Revenge is Sweet

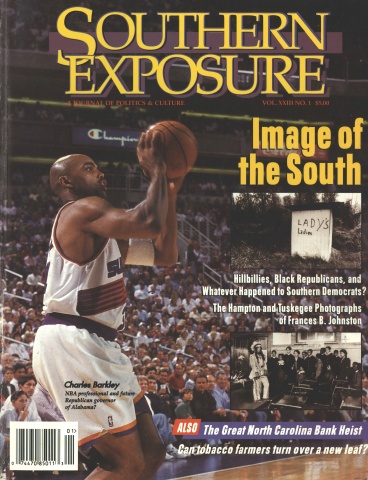

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

What follows is a baker’s dozen of little dilemmas taken from my experience as a writer/performer working out of a place that has strong stereotypes attached to it.

There are three general categories of stereotypes included here. One has to do with being female, one has to do with being an artist, one has to do with being Appalachian. They are not so pure as that — nothing in this business is ever pure — but if you care to make recipes, these are the basic ingredients.

I have stated these dilemmas with what I hope are enough details to give the picture; I have not gone into what I did in the next moment with any of them. There is a reason for the omission. In the psychology of learning, there is a phenomenon called the Zeigarnik Effect. The basic idea is that within a situation or a story, it is human nature to seek a resolution, and if one is not provided, the individual will seek his or her own resolution and remember the experience better for it. Have at it.

1. You write a series of monologues and dialogues from people you have met in the region, and you stay as close to the bone as you can, but some of them are funny, and you play them all over this country and on the radio, and you become something of an exotic because the region gets fashionable in the arts and funding communities, and you sound like you are from it, and people laugh, and you wonder, standing in front of an audience in Washington or Los Angeles, whether they are laughing at you or with you, because the line is a fine one, and the problem with a moment’s truth of the sort you can capture in a monologue is that it sometimes lends itself to stereotype whether you had it in mind or not. You wonder sometimes if you are feeding the stereotype instead of combating it. So you . . .

2. A young woman accosts you outside the stage door after a performance of the monologue/dialogue material in Atlanta, Georgia, and she is furious because she is convinced you have been to east Texas and stolen stories, she is sure one of the pieces is from her great aunt and uncle from east Texas, and that you just say you are from east Tennessee because “Appalachia is a much more fashionable place to be from.” The piece in question is from your aunt and uncle, who never in their lives left east Tennessee.

3. In a regional magazine, you read that you are from California and have moved to Appalachia and have been collecting stories that obviously take an outsider’s ear to hear. Someone who was from here couldn’t do it. You are very surprised by this, you are from here, or you were, last time you checked. You’re pretty sure you’re not from California.

4. Other people begin to perform the material, and you have the misfortune to see one actor with a tooth blacked out, in overalls, spitting fake tobacco amber, standing in front of a stage barn door, doing a piece so wrong it makes you cry. The whole production is like that. And you are supposed to speak to the actors and director after it is over. When you meet them, they want to know how you liked it. You say . . .

5. When the book, Stories I Ain’t Told Nobody Yet (a collection of performance material), is published, the cover comes with a shack on the side of a mountain with the porch turned to the hill and not even to the view, and you throw a fit, you will not have this stereotype on the front of a book you’ve taken pains to make sure helps combat the regional stereotypes. And the publisher agrees to spend the money for a second run on the cover and sends the work back to the artist who causes a bush to grow over the cabin, and you are happier. When you meet the artist, he had represented his grandfather’s home.

6. When the book is finally out, you get letters from students who inform you that the “ain’t” in the title is not proper English and that most of your characters in the book don’t seem to know proper English, and didn’t they go to school? What’s wrong with them? What’s wrong with you? Don’t you know proper English either? You write them back, you say . . .

7. You do a reading as a favor for a teacher in a local high school. You feel it is important to show up in local schools, because you are from here and the books have your name on them, and your very presence is a sort of permission for students to dream of these things for themselves. So you take the time and do it free. You finish the reading and the teacher says, “It’s all right for Ms. Carson to sound like she does, but none of us want to sound like that, now do we?” You say . . .

8. You are refused payment for a performance you drove 150 miles to do at a Christian school in North Georgia because you “profaned the chapel with laughter.” You can think of several more profane things than laughter, some of which you can imagine yourself doing, but instead you . . .

9. You write a play, Daytrips. It is autobiographical and hard stuff about duty and madness. You are told repeatedly it will be more universal if you set it somewhere besides Appalachia, and if you want it to sell, you need to do that.

10. The play is three weeks into rehearsal for its first professional production (in Los Angeles), and you are in a producer’s meeting and the producer finally turns to you and says, “It (the play) is not dark enough yet, the South is a dark and terrible place, I know James Dickey, I saw Deliverance.” You want to crawl across her desk and prove that the South is a dark and terrible place, Dickey or no Dickey, but you don’t, you say. . .

11. A Northern city. You sit through hours of rehearsal at a major theater in which a speech coach is trying to teach the actors an “Appalachian accent” to use in the play. It sounds to your ears like a combination of Scarlett O’Hara and Sut Lovingood, and terribly fake. You finally say that the rhythm of delivery is much more important to you than accent, and that people could probably pick up enough of that to make it work by listening to you. The speech teacher, who has never been to Johnson City, or to the mountains for that matter, says, “Oh, no, dear, your speech is not authentic.”

12. You are to receive a substantial award for the play, and a reading is being rehearsed for the occasion. The director keeps calling you asking for line changes for one character. Finally, you go to the Northern city early, and the rehearsal is a wreck because he has cast a vaudeville sort of comedian who, with his encouragement, bounces in her seat to show agitation, delivers every line as a punch line, and mugs till she gets a laugh. This is for the hardest, most ironic role in the play. It doesn’t work. You try to explain that the comedy of the role only works if it is ironic, the character cannot find herself funny, she is dead serious in what she says and does, it is the circumstance that makes a given moment comedic. He tells you to shut up. He says, “Women playwrights never know what they’ve written, and if you’d just change a few lines, you’d have a decent play.” You want to say a change in testosterone levels might help more than a change in lines, but you don’t. Instead you . . .

13. You publish a collection of short stories, The Last Of the Waltz Across Texas, and, in keeping with what you seem to be able to make work as a writer, they are set in this place and they are hard/ironic and comic, but they are as real as you can make them and still make short stories, and during questions and answers after a reading with about two hundred people in the audience, a student stands up to tell you he thinks you’ve done a lot of damage with this book, that it’s all stereotype, and if you’re so concerned about that, how could you publish it? You want to throw up but you don’t. You say . . .

Enough. Listing this stuff just makes me mad all over again. I always said something in the moment, but hindsight means that now, I have better things to say, and I spend time saying these better things to nobody, to the view out my window, than I do writing the situations.

This is by no means all of the situations I’ve run into, this is a selection from several years. I should add that moments like these are not all that common, or I wouldn’t do performances or readings or show up in public as a writer. I’d probably still write. You risk yourself as an artist when you publish, even more when you stand up as a performer or speaker, and if someone, through prejudice or ignorance, or whatever else, did this every time I showed up in public, I’d not be near so inclined to do it. On the other hand, I’ve grown a thicker skin and a sharper tongue than I used to have — in part, for these experiences — and I might do it now for the fun. And revenge — well, I tell these stories for revenge and revenge is sweet.

One more note: The young woman who thought I’d been to east Texas and stolen stories paid me a tremendous, if backhanded, compliment. And what I learned from that moment is that the closer I can get to the specific eccentricities of a real human being with a real place in the work I do, the more universal the work becomes. That was a gift, though in the moment, it felt a lot like the slap she delivered. Similar stuff is true of several of these moments. Sometimes it takes a confrontation for me to learn anything, and these have all been, to say the least, learning experiences.

Tags

Jo Carson

Poet, playwright, and author Jo Carson is Southern Exposure’s fiction editor. (1995)