Whatever Happened to Southern Democrats

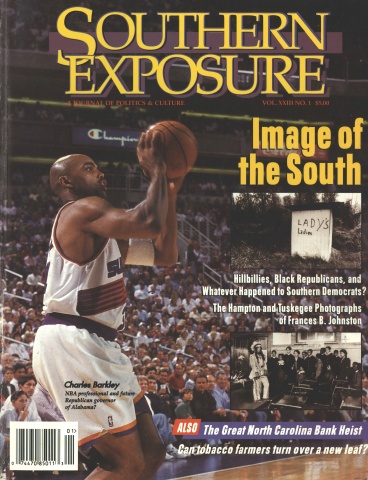

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Following the 1994 election, Southern Democrats have become as rare as the old blue laws in the South, and Republicans have become as numerous — and twice as aggressive — as the strip malls on the edge of every Southern town. Will the South become a new Republican stronghold?

The election of 1994 continued the long march of the Republican Party for control of the Southern political scene. Employing a strategy which capitalized on the growing anxieties of the middle class and generated a veiled appeal to racism, Republicans swept far into the region, making inroads not only in the Deep South, but in more moderate border states as well. Throughout the region, voting patterns were nearly the same: White men and women fled the Democratic Party. According to VNS, a consortium of media outlets that conducted exit polling on election day, 69 percent of Southern white males and 61 percent of white Southern women voted Republican in Congressional races. Nationwide, the figure was 57 percent of white males voting for the GOP.

While African Americans continued to vote predominantly Democratic, low African-American voter turnouts made it impossible for many white Democratic candidates to withstand the Republican onslaught. Reapportionment and its consolidation of minority Congressional districts may also have left Democratic incumbents without the necessary minority margins to overcome the desertion of whites to the Republican Party.

Two schools of thought have emerged to account for Southern voting patterns in 1994. One holds that November 8 marked the final shift in a realignment begun with the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts of the mid-1960s. A second views Republican inroads as the result of Southern dissatisfaction with the administration of President Bill Clinton and the stitching together of various disaffected special interest groups. While the answer may be somewhere in the middle, it is clear that the South, long a bastion of strength for the Democratic Party, has become an uncertain ground.

While Democrats still hold the majority of Congressional seats in the South, and 10 of 11 state legislatures, trends over the last 30 years show the middle class white voter slipping steadily away to the GOP. Southern Republicans gained three governorships, three U.S. Senate seats (including the defection by Alabama Senator Richard Shelby to the GOP), 16 House seats, and control of the North Carolina statehouse and Florida Senate. Republicans now hold 13 of 22 Senate seats, 64 of 188 House seats, and six of the 11 governorships.

By all accounts the November election was a nightmare for Southern Democrats. In spite of a generally robust economy, falling deficits and the advantages of incumbency, Democrats were unable to overcome a public disenchanted with government at nearly all levels. By the time the polls closed, voters had turned out many veteran Democrats and captured most of the open seats. For the first time in 40 years, the Republicans were in control of both houses of Congress.

How Everyone Changed Sides

In the post-Civil War South, clear lines were drawn between African Americans, who were predominantly Republican (the party of Abraham Lincoln), and the whites who composed the Democratic Party. It was not until the Great Depression, when Franklin D. Roosevelt offered the country a New Deal that these old lines were crossed and new ones drawn. Many African Americans, particularly in the North, joined the Democratic party in support of Roosevelt’s administration. They joined in sufficient numbers to influence white Democrats in the North and gain their consideration in policy making. This initial shift prompted a more sweeping realignment in the South when Southern white Democrats reacted to the desegregation of their party with the Dixiecrat movement of the 1948 Democratic National Convention. Disaffected Southern Democrats nominated South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond and Governor Fielding Wright of Mississippi as State’s Rights candidates for the election against Harry Truman.

Thurmond, who switched to the Republican Party in 1964 (and now chairs the Senate Armed Services Committee in Congress) said, when accepting the State’s Rights nomination: “There are not enough laws on the books of the nation, nor can there be enough laws, to break down segregation in the South.”

Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, approved under the Johnson Administration, reinvigorated Southern white support for the Republican Party. Despite a brief Republican appeal to African Americans with Eisenhower’s enforcement of the Brown vs. Board of Education decision in 1957, these two pieces of legislation also marked the end of African-American support for the Republican Party. In the 1960 presidential race, Republican Richard Nixon had received some 40 percent of the African-American vote. By 1964, with the candidacy of Barry Goldwater and the abandonment of the Civil Rights issue by Republicans, African Americans had fled the GOP.

In 1968, Nixon and Independent George Wallace, the Alabama governor who was a flamboyant segregationist, split the South. Wallace captured all the Deep South states. In 1972, Nixon swept the entire South, and in 1976 even the presence of Georgian Jimmy Carter on the ballet could not bring white Southern voters back into the fold of Democratic politics. Carter received only 46 percent of the Southern white vote.

In 1980, conservative Republican Ronald Reagan swept all the Southern states except Georgia. The 1980 election also gave Republicans control of the United States Senate, which they held until 1986. The Reagan years marked a new Republican sophistication in regard to attracting the white Southern voter. The president attacked the programs of the New Deal and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, and packaged cuts as a reduction of federal intervention. Attacks on federal programs for the poor and inner cities provided a new lexicon which, on the surface, had nothing to do with race. At a time when “white flight” from the cities to the suburbs was in full stampede, due in part to the problems of urban crime and a perceived decline in educational standards, this provided uneasy whites with convenient code words to define issues of race, without seeming to be talking about race at all.

Then There’s Tradition

While Southern Democrats have been moving away from their party on national tickets, they have generally stayed the course on local and state races. Democrats still control the statehouses and many of the Congressional House and Senate delegations in the South. Race explains in part the phenomenon of national realignment but it does not account for continued Democratic control of the statehouse and the courthouse. The explanation lies deeply rooted in tradition, class, and economics.

In what is considered the seminal book on Southern politics, Southern Politics in State and Nation, V.O. Key described tradition as a powerful force in influencing voting patterns, especially in the South:

“Although the great issues of national politics are potent instruments for the formation of divisions among voters, they meet their match in the inertia of traditional partisan attachments formed generations ago. Present partisan affiliations tend to be as much the fortuitous result of events long past as the product of cool calculation of interest in party policies of today.”

One example would be the Appalachian regions of upper east Tennessee, western North Carolina, and southeastern Virginia. Because of the relatively low number of minorities and their anti-secessionist sentiments in the Civil War, these regions have remained generally Republican for more than 130 years.

In east Tennessee, Republicans have held Congressional seats almost continuously since the Civil War. In races beyond their immediate vicinity, though, these voters can be swayed. In 1986 and ’88, they helped to elect a Democratic governor, and Democratic U.S. senators in ’82, ’84, ’88, and ’90. In the 1994 election, east Tennessee Republicans returned to their GOP roots. Increased anxiety over economic concerns, the growth and organizational power of the religious right, and the all-out campaigns of special interest groups like the National Rifle Association and the health care industry contributed to the Republican tidal wave. Most observers agree that race was not much of an issue in this Republican stronghold. It was a renewed enthusiasm for the GOP and a general dissatisfaction with Bill Clinton that brought home the faithful.

Nicked by the Double-Edged Sword

After waiting 40 years to regain control of Congress, Republicans now find themselves saddled with promises to keep: term limits, massive tax cuts, reduced federal spending, and a balanced budget. Should they succeed, the newly minted Republican voters of the South may become seriously disenchanted. With its long history of sending politicians to Washington for a lifetime, and with the seniority system providing Congressional elders with the power to direct federal spending toward home, the South has been a particular beneficiary of federal largess.

The Wall Street Journal, in a December story about Limestone County, Texas, provides just one example: The county’s nearly 21,000 residents paid about $21 million in federal taxes in 1991. The county received back some $85 million in federal expenditures, a return of more than 400 percent. The figure included some $41 million in Social Security and other federal retirement benefits, several million dollars for the school systems in the county, and $2.6 million in food stamps, agriculture funds, and Medicare and Medicaid monies. In addition, the county received about $25 million in 1994 to operate a state school for the mentally retarded.

The Journal wrote, “So important has such federal money become to Limestone County that its residents now instinctively turn to the government for help — and expect to get it. ‘If you think people are angry now,’ says Ray Carter, a retailer and . . . an official of the Mexia Lion’s Club, ‘just wait until you see what happens when they try to cut off some of these programs.’”

The South is full of Limestone counties that have benefited from expenditures from the energy and agricultural departments, Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. Region-specific programs add more federal benefits. The Tennessee Valley Authority, created in the New Deal, provides cheap public power to millions and employment to thousands in the Tennessee Valley states. The TVA has long been eyed by Republicans for budget cuts or even privatization. The Appalachian Regional Commission, organized in 1965, has built nearly 3,000 miles of roads and spent millions of dollars on infrastructure, education, and health improvements in the eastern mountains. ARC has been another favorite target of Republicans.

The presence of the federal government in everyday life will become ever more clear as Congress and the Administration vie to accelerate budget cuts. In a December 6, 1994, poll conducted by the New York Times and CBS, 81 percent of Americans favored a balanced budget amendment. However, if a balanced budget meant more federal taxes, support fell to 41 percent. If balancing the budget meant cutting Social Security, support dropped to 30 percent. If cuts in Medicare were required, only 27 percent favored the amendment. And only 22 would favor the amendment if it meant cutting federal education spending (a favorite Republican target).

An Abstract Mandate

If the November 8 election was a mandate for Republicans and the “Contract with America” — as they believe it was — they now risk public anger for delivering on what they promised. In the final analysis, Republican realignment in the South may be more influenced by the actions and policies of the new Congress in the next two years than by the historical foundation that has gradually bled the Southern Democratic Party of its strength. The key battleground appears to be the white middle class, and here Republicans will hold the advantage in that these voters have largely overcome (at least on a national level) the forces of tradition in their voting patterns.

While many observers agree that race was a key issue in the 1994 election, the Republican reluctance to directly discuss the issue and its place in their political strategy may reflect the GOP’s piqued interest in courting the white Southern vote. In The Two-Party South, Alexander Lamis notes a frank and revealing discussion in 1981 with a Reagan White House official who said:

“‘As to the whole Southern strategy that Harry Dent and others put together in 1968, opposition to the Voting Rights Act would have been a central part of keeping the South. Now [the new Southern strategy] doesn’t have to do that. All you have to do to keep the South is for Reagan to run in place on the issues he’s campaigned on since 1964 . . . and that’s fiscal conservatism, balancing the budget, cut taxes, you know, the whole cluster . . .’

“Questioner: ‘But the fact is, isn’t it, that Reagan does get to the Wallace voter and to the racist side of the Wallace voter by doing away with Legal Services, by cutting down on food stamps . . .?’

“Official: ‘You start out in 1954 by saying: “Nigger, nigger, nigger.” By 1968 you can’t say “nigger” — that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, state’s rights, and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, all the things you’re talking about are totally economic things and the by-product of them is that blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is a part of it. I’m not saying that. But I’m saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me — because obviously sitting around saying, “We want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing and a hell of a lot more abstract than “Nigger, nigger.”’”

The Republican refinement of the lexicon continued in 1994 with welfare reform, crime, and school vouchers replacing New Federalism, busing, and fiscal conservatism.

Realignment in the South?

To capitalize on the trend of Southern white flight from the Democratic Party, the GOP must devise the least painful method possible for delivering on its promises in the Contract. In an expanding economy, with healthy growth, the GOP may achieve success in its strategy of tax cuts and reduced government, so long as the voter can feel the impact on his or her personal finances.

There is a dark cloud on the horizon for Republicans, however. The Federal Reserve Board’s aggressive credit policies of 1994 lead many economists to predict a sharp drop in growth rates, starting as early as next year. With control of the Congress, Republicans will be without their traditional whipping post — the Democratic Congress — as they campaign to consolidate their gains in 1996.

For Democrats, the next two years will be spent in acclimating to the role of minority status, while at the same time redefining themselves in a way to bring back the white middle class without losing the liberal and minority wings of the party. It will be a daunting task. November 8 exposed deep cracks in the Democratic Party. Whether Clinton will be able to heal the rifts and assuage concerns about his viability in 1996 remains to be seen.

Both parties have tremendous challenges before them: the Republicans in translating a seductive philosophy into concrete policy without alienating their new constituency; the Democrats in devising and articulating a new platform that recognizes and addresses the current drift to the right without losing their liberal and minority base.

In the end, the party able to achieve its goals will be poised to either consolidate or return to power. While Republicans have been able to accelerate the realignment trends of the past 30 years, fundamental realignment has not taken place: Democrats still control most of the state legislatures. At the same time, Democrats can hardly afford to be indifferent to changing voting trends. Southern voters, particularly white voters, have broken with Key’s traditional voting attachments. Added to this new paradigm is a public demanding to see immediate results from their officials and their policies. Both parties need to move quickly and correctly to achieve their goals. What happens between now and the 1996 elections will determine whether there will be real realignment in the South.

Tags

D. Keith Miles

D. Keith Miles is a writer living in Nashville, Tennessee. A former political journalist, Miles served as press secretary from 1986 to 1994 for former Tennessee Senator Jim Sasser. (1995)