This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

Honey, I’ll tell you. I’m an old woman and I’ve been through a lot to keep my land. I’ve been through the Depression and near starvation to hold on to what my family passed to me. You see my aunt over there, she’s in her 90s and she comes to all these meetings with me. We don’t intend to let them take our property. We’ll fight to the death to keep our land, because we don’t have anything to live for without it.

— Thelma Boothe

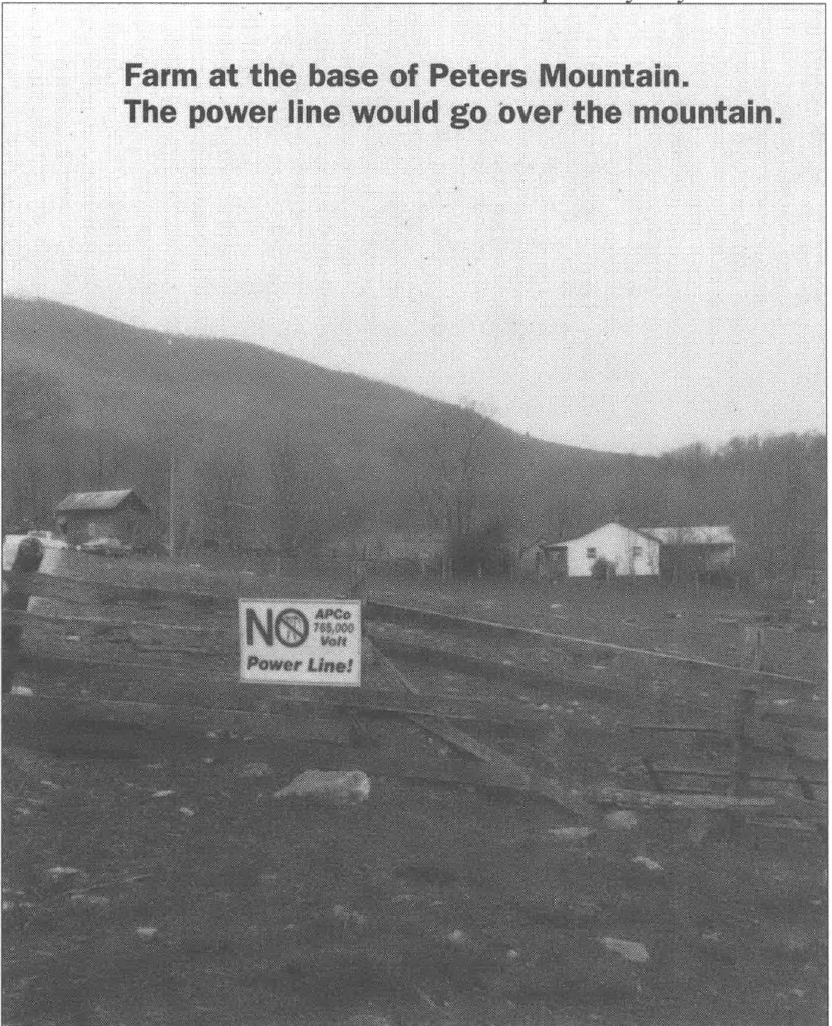

If you’ve ever traveled along Peters Mountain or through the New River Valley of West Virginia, you’ll understand something about the powerful sense of place that Thelma Boothe feels. Small farms scattered below long forested ridges look like scenes from a 1920s postcard. A general store and gas station mark the center of each small community, and people here still sit on their front porches at night. The gentle beauty of the place makes you believe that a truly good way of life is still being lived somewhere in the world.

For the past five years, though, Boothe and her Monroe County neighbors have engaged in a fierce battle over who has the rights to this corner of southeastern West Virginia: the home or American Electric Power (AEP). Since 1990, AEP, through its subsidiary Appalachian Power Company (APCO) has tried to gain the power of eminent domain in order to take land for the construction of a 765-kilovolt electric transmission line right through Mercer, Summers, Raleigh, and Monroe counties in West Virginia and on to Roanoke, Virginia.

The corridor — the company’s term for the swath of land it wants to use — not only involves taking people’s land, but, in some cases, destroying the environment and, as a result, landowners’ livelihoods. The $5 billion dollar-a-year corporation wants to sell cheap electricity from its power plants in the Midwest to East Coast markets. Power from the line will not benefit West Virginians at all.

Transmission line struggles such as this one are likely to increase. Both sides are lining up. In the coming decades, power companies will increasingly engage in “wheeling and dealing” electricity (a phrase used by the industry) across state lines. The National EMR Alliance, an organization that tries to help local groups, has grown to 350 grassroots affiliates (including ones in every state in the South) in just four and a half years, according to representative Cathy Bergman. As the Southeast continues to be the fastest-growing region of the country, battles between rural landowners and corporations serving urban industrial centers are likely to grow.

The struggle in West Virginia is unique, however, because in this case rural communities have resisted a multinational corporation’s attempt to gain power over the landscape. But residents have become discouraged about the length of their fight and the ease with which this private company can still gain the immense power of eminent domain. Yet these southeast West Virginians are determined to protect their land and culture.

The controversy started for Mary Pearl Compton in 1990, when she received a letter about a public meeting in Hinton, West Virginia. Compton, who represents the 26th district (Mercer and Summers counties) in the West Virginia legislature, drove to Hinton, where the power company had set up a huge display about the power line. The meeting troubled Compton because almost no one showed up for it. As she drove home that night, she grew deeply worried. “I believed that people didn’t know about the meeting, or they would’ve been there,” she remembers.

When she got a letter about another “public” meeting at the Mercer County courthouse, Compton made sure 15 people she knew showed up. “It was the same speeches and everything,” she recalls, but this time the people who attended expressed their distress.

Bob Zacker, a Monroe County potter and jewelry maker, was covered with wood shavings that night when his neighbor drove up and said he needed to go to the meeting. “I’ll never forget the date — November 11, 1990,” he says, because the meeting forever changed his life. “The information was cleverly disguised, but we figured out they wanted to build the largest power line in the U.S.A. right through our county.”

Over the next few months, every county in this corner of West Virginia organized as a group. Zacker helped start Common Ground (Monroe County), and across the ridge in Mercer County residents organized Citizens Against the High-Voltage Powerline. A third group called itself A Coordinated Voice for Summers County.

The X-Letters

Neither AEP nor APCO yet had a permit from the West Virginia Public Utilities Commission. Such a permit from a state administrative office would give them full power of eminent domain, the right to “take” people’s land for the project. Although it still had no such power, the company proceeded to send residents letters which declared that their land would be taken and how much they would be paid for it. Thelma Boothe received such a letter, which included a map crossing out large portions of her property. The “x letters,” as Boothe and her neighbors now refer to them, gave everyone a shock and inspired many other members of the community to join the grassroots organizations.

“They say that they will pay you for the piece of land they use,” explains Jeanette Justice, a schoolteacher in Mercer County and member of Citizens Against the High-Voltage Powerline. “But taking a piece of my land is like coming in with a carpet knife and slicing a one-foot square in the middle of my living room rug. When they do that, they’ve ruined the whole thing. Who wants to own — or buy — a house or land with a hole in it?”

Each group began circulating petitions and educating themselves about the power line company and its plans for their community. Joe and Arna Neel, Monroe County farmers and founders of Common Ground, traveled with a group of their neighbors to Floyd County, Virginia, to look at a similar power line built there. They interviewed farmers like themselves and discovered that the voltage was so strong that residents there had to ground their tractors. When Floyd county fanners get on a roof to paint or maintain it, they are often mildly shocked. The most distressing part of the story, said Neel, was that most of them first heard about the power line after the company had the power of eminent domain, “after it was too late to stop the bulldozers from rolling over their land.”

Once a corporation gains the power of eminent domain from state authorities, there is almost nothing that can be done, according to Jim McNeely, a lawyer who began working with Common Ground. “People need to get involved in the administrative procedure, because otherwise their rights may expire there,” says McNeely. It is not unusual for the only “public meeting” held by power companies to be the kind of poorly announced proceeding held in Hinton, he explains.

“How could this happen in a democracy?” asks Amy Cole, a leader in the Border Conservancy, another community group. Both the United States and the West Virginia Constitutions guarantee that private property cannot be taken by the government without “due process” and “adequate compensation,” but how does a private company so easily gain this power? “It seems so un-American,” Cole comments.

Giving Away Our Sovereignty

Since the Industrial Revolution, corporations have sought to gain the powers of government while retaining the privileges of individuals. In West Virginia during the late 19th century, the legislature granted extremely broad powers to railroads, which took land to construct lines for the coal companies. “Giving the rights of government to the railroads was very controversial at the time,” says Richard Grossman, head of the Program on Corporations, Law, and Democracy.

Yet, Grossman points out, today few people are challenging the right of private gas, telephone, and electric companies to take land for their own purposes. “If we, the people, give corporations this power, to what degree are we giving away our sovereignty as a free people? And if we give them power,” Grossman adds, “to what extent should [these corporations] continue to be responsible to the public interest?”

To keep their land, the community groups in West Virginia found that they have to tackle such heady questions. The answer to their dilemma was not found by simply hiring a lawyer or getting a powerful politician to help them. They had to become directly involved in the political process.

The groups gathered 10,000 signatures on petitions and traveled to the West Virginia legislature to gain political attention for their cause. With the help of Compton, they passed House Concurrent Resolution 41 in 1992, which expressed concern about the economic, cultural, and environmental impact of the proposed high-voltage power line on the community. HCR 41, the community group’s first victory, helped send a message to the state Public Service Commission that laws and regulations protecting West Virginians from such projects should be enforced.

The groups also began collecting information about why the AEP/APCO power line was not necessarily in the public interest. Bob Zacker, whose land would not be taken by the power company, was especially disturbed about the potential environmental damage to the beautiful valley in which he lives. Peters Mountain, which the corridor would intersect, is a 61-mile limestone karst containing more than 1,000 small springs. This fractured limestone purifies the water of two Monroe County mineral spring companies, New Mint Springs and Sweet Springs Valley Company, as well as that of a Roanoke-based company, Quibell. Sweet Springs has won three of the five last international testing competitions held in West Virginia.

Because AEP would have to maintain the power line corridor by spraying herbicides on the land, the groups worry about the effect on the mineral springs, the health of area residents, and the endangered species that live in the Jefferson National Forest through which the corridor would pass.

“It’s going to hurt the water-bottling business on Peters Mountain. This water is supposed to be the best in the world,” says Bill Mitchell, a school bus driver from Summers County. “Those boys over there are going to be real upset about this power line and the spraying that’ll go on if it’s strung up.”

“I’m 49 years old, and I’ve been concerned about the environment most of my life,” says Zacker, who moved to the valley 20 years ago to raise his family. “But when it’s right in front of you, you have got to do something. That’s what consciousness is. If folks don’t want corporations to steal their private property and their public rights, then they’ve got to take a stand.”

Zacker became the executive director of ARCS, a bi-state group dedicated to coordinating the efforts of 10 different county groups opposing the power line. ARCS, which gets its name from the luminous glow resulting from a broken electric current, received a small three-year grant from the Catholic Church’s Campaign for Human Development in Washington, D.C.

Zacker and the community members researched whether or not the power line was really needed and who stood to benefit from it. “Why does a small state like West Virginia need one of the largest transmission lines in the world running through it?” asks Zacker. The groups discovered that AEP could gross as much as $100,000 an hour on such a transmission line and increase their profitability by 10 percent. “We have all the power we need right here in the mountains,” says Zacker. “Why should we suffer because AEP wants to make more money transferring power from the west to the east?”

As Bill Mitchell, a retired railroad engineer, put it, “It’s nothing but an electric interstate in the sky that’s going to dump cheap Midwest electricity into the East Coast market.”

But Mitchell takes the issue one step further. Not only did AEP stand to gain, but because the cheap Midwest power could depress local coal producers, the West Virginia economy could suffer, according to Mitchell. A member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, Mitchell helped develop a resolution against the power line from that group as well as one from the United Mine Workers.

Strange Bedfellows; the Eco-NRA

Because of all this organization and communication, the power line controversy has caused some unusual coalitions to form in West Virginia counties. The treasurer of Common Ground, for one, is a member of the National Rifle Association, and another prominent member is on the board of the National Committee for the New River, an environmental group. “I usually hate environmentalists,” the treasurer reportedly said. But now they are united by the same purpose.

The National Committee for the New River proved to be a powerful ally. The power company proposed an alternative corridor for the power line, which would pass across the lovely New River valley just south of the New River Gorge, which is administered by the National Park Service. Community groups, along with the National Committee for the New River, gained the support of other environmental groups, including the Sierra Club and Ducks Unlimited, which passed resolutions against the power line. In 1992, legislation was passed to place the section of the New River upstream from Bluestone Lake under study as a potential Wild and Scenic River.

For several years, the National Committee for the New River has been trying to get this designation, which would make a power line pretty much impossible to take through the land. Because of the power line fight, many community members finally saw the importance of the designation and participated in federal hearings about the river. Patricia “Cookie” Cole, a Monroe County farmer who painted “Just Say No to APCO” on her barn, testified in 1993 before a Congressional hearing on the federal Wild and Scenic River status: “Since 1990, I’ve been fighting a power line. But what I have learned is that we can’t wait on a threat to appear: We must get our mountains, our rivers, our landscape, and our way of life the recognition and protection they deserve. Our mountains, our rivers, our land . . . have all become endangered species which we must fight to protect.”

These gargantuan political efforts finally paid off on May 10, 1993, when the West Virginia Public Service Commission dismissed the AEP/APCO high-voltage power line application. But the company did not by any means give up. Instead, they hired a New Jersey consultant to help write an environmental assessment of the power line corridor and planned a new round of public meetings. In 1994, the company held another round of public meetings in southeastern West Virginia, this time armed with maps. Back in 1991 when AEP had constructed the original siting map for the power line corridor, the company hired landscape architects from the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and West Virginia University. Virginia Tech researchers collected data about the geography of the region, and West Virginia University generated computerized, four-color maps of the region. With the “objective science” of university studies behind them, the experts offered a slick presentation of why the power line had to go through southeastern West Virginia.

“The burden is on rural communities to fight corporations with tens of thousands of dollars to spend on presentations,” complains McNeely. “With the prestige of the universities behind them, it’s easy to be persuaded.” But the community groups had done their research. They knew they had to do more than say they didn’t want their land taken; they needed to question the basis on which the siting had been done. The place was packed, according to Compton, and people questioned almost every premise under which the map was created. How much weight was given to churches, they demanded to know. What values were given to agricultural land in the computer program? The communities of Waiteville and Zenith were not even on the maps, someone else pointed out, and the corridor went right through the Zenith general store, where Common Ground held its meetings. “It was obvious that to AEP these communities were just an empty spot on the map,” said Compton.

At one public hearing, an unknown community member stood up and said, “Let me get this straight. If we had divided up our land for profit, a subdivision or something, you wouldn’t have considered us [taking that land]. But because we kept our land together, protected our homeplace for a hundred years, you’re coming right at us?”

The company did not convince anyone in the community that the power line was in their best interest. In fact, since then, AEP has also been turned down by the Virginia Public Service Commission, which was influenced by the decision made by West Virginia. At present, the power company is trying to obtain the right to cross the Jefferson National Forest, and the community groups are trying to get the National Forest Service to hear their concerns. After five years, they don’t expect any fight to be easy.

It is clear in West Virginia that a battle is emerging over the balance of power in this country. For real change to happen, citizens must challenge what Richard Grossman calls the “judicial edicts beginning in the 1880s,” which granted corporations far-reaching constitutional powers, such as the use of eminent domain, and protection, such as free speech. He also reminds us that regulating and controlling corporations is the responsibility of the citizens through the voice in their legislatures. To win the battles of eminent domain, citizens must insist that legislatures, judges, and corporations be accountable to the communities they affect.

On Peters Mountain, where residents hear the roar of the land, feel the pulse of its energy, and see its spectacular beauty, this is about more than a piece of property: The land is a living symbol for the spirit of the place and people. As “Cookie” Cole put it: “On Peters Mountain people believe that only God has eminent domain!”

Tags

Charlotte Pritt

Charlotte Pritt worked as a consulting community organizer with groups in West Virginia fighting the AEP/APCO power line. In 1992, she ran as a grassroots candidate for governor of the state, and in six weeks, with a $115,000 budget, nearly unseated the incumbent. This fall, she will be the Democratic candidate for governor of West Virginia. (1995)