave.

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I’m always thinking about that first.”

She paused again at the door. “About what, you say?”

“About protection.”

The counting time was later in the day after Allegra left. Less people to do the work meant more of it for me. On the day before Thanksgiving, the old woman packed up early, and by the time I locked the door of the little room, she was gone.

The worry stone made a circular dent in the pocket of my white pants as I sat down to do the counting. The parking lot was empty, silent. The megaphone man had disappeared earlier, but for all the quietness outside, it had been a busy day.

I counted the money and stashed it in two canvas bags. Blue bags with silver locks. I placed one bag beneath each of my armpits and pulled on my jacket. I slid the keys to the canvas bags into my pants’ pocket, and moved the worry stone to my jacket pocket. The crucifix necklace was there. I had never worn it. In fact, I didn’t want it at all, and thought that I soon would find Allegra’s address and mail it back to her.

In the hallway, I heard the TV playing. The nurse was in the waiting room, cleaning. “I’ll be right back,” I called. “I’m coming right back.”

“I’ll wait,” the nurse replied.

Outdoors, the sidewalk was strewn with browning leaves. The cold had sapped their crunch and my footsteps were silent. The bank was right next door. Down the sidewalk, across the hill and then I would be there.

From behind the magnolia tree a figure moved forward onto the faded grass. It was Allegra.

“Coll,” she said, and moved forward a step. “Have you been thinking?”

The sun emerged briefly; Allegra’s cheeks were bright with windburn. Her hair had grown longer and fell full across the shoulders of her crocheted jacket. I didn’t question her presence. It was as if I had been expecting to see her. I stopped in my tracks.

“Thinking?” I asked. “Yes, I have.” I reached into my jacket pocket and pulled out her necklace. “I have your necklace,” I said. “Do you want it back?”

She lowered her gaze. “I’ll take it back, Coll, if that’s what you want.” She looked back at me, her eyes alive, and I moved toward her. She opened her hand; I dropped the necklace inside. The gold sparkled once before she closed her fingers around it. That golden spark — that little light — was what I remembered most clearly before the grip came around my ankle and forced me to the ground.

The megaphone man pulled me hard around to the other side of the magnolia tree. Leaves and rocks scraped the uncovered skin of my neck. He clamped his hand over my mouth. I tasted leather and car grease when I tried to scream. He moved on top of me, his knees pressing into my shins. The silver locks were cold and hard in my armpits.

Allegra moved behind him. “Don’t hurt her,” she whispered, her hands hovering over his shoulders. “Just take the money.” Her eyes shot back and forth between him and me.

“Listen to your heart beat,” the megaphone man whispered. “It’s loud enough that I can hear it.” His face was lined and brown like a walnut shell. “Scream in silence,” he said, and reached into the pocket of his coat. He pulled out a large jagged rock. Above me, the rock was a black outline, like a dark hole missing from the tender blue sky.

Allegra’s voice came from the other side of the sky, shrill and scared: Don’t look!

Then the hole in the sky fell over me, and everything opened into blackness.

Imagine a dark peaceful place. A place where anger and questions and doubts are stirring. It is in this place where you discover your choice: you have the power to draw open the curtain between blackness and colors you remember. And you know you can do it, because on the side you remember there is something that holds you, a little load you carry. A little load you needed, and can feel smooth in your fingers. And it’s this little orb that pulls you forth, that leads all other loads — heavier loads — into nothingness, and brings a little bird to your heart. And when the loads are lifted, you recognize them as you recognize the colors stirring in your eyes, and you see that they are — like everything — a means of protection.

Tags

Anne Marie Yerks

Anne Marie Yerks is editor of the feminist journal, So to Speak, and a teaching assistant at George Mason University. (1995)