This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

When Carl Helwig toured a “state-of-the-art” incinerator near Long Island, New York, in 1988, he was deeply impressed. The high-tech, computer-monitored facility swiftly transformed stacks of used mattresses and junked refrigerators into electricity. Helwig watched in awe as the town turned other people’s trash into its treasure chest by importing waste and mining local dumps.

“It looked like a win-win situation to me,” says Helwig, a mechanical engineer. “I thought incineration was the answer.”

So did city officials in Helwig’s hometown of Slidell, Louisiana, 25 miles northeast of New Orleans. They welcomed the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) plans for a toxic waste incinerator in the middle of town. The incinerator would burn polluted materials from an EPA Superfund site nearby — an old wood-treatment plant on scenic Bayou Bonfouca. Incineration was a favorite method for treating creosote, an oily wood preservative suspected of causing cancer. The $112 million contract awarded to a joint venture of industrial giants Ohio Materials, Inc., and International Technologies, would pump money and jobs into the local economy.

At first Helwig did not worry about environmental damage. As a retiree of the oil field diving industry, “I thought Greenpeace was just a bunch of wild people running around plugging up plant outfalls,” he says.

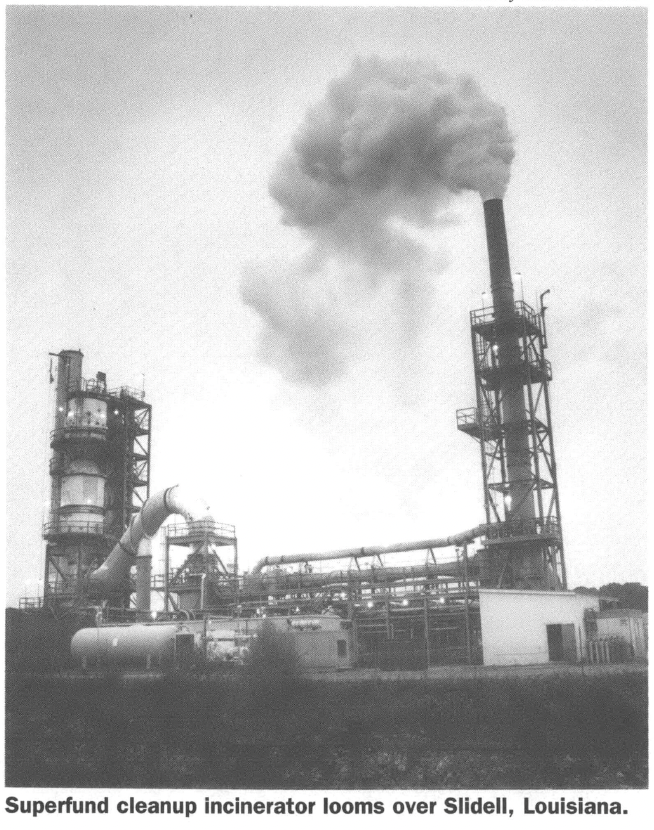

Bayou dredging began and the incinerator appeared in 1993, just off Front Street, a major city thoroughfare. Rather than the portable kilns that were described in early public meetings, changes in agency regulations and cleanup strategies had transformed the Bayou Bonfouca incinerator into a noisy 100-foot tall mammoth that residents complained looked like an oil refinery. The project had become the most expensive Superfund cleanup in the nation’s history.

“Until the incinerator went up, nobody really knew what was going on,” Helwig says. “There were no more public hearings, even though the scope of the project changed dramatically.”

Problems began to emerge. Lucy Tierney, a Slidell homemaker, often saw the incinerator’s steam plume drift over her house. She told the Slidell City Council that the incinerator reminded her of a dragon; it bellows, snorts steam and breathes fire. “I’m concerned that instead of just having water pollution, now we have air and noise pollution,” Tierney says. She also complains of respiratory problems.

Helwig began to worry about the safety of incineration when his nephew, an environmental engineer connected with the New York “waste-to-energy” incinerator, told him about dioxin, a byproduct of burning chlorinated compounds that has been linked with cancer, immune system deficiencies and birth defects. Helwig also learned about other unwanted byproducts of incinerators, including unburned heavy metals and new toxic chemicals that form as stack gases cool.

In the spring of 1994, Tierney, Helwig, and about 35 other concerned citizens revived a group that had originally formed to protest the expansion of a bleach plant in a low-income neighborhood — Slidell Working Against Major Pollution, or SWAMP. Helwig is now president, and Tierney is on the board of directors. The group teamed up with Tulane University’s Environmental Law Clinic and the Louisiana Environmental Action Network to sponsor a series of public discussions.

One of the first speakers the groups invited was Paul Connett, a chemistry professor at St. Lawrence University in New York who is considered an international expert on dioxin. “How many times have you been told that a well-designed incinerator poses no health threats? A scientific statement, right? Wrong!” Connett told SWAMP members. “Incineration is an experiment that you should not tolerate.”

Connett said he wouldn’t worry too much if the Bayou Bonfouca incinerator were burning only creosote. But, he said, the contaminated soil contained low levels of some heavy metals and chlorinated compounds that wouldn’t normally be associated with creosote. “If you have chlorine going in, you have dioxin coming out,” he says.

Slidell residents realized that no one had been critically monitoring cleanup plans. “Things are going on in your community that no one is aware of, is participating in, or is commenting on,” says Wilma Subra, a chemist and environmental activist from New Iberia, Louisiana, who listened to residents complain about nosebleeds, respiratory problems and strange odors at another forum. “You need to be part of the process at every step,” she says.

SWAMP members began poring over EPA documents in the public library, seeking technical information about exactly what the incinerator was burning and what was coming out of its stack. At an EPA open house in April, group members bombarded officials with questions about the operation’s safety.

Jim Ryan, an engineer and member of SWAMP, says that he was concerned that there was no continuous testing of the steam rolling from the incinerator stack. EPA project manager Bert Griswold replied that stack emissions were tested for hazardous materials during a trial burn and that other parameters, such as carbon dioxide, are continuously monitored. “There’s no equipment on the market to monitor that continuously,” Griswold says.

That wasn’t an adequate answer for SWAMP, which holds that even the best incinerators may not be good enough. “If an incinerator can’t be continuously monitored, it should not be used in a city,” Helwig says, to the applause of about 70 people.

SWAMP members decided that they needed their own technical expert to make sure that the site complied with safety standards. They agreed to apply for a $50,000 community grant from the EPA, which could be used to hire an independent scientist to interpret and monitor Superfund data.

SWAMP then began the process of legally incorporating, achieving nonprofit status, and filling out the grant application. The group received critical help and advice from Tracy Kuhns Sugasti, who had worked with a Texas group that shut down the incinerator at the notorious Brio Superfund site near Houston, Texas. When she felt her work was completed, Sugasti moved to Lafitte, Louisiana. She helped SWAMP, she says, because she couldn’t forget Brio.

After SWAMP received the grant, a more serious problem arose. Just one and a half miles down the bayou from the old wood-treatment plant, EPA was investigating two earthen pits at the defunct Southern Shipbuilding Corporation. The pits, filled with creosote, benzene compounds, pesticides, and other toxic waste from an old barge cleaning operation, were slowly leaching into the bayou.

The Slidell City Council, pleased with the operation of the current Superfund site, requested that EPA consider burning the shipyard waste at the Bayou Bonfouca incinerator. Councilman Richard Van Sandt said that combining the sites would save taxpayers millions.

Many community members were appalled, recalling an EPA promise that the incinerator would be dismantled as soon as the creosote cleanup was finished. Residents crowded an EPA open house in August 1994 where project manager Griswold sought to assure residents that the agency had not yet decided how to deal with the pits at Southern Shipbuilding. He said that EPA was considering a range of options, including incineration both on-site and at Bayou Bonfouca; soil washing, which would separate the pollution from the dirt for separate treatment; solidification, or encapsulating the waste; and bioremediation, which uses microbes to eat the waste.

But quietly at first, and then more openly, Griswold and other EPA officials began to favor hauling the waste to Bayou Bonfouca to burn it there. SWAMP members had pushed for bioremediation, but tests showed that it could take up to 10 years and may not work as effectively as incineration, Griswold said. Other options, such as taking the waste to a land farm near Baton Rouge, were slowly crossed off the list. Additionally, the Bayou Bonfouca cleanup could be completed as early as May — more than a year ahead of schedule — and agency officials wanted to make a decision quickly to keep that option open.

Combining the two sites would require “public approval,” but some in the community were already skeptical that their voices would be heard. SWAMP members requested that they be permitted to use their $50,000 Bayou Bonfouca grant to investigate Southern Shipbuilding as well, but EPA refused.

“It’s a done deal. There’s nothing anyone can do about it,” laments Mark Hardy, who lives near the Bayou Bonfouca incinerator.

SWAMP members grew increasingly fearful of burning the Southern Shipbuilding muck. Helwig only became more convinced of the dangers of incineration in December when he attended Dallas hearings on the draft version of EPA’s long-awaited dioxin reassessment. He listened to tale after tragic tale from people who lived in the shadow of incinerators and other dioxin-producing industries, such as paper bleaching plants.

“No conference ever got my attention more,” Helwig says. “Children being born deformed, miscarriages. We are paying a price for our modern conveniences, and that price is that a portion of our population is expendable.”

While EPA appears to be favoring incineration more and more, SWAMP gathered evidence from other Superfund sites to demonstrate that incineration was dangerous, and that there were alternatives. SWAMP found out that a proposed incinerator at the Texarkana Wood Preserving Superfund site had been delayed through the work of a group called Friends United for a Safe Environment (FUSE). After the EPA overrode public opposition and decided to burn the waste, FUSE teamed up with Arkansas Attorney General Winston Bryant and filed suit against the EPA, FUSE vice president James Presley says. Now, Presley said, EPA has promised to delay the cleanup until the federal Office of Technology Assessment completes a comprehensive study on the safety of incineration, and the results of that study are likely to include EPA’s own damning dioxin assessment.

Presley also told SWAMP about what he called EPA’s “smoking gun” — a North Carolina wood preserving site being cleaned up with a new technology that EPA itself developed. Called base catalyzed composition, or BCD, the method uses baking soda and heat to decontaminate soil. It even costs less than incineration.

So far, SWAMP’s findings have had little effect on the Slidell sites. EPA officials dismissed the Texarkana case, saying that the Slidell incinerator was very safe. Griswold also says that the waste at Southern Shipbuilding would not be well-treated by BCD, which was designed for chlorinated compounds.

SWAMP members don’t feel defeated, however. The group has gained some concessions. EPA spent about $4 million to add a muffler to quiet the noisy Bayou Bonfouca incinerator. EPA also brought out a mobile monitoring van one week in August to test for some air pollutants in the community, although that testing fell short of the permanent air monitors that SWAMP had demanded for nearby schools.

SWAMP members are determined to win at Southern Shipbuilding. They want to make sure that EPA investigates every alternative to incineration so that the Bayou Bonfouca burner will close as soon as the creosote cleanup is finished this summer.

“It might end up with signs and marching, the whole bit,” Helwig says. “We are adamant about [stopping] incineration.”

Tags

Sara Shipley

Sara Shipley is a staff writer with the Times-Picayune in Slidell, Louisiana. (1995)