Eminent Domain Carves Up a New South

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

em’ i•nent do•main the right of a government to appropriate private property for a perceived public use, usually but not always with compensation to the owner.

Last summer my neighbors dolefully watched as Oglethorpe Power carved up a piece of their property for a high-voltage power line. With the power of eminent domain behind them, this private company purchased lands from their Rocky Mountain power plant to Atlanta, slicing Northwest Georgia into a wedge and pretty much erasing the Kinneys’ backyard in the process. First a timber contractor clear-cut the trees up Turkey Mountain, then the power company erected an enormous fence along the road ways. Finally, the towers arrived. Tied together by taut lines, they marched up and down the landscape like gargantuan creatures from outer space.

Some people sued; some people were reimbursed for the “inconvenience,” but most of us were left wondering about the long-term effects of these unwanted invaders. In addition to generating electromagnetic fields (EMFs), the power lines and towers changed forever the long unbroken ridge residents here recognize as home. One of our friends mourns a magnificent stand of pink ladyslippers bulldozed with the trees. Others worry about the herbicides the company will use to keep the corridor free of undergrowth and what that will mean for their springs, their wells . . . and their health.

Unfortunately, this story is being repeated through the rural South. As the Southern states race to industrialize and improve their infrastructures, the accompanying power lines, pipelines, and highways have begun to crisscross the countryside, aimed at major urban centers. All of this is possible, I discovered, because the power of eminent domain — once the exclusive privilege of government — is now being wielded by large corporations for private profit.

This special section of Southern Exposure looks at how the use of eminent domain has been expanded by government and private interests over the past 70 years. Although scholars and journalists have discussed in detail the role of federal spending in the creation of a New South, most have ignored the use of federal authority to force residents off their land. Although much has been written about the rise of a Sunbelt serving the residential preferences of a new middle class, the effect of industrializing cities on the surrounding rural environment receives little attention. Although anyone could be affected by corporate use of eminent domain, conservative politicians have distracted public debate on this important topic by advancing a sideways discussion of the “takings power” of environmental regulations and a construed reading of the Constitution.

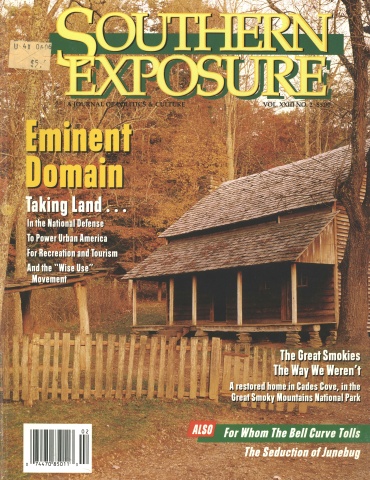

The U.S. Constitution guarantees private individuals “just compensation” for property taken or condemned for federal road construction and other “public goods.” In the 20th century, a National Forest system was interpreted as a “public good” for which eminent domain could be used. Later, national parks became a “public good” for which government might usurp private property. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) received the power of eminent domain for the “public goods” of flood control and navigation, though the agency used it primarily to generate electric power.

Today, the undemocratic use of government power is being extended to private power line, pipeline, and communication companies for the creation of their transmission corridors. Whereas TVA received the power of eminent domain under an act of the U.S. Congress, a private electric company can now take land through the simple administrative process of a state utility board. Not surprisingly, the people most likely to lose their property without any benefit of public process are those like my neighbors, who do not have the financial resources to resist.

Tags

Margaret Lynn Brown

Margaret Lynn Brown just received her doctorate from the University of Kentucky. She has spent the past six years studying the removal of residents for the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Fontana Dam. Her book, Smoky Mountain Story, will be ready for publication later this year. (1995)