This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 3 & 4, "Targeting Youth." Find more from that issue here.

It’s called the best place to live in the United States by Money Magazine. The Triangle Area of Raleigh- Durham-Chapel Hill, North Carolina, encompasses the state capital, a quaint college town, modern executive business parks, beautiful homes, expensive cars, and lush landscape. Just a few miles away, in the small town of Pittsboro, Caroline Penny, a 41-year-old mother of two who takes care of her elderly parents, lives without plumbing.

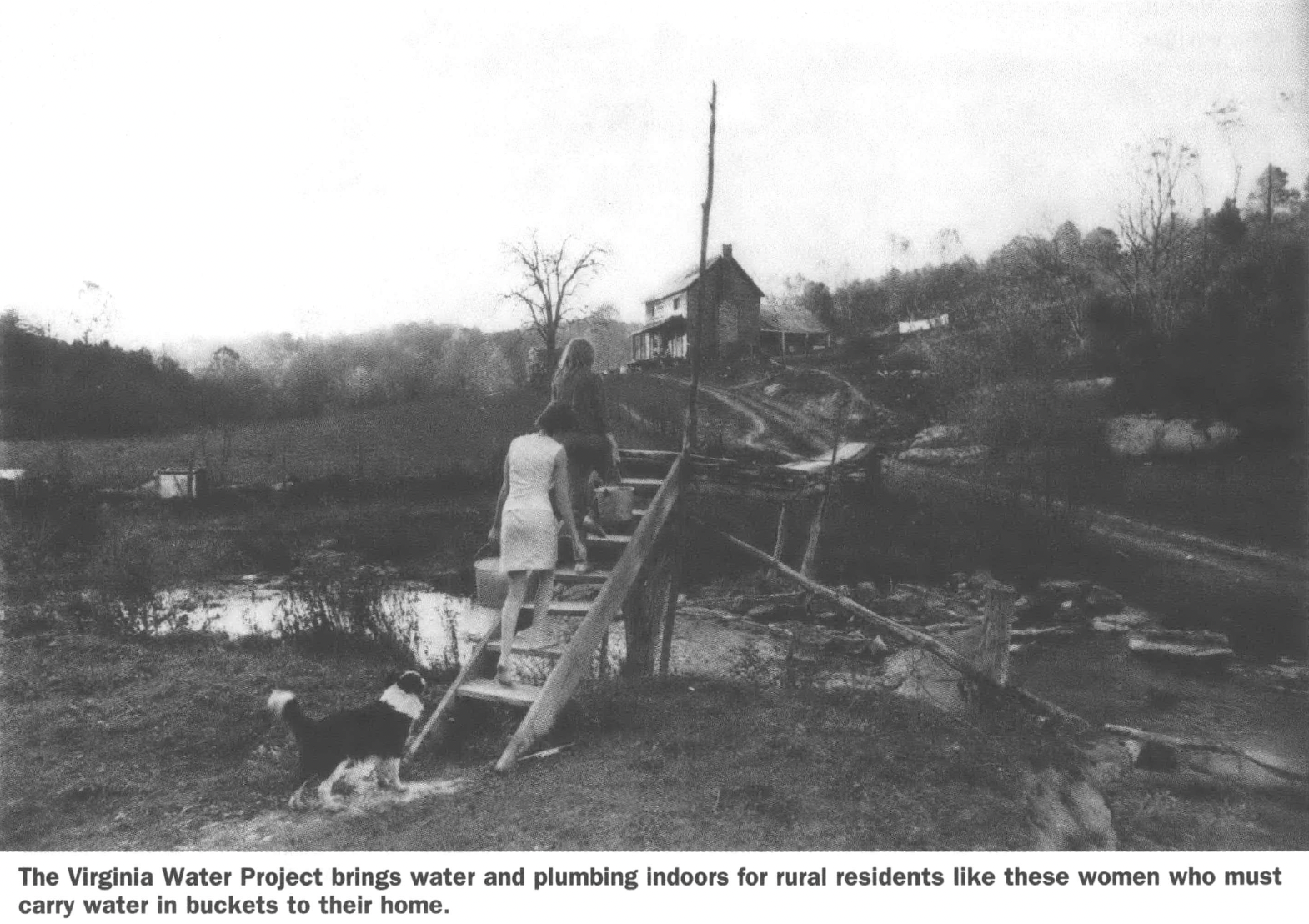

Penny used to carry water in buckets a quarter of a mile from a local church. Recently, when the church locked its well, a four-mile journey by car into town became the only alternative. “It gets hard sometimes,” Penny says, “but it’s the only way we have to get water.”

On Delaware’s Rehoboth Beach, affluent people play in the sunshine. Right next door to the wealthy resort is West Rehoboth where a poor, mostly black community lives without basic plumbing or safe drinking water. Every day, 280 families are threatened with contaminated wells and exposure to raw sewage.’’ Lots of people just ‘straight-pipe’ their sewage in back of their homes or into nearby creeks,” says Bill Coleman, a water specialist in Delaware.

The problems of Caroline Penny and the community of West Rehoboth Beach are not especially unusual in the South. According to the 1990 U.S. Census, 1.1 million people in rural America live without adequate indoor plumbing or running water. Of the 10 states with the most homes lacking indoor water or plumbing, nine are in the South.

Kentucky leads all states with 30,921 homes lacking indoor water or plumbing. Virginia follows with 30,003. In North Carolina there are 27,743 households, 26,028 in Texas, 19,438 in Tennessee, 15,812 in Alabama, 15,443 in Georgia, 14,926 in West Virginia, and 14,849 in Mississippi. The total number of people in these households is 502,518 — half of all people in the U.S. without adequate plumbing. (Ohio is the other state in the top 10.)

“The problem of lack of water is large and often hidden,” says Peter Kittany. He directs the North Carolina Rural Community Assistance Program, a community action agency in Pittsboro that works with water issues. The poor and people of color are most likely to be part of the hidden population.

The issue is not invisible to everyone. The Virginia Water Project/Southeast Rural Community Assistance Program is bringing water, plumbing, and other assistance to West Rehoboth Beach, Caroline Penny, and others in the Southeast. Based in Roanoke, Virginia, the program evolved out of Total Action Against Poverty, an anti-poverty agency that began in the mid-1960s. The organization went into rural communities around Roanoke to survey residents about their most critical needs. The surveyors found that the most pressing issue was the lack of safe drinking water.

The group decided to create organizations to help low-income families in the area gain access to safe drinking water. The local project has mushroomed in the past 30 years into a safe drinking water and waste water service agency with programs nationwide. The programs serve more than 300,000 rural residents in Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Those involved with the program recognize that inadequate indoor plumbing is often compounded by other adverse conditions in impoverished communities. Thus, they tackle economic instability, land loss, poor health conditions, and inadequate education.

“Water and waste water issues unlock the door to a number of community economic justice issues.” says Cynthia Martin, director of the Southeast Rural Community Assistance Program. “When we address waste water issues, we also try to address housing, unemployment, and weatherization.”

With funding from both public and private sources, the Virginia Water Project/Southeast Rural Community Assistance Program works through local nonprofit community action agencies in the Southeast. These agencies provide a link between the communities, other agencies, and their states.

“We might get a call for our help from a community that’s heard about our work or a local government agency to tell us to help a community having trouble complying with water regs,” says Peter Kittany of the North Carolina Community Assistance Program. His group assesses needs of the community and provides on-site technical assistance, training, and advocacy in water, waste management, and related issues, such as housing and weatherization.

Local residents are involved in the process from the beginning, says Bernice Edwards, director of housing and rural development at the First Day Community Action Agency, the lead agency for the project in Delaware. “We ask people what their needs are instead of telling them,” Edwards says. “What’s happened in a lot of instances [in the past] is that things have come from the top down.”

Improvements in rural communities come through several programs provided by the Virginia Water Project/Southeast Rural Community Assistance Program:

♦ Technitrain — The Technical Assistance and Training Grant Program provides development and support. The Southeast Rural Community Assistance Program works with its lead agencies in the seven-state area to construct or improve water systems. They help rural communities complete needs assessments, work with engineers, and examine funding options. The program also helps those communities that do have waste water facilities maintain them and stay in compliance with state and federal regulations.

♦ ACTTT (Achieving Compliance Through Technology Transfer) — This program helps rural communities comply with federal drinking water standards. They provide on-site technical assistance, workshops on water and waste water management, and information about funding alternatives. The technical training includes guidance about sampling and reporting water tests to the federal Environmental Protection Agency, leak detection in existing water lines, and how to search for new water sources when the present source is polluted.

One of the most innovative parts of this program is community-to-community peer exchange which enables community leaders to meet and share knowledge with other leaders who have solved water and waste water problems.

♦ Technical Assistance-Seeking Solutions — Under this program, the Virginia Water Project gives grants to low-income families and individuals to pay for water connection and hook-up fees. These grants can also help pay for the cost of constructing community wells for low-income, isolated communities which have no other water source.

♦ Rural Water and Waste Water Loan Fund — This program aims to increase access to federal and state funds for small and low-income communities for water and waste water facilities by providing affordable, low-interest loans from the federal government. The program also has a million dollar loan from the Ford Foundation to provide sewer line extensions, storage tank repair, and construction of community wells. Local governments, public service authorities, and nonprofit organizations engaged in rural housing or economic development are eligible.

♦ Groundwater Protection Program — This service, which began in 1985, provides technical service and education to rural communities on groundwater protection, well testing, groundwater pollution potential mapping, and groundwater protection management.

Nationally, the Rural Community Assistance Program spends more than 5 million dollars a year providing on-site technical assistance to more than 800 communities in 48 states. Their work impacts more than a million rural residents.

Their work certainly has helped West Rehoboth, Delaware. Thanks to the Virginia Water Project, residents have gotten a grant through the First Day Community Action Agency to provide running water. The group provided funds for housing rehabilitation and weatherization.

Pittsboro resident Caroline Penny, who had to haul her water four miles, has also benefited. With the aid of VISTA volunteers from the federal government, the North Carolina Rural Communities Assistance Project has helped more than 28,000 people in more than 100 communities in North Carolina replace their outhouses and failed septic tanks. The organization is helping people in Chatham County — like Penny — apply for a Department of Housing and Urban Development grant for water services.

Life is improving in other Southern communities as well. The Maryland Rural Development Corporation has helped provide water and sewer services and housing rehabilitation to the Bellevue community, a black community affected by coastal development.

Duvall is a black community less than 100 miles from Washington, D.C. in one of Virginia’s poorest counties. The Virginia Water Project, through its environmental justice project, is helping the community to find affordable alternatives to critical water and waste water issues. Over 30 homes in the community are currently without safe drinking water, waste-water treatment, and indoor plumbing.

Twenty years ago, households in need of water and waste water facilities were far more widespread. In Virginia alone, more than a quarter of a million households had no indoor plumbing. Now, the total is down to only 20 percent of that number, thanks in large part to Virginia Water Project/Southeast Rural Community Assistance Program.

Tags

Monica C. Jones

Monica C. Jones is a staff writer with the Southern Organizing Committee in Atlanta, Georgia. (1995)