This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 2, "Eminent Domain." Find more from that issue here.

With the exception of federal armies led by Grant and Sherman, no other government institution has matched the impact of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) on the region of the Tennessee River. Between 1933 and 1945, TVA gained some 1.3 million acres from private hands and displaced an estimated 82,000 people from their homes in order to build 16 hydroelectric dams. That’s an area larger than the state of Delaware and a population that in 1930 was the same as North Carolina’s largest city, Charlotte. In just 12 years, the agency turned America’s fourth largest river into a series of slack water reservoirs and transformed the physical landscape of the middle South.

At its creation in 1933, TVA received a sweeping mandate from Congress to improve navigation and flood control, to contribute to the nation’s defense, and to carry out whatever measures it deemed necessary to promote “the economic and social wellbeing” of the people living in the river basin. Generating and selling electricity was mentioned only peripherally by New Deal legislators, but the agency quickly made this its chief focus. To expand the regional market for electric power through the construction of hydroelectric dams, the agency made heavy use of eminent domain — the taking of private property for “public use.”

Would Farmers Undermine Progress?

“There is a great temptation to develop a kind of Alexander-the-Great complex among those of us who are carrying on the project,” wrote David Lilienthal, the TVA board member in charge of land policy. “We are constantly looking at maps with a great area marked on them and blocking out this and that on these maps.” Although the Army Corps of Engineers proposed a series of low dams in the Tennessee Valley for flood control and navigation, Lilienthal’s grand designs favored a multipurpose high dam system. The high dams required much greater population removal, but they would fulfill the board’s desire to create the pre-eminent electric utility in the South.

Agency officials such as Lilienthal were well aware that removing 1.3 million acres and 16,500 families would have a “detrimental” effect on local communities and would force even larger numbers of farmers off the land. To TVA officials, loss of community was an acceptable price to pay for modernization. In fact, planners and government sociologists held that too many Southerners were living on the land and that most of the South’s economic problems could be laid at the doorstep of a “surplus farm population.” To remedy this, TVA sought to make these people available for employment in industries attracted by the cheap electric power.

Historians Michael J. McDonald and John Muldowny have studied the first TVA project, Norris Dam, which displaced over 3,000 families and transferred some 153,000 acres into government hands. Rather than a “surplus farm population,” they argue in TVA and the Dispossessed, some of those people living in the Norris Basin were “returnees.” During the early 20th century, residents of farming communities migrated to regional centers, such as Knoxville, Tennessee, to work in textile mills. When the Great Depression hit the mill town, they returned to rural areas like Norris to live with relatives or to work on an old homeplace, where they could at least raise enough food to survive.

With the clout of President Roosevelt behind it, however, TVA blunted all opposition. The federal government, after all, was pumping large amounts of capital into an historically neglected region, and holding up massive projects for the sake of rural communities seemed tantamount to undermining Progress. Once World War II began, TVA cloaked itself in the mantle of “national defense,” and resistance, in this case, looked downright unpatriotic.

Still, in these early years, TVA needed to justify both itself and the usefulness of its dam projects to Congress and the American public. It was obliged, therefore, to paint a dim picture of the farms it was going to flood and residents of the region. In films, books, and speeches, TVA pointed to poor farming practices and erosion as the chief culprits in the region’s poverty. Poverty and environmental problems had more to do with lumber and mining industries, which extracted natural resources and deserted the mountains. But TVA depicted the valleys as “wasted land, wasted people,” as if farmers themselves were to blame. TVA’s stock newsreel image — the grizzled hillbilly farmer scratching out a bare subsistence — made farmers look so backward that federal intervention would be their only hope.

TVA Likes High-Priced Spreads

For the most part, the bottom lands that TVA sought to inundate were the highest-priced farmland in the region. River bottom farmers practiced the most technologically advanced soil-conserving methods of agriculture on land made rich by the silt left behind by the river’s seasonal floods. The bottom lands around the mouth of Duck River, Tennessee, produced some of the highest corn yields in the South. TVA’s determination to erect high dams to produce the maximum amount of hydroelectricity meant a much higher cost to Valley residents in terms of flooded farmland.

To achieve these ends, Congress gave TVA free rein to exercise the power of eminent domain. Whereas the Department of Justice handled condemnation proceedings for other agencies, Section 25 of the 1933 TVA Act empowered the agency to conduct its own land condemnations. By statute, TVA could decide which lands were necessary, use its own appraisers, and make a non-negotiable offer to landowners. If an owner refused to accept this one-time offer, his property was condemned and a “declaration of taking” was issued that allowed the Authority to take immediate possession. Despite the fact that nearly all challenges to eminent domain in the United States went before a jury, TVA was specifically authorized to forego jury trials as a means of determining fair compensation. During the Norris project, the head land buyer was somewhat reluctant to exercise these broad powers, and some landowners were able to haggle over the price of their land. Landowners who protested the valuation on their property were sent to U.S. District Court, which appointed three commissioners for each reservoir area to investigate and determine property values. Their decision could be appealed before three federal district judges, and, ultimately, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Concerned about the few people who received higher payments for Norris basin lands and the slow land-buying process, TVA took action. The Authority hired attorney John Snyder, fresh from large-scale condemnation work in New York City, with orders to obtain reservoir property as quickly and cheaply as possible. To eliminate any price haggling, Snyder explained that he did not wish to favor “sharp traders” over those farmers who might not be able to conclude a favorable sale of their land. “We work on a nontrading basis, a price is set and we buy at that price or we condemn,” he said simply. This non-market approach certainly expedited land acquisition, but it tended to ignore not only the owner’s assessment of land value but also the sales value the property would command from a private buyer.

TVA’s own economists estimated that the agency’s condemnation power enabled it to obtain land at roughly 60 percent of what it would cost a private buyer. The actual number of properties that TVA had to condemn was small, around five percent for the largest projects, because landowners soon learned that Snyder’s policy would be enforced. A study of TVA appraisals, however, shows cursory field work, a questionable method of pricing land by soil type instead of evaluating the individual tract, and land buyers’ general unfamiliarity with local agriculture. Only after 1959 did TVA appraisers consider such criteria as earnings potential, replacement value, or comparable sales value — all standard measures for appraising real estate.

TVA’s land agents followed a divide-and-conquer strategy in their approach to landowners. They first dealt with out-of-state banks and insurance companies, which were anxious to unload farms they had foreclosed on during the preceding decade. Next they sought absentee owners and those whose farms were heavily mortgaged. Then, in the words of TVA Chairman A.E. Morgan, agents were instructed to “go around and pick up all the land from the people that would sell easy, pick that up at a low price.” By buying off large sections of the community, the agency increased the pressure on the remaining farmers, who most likely felt a deeper attachment to their land. The agency bought much of its land at Depression-era prices based on appraisals that had been done in the mid-1930s when farm commodity and real estate values were at all-time lows. By the time displaced owners went to look for another farm, they faced a rising land market. Prices were being driven upwards by wartime inflation and TVA’s own land-buying. This “extraordinary market” made it difficult for those who lost a farm to buy another at a comparable price. Since displaced farmers preferred to stay in the county near their families, they piled onto the remaining marginal lands, thereby exacerbating the very problem that TVA was supposed to solve.

In addition, the land-buying program did almost nothing to assist residents in relocation. With a budget in the tens of millions of dollars, TVA devoted just $8,000 and 13 staffers to resettlement efforts. Almost as many tenants as landowners were evicted by TVA, and for this class of “adversely affected” farmers, the agency assumed even less obligation. “It is the very necessity of the tenants having to go which will make them find their own solution to their difficulties,” wrote one TVA staff member.

Farmers Already Saw the Light

Although TVA retained unprecedented powers of eminent domain and commanded a remarkable public consensus, landowners did confront the agency. Congressional hearings in 1938 and 1942 focused on the problems and complaints arising from TVA’s land policies. Those who testified challenged steamroller buying practices and the fact that lakes inundated fertile land with water and left the uplands intact. As one resident of Birchwood, Tennessee, asked, how could people “make a living” after bottomlands were taken? “We already have light, we have modern conveniences,” he added, challenging the notion that TVA would in any way benefit farmers.

“We have been shoved back off of the fertile river lands. We are losing our best citizens. The lands that are left us by TVA are not fertile,” J.W. Davis, a farmer displaced by the Chickamauga project, complained before Congress. Davis thus raised the troublesome question of “secondary losses.” In the Valley region, farmers often lived upland from their most fertile fields. By flooding only the productive bottom land, TVA drastically reduced the value of the remaining tract. The agency stuck to a strict legal interpretation of its liability, however. For Davis, this meant remaining on a small acreage upon which he could not make a living.

Few farmers could afford the travel and expense of litigation, particularly in the face of a large and well-financed government legal staff. “I am 71 years old, I am not going to be here long, and I don’t want to get involved in any lawsuit,” J.M. Gass of Meigs County, Tennessee, told Congress. “I am going to sign your contract, knowing at the time I am not getting a fair deal.”

Senator George Norris, the Nebraskan who sponsored TVA’s legislative mandate, criticized those who complained about their appraisals for bringing negative publicity to the agency. In his journals, Lilienthal called those who contested TVA’s offers “greedy swine,” who were “stirring up evil.” Lilienthal argued against jury trials, which, he said, would add $20 million to the cost of land-buying. Because of strong kinship networks in the South, he claimed, it would be hard to find an impartial jury in the region.

Congressional leaders also criticized the fact that TVA acquired considerably more land than was actually flooded. The agency’s “heavy purchase” policy cleared families from a wide belt around the reservoir, so that TVA could experiment with malaria control, practice land conservation, or promote lakeshore industrial development. Outcry against this land-grabbing policy forced the agency to forego the “heavy purchase” policy in 1942, but by then land for most of the dams was already purchased. When land above the high water mark became an expensive management problem, the Authority transferred the property to other agencies, such as the Department of Interior.

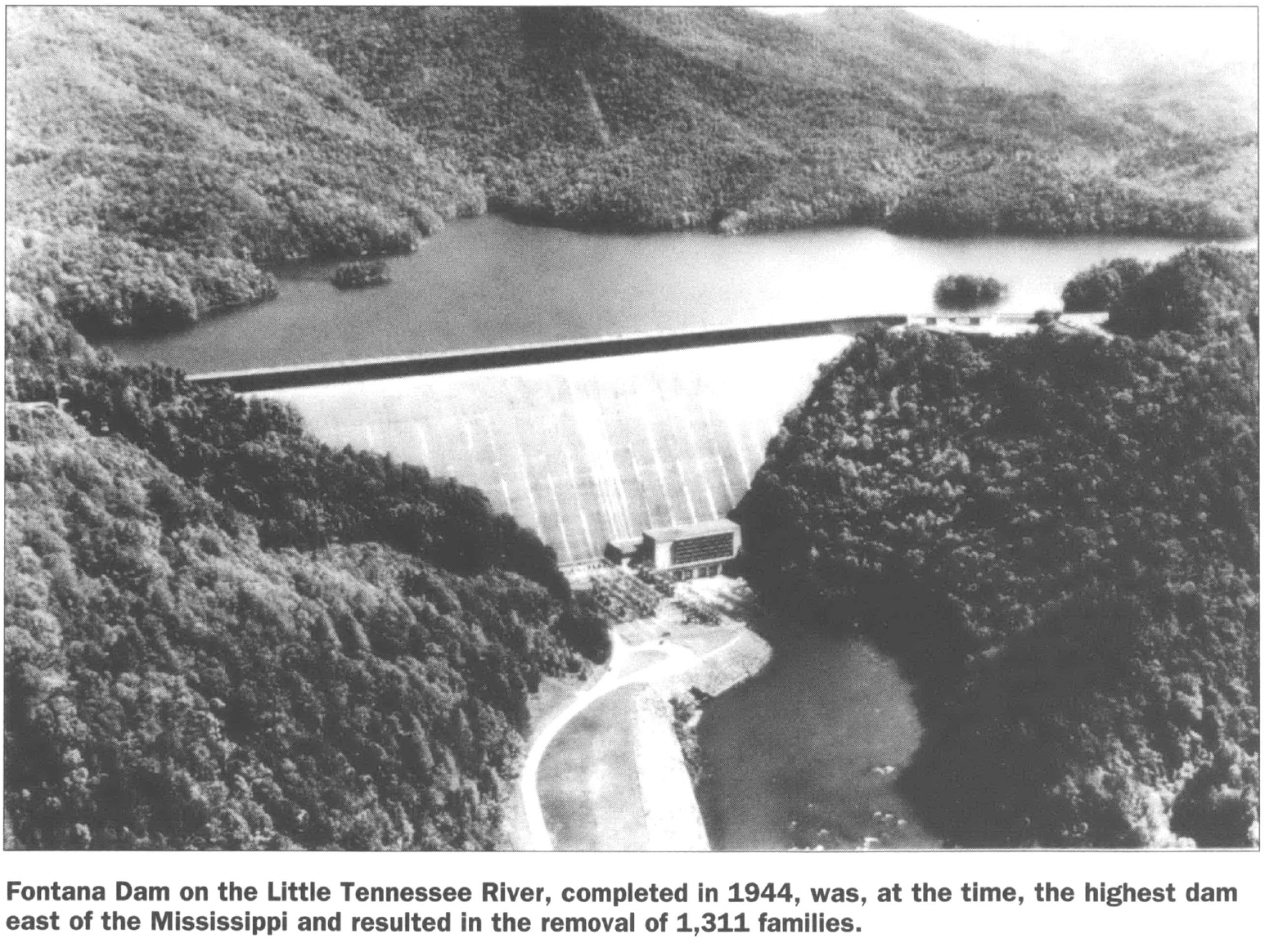

Six farmers from the Hazel Creek Valley of North Carolina challenged broad powers and the “heavy purchase” policy during the construction of Fontana Dam. Because floodwaters would isolate Hazel Creek farms and force the government to construct an expensive road, TVA condemned the remote valley with plans to donate the land to the adjacent Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The angry farmers took their case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Welch vs. TVA, rendered in 1946, the Court sanctioned TVA’s self-regulating system of land acquisition. In the unanimous decision, written by Justice Hugo Black, the court endorsed TVA’s land-buying procedures. TVA’s actions were all directed, the judge wrote, toward “the general purpose of fostering an orderly and proper physical, economic, and social development of [these] areas.”

Snail Darters Try to Save Farmers

After World War II, TVA found it harder and harder to justify aggressive land-taking in the region. During the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, however, the agency promoted two projects that would bring them the greatest public criticism they were to receive. Land Between the Lakes, a 170,000-acre “national demonstration” in recreation and “resource development,” removed 949 families from three Kentucky and Tennessee counties already gutted by the Kentucky and Barkley reservoirs. Built near the river’s mouth at Paducah, Kentucky, the dam flooded the most land of all. Because of the gentle gradient of the lower Tennessee River, the backwater of the Kentucky Dam reached 185 miles into Alabama, took 316,000 acres, and displaced 2,600 families.

Between 1967 and 1979, TVA became embroiled in controversy over another project, the Tellico Dam on the Little Tennessee River. The media played up a last-minute legal maneuver by environmentalists, who tried to stop the dam by protecting a potentially rare species of fish called the snail darter. The story untold by newspaper headlines was that Tellico Dam also required flooding 43,000 acres, dispossessing 350 families, and destroying acres of historic Cherokee archeological sites.

For both these projects, TVA expanded its mandate from electricity and national defense to include building a huge public recreation area and a “planned” community for industry. Residents refused to roll over just because TVA said it needed more land to demonstrate conservation practices, or, in the case of Tellico, build “Timberlake,” the “model” Appalachian city. Litigation dragged on for years and finally gave the agency a media black eye for running roughshod over the very people it was supposed to help.

Jean Ritchey, a Little Tennessee River resident, fought to keep her home for 10 years. Her drive to resist TVA was intensified by the fact that her father lost his property in 1940 for the Watts Bar project. After years of court battles and watching the media focus on the “snail darter issue,” Ritchey watched in November 1979 as construction crews bulldozed her house and barn into a hole and buried the remnants. “I always thought eminent domain was for building something that was going to make everybody better off, things like roads and schoolhouses,” Ritchey told a reporter. “They took our land for development.” Development, she might have added, that never materialized. No industry chose to locate on the shores of Tellico Lake, so the planned community was not built. Chastened by the storm of controversy, TVA has not pursued land acquisition since the Tellico Dam.

Clearly, TVA’s unquestioned power in the South lies in the past. Today, most Southerners regard it as an overgrown government bureaucracy, but as long as it keeps utility rates down, they don’t think much about it one way or another. The agency’s legacy continues, though, as TVA can claim significant impact at the international level. Long admired by central planners and foreign technocrats, the agency has served as a model of big-scale engineering for other countries. “What we have done in the Tennessee Valley, we can do elsewhere,” President Harry Truman said in 1948. Dam projects undertaken by Turkey, India, Ghana, Egypt, Brazil, China, and the old Soviet Union dwarf in size the removals done in the Tennessee Valley. In many cases, these governments displaced millions of inhabitants in order to modernize rural river valleys.

By dispossessing river bottom farmers and promoting a high-cost, high-tech vision of development, TVA played a major role in curtailing small farm operations in the Tennessee River Valley. As planners predicted, the agency was responsible for enormous out-migration. In the Kentucky reservoir region, for example, some counties lost up to 32 percent of their population between 1940 and 1950. After dam-building was complete, high unemployment typically persisted and sometimes worsened in reservoir areas. TVA, in short, failed to live up to its own dictum — “to leave the area in which a reservoir is built and the people who lived in the area at least as well off as they were before TVA entered the picture.” Heavy out-migration and a drastic decline in the number of farmers, in the end, seems a curious legacy for an agency supposedly committed to revitalizing a farm region.

Tags

Wayne Moore

Wayne Moore, Ph.D., is an archivist at Tennessee State Library and Archives who teaches history at Tennessee State University. His dissertation, “TVA and Farm Communities of the Lower Tennessee Valley, ” was written under Christopher Lasch at the University of Rochester. Moore’s father, Robert Leslie Moore, was forced to sell his farmland in “Big Bottom,” near Hustburg, Tennessee, to TVA in 1942.