“Irrational NIMBYs” vs. the Technocrats

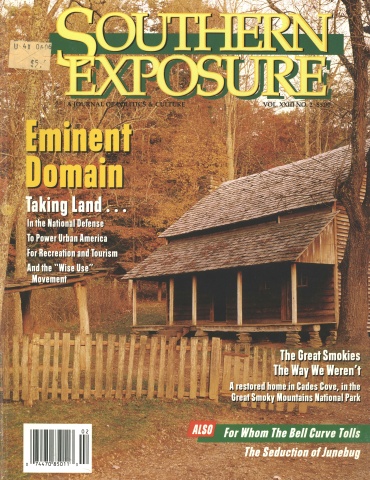

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

On any sleepy day in a rural community, they can show up . . . the folks in business suits and Italian loafers, who explain why they 1) need your land for a highway, a power line, a pipeline, or a lake, and 2) why opposing them is hopeless.

The corporation intent on benefiting from this “progress” will bring with them a university “study team” or “big name consultants,” who show, with the help of studies sponsored by the corporation, the benefits of the project. Slick researchers will then produce computer-generated geographic information system (GIS) maps, which explain (in four-color) the advantages of your land as the “least impact” location for their project. Before you know about it, local officials have granted the power line or pipeline company the power to take land through eminent domain. They can condemn and take property. And once they have condemnation power, it’s too late.

As citizens begin to object to the loss of their property, these technocrats dismiss them as irrational “NIMBYs” (Not in My Back Yard!) who won’t, unfortunately, accept their loss as being best for the “public good” — the economy, the community, and even the environment. In this way, technocrats with a strong profit motive effectively paint small landowners as the “selfish ones.” They have rationality on their side, and you, in effect, are arguing with a computer.

So it’s not a fair fight, to be sure. This unequal conflict between the citizenry and those who would use government power to further private interest has been with us since the Industrial Revolution. Computerization simply delivers a new and powerful weapon into the hands of corporate interests, but this same weapon can also provide an opportunity for rural citizens to question the need and location of such projects.

Based on my experience as an attorney, this is what you need to do when those guys show up with their computer-generated displays:

First, don’t be intimidated by the technology or by your lack of comparable maps. Dig into the subject, read up on these maps, and educate yourself on how to “walk the walk and talk the talk” of the technocrats. Most importantly, use your knowledge of the on-the-ground landscape to question their fancy maps.

Second, don’t assume that the maps are correct. The fundamental problem with computerized studies is that the impressive analysis and fancy display capabilities of a computer program usually outstrip data collection and verification. How did they get their information? Data collection is often costly and requires tedious fieldwork, which is unattractive to planners, landscape architects, and geographers. They will pretend that their incomplete and inaccurate data is correct and manage to fool themselves along with the public. This map does not show my pond, you tell them, and where have you placed our community meeting center on your display? “Ground truthing,” the process of comparing the results of computer-generated studies to the “real world” on the ground, will often reveal substantial errors that can slow up if not derail the entire project.

Third, remember that computer displays and maps are meaningless without knowledge of the methodology. Find out how they defined and weighted each factor in their analysis. Computers work in numbers, so somebody had to turn factors, such as land use, history, quality of life, and other values, into a number. How did the computer program define “least impact?” How much “weight” did it give agricultural use, a residence, or a church? Did the computer program consider aesthetic concerns? Despite the importance of methodology, technocrats will attempt not to reveal these critical facts. Insist on details in writing — a description of the methodology — for it is in these details that the prejudices and biases of the study will be found.

Fourth, use every resource — human, technical, and financial — to first identify issues not considered by the power line company or highway department. A very common mistake of citizen groups is to over-research issues identified by their opponent. Collateral attacks from unexpected directions can take advantage of overconfidence and lack of flexibility in the management structure of large institutions. Did they consider, for example, that the power line will have to go through an old-growth stand in a National Forest, which contains several endangered species? With the demand for documentation in environmental impact processes, a poorly done computer study may look impressive but quickly collapse when challenged on the right basis.

Fifth, develop and carry out your own integrated strategy. In struggles over development, citizens must battle political, technical, and legal fronts all at once. You must educate other members of the community, put pressure on local officials, find someone to give technical and legal advice, and keep up good communication with all members of your group. This can’t be done alone. Bring together everyone you know who will help.

Sixth, pick your paid assistance carefully. Often the first reaction of a community is to hire a lawyer and thereafter concentrate on raising money for fees and expenses. Unless the attorney is attuned to technical and political issues, however, he or she may not be able to accomplish all that you hope. When confronted with a technically oriented administrative process, a better and less expensive first-hire might be a geographer, a landscape architect, or other technical consultant. For example, if you need to question an environmental assessment, a person with credentials in biology might help you more than an attorney.

On any sleepy day in a rural community, they are liable to show up. . . . But if citizen groups can avoid the intimidation and confusion that comes with computers and business suits, they can beat them at their own game. By working smarter and understanding the strengths and vulnerabilities of computer studies, the “natives” can effectively challenge the “cannons” of modern technology.

Tags

Jim McNeely

Jim McNeely, an avid backpacker and Appalachian trail hiker, is a country lawyer from West Virginia. When AEP tried to build a power line across the mountain that he calls home, he became involved in representing Common Ground. We asked him to tell us what he’s learned so far, or what advice he would give to communities facing similar threats. (1995)