This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

Protection of private property rights was built into the United States Constitution. But historically, most government condemnations — or land-takings— fell on those with few resources to protect these rights. Still, this constitutional protection ensured at least some protection for small landowners.

In recent years, a new interpretation of the Constitution has emerged, and conservative republicans have embraced it. Law professor Richard Epstein in Takings: Private Property and the Power of Eminent Domain describes the idea: Any time the government imposes regulations, it, in effect, “takes” your property rights.

As author Ron Nixon shows in this article, large landowners are using this argument to claim that they should be compensated any time federal regulations to protect the environment cost them money. The so-called property rights movement does not protect small landowners from aggressive government or corporate takings. Rather, it seeks to gut legislation, such as the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act.

Charleston, South Carolina, real estate developer David Lucas has been a busy man since his landmark private property case before the U.S. Supreme Court. For the past three years, he has testified against environmental regulations, spoken before groups such as the Society of Environmental Journalists, and raised money to build a national group called the Council on Private Property Rights.

Lucas is positioning himself as the poster boy for a new “property rights movement” — or the “wise use” movement — which claims to advocate less government regulation and greater rights for property owners. “I’m just the tip of the iceberg,” Lucas said in a recent interview. Indeed, USA Today estimates that as many as 500 such groups already exist across the country. In the past year, 32 states have introduced bills advocated by these groups. Mississippi, West Virginia, and Tennessee have all passed so-called property rights legislation, which requires governments to pay landowners if a regulation affects the value of their property.

“I like pristine areas,” Lucas says, “I like to walk on the beach, but the question is: Are we going to ruin thousands, maybe millions of people across the country, do damage to our economy, lose jobs, and lose productivity because of regulations?” This “us versus the government regulators” attitude gets to the heart of the property rights movement. Proponents seek to expand greatly constitutional protection for wealthy corporations and individuals who want to escape responsibility for the environment.

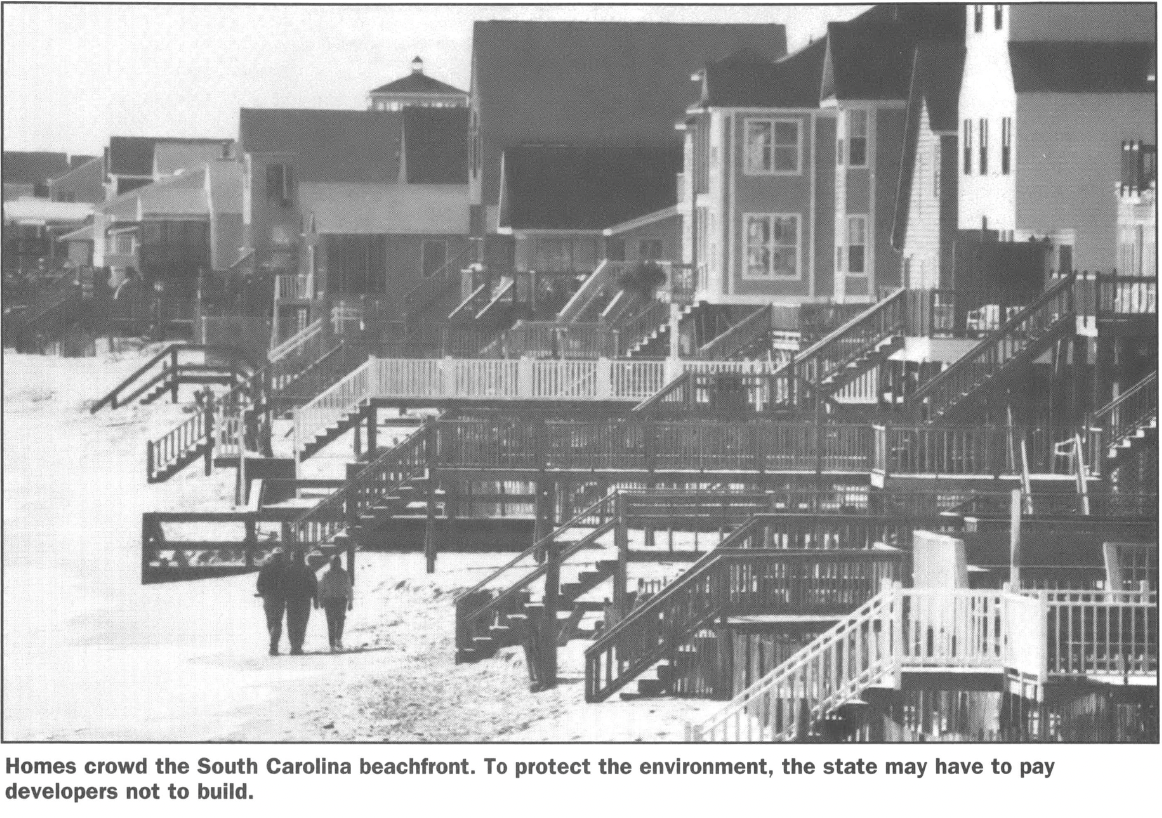

Lucas began his crusade in 1986 when he bought two pieces of property on the South Carolina coast. He intended to build a home for himself on one of the lots and sell the other. In 1988, however, environmental advocates pressured the South Carolina Assembly to pass the Beachfront Management Act to protect the fragile, rapidly eroding coastline. The legislation barred Lucas from building on his property. He sued, and the state granted him a variance so that he could build. The variance still involved restrictions, however, and Lucas alleged that his land had lost all economic value.

Under the Fifth Amendment, governments are prohibited from taking private property for a public use, such as a road, without paying “just compensation to the owner.” Lucas’ lawyer interpreted the decreased economic value of his land as a “lost property right.” A lower court accepted this argument and awarded the developer damages. But the state Supreme Court reversed the decision, so Lucas took his case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

By a six to three vote, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Lucas’ expansion of property rights. Writing for the majority, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote, “As we have said on numerous occasions, the Fifth Amendment is violated when land use regulations do not substantially advance legitimate state interest or deny an owner economically viable use of his land.” This opinion represents a contradiction in the new Supreme Court, which prides itself in stepping away from judicial activism, or broad interpretations of the Constitution.

Capitalizing on the momentum of the Lucas case and endorsed by the Republican “Contract with America,” property rights advocates are pushing for “takings” legislation across the nation. Such legislation would make court cases like Lucas’ unnecessary, according to Glen Sugameli, an attorney with the National Wildlife Federation. “Essentially, [under takings legislation] we have to pay someone not to pollute or not to destroy someone else’s property,” says Sheila Holbrook-White, member of the Alabama Sierra Club. “If these bills pass, we’re going to see the regulations we’re fighting to hold onto now, gutted.”

Property rights advocates claim that they are just trying to battle a hopelessly bureaucratic government. “These bills are designed so that when government regulation goes too far, the property owner is compensated,” says Bob Scott of the South Carolina Forestry Association. “Landowners should not have to bear the full burden of protecting a bird if it’s in the public interest.”

How far is too far? The M & J Coal Company of West Virginia last year claimed that it lost “property rights” when the Office of Surface Mining (OSM) attempted to enforce mining regulations. Although company practices resulted in ruptured gas lines, collapsed highways, and destroyed homes, M & J argued that OSM violated its “rights” by attempting to correct the situation. In another case, a chemical company in Guilford County, North Carolina, sued the county government when they were denied a permit to operate a hazardous waste facility. The company said that because the area was already contaminated, the only economic use of the property would be a hazardous waste facility. To deny them the income from hazardous waste denied their “property rights,” they claimed. Lower courts threw out both cases, but new legislation and the Lucas decision by the Supreme Court to back it up could make a difference. “If ‘takings’ bills were enacted, there could be a different result,” said National Wildlife Federation attorney Glen Sugameli.

“We’ve been telling Congress for years that federal agencies are stealing private property when they come in and tell owners, ‘that’s now a wetland, and you can’t build a house on it,’ or ‘we’ve found a spotted owl in your tree, and now you can’t do anything with your land,’” says Margaret Ann Reigle, Chairperson of the Fairness to Landowners Committee in Cambridge, Maryland. “With the Republican sweep of Congress we’re going to get a fair hearing.”

Private property rights advocates, such as Reigle, deny that they want to curb the “legitimate” authority of government. “We’re not looking to undo zoning laws, local land use, or any nuisance laws,” says Jon Doggett of the Farm Bureau in Washington, D.C. “But what we’re looking for is the addressment of the very important issue of how much authority the federal government has in telling you what you can and can’t do. And at what point does the regulatory activity become so egregious that there is a violation of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution?”

In spite of such comments, there is no reason to think that this legislation would be limited to undoing red tape. In a letter to the governor of Alabama, State Attorney General Jimmy Evans wrote that such legislation would have “a devastating effect” on the ability of the Alabama government to exercise the most basic police powers. “The practical effect,” he argues, “would be to end effective zoning, environmental, health regulation, and land use planning in the state of Alabama.”

“The goal of this property rights movement is to paralyze the government or bankrupt it,” adds Louie Miller, a member of the Sierra Club in Mississippi who has lobbied against the state takings bills. “They have basically bastardized the Fifth Amendment.”

The enormous potential cost of the legislation has helped marshal some powerful opposition to it. According to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, these laws could cost between $10 and $15 billion and would threaten the ability of the government to regulate business. For these reasons, both the National League of Cities and the National Conference of State Legislators have adopted resolutions opposing takings legislation. A letter from 28 state attorneys general states that the laws are based on the “dubious principle” that the government “must pay polluters not to pollute, pay property owners not to harm their neighbors or the public, and pay companies not to damage the health, safety, or welfare of others.”

“The irony is that these bills costing billions of dollars are being introduced by people who were elected as fiscal conservatives,” comments Holbrook White.

Whatever the cost, the biggest beneficiaries of the movement are large corporations. Observers confirm that groups such as the Maryland Fairness for Landowners Committee, the Wetlands Awareness Committee in Mississippi, and the Alabama Stewards of Family Farms, Forest, and Ranches, are little more than fronts for corporate interests. An investigation by the environmental group Greenpeace found that corporate and industry trade organizations provide the bulk of the funding for property rights groups. Exxon, Monsanto, Dupont, Coors, oil and gas interests, lumber companies, the American Farm Bureau, and others not only contribute money but also place board members in these organizations. Although the Farm Bureau claims that property rights legislation will help rural residents, investigations by Prairie Fire, a farm research group, show that less than half of Farm Bureau members are actually farmers.

Property rights groups also benefit tremendously from the service of conservative legal institutions. The Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF), with headquarters in San Francisco, filed an amicus brief (friend of the court) in the U.S. Supreme Court on behalf of Lucas, the South Carolina developer. According to its newsletter, the group also assisted the counsel for Lucas in preparation of oral arguments. Since it was founded in the 1970s, the PLF has been a vocal opponent of environmental regulations, rent control, and civil rights laws.

Another group that supported Lucas in his case was the Institute for Justice, the same group that got President Clinton’s nominee for assistant attorney general, Lani Guinier, smeared as a “quota queen.” In the wake of the Lucas decision, the Institute for Justice vowed “to employ this favorable case precedent in future challenges to government intrusion on the rights of property owners.”

In addition, other conservative groups, like the Defenders of Property Rights, have assisted the growing property rights movement in the South. Defenders of Property Rights, a Washington, D.C.-based organization, was founded by Roger Marzulla, assistant attorney general under the Reagan administration. Marzulla and his wife Nancie prepared a pamphlet for the South Carolina Forestry Association called 10 Reasons to Support the South Carolina Private Property Rights Act. During this legislative session, the Forestry Association is using the pamphlet to create a favorable environment for a takings bill. Defenders of Property Rights also helped draft takings legislation in Mississippi.

Yet another resource for the property rights movement is the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a conservative think tank. ALEC provides “model legislation” for the 2,400 “pro free enterprise” legislators it claims as members. Funded by Philip Morris, Coors, Texaco, and other large corporations, ALEC has sent legislation to politicians across the South.

“The guys who are pushing this legislation are not known for their concern for protecting the public or small business people,” comments Bill Holman, a lobbyist for the Sierra Club in North Carolina.

On the other hand, warns Dana Beach of the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League, property rights advocates should not be dismissed as merely a front for corporate interests. There are bona fide grassroots constituents for some of these bills, according to Beach. “In many areas, support comes from people who have never had to deal with land use issues,” Beach says.

Other advocates are property owners and businesses that have for years complained of restrictions they feel are imposed on them by regulations. “We’re reasonable people,” says Kim English, of Mars Hill, North Carolina, who fought the state’s 1991 watershed protection law. “We’re not anarchists. We try to live under the rules. But some of these [environmental] rules are excessive.”

At the same time, most people still want the environment and their health protected from polluters. According to a 1994 Times-Mirror poll, for example, 51 percent of people surveyed thought regulations to protect endangered species had not gone far enough. A full 76 percent thought that regulations to prevent water pollution did not do enough to protect them; only 4 percent thought water pollution regulations were excessive.

To revise laws that might be overly complex requires “a detailed analysis,” according to Beach, “to decide which laws should be enacted, modified, or stricken.” In the meantime, property rights advocates offer an appealingly simple alternative: do away with regulation altogether.

No one denies that there are legitimate concerns in the struggle to balance the needs of society with those of the individual property owner, comments an editorial in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution. Arguments being put forth by conservative think tanks and business groups, though, represent “pure hypocrisy,” the editorial writer maintains. “Those who scream the loudest about government regulation are usually those who benefit the most from government investments.”

The example cited by the editorial is the taxpayer-subsidized National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Established by Congress in 1968, the original intent of NFIP was to steer development away from risky areas. Instead, a 1982 General Accounting Office (GAO) report found that the NFIP has provided a “safety net” for shoreline development. Under the program, the average policyholder pays only $252 per year for flood insurance and can make unlimited claims without a rate increase. According to another GAO study, the program operated at a deficit of $650 million between 1978 and 1987. To bail out the nearly bankrupt program, Congress appropriated more than $1 billion to NFIP during the 1980s.

“Without this kind of support from taxpayers, takings proponents like Lucas would not have been able to build in a coastal area,” says Louie Miller of the Mississippi Sierra Club.

To control costs, the 1993 Congress tried to limit the availability of federally backed insurance, but the National Association of Homebuilders campaigned against cuts to the program. The Homebuilders, also a major proponent of property rights legislation, actually argued that limits on subsidized insurance would diminish property rights. Without subsidized insurance, developers couldn’t get loans to build in sensitive areas.

“It would certainly be more expensive if people had to buy flood insurance based on risk,” says Walter Clark, a coastal law specialist at North Carolina State University. But more expensive insurance, Clark points out, also would have the positive effect of discouraging development along the ocean front, “where it shouldn’t be taking place, anyway.”

Another major advocate of property rights, the logging industry, benefits enormously from government subsidies. Because lands managed according to state forestry laws receive tax exemptions, private landowners dodge billions of dollars in property taxes every year. In the state of Alabama alone, for instance, the forestry industry saves more than $77 million through tax exemptions. When asked to comply with voluntary standards for buffer zones along streams to prevent erosion, though, the Alabama Forestry Association objects. “Laws and regulations that purport to protect the environment,” argues the Alabama trade association, “cause economic hardship that amounts to a violation of the Constitution.”

And farm industry groups, who also advocate private property rights, collect billions of dollars in subsidy programs each year. A Pulitzer prize-winning series by the Kansas City Star on U.S. Department of Agriculture subsidies revealed that these programs are rife with abuse by corporate farmers. In one case, an individual farmer collected nearly $5 million by claiming fraudulent subsidies.

Government subsidies for farming, forestry, and development industries could be described essentially as a “giving,” argues Dana Beach of the South Carolina Coastal Conservation League. “If taxpayers have to compensate property owners when their property is devalued by government regulation, then why shouldn’t property owners compensate the public when the government increases the value of their property?”

The bottom line, Beach said, echoing one of the founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, is that private property rights are, in fact, a creation of the government and society. Franklin wrote, “Private property is a creature of society and is subject to the calls of that society.” James Madison, the father of the Constitution and the principal author of the Fifth Amendment, realized the necessity of prohibiting certain activities on private property. The Fifth Amendment does not give property owners permission to harm others, or, in the words of Madison, remove from “everyone else the like advantage.”

This is also not the first time in history that conservative groups have tried to hide from community responsibility under a cloak of property rights. For example, when the federal government passed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Heart of Atlanta Motel sued under the Fifth Amendment. The motel claimed that the federal government violated their “property rights” by forcing the facility to allow entrance to black customers. This strained interpretation of property rights, however, was rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court.

“The new debate about takings attempts to impose a radical interpretation of the Fifth Amendment that would curtail the government’s ability to protect the common good,” says Dr. Joan Brown Campbell, General Secretary of the National Council of Churches of Christ. Campbell testified before a recent Congressional hearing on takings legislation. “It would take us back to an age of excessive individualism where the interest of the greedy override the public’s well being,” she says. “While we respect the legitimate rights of individuals, we at the same time expect every property owner to respect the covenants that we have made as a society to work for the common good.”

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.