This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

He seduced me with water. I was six years old, landlocked, moved inland from the Georgia seacoast to Atlanta. Around me there were only houses and woods. I searched our backyard for water, the trace of rain down a red clay hill. Perhaps this is the beginning of a stream. I dug at our hillsides with my fingernails, sticks, broken rocks. I created reservoirs. I collected water in tin cans. It was never enough.

And so I was thirsty, open to seduction. The day before Christmas 1958. It was a shirt-sleeve day and I was wearing my red corduroy bedroom slippers. My mother said I could wear them outside if I stayed on the flagstone walk. But I wandered. Down the hill to the street to check the gutters for water and down the street to the voices I heard four houses down in a neighbor’s yard. These were the big boys, forbidden.

I was lonely. We’d lived here only three months and the neighborhood children, there were so many of us then, had not yet let me into their circle. They would each play with me alone, but when the gang gathered they merged and became an angry animal. I was the littlest, the quietest, and one first spotted by predators. I had no friends and I had no father.

There was a father, true, but he worked. He left the house before I got up in the morning and came home at dinner time and at the supper table he talked about work. After dinner he went into his office and didn’t come out. Each night before I went to bed, I stood next to his desk and offered him my cheek and he kissed me goodnight. He did not take me in his lap and ask me how my day had been. He did not bend his ear to the whisperings of his child. He didn’t know what I wanted for Christmas. He didn’t know where I got the scab on my knee or that I thirsted for water.

I saw the big boys and thought they would not play with me so I turned to walk back up the hill.

“Wait, wait,” one of the boys, Roger, called out to me. He was thirteen, tall with some acne and black-rimmed glasses. My parents said to stay away from him. He went to a special school. He lived alone with his father because his mother had left.

Roger stepped away from the others. “We were just talking about the pond. I wanted to go there but they won’t go with me. Will you?”

I stopped, three feet tall in red corduroy slippers.

“There’s a pond?”

“Yeah, at the end of the road. There’s a creek and a pond. C’mon, I’ll show you.”

I followed him, forgetting the limits of the flagstone path. We passed six houses on either side of the street. The mothers were inside, talking on their telephones, pulling laundry from their new dryers. They no longer hung their clothes outside to dry. Any one of the mothers, had they been standing at the clothesline, would have stopped us. They would have sent me home.

Our street dead-ended at the black-and-white striped barricade studded with red reflector lights, the same as those on our bicycles Here we roller skated in the cul-de-sac. The big boys rode their go-carts down the hill, jerking the steering bar as they skimmed past the barricade. Until now it had been the end of the street. I was six years old; it might as well have been the end of the world.

I followed Roger past the barricade and into the woods. There was a footpath laid with fall leaves turned brown. The path led to the pond and around it. I followed Roger quietly — he didn’t talk to me — to the other side. For a child who longed for water this pond was a gift, a Christmas miracle of the sort the nuns proclaimed at school. I smiled at Roger but he didn’t smile back.

He picked up a smooth flat stone and tossed it with a quick snap of his wrist, hand palm up. We watched together as the stone skipped once, twice, again, then sank into the pond.

“Is the water deep?”

“Over your head. It’s over mine. It’s so deep you can’t measure it.”

Roger never looked at me when he spoke, he stared straight ahead, and I stared at him wondering if his red raw acne hurt.

“There’s whole cars down there and there’s skeletons in them. If you try to cross, they reach up with their bony hands and they pull you under. They suck the air out of your lungs and you drown.”

I wasn’t afraid of water but I was afraid of skeletons. When I was three, I dreamt a skeleton was chasing me down a long dark corridor. The only way out was through a keyhole. I’ve carried the memory of that dream for 38 years — when I was six, it was vivid and dangerous. I moved closer to Roger, hoping he would take my hand. As I brushed up against him, he stiffened.

The pond no longer drew me. It was something ugly, unlike the ocean at Tybee Beach, buoyant with salt water, warm as a bath. I began to feel homesick. My mother would be missing me by now. I should have been on the flagstone walk.

“I’d better go. My mom’s going to be mad.”

Roger looked at me.

“You can’t go home. You can’t ever go home again.”

Something started pressing on my chest, it pressed from the inside.

“I can too. I can go back through the woods.”

“The way we came? It doesn’t take you back. There’s only two ways to get back home. You can swim across the pond, or you can stay with me and I might show you the way back.”

“My mother will come get me. I’m going to stay here.”

He turned his back to me. “Suit yourself, but your mother’s not coming down here. You’re a good little girl. Why would she think you’d come down here when you’re not even supposed to leave your yard?”

Roger started to walk away; he was following the path up a rise. In a minute or two he would top the hill and start downward and he would be out of sight. I followed him.

My soft bedroom slippers padded in the leaves behind him. I followed him head down. The leaves beneath my feet were matted and wet and mangled by insects. I watched my red slippers take one stop and then another. I watched the red turn dark with water and mud. They were my Christmas present, wheedled early from my mother. If I never got home, they would be my only Christmas present and the woods were ruining them.

Head down, I didn’t see the rise of the hill, I merely felt it in my legs, the straining of my calves and thighs, the stretching of my hamstrings. We walked like this for some time, I couldn’t say how long. When you are six, time lurches, speeds up, slows down. My legs ached. I walked head down, my eyes on my red shoes, until Roger stopped in front of me.

The hillside disappeared in front of us. We stood on a rock ledge overlooking a chasm cut out by the stream. My curiosity overtook my fear. I walked to the rim of the ledge and looked down. The drop to the rock bed below would be, I imagined, like falling from the roof of our house.

“I’m going to push you off. You’re going to fall and you’re going to die,” Roger said.

Roger took one step forward. I had no fear of death — I had no idea what it was. Death was a turquoise parakeet named Sal buried in the zinnia bed at our house in Savannah. Death was on television.

I looked up at Roger. “I wish Rin Tin Tin were here. He’d save me.”

Roger’s face relaxed. He turned and walked away from the ledge back to the path in the woods. I followed him.

I walked on Roger’s shadow and wondered where I would sleep tonight and if I would wake in the morning. I missed my mother, but I would not cry.

The path flattened out and ran alongside the stream, which had dwindled to a trickle. I had to go to the bathroom and I was tired.

“I want to go home.”

“I told you, you’re not going home, not ever. You’ll never see your mother again.”

“I will too. She’ll find me. She’ll look for me until she finds me.”

“No she won’t. She’s mad at you by now. You’re not supposed to be here. You’re not supposed to be with me, and now she doesn’t care if you ever come home.”

I believed him. I was alone in the woods with an ugly boy who would keep me from my mother until I died. I would hardly bear the weight of my arms and legs. Roger walked and I followed him.

The sun had set and the tree limbs against the sky looked like pleading arms. I was hungry and thirsty and I had to pee. I walked in the trickle of the stream now, soaking my feet and the corduroy slippers through. If I had to stay with Roger, I would do everything I could to die.

I peed in my pants and felt the warm run down my legs and into my socks and shoes. Roger stopped and I looked up.

Ahead through the trees I saw a black and white barricade.

“That’s our street, Roger.”

“No, it’s not. It’s another street. We’re a long way from home.”

“It’s our street. I’m going home.”

The barricade was ahead, down the hill and across a small sinkhole covered with leaves. I started walking and Roger called out after me.

“There are dragons in that hole. You can’t cross it unless you know the password or they’ll eat you.”

I didn’t care. I ran, I scrambled across the hole. I ran to the barricade and around it and I was in the cul-de-sac. My thirteen-year-old sister was walking down the hill, sent by mother to look for me. My mother had been wrapping gifts, my sister watching soap operas, and they hadn’t noticed I was gone until over two hours had past.

My mother peeled off my clothes and put me in the bathtub. She kept asking, “Did he touch you?” He hadn’t.

“Did he hurt you?” I didn’t think so and I shook my head.

My mother left me soaking in the tub while she, and then my father, talked to Roger’s father on the telephone. My stomach was an island surrounded by the hot, clear water as I lay on my back in the tub. I made waves with my body and swamped the island. I watched the skin on my fingers pucker I kept running the hot water.

After a while my father came and stood at the door. “Did he hurt you?”

“No,” I said and my father walked away. I thought at least he would kiss me on the top of my head.

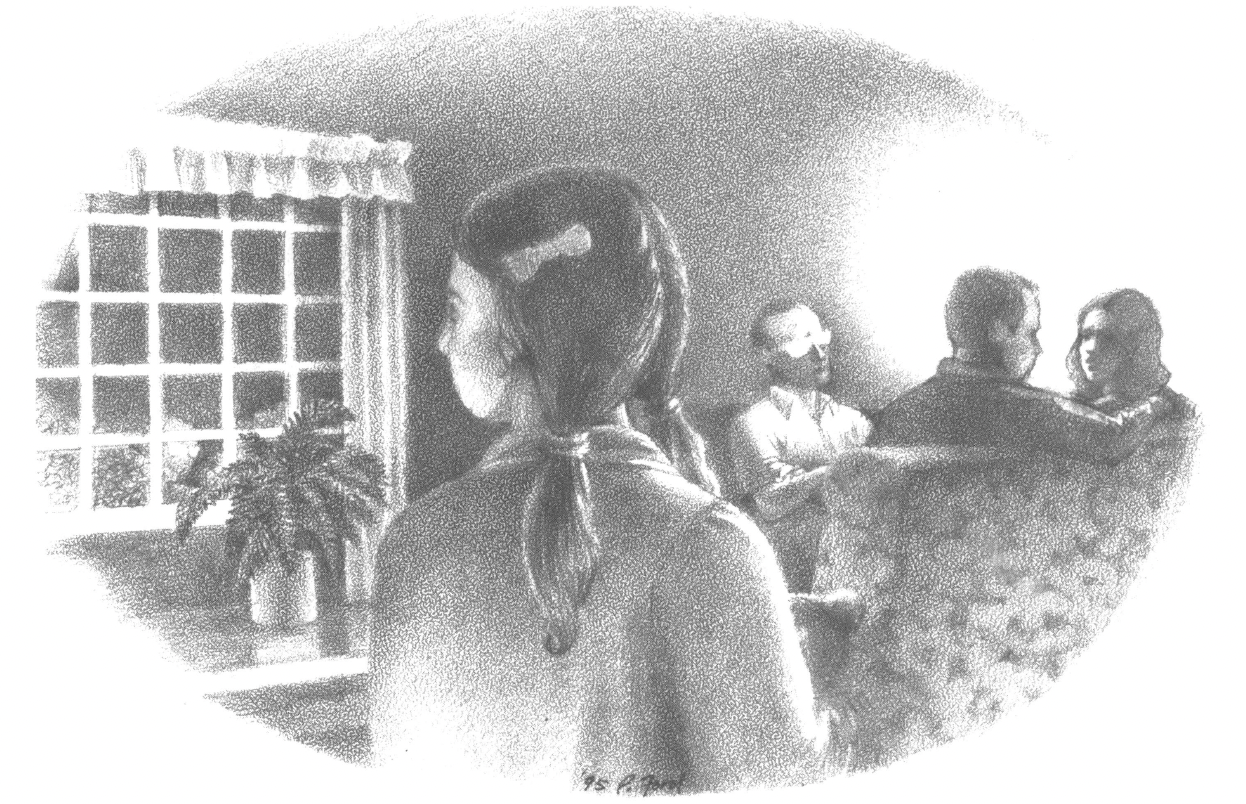

There were voices in the living room. My parents and Roger’s father. I heard him say, “His mother, it’s been hard.” I toweled myself off and dressed in the pajamas my mother had laid out. They were periwinkle blue. I followed the voices into the living room.

My parents were sitting with their backs to me. Roger’s father was on the couch. They were so intent on their words that they did not see Roger, crouched among the bushes, staring in the picture window at the end of the room.

He saw me and he smirked.

I looked at my parents, their mouths were moving. My father was saying, “I don’t think it’s necessary to involve the police.”

My mother turned on him in amazement. “The police? Of course not. I don’t want everyone in the neighborhood talking about this.”

Roger’s father nodded. The three of them talked on, caught up in their words, while Roger’s face watched through the window like a red and angry moon.

I knew then my parents could not protect me, because they thought their words were enough.

I felt as if I were shrinking, collapsing in on myself until I was as small and hard as the stones that lay at the edge of the pond, just beyond the water’s reach.

Tags

Janet Hearne

Janet Hearne is a free-lance writer in Johnson City, Tennessee. Her fiction appeared in the summer 1995 issue of Southern Exposure. (1996)