This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

On any summer day, you can join bumper-to-bumper traffic snaking through the center of Cades Cove, Tennessee, on the western end of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Campers and tourists in air-conditioned cars stop traffic to take a photograph of a deer or to visit the Cable Mill for film and souvenirs. The unmistakable odor of brake fluid fills the air as you gaze across the open fields toward the dramatic wall of forested mountains rising above grazing cattle. Along the loop road, log cabins resting on neat green lawns — carefully labeled with family names — give you the impression that this popular tourist site was once, very long ago, a frontier community.

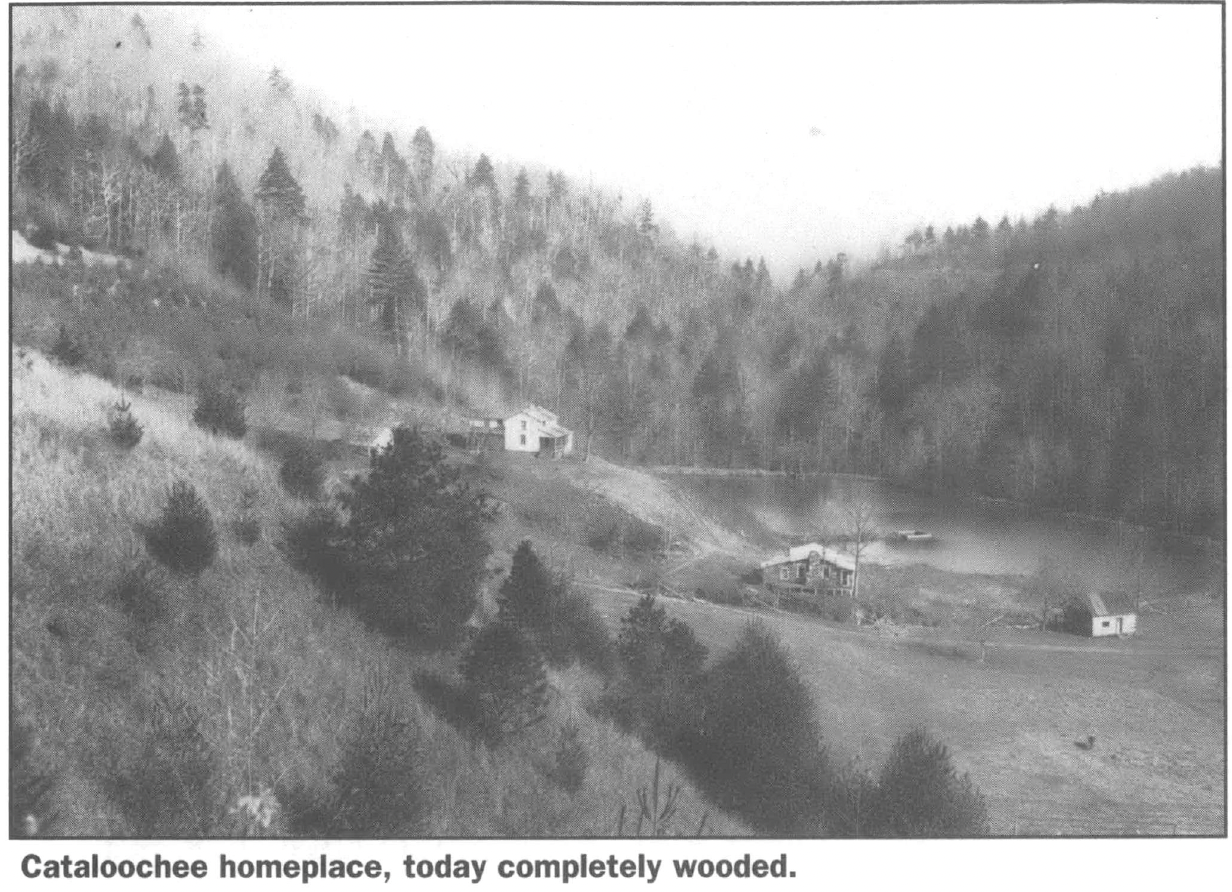

What most visitors don’t realize is that almost every watershed in the Smoky Mountains was once somebody’s home, just like Cades Cove. Until 1934, the Sugarlands, Copeland Creek, Cosby Creek, Big Creek, Cataloochee, Oconaluftee, Noland Creek, Forney Creek, and Hazel Creek were all etched into pasture, cornfield, wood lot, and homes. Sixty-odd years ago, this pastoral landscape, which extended up to 3,000 feet, supported an estimated 5,700 people.

To be sure, the Smoky Mountains residents did have ancestors who came as frontier settlers. John and Lucretia Oliver settled Cades Cove in 1818, and their grandson, John W. Oliver still farmed the same homeplace in the early decades of the 20th century, according to Durwood Dunn, author of a richly detailed community study, Cades Cove. Like many Smoky Mountains residents, John W. Oliver replaced the log cabin of his forebears with a framed farm house (others built less expensive “boxed houses”). Several farmers, including Oliver, ran guest lodges for hunters and fishermen. Many owned trucks and tractors, and at least one resident ran a gas station out of his general store.

Large farmers living in the fertile bottomlands raised corn and cattle for regional markets. Small upland farmers, who, in their words, “raised what we ate and ate what we raised,” made their living on small corn-and-vegetable gardens, plants gathered in the woods, and hogs grazed in the common woodlands above their homes. “We didn’t have to buy a thing, only just coffee,” Newton Ownby, a resident, told an interviewer in 1938. These rural Americans were not in any sense pre-modern or “backward,” but they lived a life intrinsically connected with the out-of-doors. Their hikes were excursions to find berries and dig ramps (a variety of wild onion); their camping trips involved fishing, hunting squirrels, or “salting” the cattle that grazed on the mountaintops.

Tourists Eye the Mountains

As the South urbanized, however, city residents longed for rural retreats, such as the very mountains the Smokies’ residents enjoyed. In the western United States, tourists promoted the construction of national parks out of public lands, but in the Southeast, almost all the land rested in private hands. Because the National Park Service did not yet possess land acquisition funds, Southern states purchased land or gained the power of eminent domain and then donated land to the federal government to create national parks. The first of these, the Great Smokies, resulted when the states of North Carolina and Tennessee bought or condemned 1,100 small farms and the property of 18 timber and mining companies. A few years later, Virginia took as many farms and mining interests to create Shenandoah National Park, and during the 1940s Texas dispossessed about 50 cattle ranchers to initiate Big Bend National Park.

Civic boosters from Knoxville, Tennessee, and Asheville, North Carolina, pushed a national park in the Smokies not for preservation so much as to bring their region publicity and income through tourism. In 1925, David C. Chapman, president of a drug company in Knoxville, founded the Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association to raise money for purchasing the large acreage needed for a natural monument. Chapman himself was so gifted in hyperbole that he almost single-handedly got the Southern Appalachian National Park Commission to list the Smoky Mountains as a potential site. Within months, the Conservation Association had attracted teams of journalists and travel writers to promote the Great Smokies.

Throughout the publicity campaign, Chapman and his promoters dodged the issue of whether anyone lived in the area where the new national park would be. They emphasized greedy corporate lumber companies, which were rapidly clear-cutting the ridge tops, and the destruction lent urgency to their cause. When rumors arose about condemning farms, Tennessee Governor Austin Peay traveled to the Smokies to reassure the permanent residents that their land would not be needed for the park.

At the same time, though, the omnipresent journalists who visited the region were charmed by the local residents. In addition to fantastic descriptions of scenery, newspapermen and women wrote about encounters with local people. “They are fascinating people these mountaineers,” wrote one journalist. “[T]hey are descended from pre-revolutionary backwoodsmen and still live in the eighteenth century.” Despite plentiful evidence to the contrary, writers described mountain residents living in log cabins without windows with families of 15 children, having “practically no contact with the outside world.” Chapman’s own group published a brochure claiming that farmers would “retain possession of their abodes within the park,” and “enjoy their new dignity, if such it is, of being objects of interest to millions of tourists.”

Whether the stereotypes were conscious or not, they certainly indicated a lack of concern for the future of those who considered the mountains home. An attorney for the lumber companies, James B. Wright, first raised the issue of forcing people off their land and started rumors among the mountain people that their lands could be “taken.” Knoxville newspapers ridiculed Wright, naming him the “foe of the park” for raising a cry of “spare the mountaineers’ homes!” When signs saying “We Don’t Want Our Homes Condemned” appeared in the Smokies, the newspapers blamed Wright for putting mountain people up to it. Although Wright probably did use concern for local people to aid his own interests, he put his finger on a problem park promoters didn’t want to face. The Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution states, “. . . nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Is a national park a “public use” important enough to override private property rights?

The Sentimental — uh, No, Grasping — Mountaineer

The first director of the National Park Service, Stephen Mather, did not think that park lands could be gained through condemnation. Assistant Park Service director Arno Cammerer, however, encouraged individual states to gain condemnation power and then donate the land to the federal government. When Cammerer drew a map of proposed boundaries for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, he included 704,000 acres and well over 10,000 people and their homes.

Wright, the “park foe,” joined several large landowners, local judges, and a state representative in opposition to the “Cammerer line” and the power of eminent domain that the state sought. A Knoxville labor publication came out in support of the park, but opposed condemnation power, because it “will put a hardship upon innocent people, yes, even upon unsuspecting people.” The editor also reprinted Governor Austin Peay’s promises that the mountain people’s homes “would be held sacred.” Park promoters knew what a volatile issue this could be, when another small publication declared, “We want the park. We must have the park. But we will not be party to visiting upon the people in the park area such a cold-blooded fate as that planned to deprive them of the only home they know.”

The major newspapers in the city, however, accused Wright and his group of “wrecking the greatest asset ever offered Sevier County.” One judge who opposed the park received threatening telegrams; all were treated with contempt by reporters. With the help of Wright, “park foes” struck a deal with state politicians. Large orchard and nursery owners around Gatlinburg and Wear’s Valley as well as the major hotels were left out of the “taking line.” The power of eminent domain could not be used on “improved property” unless the Secretary of Interior notified the park commission, in writing, that the land was essential. Even then, “all reasonable efforts to purchase the land” had to be exhausted before condemnation applied. With these changes, the state representative declared himself “staunchly for the bill.”

Park promoter David C. Chapman, for his part, continued proclaiming — long after the bill passed in both North Carolina and Tennessee — that power of eminent domain would not be used. Wright continued to needle the park promoters, and in 1929 he convinced the state legislature to investigate the buying procedures of the Tennessee Park Commission.

The North Carolina Park Commission, which was procuring lands in that state, had been staffed with Congressmen, a National Forest representative, and public officials from other parts of the state to ensure impartiality. Tennessee, however, appointed Chapman and other local individuals — including owners of a real estate firm that stood to profit from land sales — to the state park commission. Wright challenged Chapman’s power, the “propaganda” in the newspapers, and the method of land buying.

At one point, the investigators interviewed Cammerer, who explained why Cades Cove was “absolutely necessary” for the park: “You can’t put tourists on mountain tops. You must give them conveniences.” He dismissed talk about a “condemnation threat” against the mountain people: “Why call it a threat? It’s a power we already have.”

The investigating committee was unimpressed by Wright and those who testified and released a statement praising Chapman in April 1929. Chapman privately told people he was perturbed to have suffered this inconvenience. Newspapers echoed his disgust. Knoxville residents attended a “mass meeting” (actual number of attendees not given) denouncing the “sob stuff’ Wright offered. One citizen attacked Wright for protecting the “sentimental mountaineer,” who, in reality, was “grasping at golden opportunities to enlarge his pocketbook with gains from vast golf courses, snobbish hotels, and hot dog stands.”

Although a few families did benefit from the new park economy, most community members did not want to move. According to Alie Newman Maples, the younger people wanted to sell, but older, more established farmers did not. “Like anyone who has a home where you’re happy, you hate to give it up and sell it,” she explained. Winfred Cagle, who grew up in Deep Creek, said, “At that time people didn’t know anything about parks. They thought it was awful, to just drive people out of their homes like they drove the Indians out at one time. People didn’t understand about preserving a forest. . . . They thought they were just being drove out.”

Taken from “My Mountain Home,” a poem by Louisa Walker

They coax they wheedle

They fret they bark

Saying we have to have this place

For a national park

For us poor mountain people

They don’t have a care

But must a home for

The wolf the lion and the bear

Building a Mountain Out of a Condemnation

The Tennessee Park Commission filed its first major condemnation suit in July 1929. The year before, when park land buyers offered Cades Cove landowner John W. Oliver $20 per acre, he asserted that “real estate here sells for $40 to $50 per acre.” One of the largest landowners in the Cove, Oliver held over 337 acres of fine bottomland. Until it became clear that the park commission wanted to take his land, Oliver actually deplored the destructive logging practices and supported the national park. The farmer first appealed to the land agent’s conscience. “When this is all over,” Oliver wrote, “you will want to remember that you acted perfectly square with people who have been dispossessed of their homes in order that city people might have a playground.”

Well-known to Knoxville residents, Oliver’s predicament brought the mountain residents some of their first positive media attention. “While this territory is miles from any railroad connections and is beyond the reach of telephone and telegraph, many of the farmers residing within the coves are progressive,” reported the Knoxville Journal, “in many instances the farms being equipped with power tractors, lime pulverizers, and other modem machinery.” This more realistic description came too late to stop the overwhelming media impression created with the help of the same newspaper that these were poor mountain people in need of “uplift” — or removal.

Cade’s Cove resident Oliver challenged the state’s right to exercise the power of eminent domain on behalf of another sovereignty, the federal government. Although the Blount County Circuit Court agreed with Oliver, the Tennessee State Supreme Court overturned the decision. The court saw no reason that the power of eminent domain “be exclusively the necessity of the particular sovereignty seeking to condemn.” This case and a similar one lost by Mack Hannah of Cataloochee in North Carolina courts, greatly discouraged others from defending their homes and communities. In the words of Zenith Whaley, a resident of Greenbrier, “With the big dog gone, they knew they couldn’t handle the bear.”

Sharp traders and those who could afford lawsuits got a more favorable price for their land. Mack Hannah, for example, was heartbroken not to retain his home, but the “jury of view” did assign $11,000 to his 152-acre farm. Oliver, who contested the “jury of view” price, received $17,000. Public officials complained bitterly that such prices were too high, and as a result the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) later sought more sweeping condemnation powers (See “Damming the Valley,” page 30).

But Hannah and Oliver’s prices were neither exorbitant nor even representative of what happened to most mountain residents. In the Big Creek community, for example, small farmers received approximately 1.6 times the tax valuation of their property. An estimated 300 tenant farmers received nothing at all, and neither tenants nor landlords were compensated for relocation nor aided in the removal process in any way.

The year 1929 turned out to be a poor one for converting land to cash, and many people, including Cagle and Whaley’s fathers, lost their money in bank failures. “[People] felt pretty well when they first got to buying,” said Ownby, who moved to Wears Valley. “By the time it was done they hated [the park], all the people pretty generally hated it.” In addition to losing investments in bank failures, some former residents took a lease in part consideration for the price and then found it difficult to buy land with the remaining capital.

Their 15 Minutes of Fame — Enough Already!

A special arrangement ordered by Congress allowed elderly people to remain on their land for the rest of their lives. Much as the park promoters predicted, the “lifetime lessees” became celebrities to the tourists, who flocked to their doors. “But [older people] couldn’t be happy up there all by themselves,” said Lucinda Ogle, who grew up in Greenbrier but lives in Gatlinburg today.

The most famous lifetime lessees, the Walker sisters, lived together in Little Greenbrier. Although one sister sold her poems to the tourists, the women eventually got tired of the steady stream of visitors — sometimes hundreds a day — interrupting their work and asked park officials to take the sign down that identified their home.

The same lifetime lease agreement also provided a “loophole” for 72 summer home owners to retain their property in the Elkmont area. Here, the park provided police protection and maintenance crews until 1993, when the summer home community was finally forced to leave. David Chapman, the “father of the park,” owned a summer home in Elkmont under this arrangement. When controversy arose over his special privilege, he transferred the lease to a relative living in Panama.

Although the Great Smoky Mountains was a “preserve” for Nature’s wonders, early tourists clearly preferred pastoral, human-created scenery. Before the land even came under the jurisdiction of the federal government, visitors flocked to Cades Cove. Because of this popularity, the first park superintendent reluctantly agreed to continue “meadowland maintenance,” or mowing, to prevent the forest from invading the fields. During the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps crews rehabilitated old log cabins and built split-rail fences to make the site look more “historic.” If the dispossessed farmers did not dismantle framed or box houses as they left, park rangers torched the “modern-looking” buildings.

Other communities, such as Copeland Creek, Noland Creek, and Deep Creek, were completely cleared, and the land slowly returned to forest. In some cases, a foundation or chimney remains to this day. In a few places, the only sign that this was once a homesite is a clump of jonquils that appears each spring where a resident had planted them. “The memories that I have of living in the mountains really mean so much to me,” said Maples, who lives in Gatlinburg. “You don’t know too much about the mountains until you get with someone who used to live up there. You’ll find that the love they have for the mountains overcomes any that they have for land they got anywhere else.”

Not until 1965 did the National Park Service gain funds to acquire land without the help of states, and the agency is now authorized to use condemnation on a case-by-case basis. According to Howard Miller of the Land Resources Division, the Park Service prefers to buy land from willing sellers and tries to limit condemnation to property where the land is threatened, such as the 400-acre tract near Manasses Battlefield, where an investor wanted to build a housing development. During the 1970s, however, the agency condemned a high percentage of 35,000 half-acre lots purchased to create Big Cypress in Florida. Miller does not believe, however, that a complete removal of permanent rural communities, as was done in the Smokies and Shenandoah, could be accomplished today. “There’d be an outcry,” he said. Miller, whose grandparents lost their homes for the creation of Shenandoah National Park, hopes that visitors will remember and appreciate the sacrifice of those who had to leave these beautiful places.

The tourists who crowd Cades Cove today, I suspect, don’t always realize this melancholy note to a historic site. Like the earliest visitors, they want to escape a hectic schedule and imagine a simpler, back-to-the land existence. When I first started researching the Smokies six years ago, I resented the traffic, the video recorders, and the brightly dressed people gawking at the scenery. I felt they did not appreciate what the land once meant to the former residents here. Over the years, however, I have developed a wistful fondness for the mass of humanity that visits the cove each day. I see them as sojourners, pilgrims in Winnebagos and Explorers, searching for their lost rural heritage on a national park loop road.

The Cherokees and the Park

As many people know, more than 20,000 Cherokees were forced to leave the Southeast in 1838, because of the Indian Removal Act.

Marched at gunpoint, they walked to Oklahoma and more than one-fourth died along the route, known as the Trail of Tears. A group of Cherokees living in Western North Carolina were allowed to remain, in part because they had separated from the Cherokee Nation and could claim a different legal status. They were joined by other Cherokees, who escaped into the mountains when the soldiers came. It took almost 100 years for the members of the Eastern Band to gain the full rights and privileges of citizenship guaranteed residents of the United States.

When the Great Smoky Mountains was created in the 1920s, an official at the National Park Service drew a “takings” line on a map that included all of Big Cove, the most traditional community on the Quallah Boundary. A bureaucratic brouhaha followed, as the Bureau of Indian Affairs did not believe that this would be an appropriate transfer of authority. This time the Cherokees were spared, ironically, because the two agencies did not agree on what was “best” for them. Today, tourism is the number one industry in Cherokee, North Carolina, the Southern entrance to the park.

Tags

Margaret Lynn Brown

Margaret Lynn Brown just received her doctorate from the University of Kentucky. She has spent the past six years studying the removal of residents for the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Fontana Dam. Her book, Smoky Mountain Story, will be ready for publication later this year. (1995)